Sick Architecture, installation view. Photograpy by Kristien Daem

Aino and Alvar Aalto, sanatorium of Paimio, Finland. Exterior view of the south façade, 1930s. Courtesy of the Alvar Aalto Foundation. Photo by Gustaf Welin.

“Throughout history, you have multiple examples of this idea that at the center of architecture there are these perfect, able masculine bodies,” says Beatriz Colomina, co-curator with Nikolaus Hirsch and Silvia Franceschini of the exhibition Sick Architecture at CIVA in Brussels. “We see it from Leonardo to the Modulor. Yet few people fit that ideal — in fact, they’re the exception. The rest of us all live with ‘sickness’ in one form or another. It’s a condition of normality.” This, as the exhibition makes clear, is something that Aino and Alvar Aalto intuitively grasped when designing the Paimio Sanatorium in 1929: Aalto was unwell during part of the process, and being confined to his bed helped the couple understand that, rather than catering to the standing human being, the sanatorium must respond to the horizontal body, the person “in the weakest position.” Yet even the able masculine body is arguably “sick” in the eyes of architecture, since the primary purpose of buildings is to shield vulnerable humans from any harm the unmediated environment may throw at us. “For this reason, the title of the exhibition irritates some architects, because they think their job is to heal,” says Hirsch. “But we also talk about sick buildings that make people ill.”

Covering everything from Ellis Island to man caves to Maggie’s Centres, this ambitious show, put together with research contributions from Colomina’s Princeton students, seeks to unpick the multiple ways in which ideas about sickness inform architecture. The first thing visitors see are oral capsules, some of Hans Hollein’s 1967 “architecture pills,” which he would theorize a year later in his manifesto Everything Is Architecture. “Through the inclusion of sprays, inflatables, electronics, and pharmaceuticals,” writes Bart-Jan Polman, who researched this part of the exhibition, “Hollein proposed an understanding of architecture as a total environment of different media, including mental states.” This opens the door not only to medical prescription of pharmaceuticals but also to contemporary drug culture (a leap Sick Architecture doesn’t entirely make, stopping at 1960s experimentation with LSD): the nightclub or rave is arguably a hedonistic, self-healing environment for those seeking solace from workplace stress.

Hans Hollein, Non-physical environment, 1967. Photo courtesy of Private Archive Hollein.

