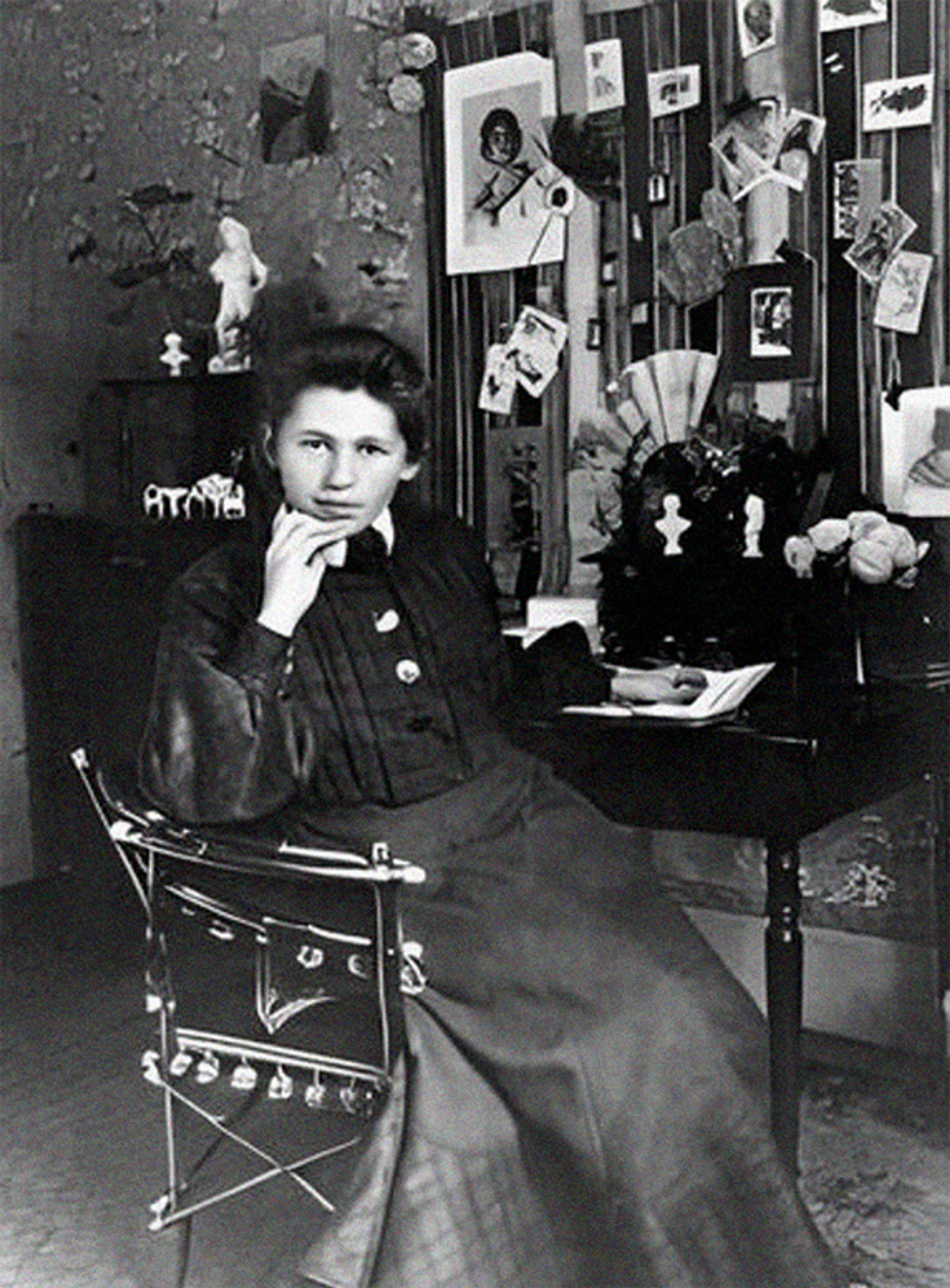

Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Photo by Okänd fotograf via Wikimedia Commons.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp's marionettes displayed at the Tate Modern Sophie Taeuber-Arp exhibition. Photo by london road via Wikimedia Commons.

