NEW INC.’S SALOME ASEGA ON IMAGINING FUTURE TECHNOLOGIES AND EVERYDAY DESIGN

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

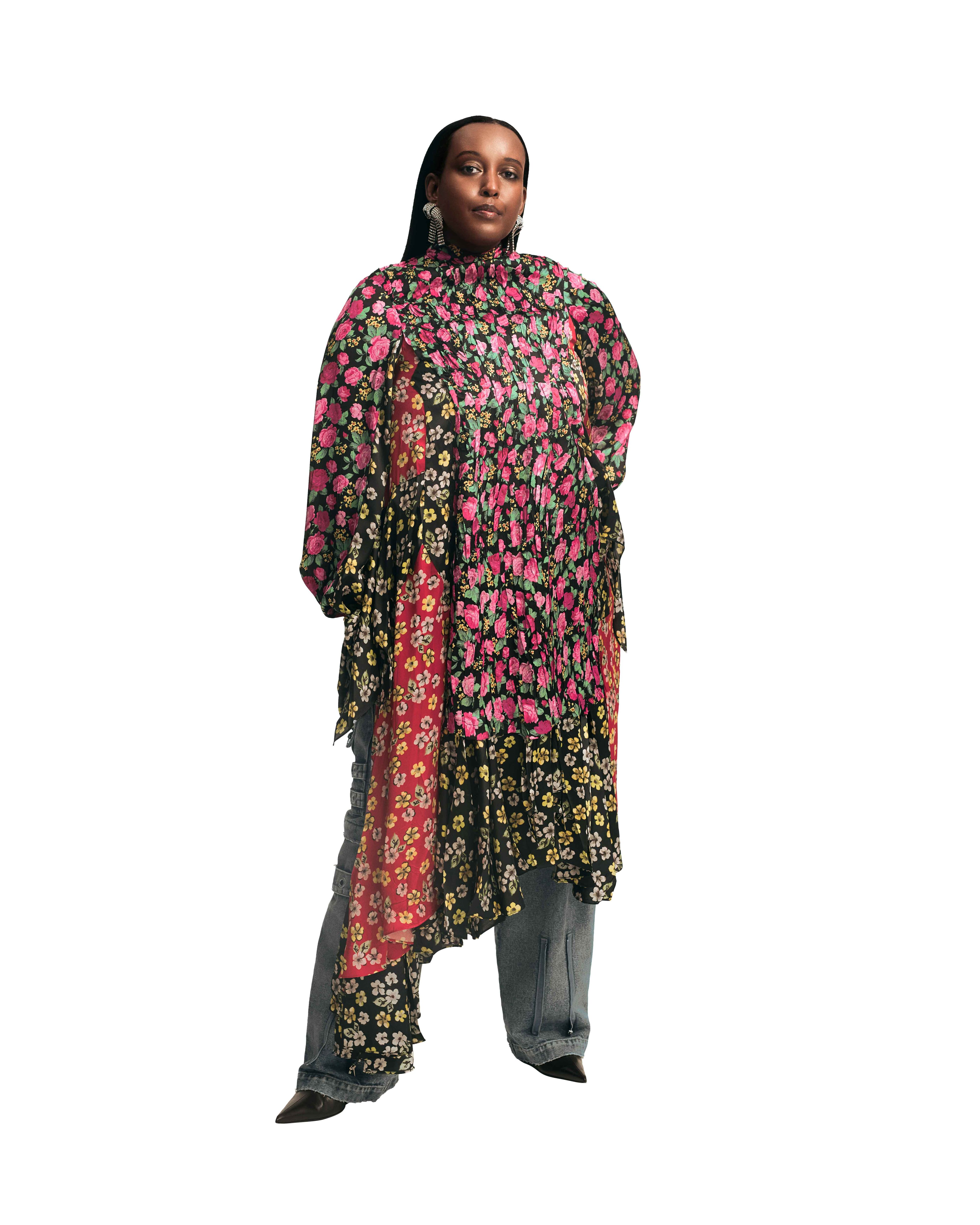

Salome Asega photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

The word visionary is thrown around a lot, but Salome Asega can bear claim to that descriptor in a way that few other people in New York’s art and design world can. Last year, she took over the helm of NEW INC., the New Museum’s incubator, which was set up to support creative entrepreneurs and professionals whose work pushes forward the nexus of art, design, and technology. In 2016, when she was a NEW INC. member herself, Asega joined the team at POWRPLNT, the Bushwick-based community space that functions as a gallery for the digital arts and an educational resource that aims to improve digital literacy — in the past, they’ve offered workshops on legal basics like licensing and starting an LLC, zine-making, and electronic-music production. Asega’s focus on education extends beyond her work with POWRPLNT, since she also teaches classes on speculative design and participatory-design models at Parsons at the New School. With her own work and in her support of others, Asega is consistently mapping out what our collective futures might look like, all the while acknowledging the limits and possibilities of the technologies that will get us there.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What is your framework for artmaking?