Sick Architecture, installation view. Photograpy by Kristien Daem

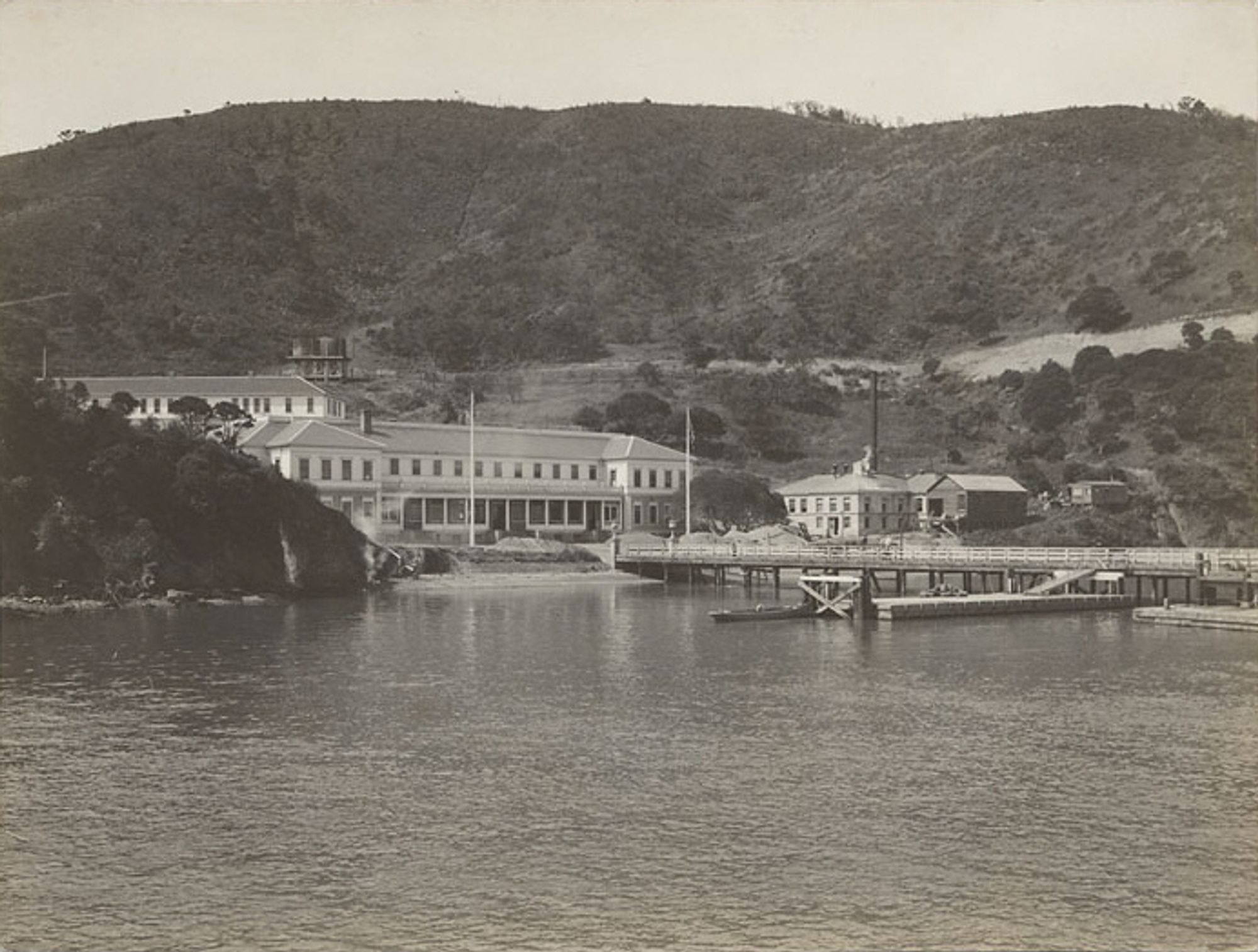

Angel Island Bureau of Immigration inspection and detention facility in San Francisco.