The essence of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s (1889–1943) work has sometimes been described as joyous abstraction. The Swiss-French multi-hyphenate engaged with a plethora of ways of making; she slid fluidly between architect, teacher, painter, sculptor, dancer, writer, magazine editor, and designer of textiles, beadwork, costumes, furniture, and interiors. Her inventive visual language knit everything together in rhythmic harmony, transcending traditional boundaries between craft, design, applied and fine arts, abolishing hierarchies between prevailing notions of high and low. Her expressive performances were as salient as her design for the transformation and renovation of a cultural center in Strasbourg, the Café de l’Aubette, which was later labeled by the Nazis as so-called Entartete Kunst (“degenerate art”) and destroyed. And her extraordinary Dada Heads, the incisively witty wooden hat stand portraits adorned with colorful geometric patterns were just as important as her embroideries about which she wrote in her 1922 “Remarks on Instruction in Ornamental Design”: “In our complicated times, I have frequently asked myself why do we do such embroideries at all when there are so many more practical and especially more necessary things to do. I believe the urge to make things more beautiful is a deep and primeval one. Only when we go into ourselves and attempt to be entirely true to ourselves will we succeed in making things of value, living things [...].” Taeuber-Arp acted on this primeval urge. Moreover, under the violent shadow of early 20th-century Europe, in the face of two world wars, she challenged evil and injustice at her nearest source, herself. In awful, hard times, she made things alive with hope.

In the midst of World War I, Taeuber-Arp was a pioneering Dadaist figure. She and her subversive peers resented the vast bloodshed, questioning a culture capable of creating something like a World War. The Dada movement set out to dismantle standard ideas about art and life by embracing punk-ish nonsense and irrationality, challenging the stale aesthetic norms and unchecked materialistic and nationalistic values they believed had led to brutal horror. Responding to the era’s carnage, raucous Dada turned to the imagination and the absurd; in this way, the group declared war on war.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Photo by Eduard Wasow via Wikimedia Commons.

