THELMA GOLDEN ON ARCHITECTURE AND ART

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

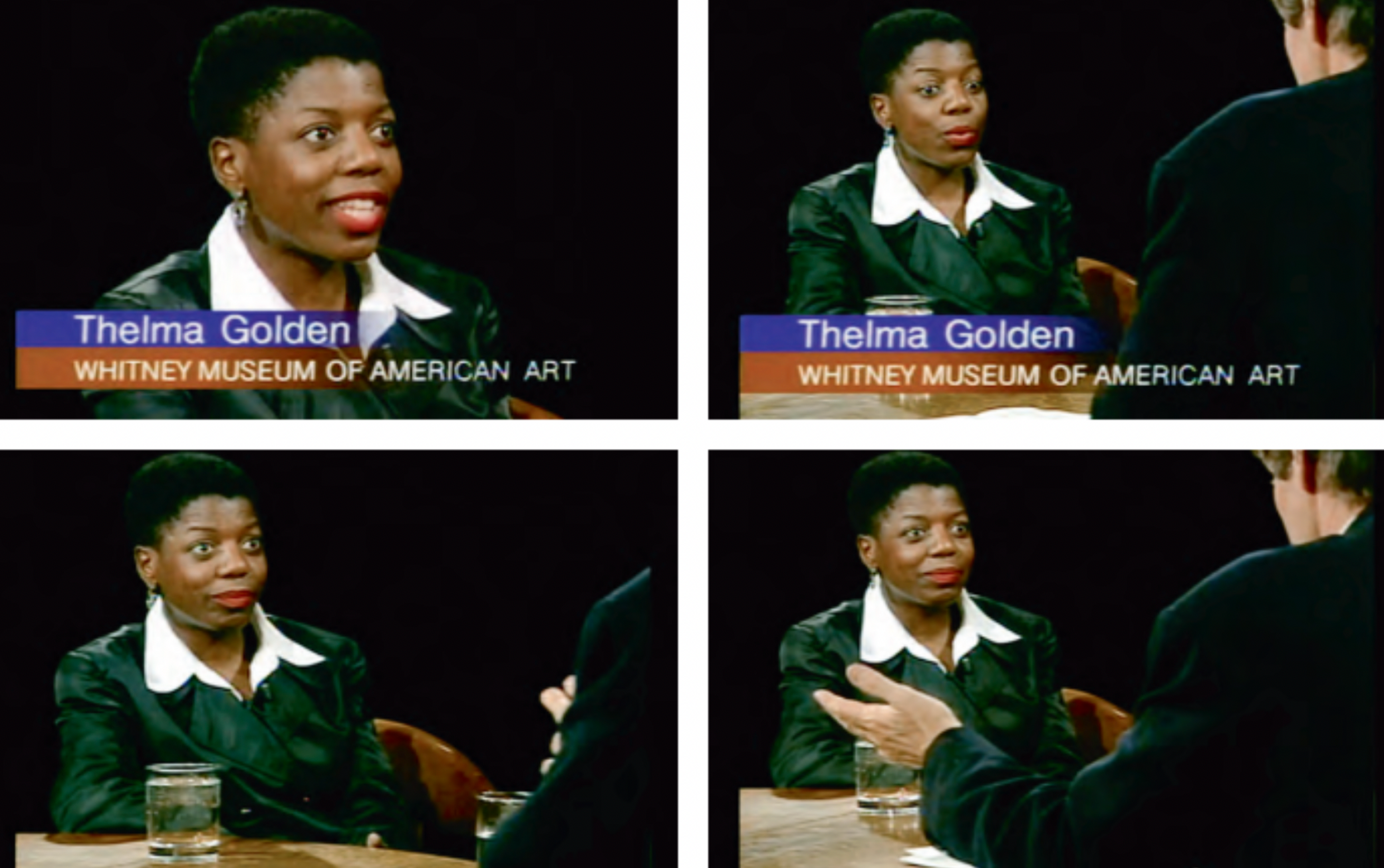

Thelma Golden interviewed on Charlie Rose in 1995 to discuss Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art.

In 1994, when Thelma Golden was 29 years old and working at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, she curated Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art. It was a seminal group exhibition that set forth a complicated understanding of the Black body, working through ideas on how visual production creates Black masculinity. She describes Black Male as a show she both keeps making and can never approach again. The year before, she had co-curated the 1993 Whitney Biennial, whose exploration of ideas around race, gender, and sexuality continues to reverberate in contemporary debates about identity politics. They also inform my own thinking on how art circulates ideas of Blackness and how I move through the world. Since 2005, Golden has been director and chief curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, an institution that, since its founding in 1968, has been a nexus for artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally, and for work that has been inspired and influenced by Black culture. An art museum, Black Museum, Harlem institution, and cultural space all at once, the Studio Museum is in a transitional period right now: the West 125th Street building it occupied since 1982 has been demolished, and is being replaced by a bigger, purpose-built home designed by Sir David Adjaye. Golden, whose influence extends far beyond the art world — she served on the Committee for the Preservation of the White House from 2010 to 2016 —, oversaw the process of getting this new building designed, funded, and erected. When it opens in 2024, it will continue to helm the rich curatorial conversations and generous community building that make the Studio Museum such a unique place.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What is your relationship to architecture?