Salome Asega: I studied social practice at New York University’s Gallatin School, where I focused on socially engaged art and community practice. My interest in tech came the year after I graduated and spent a summer traveling Ethiopia and then later Haifa to visit a Palestinian friend who I met through campus organizing for the Palestinian Solidarity Committee at NYU. I was inspired by these two experiences, which made me want to integrate technology into my practice by connecting artist-activists across geography.

What did technology mean to you at that point in time?

[Laughs.] A website. I decided I was going to build a website that served as a social platform for artists and activists, but I didn’t know for what exactly — I just wanted everyone to be in conversation with each other. I applied to Parsons School of Design for an MFA in design and technology, but I took a hard left when I got in because I was exposed to this world of physical computing. I was mesmerized by how artists were working with software and hardware, building kinetic sculptures and using hacking techniques to make interactive experiences. I was interested in the intimacy of working with machines.

Do you think of technology as a computing architecture?

Absolutely, in the sense that architecture is a social and spatial design. Technology is a tool that also facilitates that in its own way by contributing to how we relate to each other and to space. I’m interested in building physical things that are immersive and interactive, so I started tinkering. I was mostly thinking about Amiri Baraka’s 1970 text Technology & Ethos and machines being an extension of the people who made them. It’s important to understand that technology is architectural, social, and historical. So much of how we code things is based on what has already happened. It’s important to think about what it means when a historical document is inaccurate or contains multiplicities beyond category. That’s how we entered the place where we are with A.I. We need regulation because automation is built on a historical record and the history isn’t always right or inclusive.

We understand history as a mythic story and structure for understanding the present, but falsities are being built back into the framework.

It’s funny how we’re building all of these predictive tools and technologies that can only forecast based on what has happened. And who’s doing the record keeping of what happened? It reminds me of this Kodwo Eshun quote, “It is clear that power now operates predictively as much as retrospectively. Capital continues to function through the dissimulation of the imperial archive, as it has done throughout the last century. Today, however, power also functions through the envisioning, management, and delivery of reliable futures.”

Where do you feel we are now in terms of Web 3.0, cryptocurrency, and non-fungible tokens? Do these topics cross your desk at all?

[Laughs.] Yeah, I mean people are mainly asking what happened to Web 1.0 and Web 2.0? I want to help people understand the challenges. It feels like a short history but it spans 30-plus years of known infrastructure.

We lack the language. No one knows how to talk about the Internet because we all have our own way of navigating it.

Exactly. It feels like we’re starting mid-season in a television show. Wait, what happened? Who’s that character? There’s also an architecture to the Internet that people don’t regularly address in terms of how it requires land use.

I’m so happy you’ve brought that up, because on Twitter recently people have been talking about how vast and unknown the ocean is, but to me, when I think about the ocean, the Internet immediately comes to mind. We have Internet cables connecting continents. Let’s talk about it! How do fiberoptic cables affect the sea?

[Laughs.] I know. What are the long-term impacts of this material existing in someone else’s home in another ecosystem? Who’s doing the oral history project with the people who are responsible for that?

What’s your relationship to design?

I’ve always been inspired by Xenobia Bailey, a designer, fiber artist, and Industrial Design graduate of Pratt Institute who questions the ways that design has become professionalized instead of focusing on the things that we do every day, and the quick problem-solving we do to conjure systems for comfort. Her project Paradise Under Reconstruction explores the way homemaking involves a design process for sustainable living.

What would design of the everyday mean?

You know when your mom goes to the store and takes groceries home in plastic bags that she then reuses as trash bags? That’s a microsystem in the home she has designed so she doesn’t have to buy bags. I’m focused on thinking about how we can think about that as a system of design. How can we expand on that while maintaining its design-thinking roots? There are so many things we do to problem solve and fix things in our everyday life just by acknowledging rational thinking and thinking beyond ourselves.

It’s a spatial practice. How did you recognize that as a system you wanted to engage?

I did a residency at Recess as a part of their Assembly program, which is an arts-diversion program that works with court-involved youth. The young people attend workshops with visiting artists instead of doing court-ordered time. I was doing speculative future workshops with them, and one day people couldn’t get into the zone. Someone broke the ice and was like, “Yo miss, imagination is a privilege. I don’t have time or space to think about the future. I’m just trying to get through today.”

What do you do with that response?

I shifted the conversation to address how we think about timescale in our frustration. We can’t think speculatively about 100 years from now because too much is at stake now. What I also hear from them is that they’re frustrated by the overlapping systems that have not offered them care, support, or grace. You get to this place where you’re angry that you even have to be here and have this conversation. Let’s talk about that and the things that got you here, and the ways we can fix this moving forward. It’s important to remember that the speculative often addresses and points to our current systemic challenges.