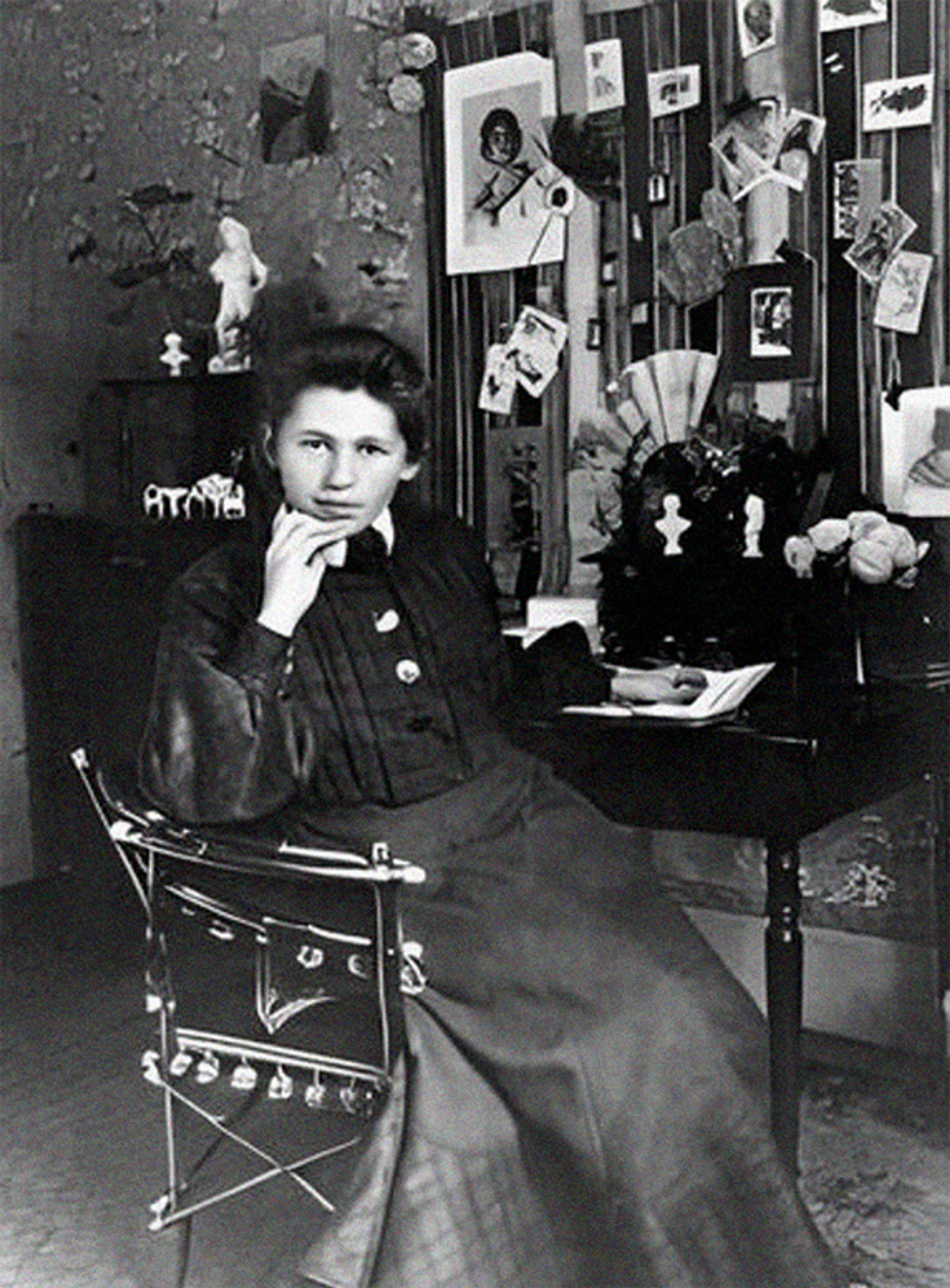

But unlike the more somber work of her Dadaist peers, Taeuber-Arp made joy a distinct motif. Led by her most generative formal device, the grid, colors and forms make allusions to the earth, the sea, and the sky in her experimental, egalitarian, and vibrant artworks. Perhaps her most original contributions to the Dada movement are her puppets, specifically the ones she crafted for the 1918 Dadaist adaptation of the tragicomedy, “König Hirsch” (The Stag King). Her wooden Stag King puppets were turned on a lathe, made up of playful but controlled geometric forms, with ligneous bodies decorated in wild and glorious colors. Crafting the puppets in the harsh milieu of WWI might seem at odds with the despair of the times, but what if her wooden marionettes were made animated and sentient, like Pinocchio? What might they report on her resistance to joylessness? Would the soul-containing puppets muse that answers might be excavated by investigating the way she lived?

Sophie Taeuber was born in Davos, Switzerland at the cusp of the 20th century. She studied at a Swiss trade school before attending an experimental applied arts workshop in Munich, and then the Hamburg Applied Arts School, which promoted the coextensive nature of art, craft and design. At the outbreak of World War I, she moved to Zürich, where she continued her studies in textile design and modern dance. The neutral city became a hotbed for a pacifistic avant-garde, with artists including Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball sheltering alongside Taeuber. Within it, Taeuber plunged into Modernism and made a trailblazing breakthrough towards abstraction.

Before long, Zürich’s School of Applied Arts appointed her professor, where she ran the textile department. She taught by day and performed by night under the moniker of “G. Thauber” at Dadaism’s headquarters, Cabaret Voltaire; the pseudonym aimed to circumvent censure from unimaginatively conventional work colleagues. Hugo Ball, to whose poem “La Caravane” Taeuber-Arp once performed, wrote in his diary, “I saw in Sophie Taeuber a bird, a young lark, for example, lifting the sky as it took flight. The indescribable suppleness of her movements made you forget that her feet were keeping contact with the ground, all that remained was soaring and gliding [...].”

