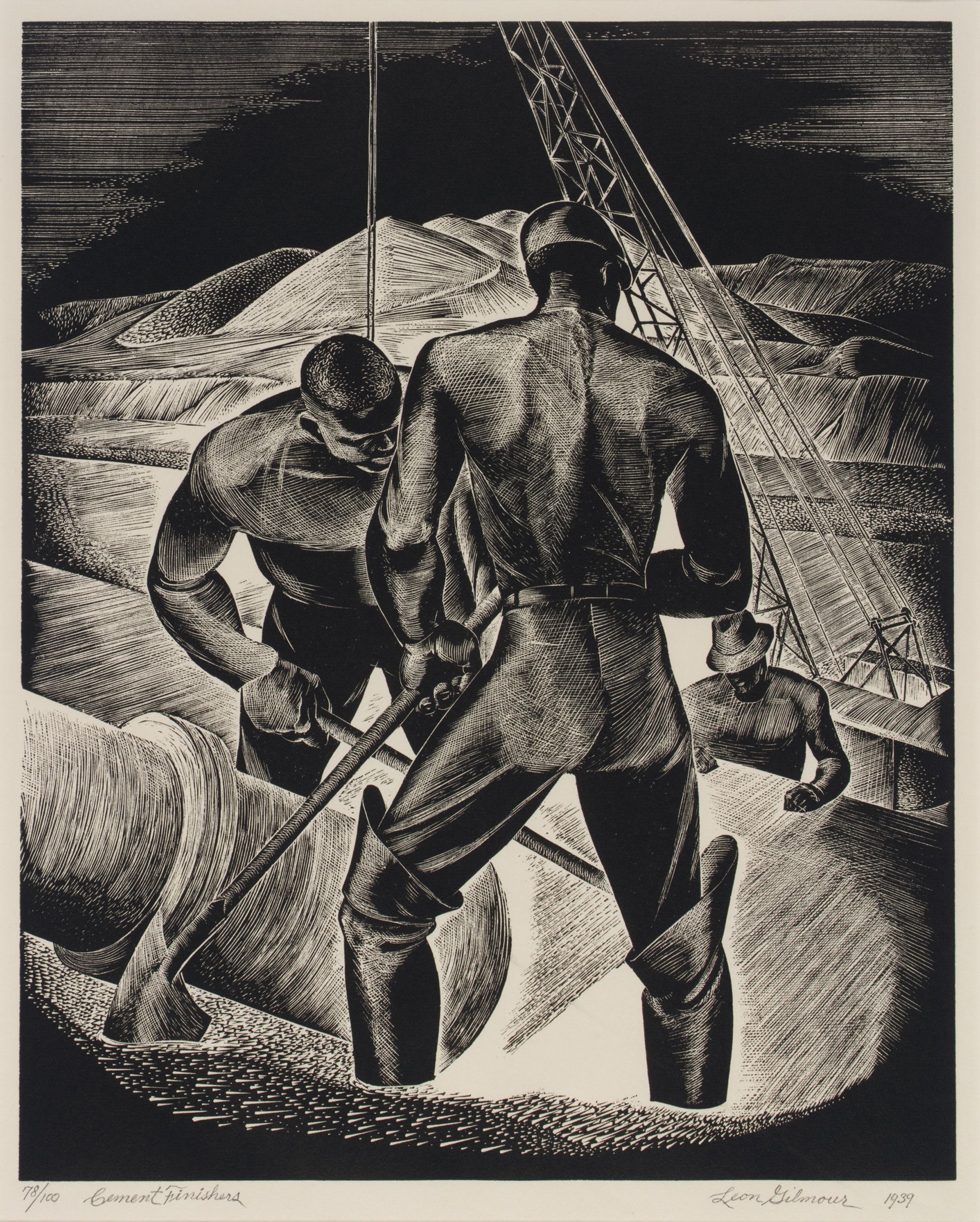

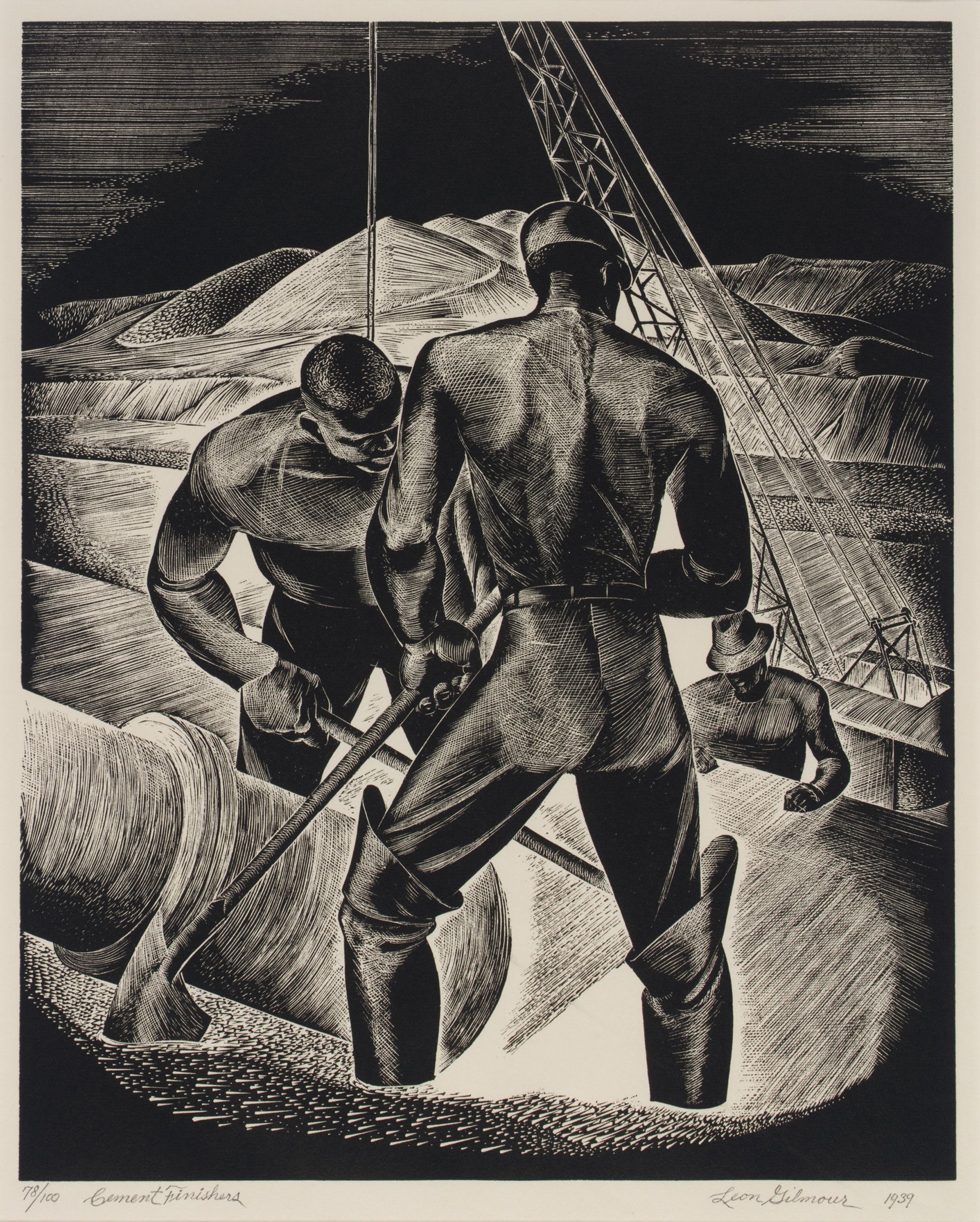

Leon Gilmour, Cement Finishers, 1939, wood engraving on paper, image: 10 x 8 1/8 in. (25.5 x 20.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the artist, 1989.100.5, © 1939, Leon Gilmour.

