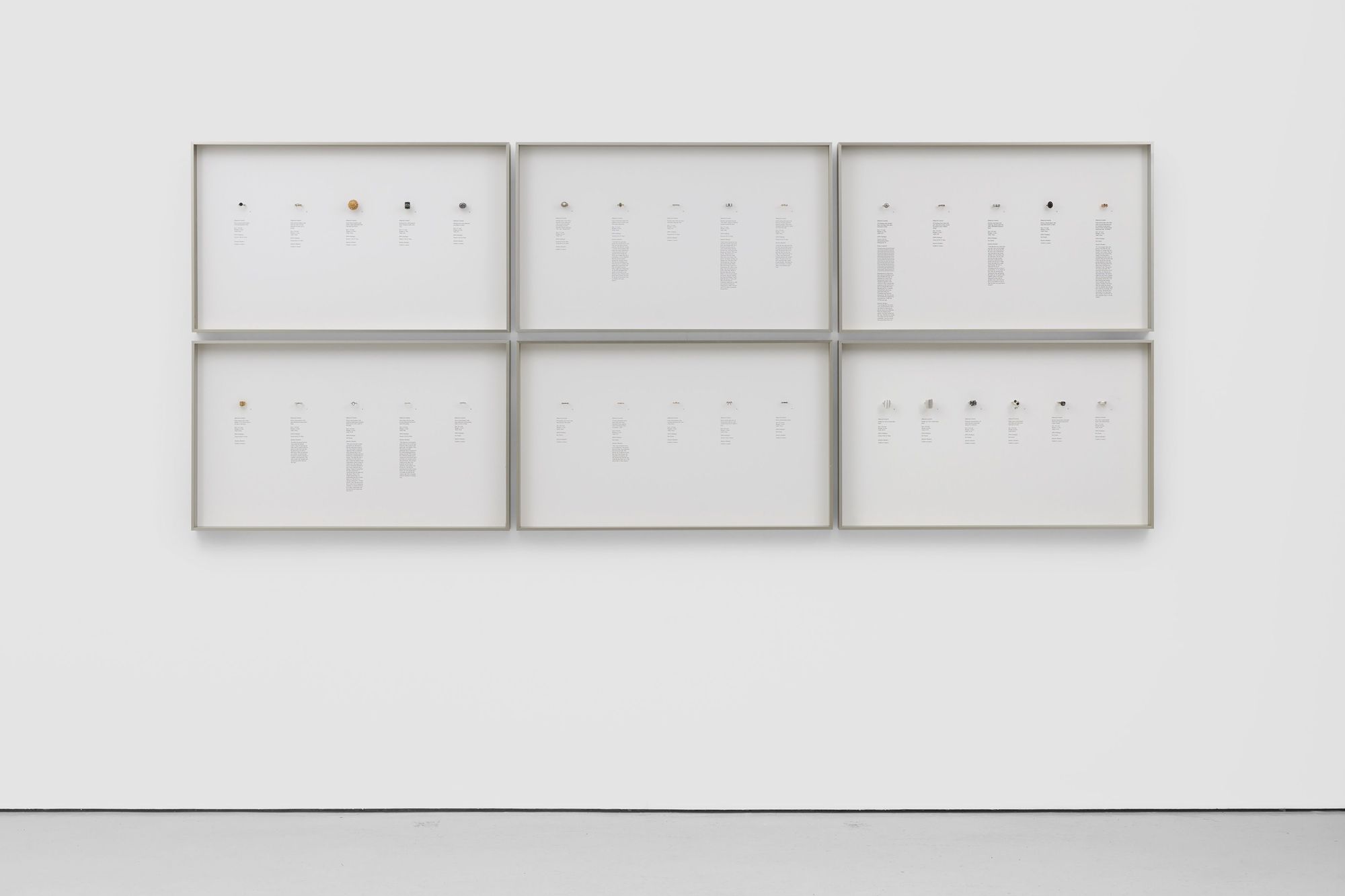

Detail view of Rose Salane’s 64,000 Attempts at Circulation (2022). Courtesy: the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photographed by: American American Art Catalogues.

In Twenty Minutes in Manhattan (North Point Press, 2009), the late architect and critic Michael Sorkin chronicled his commute from his rent-controlled West Village apartment to his office in Tribeca. His journey began at his building’s staircase and continued onto the stoop, down the block, and into Washington Square Park. Sorkin charted a personal history of New York’s architecture, using his perspective as a commuter to tell the story of a city.

