Is it because, at the design phase, architects don’t really take construction methods into account? Or is the building industry resistant to change? Or both?

Perhaps both. We complain about construction contractors, but I’m sure they also complain about architects. At the same time, I know there’s a willingness to understand each other, and I also think there’s great acceptance in the construction industry of radical or highly designed architecture. Designers might not get exposed enough to the actual building industry. As design architects in the U.S., we often don’t have the fee to stay on until the very end of a project. Typically, a design architect like myself will do the schematic early phase, after which comes design development, or DD, when a lot of details are thought out and priced, and then it goes to the construction-document phase, or CD, where it’s almost a preparation of the site and a bid to the contractor. Typically, the design architect drops off at the end of DD and hands it over to the executive architect who does CD, where you get into the nitty gritty, the technical reality of the design. In our office, we’re trying to overcome that divide by being involved until the very end.

You work with a lot of different typologies — is there one you feel more comfortable with?

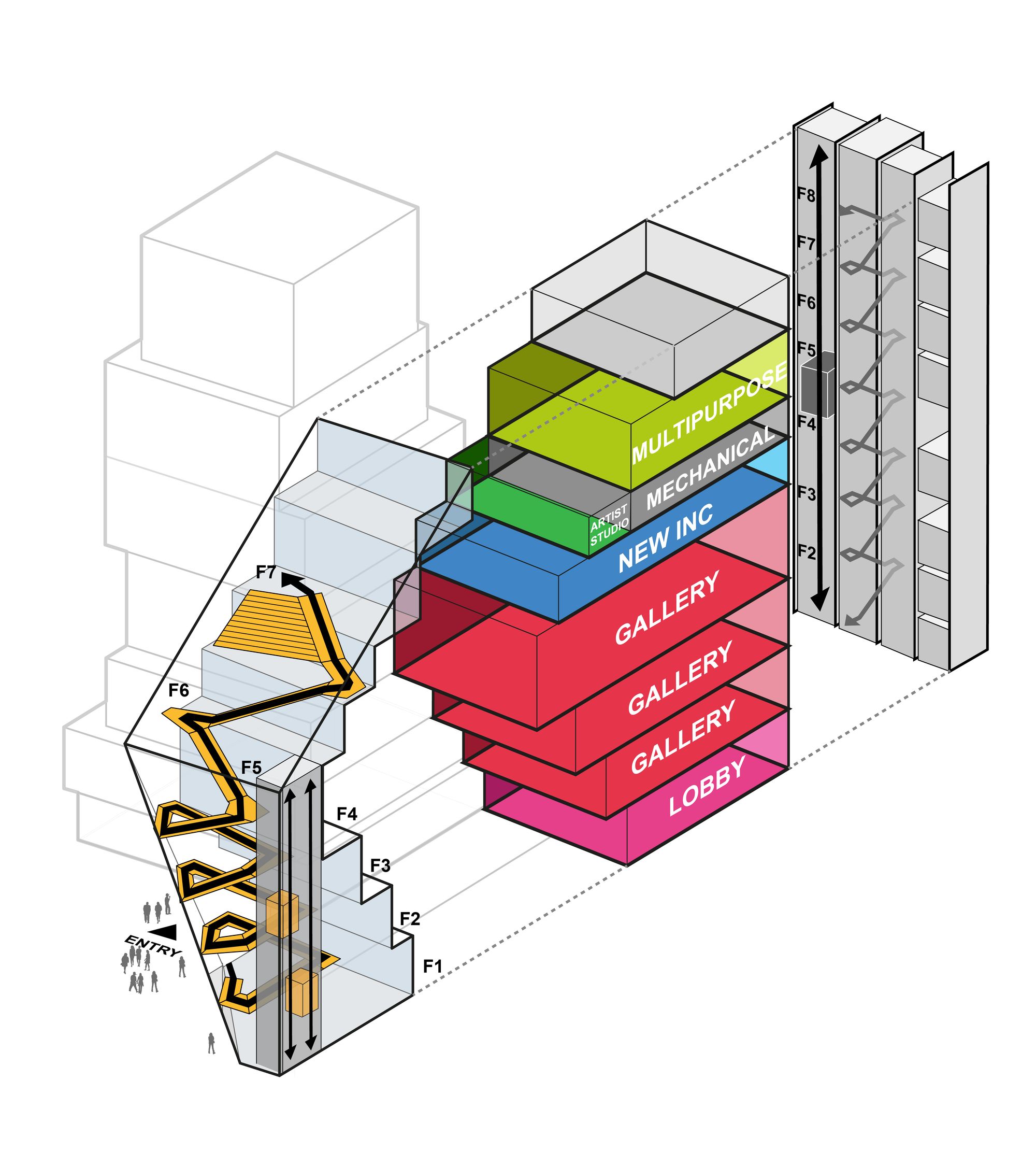

If I had to choose, I think I’d choose art projects. Especially the museum typology, which is evolving quite fast and becoming more like a public space, almost an extension of the urban condition — there’s a variety of activities and events centered around the community beyond looking art happening in between the exterior and interior. The potential of these undefined, unprogrammed buffer zones in between art and urban life is really exciting. In general, I think architecture today is too highly programmed. Cities are so highly regulated. In Japan, you can’t smoke on the street — there’s a designated zone. There’s surveillance in a lot of places, and big data controls the movement of traffic and pedestrians. Although technology allows people to use architecture more freely, it’s lacking this more undefined area. Architecture should respond by providing more open-ended spaces — it’s the architect’s role to create that part of the canvas that’s not painted. With the New Museum, for example, the face of the building that looks out west toward the Bowery was conceived as a kind of buffer zone where a lot of different improvisational programming could happen, almost as an extension of the city.