Within Zürich’s Dada crowd, she met her soul mate and frequent collaborator, Alsatian artist Hans (later known as Jean) Arp. The two married in 1922. Speaking of their work together in Arp on Arp: Poems, Essays, Memories (1972), Jean Arp wrote, “We humbly tried to approach the pure radiance of reality [...] We wanted our works to simplify and transmute the world and make it beautiful.” At the end of the 1920s, following the success of the design for the Café de l’Aubette, the couple settled on the outskirts of Paris in a studio-home that Taeuber-Arp designed, where her complete vision is maybe most palpable. The modernist house sits a short train ride from the center of the city in Clamart, at the edge of the Meudon forest, the textured, box-like building is cut with sleek, sharp-lined concrete entrances and balconies. Within it, aesthetics and functionality coalesce. Taeuber-Arp’s primeval urge to make the things she owned more beautiful is glaring. Sun bursts through the building’s angular shuttered windows. Warm light casts shadows decorating the floors and walls with luminous Taeuber-Arp-like geometry. Meandering through the house’s living quarters, studio spaces and garden, one detects a crackling vibrancy emanating from it all, even in the spirited, rough local burrstone of the walls. The building is haunted — positively — by Taeuber-Arp. It breathes with the energy she put into it.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Photo by Okänd fotograf via Wikimedia Commons.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Study for a Marionette, 1918. Sophie Taeuber-Arp, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

