Dana Arbib, Roccia, 2022. Image by Matthew Gordon. Courtesy Matthew Gordon and Dana Arbib.

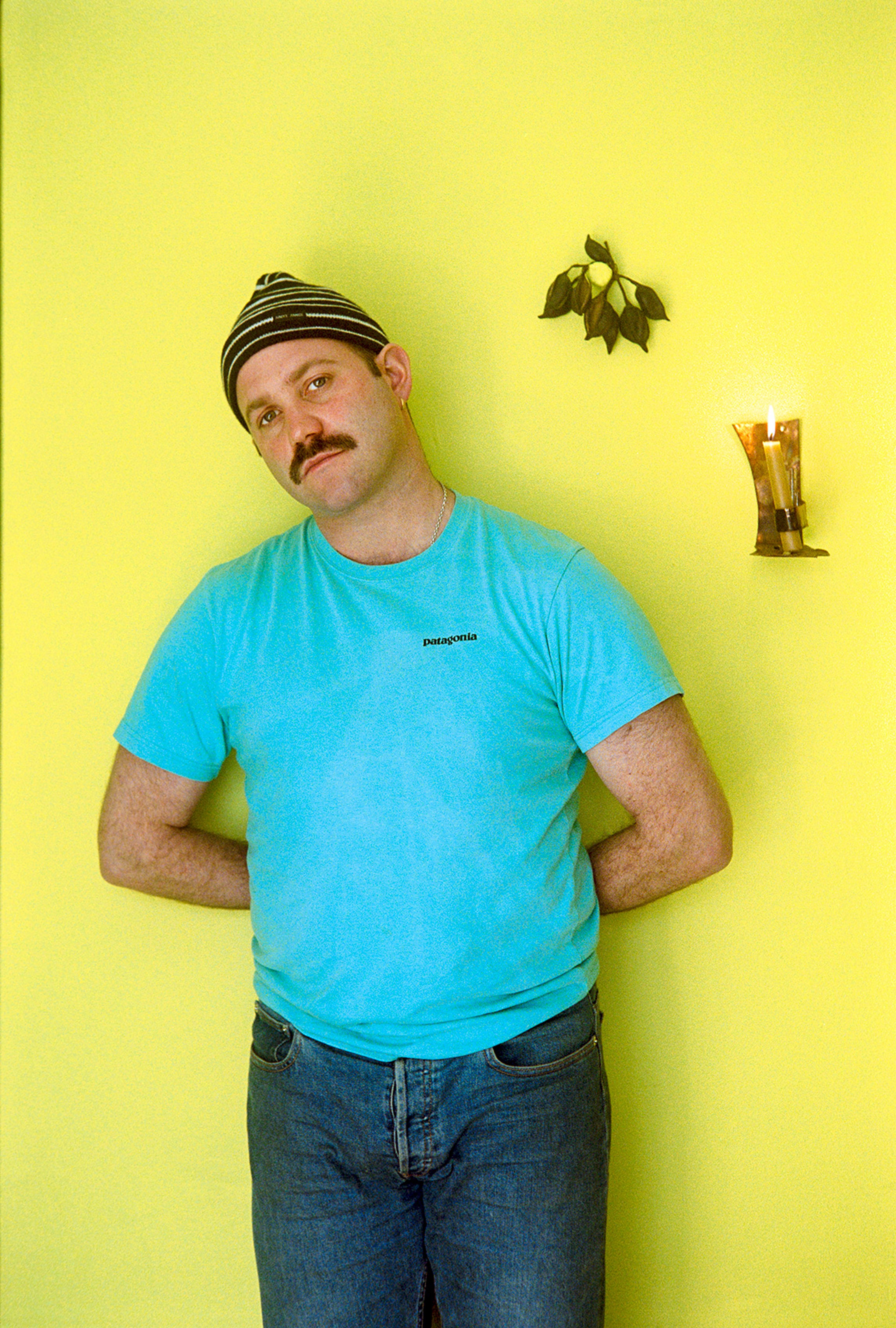

The design gallerist, collector, and entrepreneur Alex Tieghi-Walker in his Gramercy Park studio in New York City. Photographed by Thomas Dozol for PIN–UP.