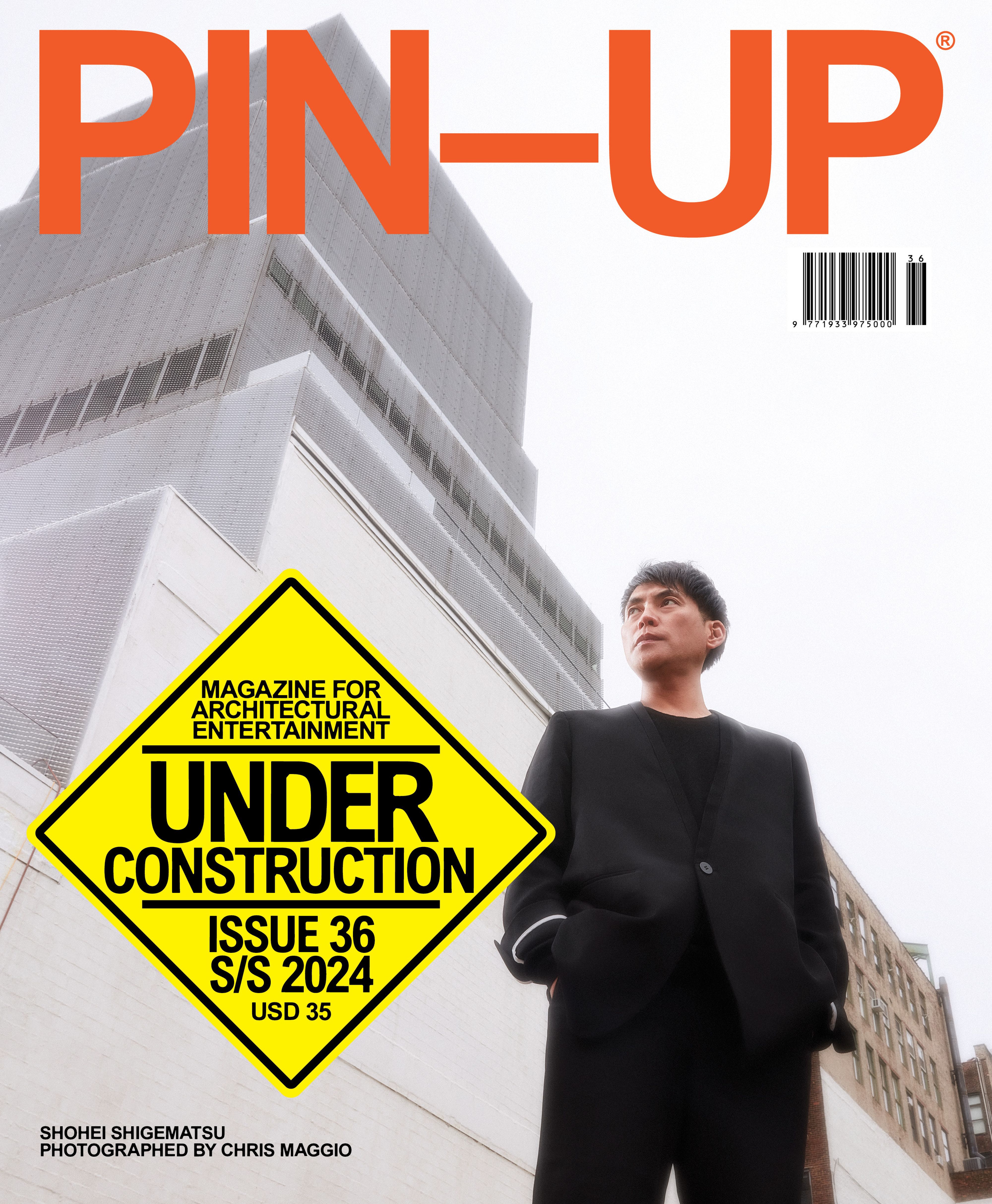

Can you tell me more about the New Museum project — I know you don’t pick favorites, but this one is clearly important.

As I said earlier, I was a project architect for the Whitney extension back in 2001, an enlargement of the Marcel Breuer masterpiece, trying to create a statement that the museum as a typology was evolving. With architecture, you don’t get exposed to the same conditions so often, but the New Museum is a strikingly similar case: two decades later we find ourselves once again in the heart of Manhattan connecting with a masterpiece of modern, contemporary architecture. With the Whitney project, of course I had different opinions because I wasn’t fully leading the project — but that experience of failure taught me a lot that I can now apply to the New Museum. So it’s very important in terms of my professional evolution.