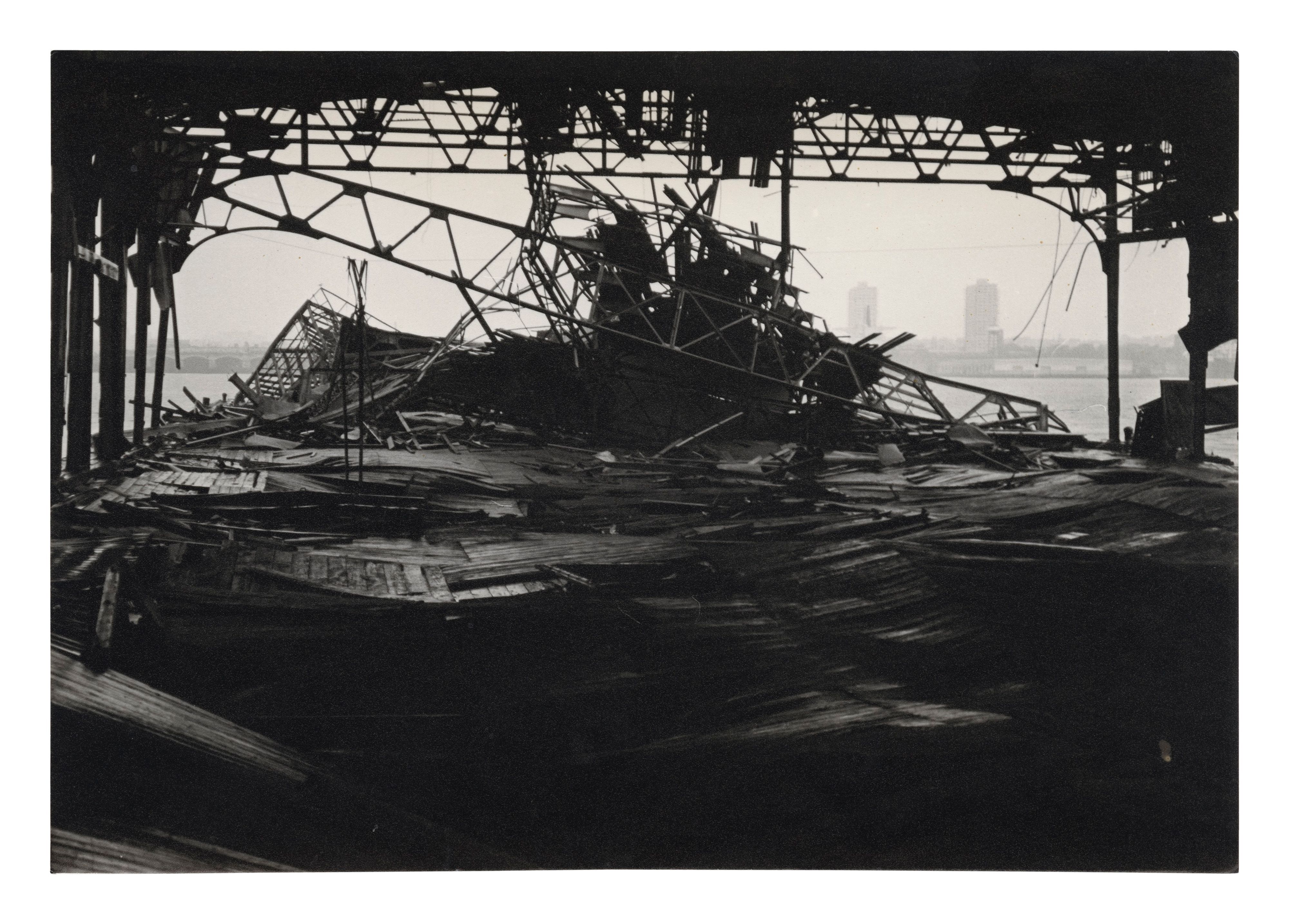

Alvin Baltrop, “The Piers (wreckage)”, n.d. (1975-1986), silver gelatin print. Courtesy The Alvin Baltrop Trust and Galerie Buchholz.

Pristine Art-Deco lobbies and the infamous suicide decks of modern skyscrapers are not sexy by any definition, but homoeroticism manages to seep through the urban work sites that precede a building or the final form of contemporary “erections,” so to speak. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the bodily semiotics of construction workers: uniforms function as standard garb in fetishistic roleplay; protective straps and heavy duty belts wrap tightly around the thighs, resembling taut leather harnesses; hammers and drills resemble the disembodied phallus, while rope heightens pleasure in sadomasochistic rituals. Pedestrians trying to catch a glance at construction sites, eager for a flash of men at work, are today’s peepshow voyeurs. Fantasies go on. Might the other side of the hole reveal an erotic link between industrial architecture-in-progress and working men?

Since the latter part of the 20th century, the meaning behind masculine camaraderie in construction sites and beyond has been contested in several academic fields. In the text, “Between Men,” queer theorist Eve Sedgwick defines homosocial desire as same-sex relationships driven by changes in class within a gendered system. Sedgwick elaborates on the homo-and-hetero binary by suggesting that anxiety around gayness — homophobia — restricted men from impulsive desire. Examples of repressed sexuality manifest in phenomena such as “bromances” amongst typically misogynistic men or the now blasé, ass-slapping in team sports. On this note, the social customs that define masculinity have been shaped, at least in part, by the sexual politics of earlier institutions of working men.