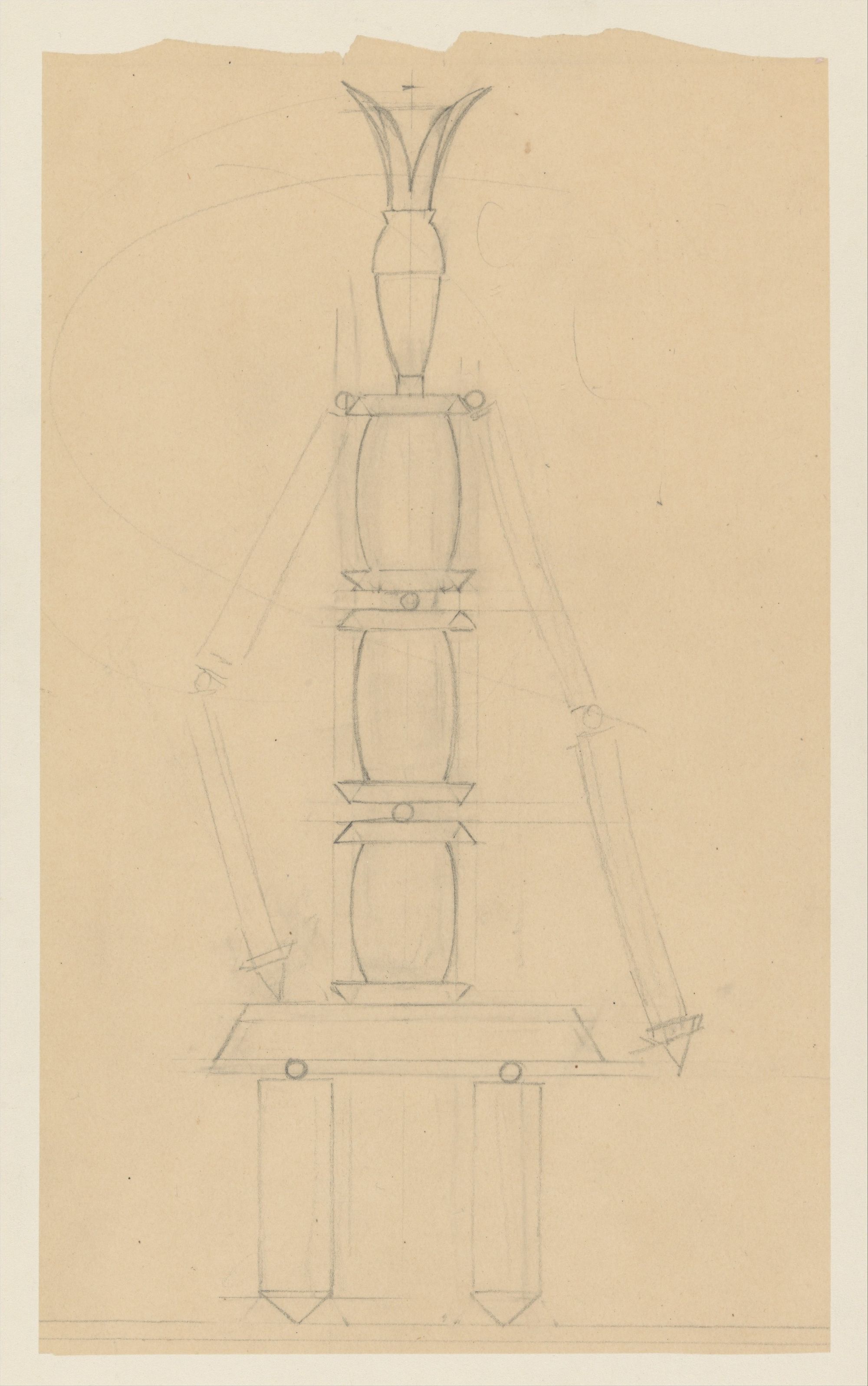

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Animated Circle Picture, 1935. Photo by Paradise Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons.

Moments of peace and renewed hope followed in the house she built for herself. Taeuber-Arp updated her business card to read “architect,” continued to teach, and started the art magazine Plastique. Its first issue was devoted to radical Kyiv-born artist, theorist and founder of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich. She also joined Paris-based artists’ groups that promoted abstraction like the short-lived Cercle et Carré, exhibiting alongside the likes of Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky. Her days were lush with experimentation, friendships, and collective joy.

In 1940, World War II crept up. The duo fled their Clamart dwelling days before Nazi Germany marched in. An isolating exile from German-occupied Paris followed. For Taeuber-Arp, this was a devoted time of prolific art-making made with unexacting, transportable materials, set against the backdrop of a dreadful new global conflict. The scores of drawings on paper she made while uprooted are lyrical. In the face of the chaos of war and her displacement, the ordered structure of her grid disappears. Lines planned with precision freely dance; gestural coiling elements interlace with straight, angular ones. Yet the vibrancy of her palette in the immensely productive time becomes somewhat muted, suggesting a phantom of anxiety lingering nearby, still her unflinching devotion to her vision remained. About this time, Jean Arp wrote, “Her inner clarity struck everyone who met her. She blossomed like a flower about to droop [...]. From her purity she drew the courage and confidence to endure the immense misfortune of France [...]. From the depths of the most intense suffering, blossoming spheres shoot forth [...]. Lost and impassioned, she drew lines, long curves, spirals, circles, roads that twist through dream and reality [...].”

Interior of the Fondation Arp. FondationArp, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Façade of the Fondation Arp. Sanchalex, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In time, the couple returned to Switzerland. Not long after, Taeuber-Arp missed the last tram and slept at friend and artist Max Bill’s house. Asphyxiated by emanations from a faulty stove, she died of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning at 53. Since then, despite being a spearheader of the