It’s an approach that artist Rose Salane — a former student of Sorkin’s — reworks with objects, as she did with 64,000 Attempts at Circulation, a collection of counterfeit coins she bought at auction from the MTA piled up on the fifth floor of the Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept. “I’ve been a commuter for most of my life,” she said over Zoom recently. “Growing up and commuting from Queens, I remember from a very young age being able to see a really wide range of New York, from the perspective of the train, the bus, and through walking. In that process of movement, and in most of the work, there’s some form of a conceptual spirituality, a role as a witness.” To dissect and reflect on the infrastructure of cities, Salane reconstructs the urban landscape through items found in public spaces, or what she calls “power objects.” These collected objects include the coins mentioned above, rings lost in the MTA system, and kiosks from the now-defunct iconic department store Century 21. In a way, Salane’s artistic output is equivalent to a piece of literary auto-fiction; the objects she collects are not her own, but they are pieces of a wider civic fabric that she is a part of. And while her scope is not limited to New York — neither was Sorkin’s — her work possesses an acute awareness of the nuances of the city she calls home.

Salane completed her BFA at Cooper Union before undertaking an MA in Urban Planning at the Bernard & Anne Spitzer School of Architecture, CUNY. Spearheaded by Sorkin, the program revolved around his belief that urban design was a tool of enlightened social engineering and power sharing. Salane enrolled in this program specifically to write about the technological changes of the early 2000s in New York that redefined public versus private space. As someone who grew up in that period, Salane identified a persistent anxiety in her peers and society at large brought on by questions of public safety following 9/11. “Safety is at a lot of people’s expense — it is meant for a certain group and everyone else is thrown under the bus,” she says. This pronounced surveillance of public space and the creeping of government authorities into private life urged her to question the underlying logic at play. Whose lives should be saved? Who is made to feel safe in public? And at the expense of who else?

Detail view of Rose Salane’s 64,000 Attempts at Circulation (2022). Courtesy: the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photographed by: American American Art Catalogues.

“Slugs,” or the counterfeit currencies used to trick the coin-operated devices on New York City buses. Detail of Rose Salane’s 64,000 Attempts at Circulation (2022). Courtesy: the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photographed by: American American Art Catalogues.

While this research project is on pause academically, it has deeply informed Salane’s artistic practice. One of the perks of the Graduate Center was that Salane had access to information beyond Sorkin’s class. Training through courses on sociology, geographic information studies, ethnography, etc., taught her to use urban studies to understand the structural backbone of cities. Sorkin argued that architecture exists at the intersection of art and property, which is why it so effectively records the history of communal life. But when architectural thinking is infused with a certain sense of poetics, there is the potential to move back to art and consider urban life on a human scale. Salane’s work exemplifies this approach in that it takes forgotten, lost, and discarded objects and contextualizes them with new meaning, asking vital questions about cities and those who inhabit them through a long-term process of collecting urban detritus. “I’m interested in how movement through an urban environment can appear through residual objects, and I make this knowledge available for people.”