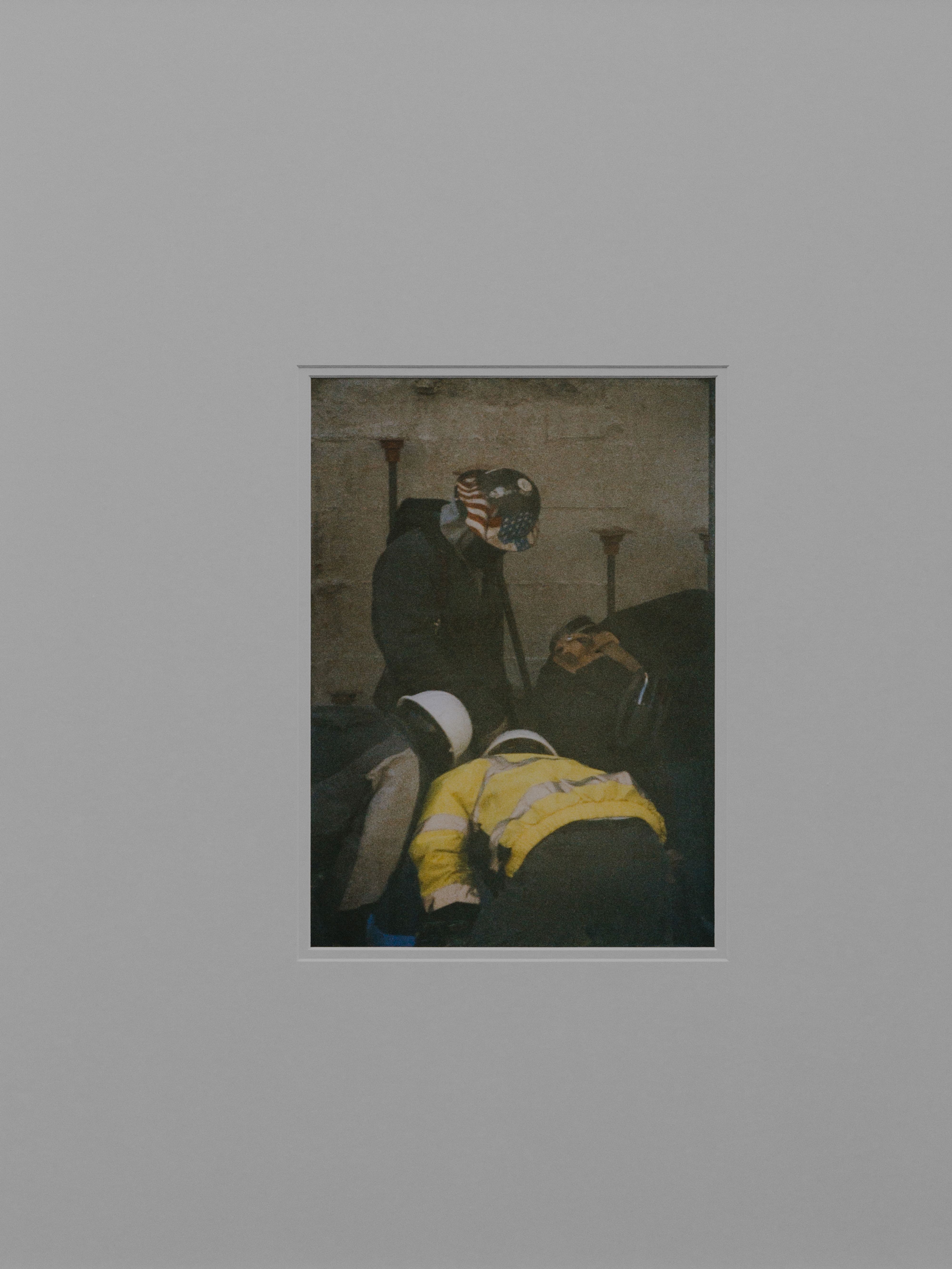

Daniel Shea, Cruising II, 2016. Archival Pigment Print, Matboard, Wood Frame 22x32".

