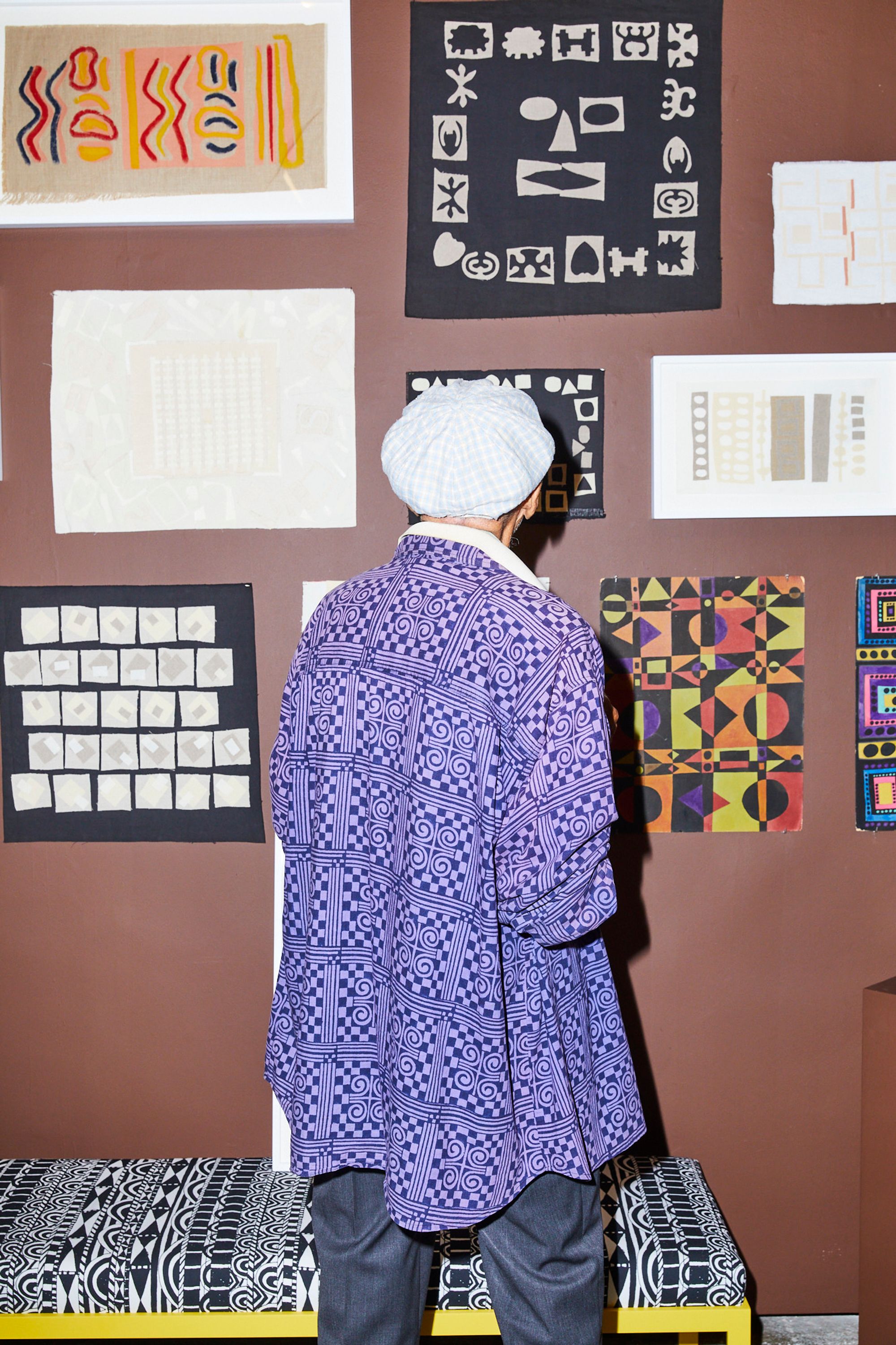

Robert Paige photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP 33.

Robert Paige photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP 33.

