Installation of “Fahara: Chicago in View” by Robert Earle Paige in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Nikola Bradonjic Photography.

The first floor of “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial at Cooper Hewitt,” Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution.

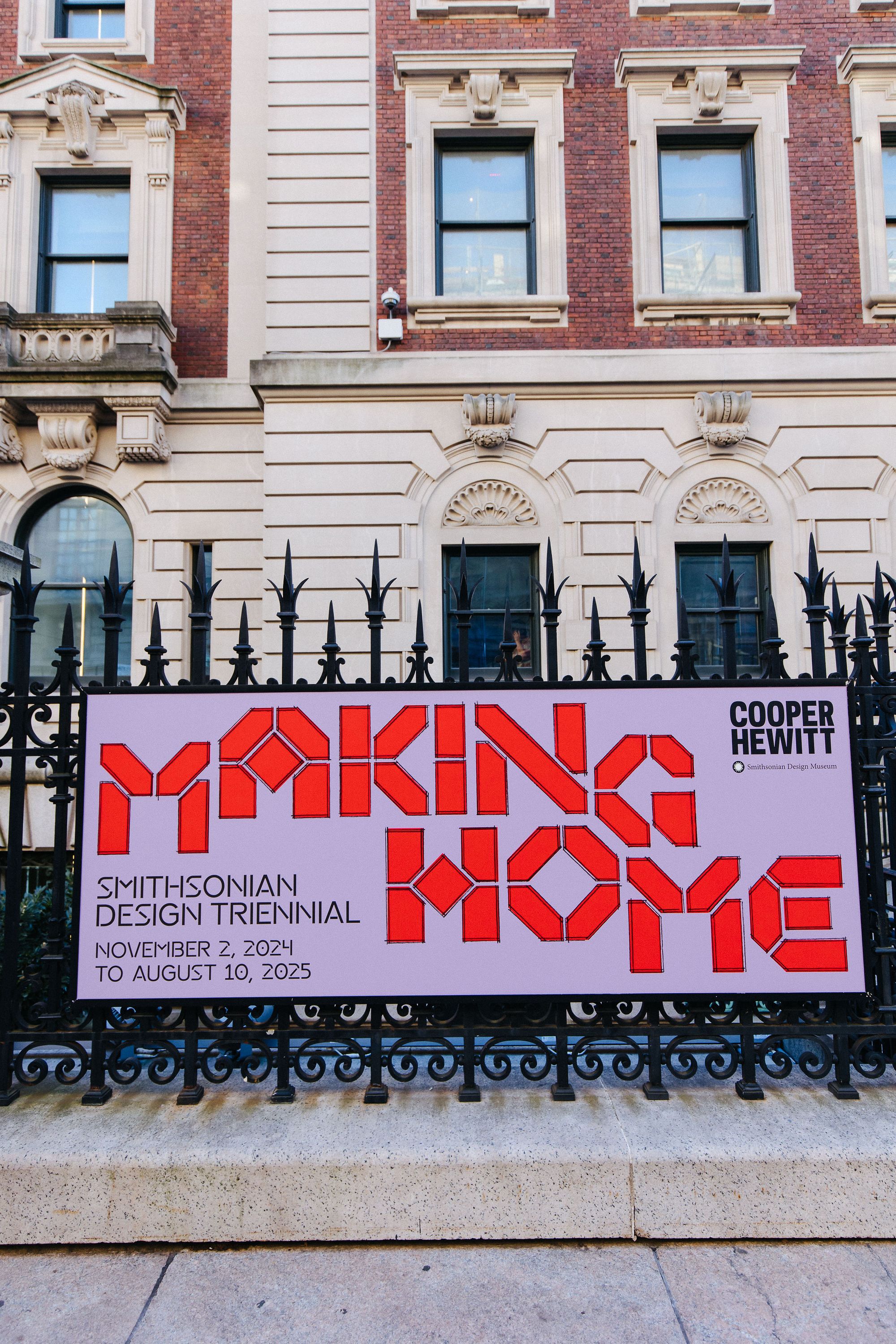

As I stepped into the Making Home — Smithsonian Design Triennial at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, I overheard a security guard pointing to a high-back wooden chair with plush orange upholstery in one of the installations. He mentioned that he had the exact same chair at home, adding with a smile that this installation really felt like, “a home within a home.” The chair was part of Living Room: Orlean, Virginia, a collaboration between baritone Davóne Tines, artist Hugh Hayden, and director Zack Winokur. Modeled after Tines’s grandparents’ Southern living room, the installation sets the stage for his sonic compositions and live performances, which fill the room with sounds including a grandmother’s hum, the deep vibrations of a cello and the sizzle of bacon. This sweet moment set the tone for my visit — the show was more than a design display; it was an invitation to explore the intimate and universal meanings of home.