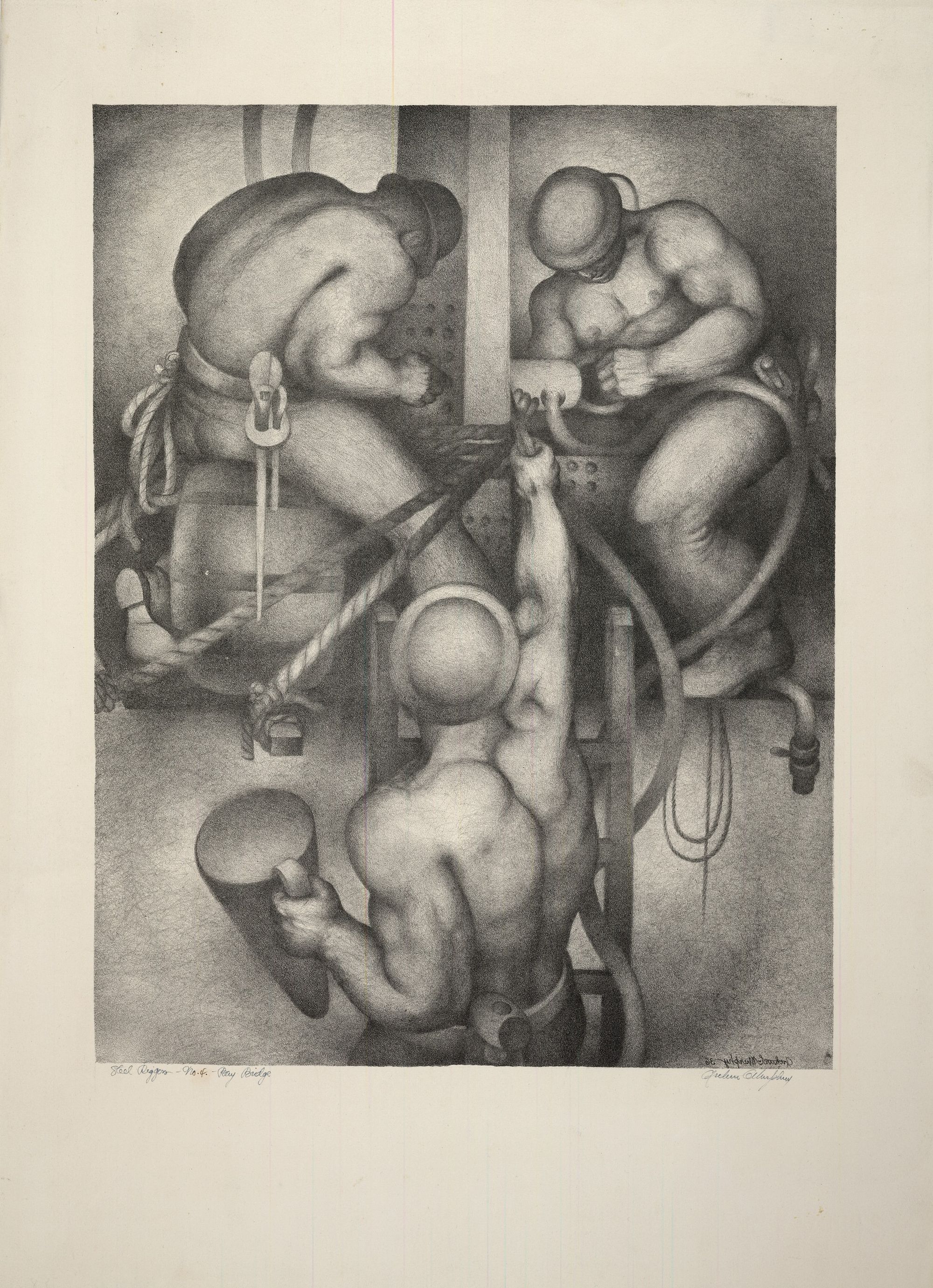

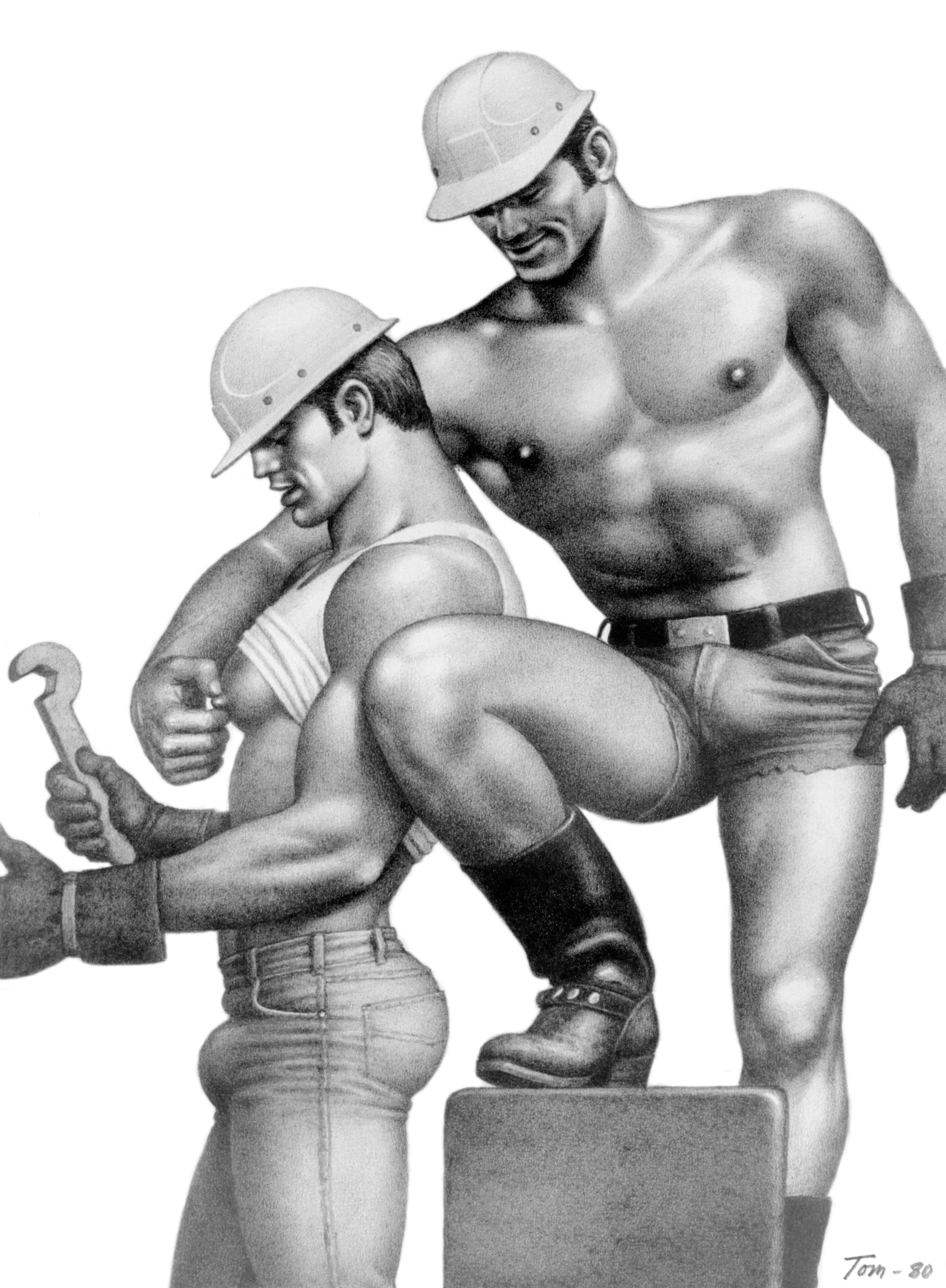

As the concept of masculinity became synonymous with control over the means of production, platonic relationships inherited some of the intimate, even erotic, qualities as represented in American painting from the industrial 1930s. Before Tom of Finland and Wakefield Poole championed the hyper masculine figure in explicit drawings, paintings, and experimental pornography, heterosexual painters attempted to legitimize the working class by unconsciously sexualizing the proletariat. Social realists, such as Leon Gilmour and Carl Hoeckner, rejected strict formalism by accentuating the muscularity of steel workers. This newfound emphasis on physique slowly transformed oppressive conceptions of working men through an affirmation of purpose vis-à-vis the working body. Dominance permeated all facets of life until the proliferation of gay identity slowly subverted the image of the worker.

Leon Gilmour, Cement Finishers, 1939, wood engraving on paper, image: 10 x 8 1/8 in. (25.5 x 20.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the artist, 1989.100.5, © 1939, Leon Gilmour.

Arthur Murphy, Steel Riggers--No. 4--Bay Bridge, 1936, lithograph on paper, image: 15 1/4 x 11 3/4 in. (38.7 x 29.9 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Jean Nichols, 1974.38.67.

TOM OF FINLAND © 1980 Tom of Finland Foundation.

During the wake of the Great Depression, the Chrysler Building appeared from the shadows of the New York City skyline as the new center of commercial enterprise and monolithic American corporations. The Empire state of mind reflected the capitalist order — equating privacy and freedom with free-labor — and appropriated public space by placing swaths of corporate classes in business districts with large office buildings. Far from J.G. Ballard’s foreboding novel, Crash (1973), in which residential skyscrapers and their inhabitants perpetuated the social hierarchies and class antagonisms of the outside world, buildings throughout lower Manhattan historically housed lower classes and working artists with preferences for uninhibited lifestyles, and more importantly, unpoliced space.