The perennially smiling British bear Alex Tieghi-Walker grew up on the coast of South Wales. A love of the handmade was instilled in him from an early age by both his maternal grandmother, who made colorful quilts from fabric she sourced from travels around the world, and his Venice-born father, who is a printmaker, photographer, ceramicist, and sometime puppet creator. After studying literature in London, Tieghi-Walker worked for the video platform Nowness, but love eventually brought him to the Bay Area, where he freelanced as a journalist while also creative directing in tech-adjacent industries. Along the way, he founded The Anonymous Sex Journal, an illustrated anthology of his friends’ erotic exploits. Tieghi-Walker always maintained a connection to his family’s artisan roots, experimenting with his home as an exhibition space for local craft, hosting friends for meals and parties as he shared his latest design-art-craft discoveries, first in his Berkeley apartment, and later in Los Angeles at his house in Echo Park. In summer 2021, he formalized this activity, launching Tiwa Select, a platform that straddles the lines between gallery, shop, agency, media outlet, and production management. A self-taught gallerist, Tieghi-Walker is drawn to auto-didact artisans, figuring out his own way to support them. Combining his gregarious charm and love of entertaining with his skill for storytelling, he effortlessly connects his makers with his circle of influential friends and clients, introducing them to wood-work by Vince Skelly, face-jug ceramics by Jim McDowell, or seaweed-inspired glass-ware by Dana Arbib, to give just three examples. In spring 2023, Tieghi-Walker began a new chapter of his life in New York, establishing Tiwa Select at the historic National Arts Club on Gramercy Park.

Michael Bullock: I just re-watched the video Vogue filmed at your beautiful Los Angeles home in 2021. You were living the L.A. dream. Why did you leave?

Alex Thieghi-Walker: I know. It was bittersweet. It was such a gorgeous moment. It was less about leaving my house and more about leaving L.A. After having had very hedonistic teens and 20s in London, I escaped to California. I felt that moving somewhere small and sweet like Berkeley would be a good reset. It was never my intention to move to L.A., but my boyfriend at the time was living there and he managed to twist my arm. Geographically, L.A. reminds me of Wales, where I’m from. Wales is gorgeous, and it has a history of environmental activists, artisans, and communes, so I was very much drawn to California because of that. At the same time there were drawbacks. I felt isolated from Europe. I felt behind on news. I felt like the whole world lived a day before we woke up. L.A. is so big and spread out that people in L.A. are such homebodies. After four years in California, I was craving a faster pace of life. When my boyfriend and I broke up, I hung about in L.A. for another year and a half.

Alex Thieghi Walker in his Gramercy Park studio in New York City. Photographed by Thomas Dozol for PIN–UP 34.

And then New York called?

Last summer, I was like, “You know what? I’m 35. Now’s my time to go to New York. I’m still young enough to be able to deal with hangovers. I’m still young enough to be able to make new friends. I want to be pushed a bit more...” L.A.’s a very creative city, but in New York there’s so much more. Every Thursday there’s 20 fucking openings. I’m not good at complacency. What I find really enjoyable about life is being forced to think a different way because you have to. Moving to New York has been an insane challenge in every sense of the word.

What’s one of the biggest differences?

People consume things in a different way here — they’re a bit more considerate about what they put into their space, because they have less of it.

Your first flirtation with organizing exhibitions was in your apartment in Berkeley. Can you describe it for me?

That building felt like an upside-down boat, it had very good energy. It started off as a home and I slowly started filling it with things that I collected. And then I started hosting events. People would come in and ask, “What’s this? Is this where you live? Is this an art gallery?” I started thinking about it more as a pub-lic space than a home, an idea I carried through. In the L.A. house, I would forget to write down appointments, I’d be in my underwear reading the newspaper and suddenly a couple would be in the living room and I’d have to scurry off to get dressed and pretend I’d been expecting them the whole time. Now that I’m in New York, I have no interest in combining private and public. I want to keep my house very much my house and this very much the gallery. I’m enjoying the separation for now.

Vince Skelly, from left to right: Chair #2 (deodar cedar), Dolmen Table (cedar and pine), Stool #1 (liquid amber), and Chair #1 (deodar cedar), 2022. Images by Raymond Molinar. Courtesy Raymond Molinar and Tiwa Select, 2022.

You studied literature and worked as a journalist, which is great training for a dealer. After all, objects are just things unless you connect to their story.