interwar European avant-garde, her legacy has seen a wretched under-celebration. For years she slipped through cracks in the canon without due recognition. But things have begun to change, in part thanks to a comprehensive traveling retrospective first exhibited at Kunstmuseum Basel, and then Tate Modern and MoMA in 2021. Since then, a new interest in her life and work has begun to disentangle her from wrongful obscurity, and Taeuber-Arp’s studio-home exists today as the Foundation Arp, which is “dedicated to the dissemination and protection of its exceptional collection, as well as the promotion of the cultural heritage of Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber, in France and abroad.” Plans for the foundation were outlined by Jean Arp several years before his death, and his second wife, Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, initiated its creation in 1978. Visitors who pass through the property today immediately encounter her eternal joyfulness; the foundation website states that the historic site is “steeped in poetry and magic.” During her peace-containing time on the outskirts of Paris, Taeuber-Arp wrote to her goddaughter, “I think I have spoken enough to you about serious things; which is why I speak [now] of something to which I attribute great value, still too little appreciated — gaiety. It is gaiety, basically, that allows us to have no fear before the problems of life and to find a natural solution to them.” Is this unhinged optimism? Maybe. But within the turbulence of early 20th-century Europe, when the world was broken and rays of light were rare, she carved out hope. In days of tortured fear and suffering, rapturous creativity and joyous abstraction offered an alternative. Taeuber-Arp’s final drawings were vigorous pen and ink compositions possessed by what had become her best-loved shape, the circle. In a 1981 catalog essay, longstanding MoMA curator Carolyn Lanchner wrote that “for Taeuber, the circle was the cosmic metaphor, the form that contains all others.” After her death, Jean Arp wrote, “It was Sophie Taeuber who through the example of her clear work and her clear life showed me the right path, the road to beauty. In this world, up and down, light and darkness, eternity and ephemeralness are in perfect balance. And so the circle closed.” Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s enduring work was buttressed by an efflorescent resilience. Her fearless practice was joyful yet urgent, all of it cut with a certain anti-war and anti-violent tenderness.