The theme of this Triennial — exploring how we build and nurture a sense of home — feels more pressing now than ever. For me, the idea of being home has always deeply been related to the specific smell of orange blossom and being close to the sea; for others, it’s about the comfort and safety of an orange high-back chair. Our definition of “making home” continuously evolves, and with the ongoing global geopolitical shifts and mass displacement of people across geographies, it becomes impossible not to think of the fundamental right to have a home — a right that remains under constant threat for so many. Walking into the show, I learned a term that aptly encapsulates part of this threat: “domicide,” the systematic destruction of housing through military conflict. Mona Chalabi’s installation, Patterns of Life and Site Research, brings this concept into focus through large scale 1:10 maquettes depicting the devastation of homes in Mosul, Manbij, and Gaza — regions affected by conflicts involving U.S. taxpayer dollars. This mise en abyme moment within a federally funded museum prompts reflection on the U.S.’s role in such crises, underscoring the fragility of home and the profound loss that extends beyond shelter to a sense of belonging and community.

Installation of “Welcome to Territory” by Lenape Center with Joe Baker in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Ann Sunwoo © Smithsonian Institution.

The exhibition, spread across three floors and divided into the sections “Going Home,” “Seeking Home,” and “Building Home,” is tied together as a fearless examination of home not just as a physical space, but as a site shaped by cultural, social, and emotional forces. The curatorial tour de force, led by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León, and Michelle Joan Wilkinson, commissioned 25 site-specific works, all housed in the historic 1902 Carnegie mansion on Fifth Avenue. The mansion, designed in the Georgian Revival style, is dominated by rich wood details, including parquet flooring, teak wood paneling, and finely carved corbels.

The building itself is more than a backdrop; the architecture becomes an active participant in the narrative-building of the show. One of the exhibition’s greatest strengths is its bold, unrestrained engagement with the mansion’s architecture. This is evident both spatially, through the exhibition design and flow, and conceptually, as it intervenes, questions, and plays with the space rather than merely contrasting or conforming to it. The show contextualizes forces that have historically allowed for mansions of this grandeur and scale to exist, in terms of labor, material cultures, and craftsmanship.

Mona Chalabi’s installation, Patterns of Life and Site Research at “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution

From experience, I would argue that the best curators are those who think spatially, and no show is complete without a strong exhibition design and a cohesive visual identity. In this case, these were led by Los Angeles-based architect Johnston Marklee, with art direction and display design by New York City-based Office Ben Ganz, who together subvert tropes of domestic architecture. Walls are covered in scaled-up vinyls mimicking flowing curtains, checkered gray area rugs ground the rooms in an oversized familiarity, while soft, undyed Maharam slipcovers transform the existing museum furniture. The industrial materials — gray flooring, metal details — stand in sharp contrast to the mansion’s rich wood tones, layering warmth with a controlled coolness. Throughout, intimate “follies” (also designed by Ganz) are scaled down to household proportions, and are used to display captions on folded screens and wooden plinths that evoke in proportion chair backs and bookstands. Some of the typefaces used for the captions are based on the wood paneling patterns inside the mansion, while others reference the Carnegie logo stamped on steel beams, nodding to the industrial legacy that shaped both the mansion and Carnegie’s wealth. These details help each room feel both like an exhibition space and a living room.

The exhibition installations resonate with the mansion’s architecture, layering narratives of comfort, belonging, power, and reimagined domesticity into Carnegie’s once-private rooms. In the “Going Home” section, the Black Artists and Designers Guild (BADG) transforms Carnegie’s pristine personal library into “The Underground Library: An Archive of Our Truth,” a sanctuary for Black material culture filled with books and domestic objects that foreground historically marginalized voices, reframing the library as a space of inclusivity. In the adjacent room, designer Liam Lee and artist Tommy Mishima’s redesigned Monopoly set, Philanthropy, departs from the traditional board game by focusing on strategic grant-making, fundraising, and selling access to institutional research. The work critiques the economic forces that shape domestic life, and placed in Carnegie’s original office, it underscores how wealth and philanthropy have historically influenced the legacy and power of this home. As you make your way up the grand staircase to the second floor, look down to the rug by artist Robert Earl Paige, a pivotal figure in the Chicago Black Arts Movement. Drawing from West African textile traditions, the piece imbues the staircase with a powerful sense of cultural identity and history.

