Emmanuel Olunkwa: What does architecture mean to you?

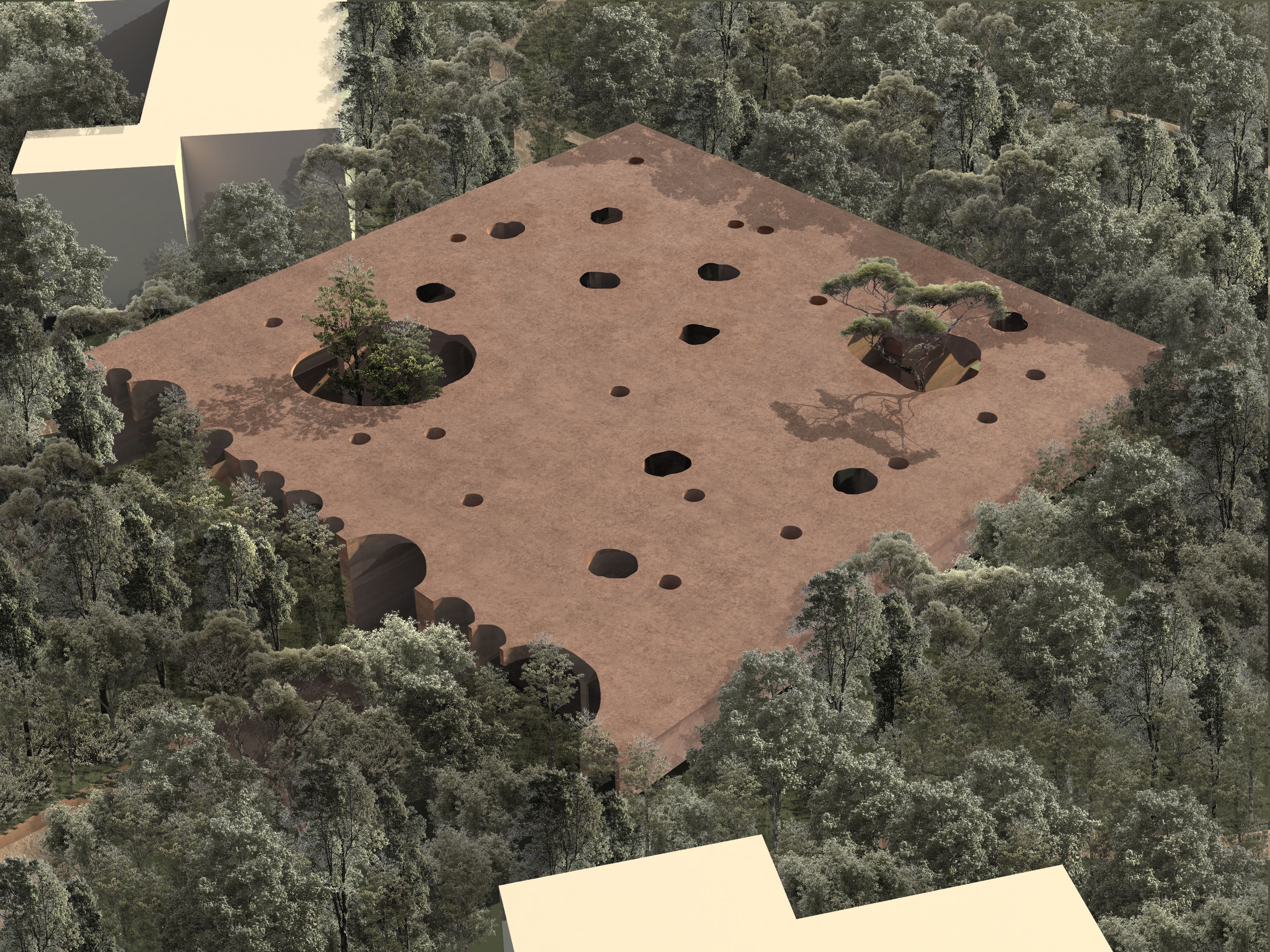

Sumayya Vally: I’ve always thought that architecture is about the physical makeup of space and bringing people together. The way we gather in a space depends not only on its basic physical attributes but also on ritual and atmosphere, and on forms of dress and decoration. Architecture is the manifestation of all forms of culture, a solidification of these rituals. If we look at all the spaces we have, they represent something ideologically. Think, for example, about how a body of people convenes in a lecture hall: there is a certain hierarchy present, with one person speaking on a stage and an audience sitting and listening. This arrangement comes from a set of ideologies, rituals, and belief systems that go back to ancient Rome and beyond, and it’s something we don’t actively question. We tend to accept architecture as a kind of background status quo. In terms of system building and networks of making, jewelry, sculpture, fashion, and music are also a kind of architecture unto themselves and have the potential to resonate within the infrastructure of architecture itself by injecting magic into it. This is why everyday objects and design have always influenced the work I make.

Where does your skepticism come from?

I don’t know that in the beginning it felt critical, but I think I had these instincts around what I saw in Johannesburg. I’m really interested in the city’s smallest mythologies, and was attracted to thinking about how these ideas and curiosities translate into form. There’s this story — in fact it’s scientifically true — that Johannesburg sunsets are extremely iridescent because of all the dust in the air from our mining history, a lot of which is toxic because it contains uranium. This extraordinary quality of light inspired a project I worked on which translates those colors into an installation. There were many early projects where I was really working with the histories and ecologies of the city, such as informal trade systems, ceremonies in traditional healing markets, church rituals, and jazz sounds, which were all direct manifestations of what I was experiencing daily. I didn’t think about them as critical at all or in opposition to an idea of architecture, I was just following an instinct about how much the city has to give to architectural practice, a line of cultures and influences that I now see has greatly nourished my practice.

You’ve spoken about how we all inherit different definitions of language. What are the circumstances of the world that we have inherited?

We’ve been handed down things from an extremely warped place. Architecture is so incredibly abstract that we don’t question what we have inherited, and we perpetuate the ideologies that surround us. On a baseline level, this world we’re living in is completely twisted in that it is full of colonial constructs. The nine-to-five workday is a capitalist system that, as we know, doesn’t take into account the rhythms of a woman’s body or any of the mythologies that come from different belief systems. It’s something you can particularly feel in South Africa.

What's happening there politically? Do you feel it aligns with what’s urgent in architecture?

We’re having a lot of conversations in South Africa about race, gender, the future of art, and cultural typologies. It feels much more relevant there than discussing those things in the global north. I think that the reason architecture in South Africa is less progressive than fashion, music, art, and other creative realms, the reason it’s still incredibly slow, white, and stuck in a colonial apartheid system, is because it requires so many resources and so much effort, and is therefore a much bigger ship to turn around. You need an entire infrastructure to make a building: a full suite of staff, hardware, and software, as well as a patron who has enough money and is willing to gamble on your work as an individual.