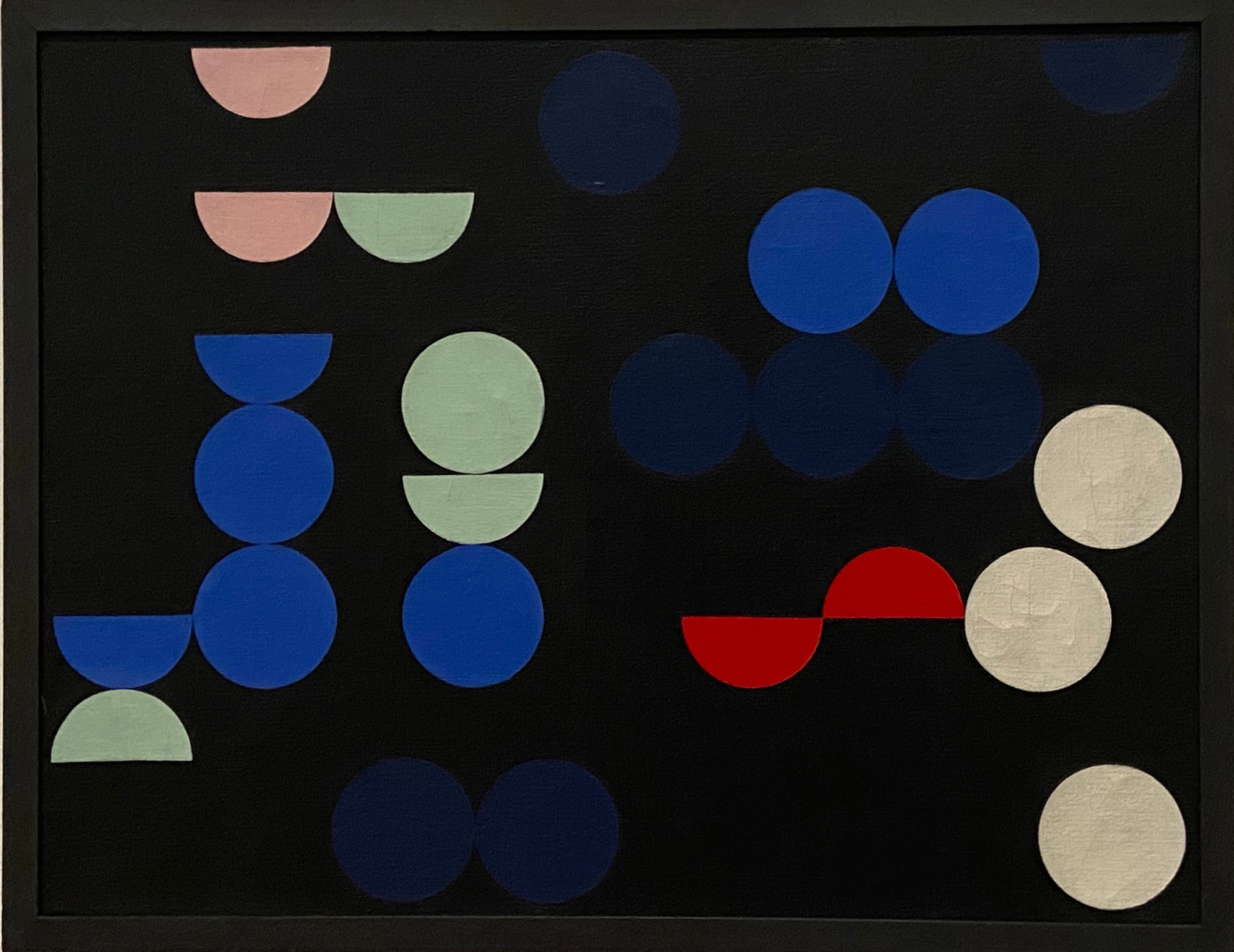

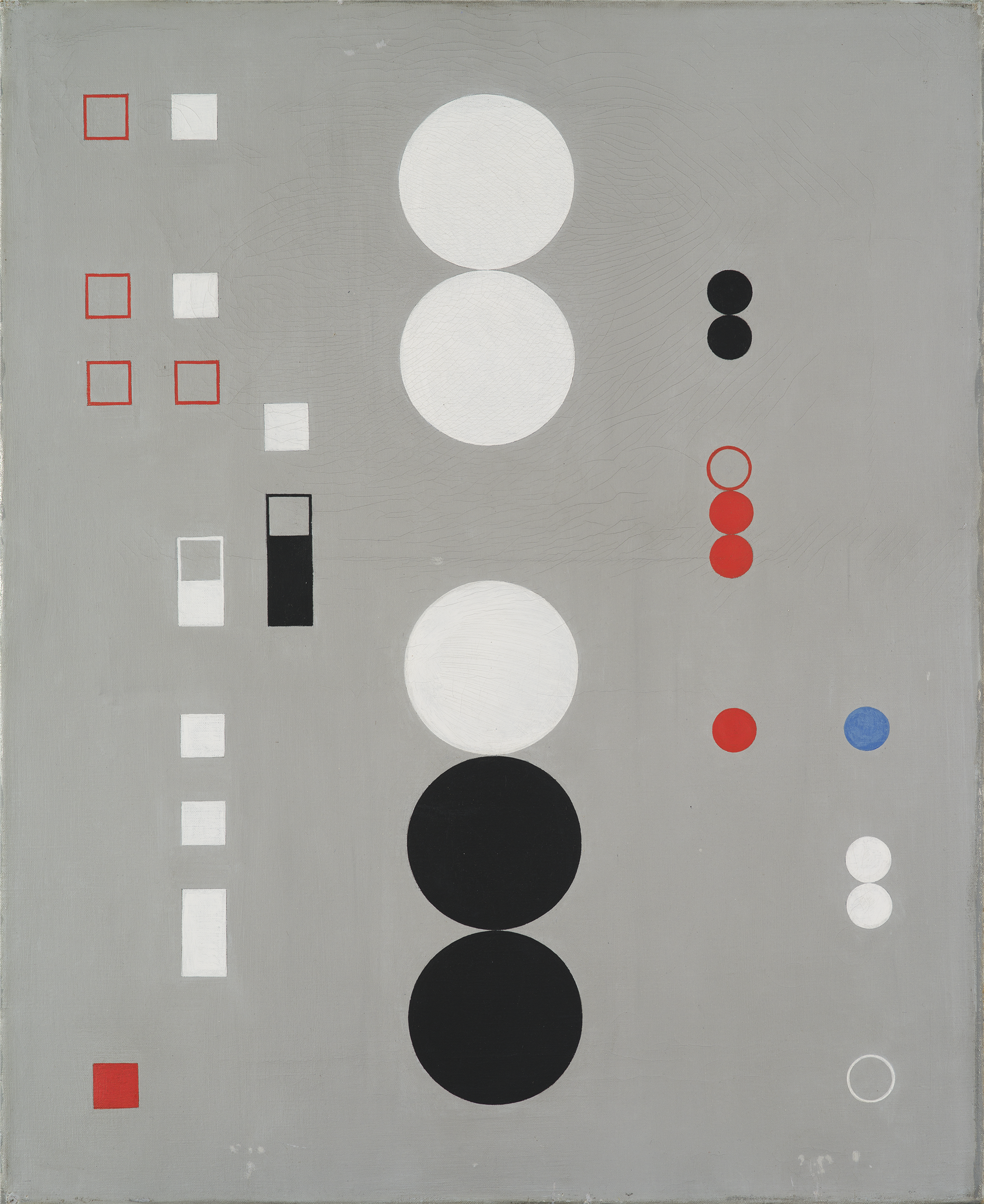

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition, 1930. Photo by Art is a word via Wikimedia Commons