Installation of “Fahara: Chicago in View” by Robert Earle Paige in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Nikola Bradonjic Photography.

The Black Artists and Designers Guild’s Underground Library and Archive of our Truth at “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution.

If you decide to take the other stairs up, you will notice Joiri Minaya’s haint blue-colored ceiling installation in the hallway — the color is rooted in Gullah culture and believed to protect against spirits — which draws your eye upwards with representations of Caribbean flora, cotton, and wild rice. In Carnegie’s private library upstairs, the art-fashion-research collective CFGNY — whose acronym has stood for everything from “Concept Foreign Garments New York” to “Cute Fucking Gay New York” to “Certain Forgotten Gestures Near Yourself” — covers the room with timber frames and translucent coverings, revealing fragments of Lockwood de Forest’s original 1902 teak design. At the installation’s heart, a covered Tiffany hanging light becomes a light box illuminating uncredited artifacts from the museum’s collection, prompting reflection on overlooked cultural narratives embedded in familiar spaces. Together, these installations reimagine home through shared histories, economic reflections, and personal sanctuaries.

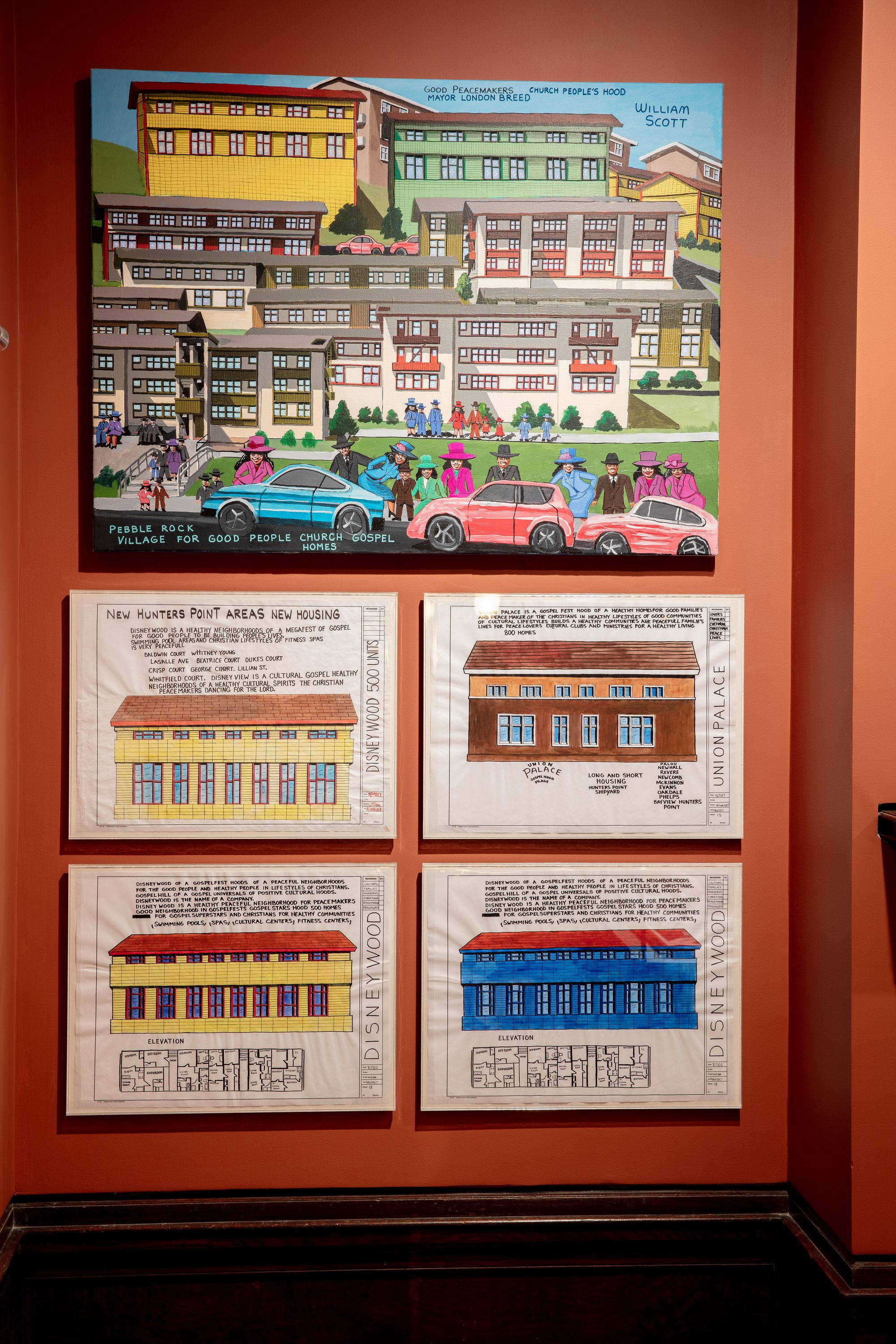

Other installations reconnect us with the idea that our bodies, senses, and imaginations are foundational to the making of home, somehow echoing the works of professor Clare Cooper Marcus’s work on the domestic space as an embodiment and a mirror of the self. Artist William Scott imagines San Francisco as an inclusive utopia, brought to life through his joyful, hand-drawn architectural models and paintings. Rooted in his personal experience living with autism and schizophrenia, his drawings represent spaces like hospitals not as sterile institutions but as places that nurture community and well-being. His work challenges the profit-driven norms of urban development, instead offering a