Sick Architecture, installation view. Photograpy by Kristien Daem

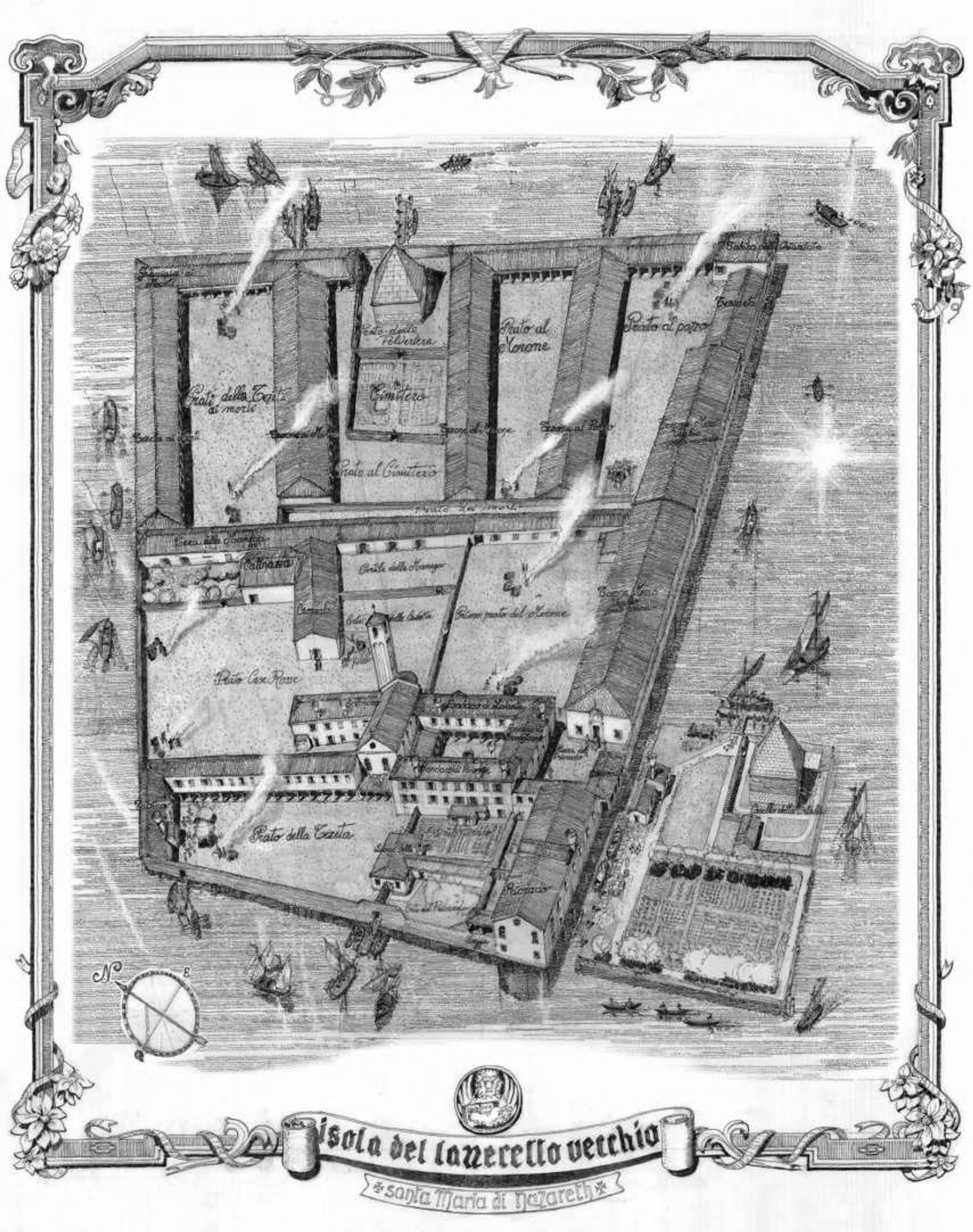

Instead, the show’s primary concern is the relationship between architecture and medicine — which is ancient, ambiguous, and revealing. Established in 1423, Venice’s Lazzaretto Vecchio, a plague hospital on an island in the lagoon, was the first time anyone tried to break the chain of infection in this way. But this space fortified the stigmatization and rejection of the sick as a contagious other, especially if they came from elsewhere — the 1468 Lazzaretto Nuovo quarantined the crews of ships arriving from places where epidemics were thought to have broken out. Four-hundred-and-fifty years later, similar thinking informed the treatment of Asian immigrants arriving in San Francisco, one in five of whom were turned away at the infamous Angel Island Bureau of Immigration inspection and detention facility, which operated from 1910 to 1940 and was nicknamed “China Cove” (among the thousands who passed through it was I.M. Pei, in 1935). Racism crops up time and again in Sick Architecture, from the different housing types offering varying degrees of protection against malaria that were built by the U.S. during the construction of the Panama Canal (1904–14), to the cordon sanitaire established between white and non-white districts in Lubumbashi, Congo — a 1,600-foot-wide unbuilt strip of land meant to protect the colonizers from the “contaminated” cité indigène.

A depiction of the Lazzaretto Vecchio in Venice, c. 17th century. Drawing by G. Fazzini e G. Barletta © Lazzaretti Veneziani