Thelma Golden: My relationship to architecture is defined by my relationship to art. My sense of consciousness around architecture as a physical, intellectual, even metaphysical space comes from my engagement with art in spaces. Growing up in New York City, I was conscious of the built environment, and my sense of the specificity of architecture as a discipline came through visiting different types of museum and gallery spaces, from the model of the castle, to the Modernist structure, to the white cube, to the adaptive reuse of space that so many arts organizations occupy, among them the Studio Museum in Harlem. My sense of built space informed how I think about the ways curating can enable people to engage with art and objects.

As a native New Yorker, you encountered architecture across the spectrum in terms of scale and style. How did it feel to leave for the more rural suburbs surrounding Smith College?

By the time I went to college, I understood the symbolism of architecture. The truth is, I wanted to stay in New York, but my parents believed my college education needed to be both academic and cultural. For them, my attending the school campus, with its historic and picturesque buildings, represented the prototypical New England liberal-arts education. I will say, I made a conscious choice to live in the one Modernist dorm at Smith in the late 1980s, Ziskind, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1955, because it was an anomaly on the campus. Cutter House [also by SOM, 1957] and Ziskind House represented this insertion, this intervention, into that campus which, for me, was related to what I desired from art history and African American studies.

Is that something you felt like you had to cultivate? What did those choices mean to you in terms of your ideas around identity?

I studied art history because I wanted to be a curator. In my second year at Smith, I interned at the Studio Museum, which radicalized my academic trajectory: I came to understand the importance of an institution and its work in expanding the art-historical canon. I went back to Smith with a wider lens on how to think about American art, contemporary art, and the history of art more generally.

Thelma Golden interviewed on Charlie Rose in 1995 to discuss Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art.

Right. It becomes a question of how do you curate Blackness? Because there’s Blackness inside of the institution (Black employees), Blackness as institution (Black senior staff), and how the institution and the canon understand Blackness as a form (art). Did African American studies inform how you complicated that narrative?

Yes. I pursued the African American studies double major because it allowed me to situate my investment in art history into this larger dialogue in the humanities as it’s related to Black art and culture. African American studies gave me this wider platform to think in, about, and through these issues and other disciplinary models, which became a rich way to enter into thinking about contemporary art.

In an interview with Glenn Ligon via Betsy Sussler in BOMB magazine you talked about how curating was also a social practice, how it is about listening to what people are paying attention to. How does listening inform your practice?

In that particular interview, I was referring to the fact that there are many different ways to gather information. One kind of curatorial practice does require hundreds of studio visits. And while I did that as a curator, and continue to do so to some degree as a director, I realized my information gathering expands when studio visits aren’t my only strategy. In that conversation, I was pointing to what’s been an essential part of my relationship with Glenn, as it is with so many artists, but perhaps with Glenn most singularly, which is an ongoing dialogue about art. All the approaches I might take into subject, idea, artist, but also how I think about the space of exhibitions.

The Studio Museum is an aggregator and so many people have passed through it as a cultural institution. I’m curious what your relationship to mentorship is, both in how you provide that to others and where you find it for yourself.

I was beautifully supported in my career as a young curator. I feel like this is directly responsible for why I’ve been able to walk through the art world, the museum world, and do the work I do. One can imagine that the work of a curator is understood through what ends up on the wall as an exhibition or collection or presentation. But I have seen my curatorial practice include work that isn’t just about what exists in public — it’s also about how I exist in community, in conversation, and in collaboration with artists, as well as with other curators. The word mentorship might be one way to talk about it, but I see it as a more complex, reciprocal relationship. The majority of my career has taken place in two institutions: the Whitney and the Studio Museum in Harlem. My involvement centers around Black art, Black artists, and Black culture. It is a super-wide breadth within a relatively contained context, which means many people who exist in my work life also exist in my personal life.

While you were at the Whitney, what did it mean to you as a practicing institution?

My time at the Whitney was incredibly important to my formation as a curator and a thinker, not only because it was the place where I most specifically and most purely curated and became an exhibition maker, but also because it significantly informed my idea of institutions — one that I could integrate into and also interrogate. That interrogation of thinking about the museum, cultural specificity, how it defined my work there, provided me with the basic questions I continue to ask in my work at the Studio Museum.