vision where architecture becomes a support system for both physical and mental health. At its core, Scott’s designs remind us that the act of homemaking is not just about structure, but about fostering spaces where all bodies are cared for and celebrated. At the end of the hallway where Scott’s work sits, Curry Hackett’s and Wayside Studio cover Carnegie’s former dressing room in tobacco leaves, reminding us that a home is as much olfactory as it is visual. Similarly, biohacker Heather Dewey-Hagborg organized laboratory shelves filled with vials of (fake) blood to mimic a biobank, accompanied by the hum of industrial fans and the faint sound of whirring machines. This auditory backdrop, coupled with the clinical arrangement of the vials, creates a visceral awareness of the body’s presence, blurring boundaries between medical spaces and personal identities.

Installation of “Is a Biobank a Home?” by Heather Dewey-Hagborg in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Ann Sunwoo © Smithsonian Institution.

The artist William Scott’s work at “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution

The visual identity of “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, created by Los Angeles-based architect Johnston Marklee, with art direction by New York City-based Office Ben Ganz. Photo: Nikola Bradonjic.

The final section, “Building Home,” challenges traditional single-family housing models, inviting visitors towalk through full-scale 1:1 spaces. The late Terrol Johnson’s Everybody’s Home draws on Indigenous desert-living knowledge — specifically from the O’odham tribes of the Sonoran Desert in central Arizona — to present a vision of sustainable architecture deeply rooted in cultural wisdom. Casa de Senterrada’s clay construction addresses themes of slavery and demolition. Leong Leong’s prototype of an Indigenous form of Hawaiian architecture using novel lashing techniques and Hord Coplan Macht’s domestic-scale vignettes of senior living residences examine comfort levels, impairments, and shelter as support.