OMA’s proposed extension to Breuer’s Whitney building came in 2001, 35 years after it was first completed. SANAA’s New Museum opened in 2007, just 17 years ago.

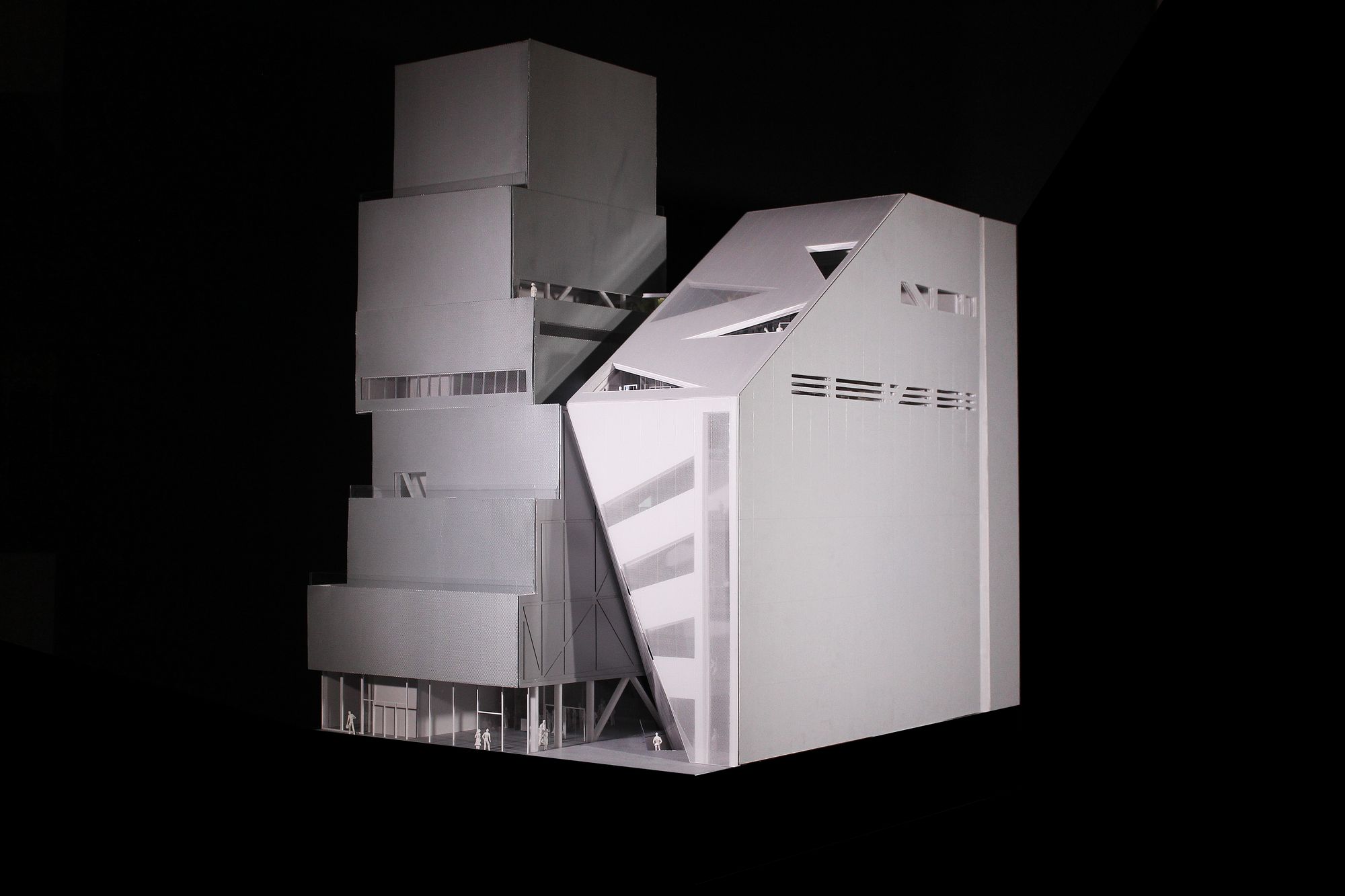

Yes, we talk about that a lot. An extension typically comes around 50 years later, so the previous architect may have died or may not be active anymore. But here, it’s a Japanese duo [Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa of SANAA] who are quite active, and the museum is still considered a piece of contemporary architecture. We were very aware of how tricky it is to add an extension to that. I think we arrived at something slightly different that respects the verticality of the existing structure while using the horizontality of the given site. That fine balance between being not too respectful but not too overriding came out of the initial research. In the end, I think our extension will look like it was built in the same era as the original.

Your design reveals a part of the existing museum that is currently obscured by the neighboring structure.

Yes. We also talked about this with Sejima-san. An extension typically obscures part of the original building, but here we are exposing more of it, because our project is set back a few feet. That previously unseen, now-revealed part of the old building became a kind of collaboration with Sejima-san, a conversation between both buildings.