What’s at stake for you right now and the work that you do?

At NEW INC., we’re coming out of a two-year period where artists have been hit hard. My mandate is to support artists in building sustainable creative careers and to understand where creative practitioners fit into conversations around the future of workers. Another thing that feels important is that we’re living in what feels like a small window to make change when it comes to big tech in society, and I really think artists have a critical role to play in that movement organizing, because tech companies are facing immense regulatory pressure from civil society and government. There are amazing tech-policy voices who are telling us why we need more than reform and regulation, but a white paper can only go so far. I think artists have a role here: they can socialize these ideas visually and experientially. Think about it: I can send you an essay, a meme, take you to an art show, or we can watch a documentary together, and you’ll not only understand, but feel what is going on better than reading the policy paper, the white paper alone. We need translation. That’s the real work.

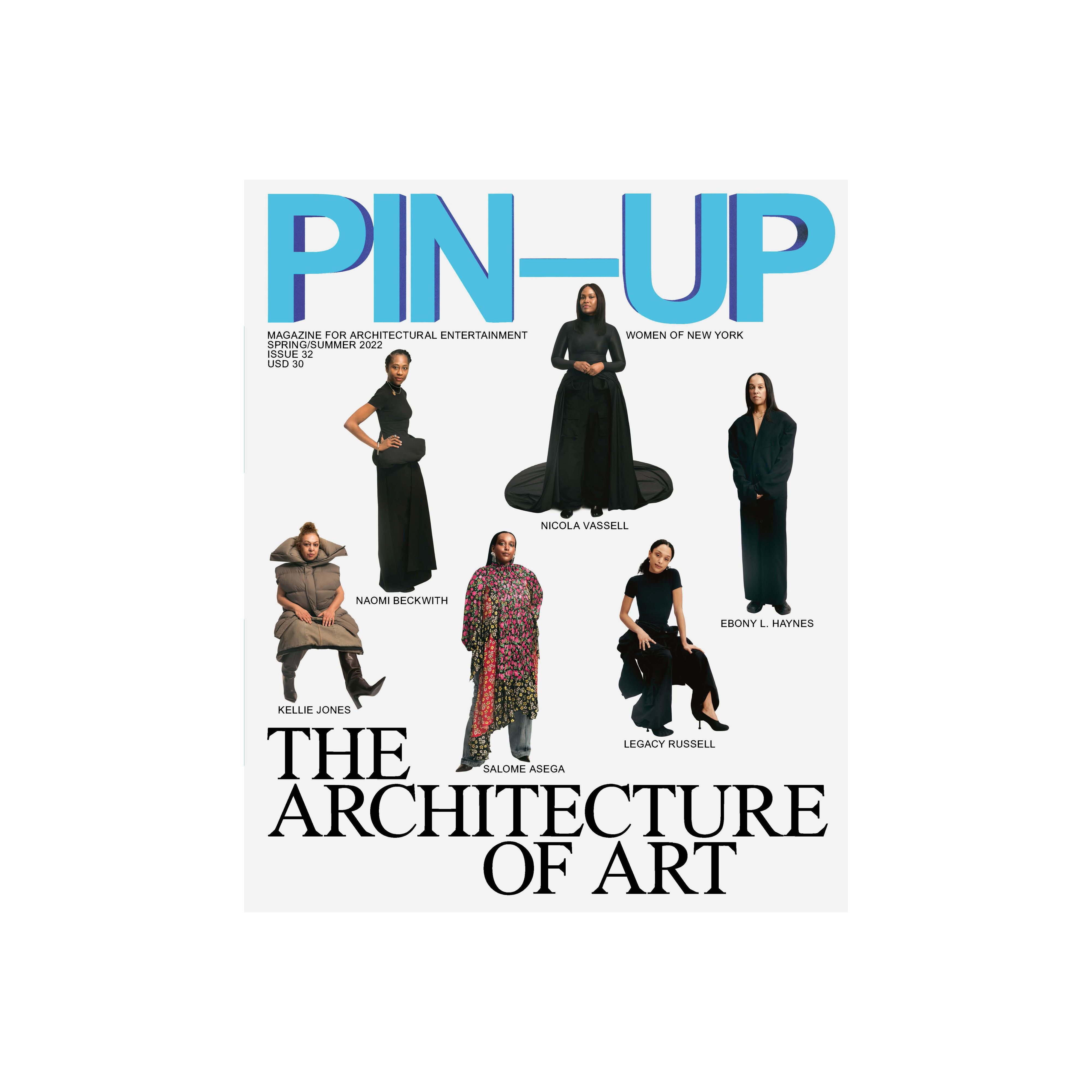

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.