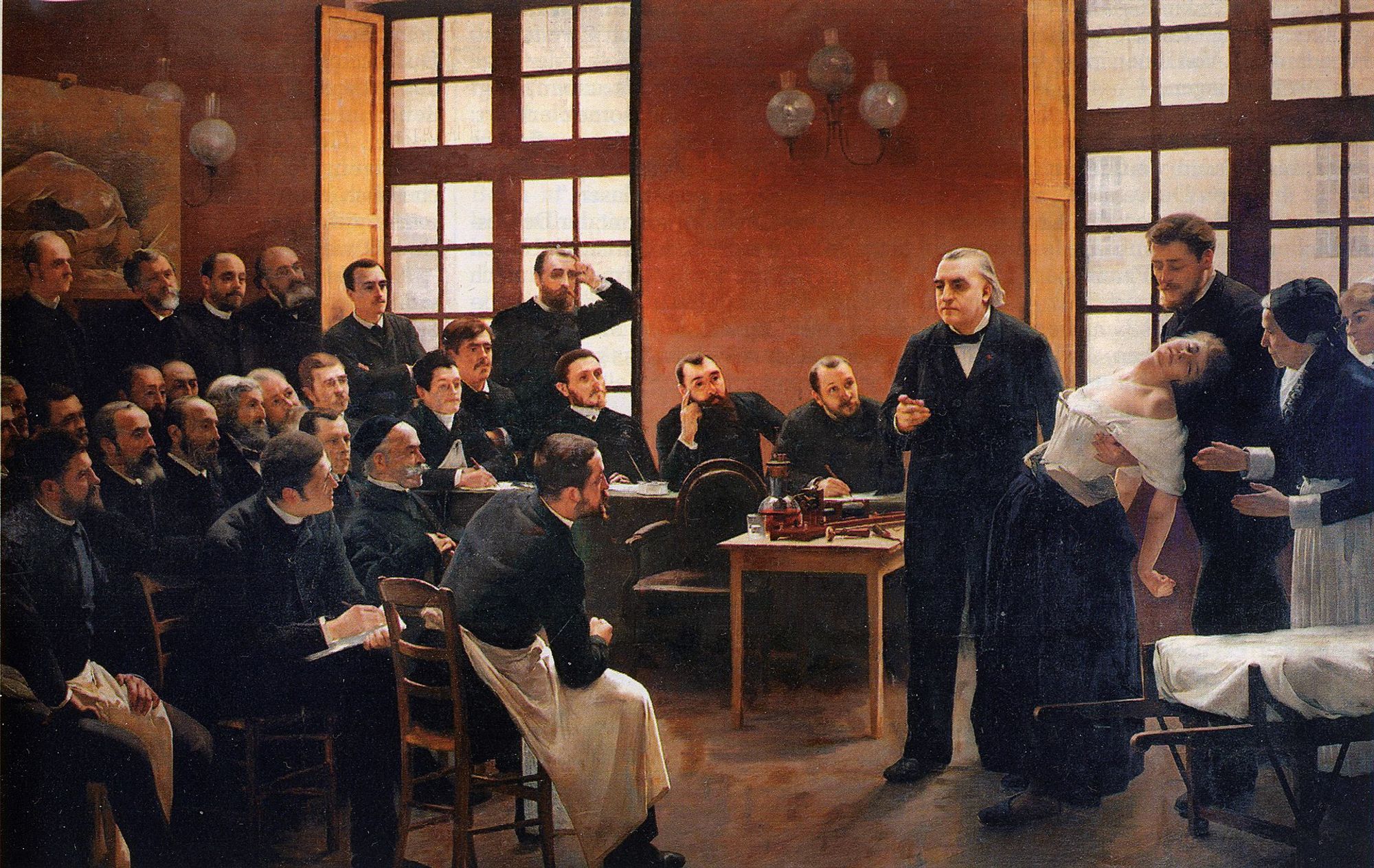

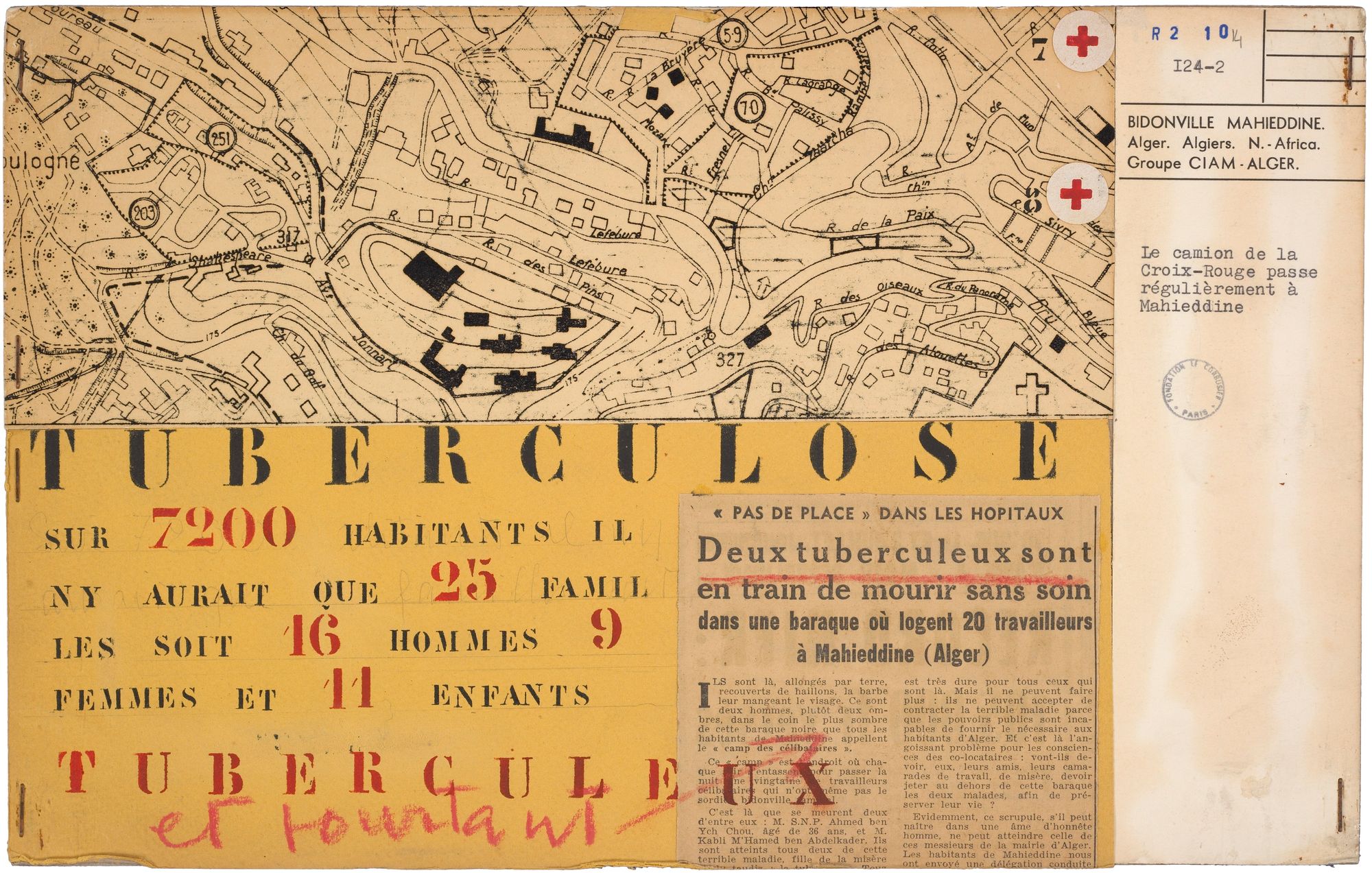

Another field the exhibition explores in depth is the relationship between tuberculosis and Modernism, an aspect of 20th-century design that will be familiar to readers of Colomina’s 2019 book X-Ray Architecture. Antibiotics won out over the sanatorium — the drug, which was developed in the 1940s, proved much more effective in curing the disease than sanatoria (at any rate until now and in countries with developed health-care systems — TB still kills over 1.5 million people a year worldwide, and concern is growing over treatment-resistant strains). Architects of the hygienist strain had to find other justifications for their ascetical-clinical aesthetic fetish. “Streptomycin and related drugs became available between 1943 and 1953,” explains Colomina, “and within ten years the same architects start claiming that their architecture, which they previously peddled as great for TB, is good for your mental health. [Richard] Neutra no longer presented himself as a doctor but as a shrink — and from there to experimentation with LSD, the path is obvious.” Inevitably, the relationship between architecture and mental health also looms large in the show, with tales from the bad old days — Jean-Martin Charcot’s staging of hysteria at Paris’s Pitié-Salpêtrière, for example — contrasted with attempts at reform, such as architect Nicole Sonolet’s projects in the 1960s and 70s for community-based mental health care in and around the French capital (Sonolet is one of many neglected figures the show brings to light).

DS+R, Exhaustion, 2017; film still. Directed by Elizabeth Diller. Commissioned by Fondazione Prada.