Henri Lefevbre, the Marxist philosopher and sociologist, borrowed from psychoanalytic principles when coining the term phallic verticality to suggest that systems of injustice were present not only in the superstructures, but spatial ordering cities. He believed modern architecture could limit social potential by defining both a scene — where something takes place — and an obscene — an area in which everything that cannot, or may not happen on the scene is relegated — thus rendering whatever is inadmissible, be it monstrous or forbidden, to hidden space on the near or far side of the periphery. These secret domains inevitably established areas for the gay populace, not as participants, but spectators seeking refuge from the oppressive reality of American decline.

Real-time reflections of supposed cultural obscenity emerged after the collapse of the West Side Highway in 1973. The cover of photographer Alvin Baltrop’s book, The Piers (2015), depicts two men having penetrative sex amongst piles of decomposed timber and fallen steel. Baltrop’s photographic oeuvre attested to the ulterior function of Pier 52 as a site for orgiastic homosexual activity. Through his surveillant lens, men became figures — wandering through the minefields of solar strobes inside vacuous warehouses — lost in a post-coital haze. Baltrop’s photographic subjects offer an imprint of vulnerability masculinity when compared to the dramatic figure championed by the American social realists. Men turn away, often in profile, as the camera hones in on their lithe features, alluding to poverty and destitution. Having served as a medic in the Vietnam War before attending the School of Visual Arts, Baltrop himself was no stranger to traditional masculine tropes.