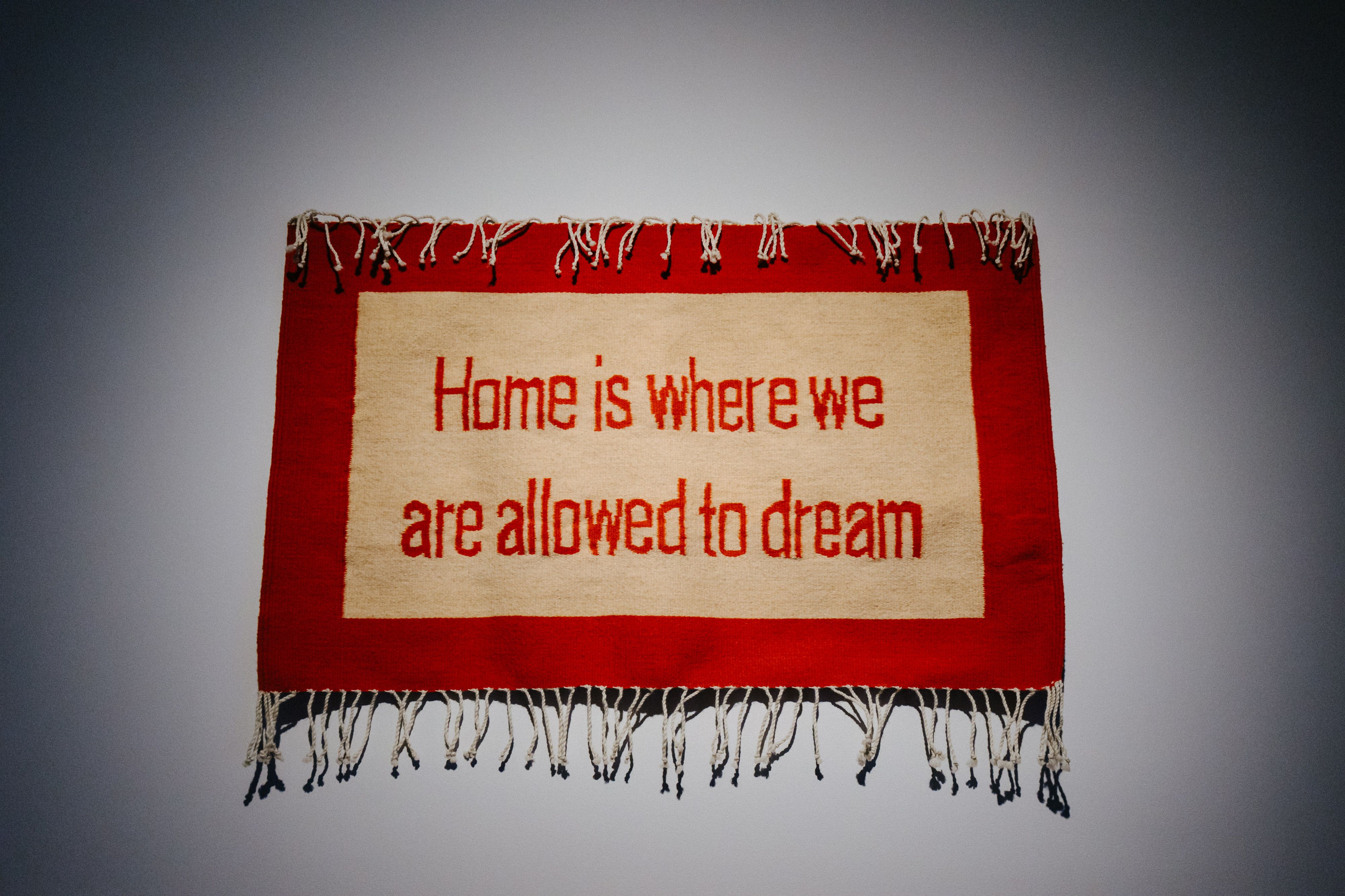

To conclude, one of the most tender and necessary works in the show — yes, I’m biased — is PIN–UP’s Dream Homes, co-directed by PIN–UP publisher Michael Bullock and filmmaker Michael Cukr, a commission that’s especially meaningful in today’s hostile political landscape. This 30-minute documentary delves into diverse forms of communal living within three queer collectives — Lupinewood, Ten of Cups Farm, and House of GG — across rural and suburban America. It explores alternative alliances and reimagines what it means to live together, moving beyond the traditional single-family home to envision new kinds of domestic structures and systems of kinship that place solidarity at the center. This resonates with a question posed by curator Hashim Sarkis at the 2021 Venice Biennale that I still think about — “How will we live together?” In the all-black carpeted room where the documentary is playing, a tapestry by artist Andy Medina hung above the fireplace reads, “Home is where we are allowed to dream” — a reminder that home is more than a shelter. Rather, it’s a space constantly being shaped by social interactions, economic, political, and environmental forces, as well as a framework through which we can reimagine alternative forms of togetherness.

Installation of “Dream Homes” by PIN–UP in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution.

Andy Medina’s tapestry in the installation of “Dream Homes” by PIN–UP in “Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Nikola Bradonjic.