Given recent history, Sick Architecture appears very timely. “COVID is a reference point that I think allows everyone to understand architecture and illness in a different way,” comments Hirsch, and the ongoing pandemic is of course addressed in the show, from Madrid trade halls converted into emergency hospitals to Liz Diller’s video Exhaustion, which highlights the parallels between two defining events of 2020 in the U.S.: SARS-CoV-2 and George Floyd’s death. One of the COVID-related exhibits triggers an intriguing thought: what if human beings themselves were in fact a form of sickness afflicting the planet, a pathogen to be eliminated? As Clemens Finkelstein writes, “Concerns about human and planetary health have always been closely entangled, with architecture as a mediating agent between cosmic and biological bodies. The standstill of human activity that occurred when government lockdown protocols turned cities into ghost towns during the COVID-19 pandemic also slowed down the ubiquitous vibrations of the Earth by up to 50 percent, and culminated in the longest period of seismic quiet in recorded history.” If Bezos, Musk, and co. have their way, one day we’ll leave behind our sick world to infect the rest of the universe — if, that is, Gaia’s immune system doesn’t kill us off first...

A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière by André Brouillet, which depicts Jean-Martin Charcot’s staging of hysteria to a group of students at Paris’s Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital.

Sick Architecture, installation view. Photograpy by Kristien Daem

Presentation panel on tuberculosis in Bidonville Mahieddinne, for the 9th CIAM congress in Aix-en-Provence, 1953. Courtesy Fondation Le Corbusier