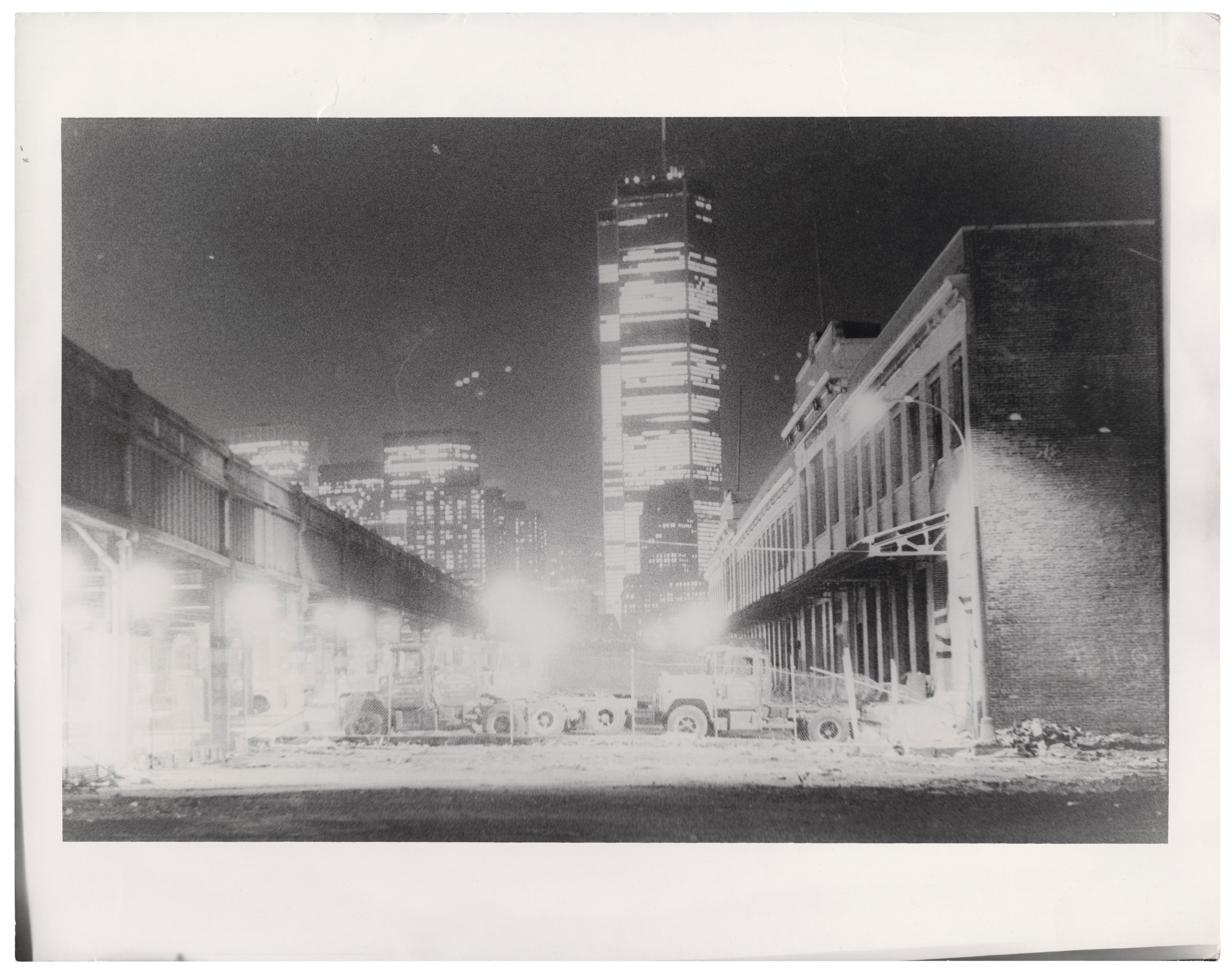

Baltrop’s visual language was characterized by the negative space of decaying landscapes — dark shadows, shattered glass, panoramic views of liminal interiors, assemblages of decomposition in harsh contrast with the rigid silhouette of the Manhattan skyline — reinforcing the continuity between sexuality and material deconstruction. Critique with a sole focus on the hedonistic appeal of Baltrop’s monotone imperfections glances over transgressive architectural models found within waste. Baltrop's impetus remains unknown, but a sliver of subliminal evidence lies in one of his only titled works: The Piers — Collapsed Architecture.

Alvin Baltrop, “World Trade Center at Night (Westside Ghost)”, n.d. (1975-1986), silver gelatin print. Courtesy The Alvin Baltrop Trust and Galerie Buchholz.

Baltrop was not alone in making strategic use of the detritus along the Hudson River. In 1983, David Wojnarowicz and Mike Bidlo curated guerrilla art exhibitions inside the Ward Line Pier. Site-specific installations and sculptures of mutilated art critics populated the interiors of Pier 28, signaling Wojnarowicz and Bidlo’s antipathy towards rapid commodification in the art world as dispossessed groups of people felt the loss of freedom. Spaces once defined by sexual liberty vanished while acts of illicit desire among gay men were confined to the isolation of clubs and even pornographic booths in adult video stores. Municipal zoning regulations such as LU03 and initiatives like the 42nd Street Redevelopment Project insidiously corporatized the life force around the Hudson by keeping obscene activity inside sex chambers along Midtown.

Decades later, David Hammons’s installation, Day’s End (2021), funded by the Whitney Museum of American Art, sprung up around Hudson River Park. Hammons’s piece has been critiqued for overlooking the artistic contributions of sexual minorities and anarchist artists once deeply intertwined with the area. Further north, Pier 55 houses Little Island (2021), the two-acre, man-made artifice planned by London-based design and architecture firm Heatherwick Studio. Resolute in its place along the West Side Highway, its completion faced a four-year delay after The City Club of New York contested the ethical use of public projects funded by private investors.