Some curators and collectors are very drawn to the aesthetics of a piece. I’m so drawn to the journey that brought the artists or makers to where they are. I like to lead with the story of the maker, but also the story of the material. The show I organized of Vince Skelly’s wood sculptures in downtown L.A. was called After the Storm. There had been this severe storm in Claremont, with gusts of over 83 mph. It blew for six hours and brought down over 300 trees. Vince managed to salvage the most amazing woods. I just thought it’d be really beautiful to capture the energy of the storm, showing where the material had come from. We gave five percent of the sales back to the city of Claremont to replant some of the trees as a thank you for providing us with the lumber.

Why do you think that show resonated with people?

Vince’s work is soulful and authentic. He’s not coming at it with any institutional pretense. His show was designed to be as interactive as possible. I’m never precious about any of the art I’m working with. With Vince’s show, I’d invite people to visit when the sun would be pouring horizontally through the windows, because the works caught the light and you’d see these amazing shadows that the pieces threw on the walls. The beauty of wood is its texture and the way it catches light, so it really brought out the way Vince carved each piece.

The design gallerist, collector, and entrepreneur Alex Tieghi-Walker in his Gramercy Park studio in New York City. Photographed by Thomas Dozol for PIN–UP.

This last couple of years, smaller independent design platforms with strong Instagram followings — like yours — have managed to have a big impact on the broader design conversation and where tastes and aesthetics are headed. What’s your take on this phenomenon?

Instagram has been an amazing platform simply to build awareness beyond the city that you’re based in. It puts you on the same plane as organizations that have 20 employees and 5,000 square feet. It’s a cliché to say this, but it’s such a good way to connect with people, especially if you keep your Instagram very personal. I never separated my business and my personal Instagram and I never will. That’s because the values of my business are my personal values. But also, my business itself is a story. In some respects, my Instagram is like a modern version of a blog. I’m doing something I’m passionate about and I want people to see that. That’s why a couple of times a month I present the stories of artists who I work with and their processes. I loved when Dana Arbib was working in Venice. I asked her to film everything on her phone and send me the videos each day. Instagram is so many different things in one place. It’s a brand manifesto. It’s a way for people to see the process. And it’s a way for people to read stories and learn more about different artists.

Dana Arbib, Roccia, 2022. Image by Matthew Gordon. Courtesy Matthew Gordon and Dana Arbib.

Dana Arbib, Pezzi, 2022. Image by Matthew Gordon. Courtesy Matthew Gordon and Dana Arbib.

How do you find artists and artisans you want to work with? How did you come to collaborate with Jim McDowell, for example?

What’s nice about being a non-American living in America is that I get excited about things that might seem ordinary to Americans. In California, inspired by the whole studio-pottery movement, I did a lot of research into American ceramic movements. And then I started investigating face jugs, which was an art form I’d never heard of before. It has a somewhat nebulous history — one widely understood origin is West Africa. In America, the face-jug tradition was continued in the South. Often they use these sorts of vessels to commemorate ancestors. I posted about it on Instagram and someone recommended I check out Jim McDowell. They said he was one of the few Black artists making face jugs today. So I looked him up on Etsy, bought one of his jugs and sent him a message saying, “I’m really interested in your story.” He and his wife got on the phone with me and admitted that they thought I was a scammer. I convinced him that I found his work really beautiful and that I wanted to help bring it to a wider audience. So I drove across country to visit him.

Jim McDowell, The Mother of Civilization. Image by Lenard Smith. Courtesy of Lenard Smith and Tiwa Select, 2022.