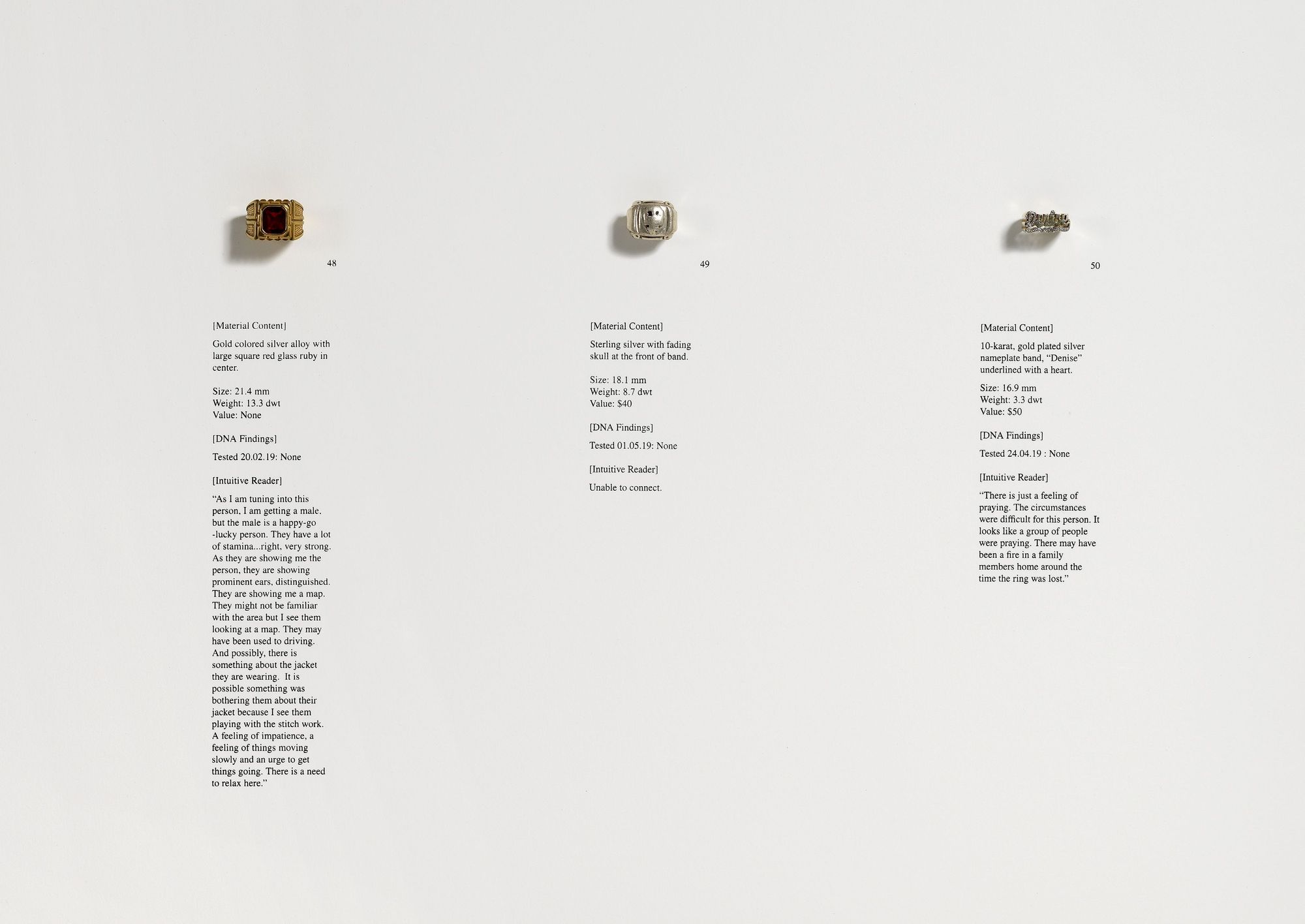

In Panorama 94 (2019), produced for Salane’s solo booth in the Art Basel 2019 Statements sector, Salane presented a collection of 94 rings that were lost throughout the New York City Subway system in 2016. The MTA identifies their color and material before tagging them with a unique number for their records, allowing their respective owners to reclaim their lost property for one year before putting them to auction. Salane acquired the rings at auction, and she built on the MTA’s documentation system with her own cataloging system that speculates on the lives of their owners. Salane worked with a biology lab to extract potential traces of mitochondrial DNA left behind on each ring, an intuitive reader to search for any spiritual information imbued within these objects, and a pawnshop to appraise their material values. Presented alongside the rings themselves, these inquiries put the relationship between fact and fiction into flux, pointing to the latent potential in objects to serve as sites of memory and repositories for specific moments in time.

She further explored these ideas in her exhibition Indigo 237 (2018), held at Company Gallery and hosted by Carlos/Ishikawa during Condo New York. Created in collaboration with Deborah Rodi, the exhibition resulted from an ongoing dialogue in which Rodi shared her experiences as a hostess at Windows on the World, the restaurant formerly located on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center North Tower. Structured around a series of five texts written by Salane in consultation with Rodi, the work follows a chronology that grounds Rodi’s narrative testimony with physical objects from the site — playing cards, business cards, a silver cigar cutter. By collaging an oral history with physical anchors to a historical period, Salane uses these objects as portals to discuss the nuances of the urban symbolism and realities of a pre-9/11 World Trade Center in a post-9/11 world. Beyond the site’s infamous tragedy in 2001, the World Trade Center previously stood as a symbol of global corporate modernity and economic growth that hinged on an ever-expanding, low-paid service economy. Workers like Rodi experienced first-hand the widening wealth gaps in the American economy, greater social inequality, dramatic increases in crime and drug use, and the AIDS epidemic. In this instance, Salane acted as a mediator for Rodi as a historical witness of New York.

Rings lost in the New York City subway, from Rose Salane’s Panorama 94 (2019). Courtesy: the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa, London.

Rings lost in the New York subway, from Rose Salane’s Panorama 94 (2019). Courtesy: the artist; Carlos/Ishikawa, London.

Salane’s most recent project at the Whitney Biennial relies on a sense of anonymity in the same manner as Panorama 94. In 2019, Salane acquired 64,000 coins from an MTA auction collected by the city from 2017-19. Referred to by the agency as “slugs,” they are counterfeit currencies that were used to trick the coin-operated devices on the city buses. Salane has spent the last several years meticulously sifting through this collection to group them into five categories — faith, place, chance, imitation, and blank. For their presentation at the Whitney, she has decided to show the coins in large piles based on their categories rather than lay them out individually. Her interest in this idea of a mass stems from her curiosity about the 2003 blackout that disrupted the northeast. Across the region, but in New York City specifically, helicopter news footage tracked people’s responses to moving through an infrastructure without power. In the absence of electricity, they gained more access to a sense of civic control over public space. For some, this meant a night spent walking over the Brooklyn Bridge next to the FDR; for others, the streets became a place to party; elsewhere, in the heat of summer, it was chaos.

Even across these varied experiences, there was a shared constant of movement across the city. There was a similar bubbling of mass and movement in the summer of 2020, when the waves of protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and weeks of fireworks blaring across the city broke the silence of the first period of pandemic lockdowns. While the collection of coins is pulled from a specific time period, in Salane’s hands, they become tools to address site-specificity versus universality. They present a discrete slice of history to tell a broader story: one that illuminates the identity of a city and its people through its forgotten and discarded objets.