The breeding grounds around Riverside Drive, which bore witness to radical horizons and queer futurity, continue to be exonerated by development-driven revisions to the piers. The breeding grounds around Riverside Drive, which bore witness to radical horizons have been exonerated by static quests for sexual pleasure and large-scale urbanization, but their erotic lineage unearths a historic formula in architecture with deeper significance than the aesthetics of ruin: sexual deviants are assigned to abandoned environments, deterioration follows, making room for the development of something new from the shards of queer life. The work site is then reimagined as a microcosm where the fantasies of gay men and histories of queer worlding collapse into the sociospati`al dynamics of masculinity under construction. Cruising the West Side highway, I wonder about the erogenous potential of places where resistance lived. Unlike the capitalist topography they have become placeholders for; images of the worker — one of a hopelessly defensive, but titillating sexuality — flash through fragments of an already ruined infrastructure.

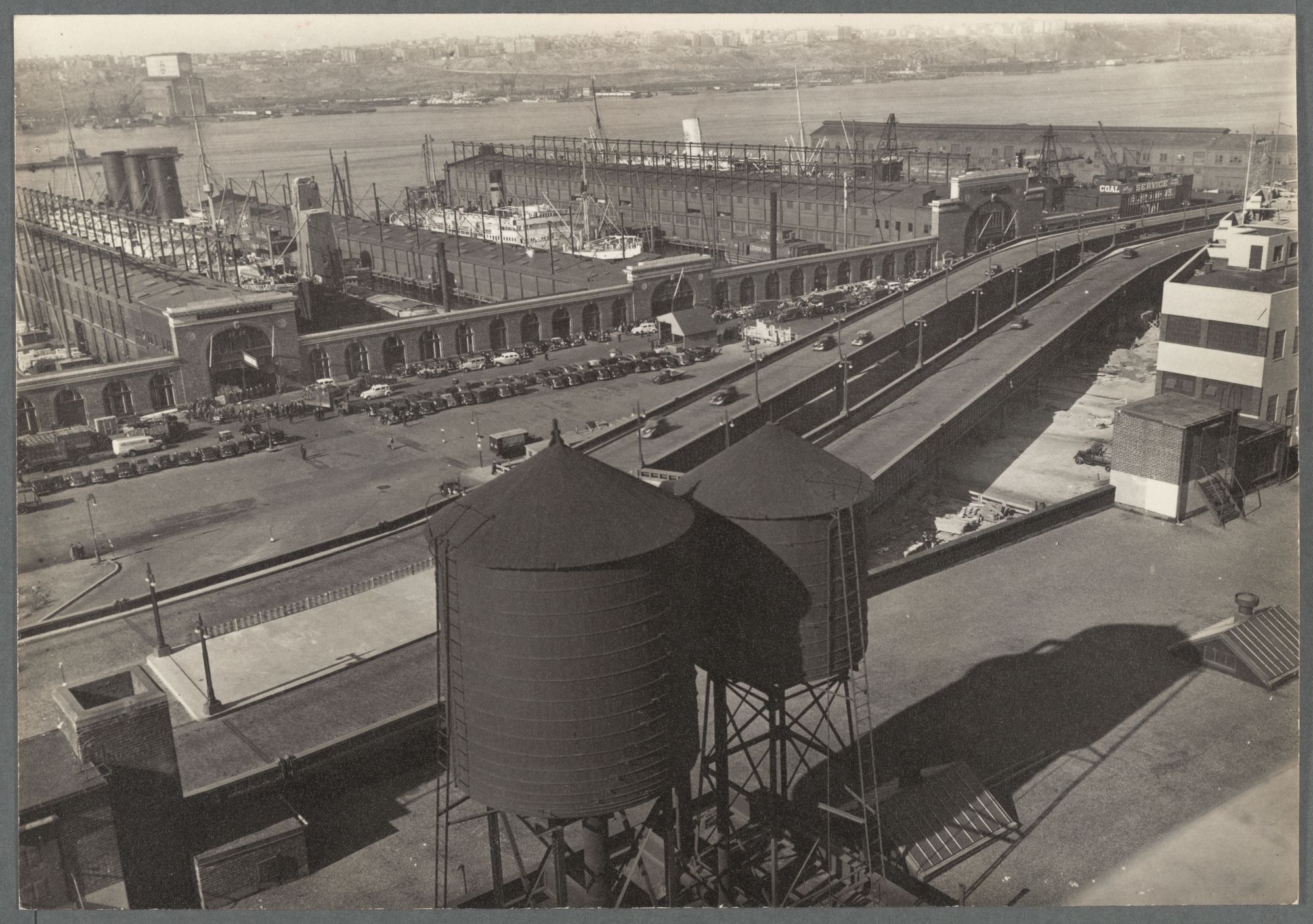

West Side Highway and Piers 95-96-97-98, Looking west from roof of 619 West 54th Street. Photo © Berenice Abbott.

Pier 34 New York. 1983. View from Hudson River. Photo © Andreas Sterzina.

Pier 34 New York, 1983. Inside the great hall. Photo © Andreas Sterzing.