Robert Earl Paige just about single-handedly brought West African-inspired patterns into the hands of U.S. shoppers in the 1970s with his Senegal-inspired Dakkabar collection. Stocked in 120 Sears, Roebuck & Co. stores in 56 cities across the country, the textile designer’s brightly patterned pillows, bedspreads, and draperies spoke to his desire to offer Black homemakers products they could relate to directly, a weaving of his politics into something as everyday as a set of curtains. Almost 50 years later, Paige credits his keen interest in color as a counterpoint to the gray winters of his Chicago hometown and the aesthetic heritage of its Black community. An alumnus of the interior-design department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Paige was part of both the Black Arts Movement, which was hailed as the artistic arm of the Black Power Movement, and the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), a Chicago-based group of Black artists who looked to Africa as an essential reference for the African-American community. This year, Robert Earl Paige: Power to the People, an exhibition curated at New York’s Salon94 by fashion designer Duro Olowu, set forth a total vision of the 86-year-old’s practice — as well as his textiles, it showcased his ceramics, collages, and etchings in a rich and varied oeuvre inspired by everything from Southern shotgun houses to the Bauhaus. Even though Paige considers himself a ghost artist because so much of his work went uncredited, the Salon94 show has now changed the historical record — it is no longer possible not to see Paige’s enormous influence on American design.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: Did you feel that the Civil Rights movement was misrepresented in the press?

Robert Earl Paige: We were so engrossed in our camaraderie and common interests that we didn’t pay attention to how people were categorizing us. In my community, we had the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, the Afro-Arts Theater, and different event venues all over the South Side. But everyone also had their passports in their pockets, because we didn’t trust shit and we didn’t know which way things were going to go. If you think about Malcolm X and Medgar Evers, these cats didn’t live to be 40 years old, so shit was treacherous, but everyone kept pushing along. We were following the work. We weren’t working in reaction to anything — we were working to have fun. We were an aesthetic moment and it was important that we were doing what we did, which is what I call my assignment. My art is my assignment in life — I’m working in the pursuit of beauty.

Robert Paige photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP 33.

Robert Paige photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP 33.

How do you feel about the narrative that’s been ascribed to the Black Arts Movement?

It’s kind of like with the Harlem Renaissance — it wasn’t a name we chose but one that was given to us. If there was a Black Arts Movement, it’s not dead because we are still alive doing what we’re doing. We didn’t think of ourselves as a movement — as I called it, we were a new visual order.

What motivated you when you were younger?

I was thinking about fun and exploring. I was just walking through the world trying to enjoy myself. My mom would say, “Bobby, stop picking up stuff off the ground and putting it in your drawer.” I didn’t realize that I was hooked on Marcel Duchamp’s idea of readymades. [Laughs.] I’m a doodler, tinker, and dabbler. When you’re doodling, your unconscious is creating something. But when you look and see something you’re hooked on, it ruins the flow because your conscious mind has kicked in. My only conscious desire is to develop, experiment, and arrive at something that gives not only me, but also the viewer, pleasure.

Robert Paige photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP 33.

So how did you go from being this free spirit to an intentional designer?

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. That was invaluable in terms of putting me in a position to see, learn, and explore. I started there when I was 25 years old. I worked in specification, where you made changes or edits for all the different departments. Charlie Duster was in mechanical and air conditioning. There was Don Ryder, who designed the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem with J. Max Bond Jr. Being around these people just opened up a whole can of worms for me in terms of possibilities. Bill Morrison was in the design department. I kept telling him that I was going to enroll at the Art Institute of Chicago, and he told me to shut up. He told me to tell him when I’d enrolled, which shut my mouth and then I ended up at the Institute anyway. [Laughs.] I was at SOM for over ten years. I left when I was around 30. That's when I started designing for the Italian manufacturers in Milan.

What are your thoughts on design and architecture?

I used to think about home fashions and interiors, but now I am more of an artist who uses textiles as my medium. When I’m doing something, I’m just trying to get the best colors and patterns out of me, and make sure it adheres to certain principles and philosophies that relate to simplicity as its own best design. The idea that a line is never ending, or as Paul Klee says, “a line is a dot that went on a walk.” These are all things I use for inspiration, which only occurs when you get rid of the clutter, doubts, shame, and fear. If you strike out all of those, then you have a chance of making something for the sake of pure creativity, but that takes a lot of courage. And that’s the thing that kept me going — I got courage. It’s about having consistency, commitment, confidence, courage, and curiosity.

When you doubted yourself, what was your anchor?

Here’s an example. The Dakkabar collection was in 120 stores in 56 cities. I flew from California to the Big Apple, and I got to the hotel but I was supposed to be on the radio program at eight o’clock. And I’m lying on the bed exhausted. I said to myself, “There were times when you didn’t have shit to do, and you’re thinking about not going to the show and missing your assignment.” You know, I’ve never missed a plane. If I tell you I’m meeting you somewhere, then I’ll be there. If you’re not early, then you’re late.