What was the architecture and programming of the Studio Museum when you first encountered it?

I first encountered the Studio Museum’s architecture as a child. My father was born and raised in Harlem, my mother in Brooklyn, and I was born and raised in Queens after they married. My parents remained connected to the cultural institutions of Harlem and Bed-Stuy, where my mother was from. I first knew of the Studio Museum at the original second-floor loft space on Fifth Avenue between 125th and 126th Streets. When I was an intern, I came to the building at 144 West 125th Street, where I began to understand how the museum was part of the wider community. I also began to understand the concept of adaptive reuse. Generations of staff acknowledged that the building at 144 West 125th Street had not been built as a museum, but, through decades of brilliant work, they imbued that space with all of the best qualities of a museum. For many people, it was the first or only time they experienced that kind of architecture. When I came back as director, I had a deep familiarity and love for the building, having experienced it in such a formative way earlier in my career. At that time, the museum didn’t have a theater, so everything happened in the gallery. That made me think about the space and its idiosyncratic floor plan, one that only had one wall higher than 10 feet. It was a space that could not necessarily be broken up into rooms, and which allowed visitors to see what was happening on the first-floor level from the mezzanine and vice versa. It had a deep openness to it, a fluidity. As a curator, I had to think about how to maximize making exhibitions in that kind of context. J. Max Bond Jr., the architect who adapted the 125th Street building, recognized that. He created the opportunity for us to do the work of a museum without the codes. It wasn’t quite a cube, nor was it a castle-temple model either.

Now that you’re rebuilding the Studio Museum, what’s the future?

As a curator, I see myself as the link between the Studio Museum’s various buildings over the years. Previous directors spent an inordinate amount of time, effort, and energy renovating in waves to keep the 144 West 125th Street building — which dated to 1914 — running, safe, and operable. Reimagining our space led to an iterative process to get to an architectural brief that would determine what our future could be. That’s what led us to select David Adjaye to design a new building for the Studio Museum. His proposal responds to the real, practical, and pragmatic needs of a 21st-century museum, but also to the more profound and poetic ideals of what it means to be creating Black space in a Black metropolis defined through the sensibility of a global Black lived experience.

You’re partnering with MoMA while the construction of the new building is ongoing. I was thinking about MoMA and Studio as individual projects, and the parallels are undeniable in terms of their evolution as institutions in and of New York. MoMA was tasked with taking on architecture and contemporary politics of art, and Studio with taking on the social politics of space, body, temperament, and time. They are almost parallel mirroring institutions.

Yes. The partnership came about as a result of us closing in 2018 so that we could undertake building David Adjaye’s purpose-built museum. Because the new building will be occupying the exact same site, we were required to move out — not just the team, but also the museum’s archive and over 30 years of life. That forced us to think about how we would continue engaging our audiences here in the city, and the partnership with MoMA became a way to do that. There was a lot of precedent for the collaboration because some of our founders were involved board members, junior committee members, and staff members at MoMA. Our thinking about our past and histories came from many deeply thoughtful meetings and points of entry, but we complicated the narrative of how we would embed ourselves at MoMA and MoMA PS1 with exhibitions. Though the initial idea of partnership was to allow us to continue to work while we’re closed, it is one that, for us, will continue to exist even when we open our new building.

Let’s pivot to curating. I regularly think about the Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art group exhibition that you curated at the Whitney in 1994. For a show to feature artists of varying descent engaging in the politics and perception of what it means to be Black and male ruffled so many feathers. In terms of complicating the narrative of “the body”: I think that you actually brought language to a form that didn’t yet exist. It’s recognizable now, though it’s no longer billed as institutional critique in the way it once was, because of how institutions have become so self-aware, anxious even in how they proactively pose questions about their implication in staging or engaging in some kind of social politics. How do you make space for the conversations you felt you didn’t have access to when you were in a junior position at the Studio Museum?

Curatorial practice is the best way for institutions to accommodate multiple modes of presentation at once. I hope we’re providing the space for the widest potential, because I don’t think there can be just one conversation at the Studio Museum. We’re creating a space for curatorial opportunity so that we have curators of different generations working on the same exhibition, which brings about different approaches to what it means to put objects into physical space for an audience to encounter and engage with.

The Studio Museum is itself a complete architecture in that it provides artists with a context to display their work, artists in residence a platform and community to engage in conversation about their work, and fosters curators and museum staff who can then go on imparting knowledge acquired by the institution in their practice elsewhere.

Yes, you’ve said it. It’s this potent combination of cultural specificity, site specificity, site suggestiveness, and also a kind of institutional sensitivity

[Laughs.] It’s a mapping of culture onto site; we’re bent into this infinite loop.

I embrace all the definitions of us: art museum, Black museum, Harlem institution, and cultural space.