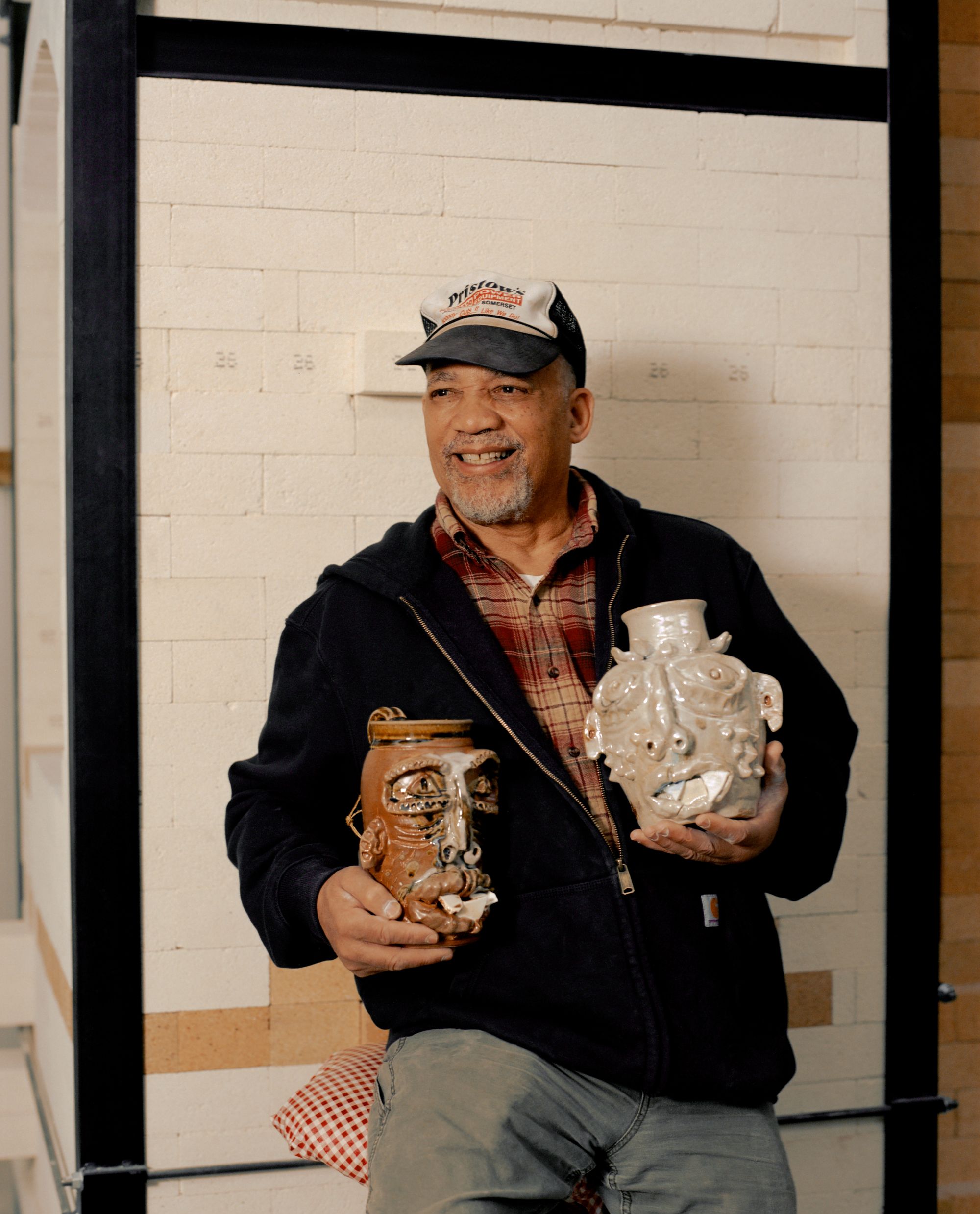

Jim McDowell in his Ashville studio. Image by PeytonFulford. Courtesy of Peyton Fulfordand Tiwa Select, 2022.

Jim McDowell, Angel Watchin' Over Me. Image by Lenard Smith. Courtesy of Lenard Smith and Tiwa Select, 2022.

Where does he live?

Asheville, North Carolina — a hippie, creative little town. I spent a weekend with him and his wife. Jim does all the cooking. We had the most amazing food. He showed me his kilns, all his pieces. He’s been making face jugs for about 15 years.

How old is he now?

He’s 77. He was stationed in Germany and then he was a miner. And then he started making pots as a way to deal with PTSD, putting his energy, anger, and frustration into ceramics. He looks at different elements of Black history, from slavery to Black agriculture to the civil-rights movement — he puts all of that history into his face jugs. I’m currently working on book about his work with writer Camille Okhio and on a short documentary with filmmaker Dwayne LeBlanc… I’m really interested in art forms or design forms that get forgotten or turned into something else. For example, stained glass, which was so beautiful historically, and then somehow took a nose-dive in the middle of the 20th century. Zachary White is a trained and accomplished architect, whose grandfather was a Dutch stained-glass artist. During the pandemic he found his grandfather’s kiln, brought it back to life, and has been making works. I like people who are whimsical and playful in the way they explore materials and materiality.

Jim McDowell, Brotherhood. Image by Lenard Smith. Courtesy of Lenard Smith and Tiwa Select, 2022.

Jim McDowell, For Dr. Mae. Image by Lenard Smith. Courtesy of Lenard Smith and Tiwa Select, 2022.

You mentioned that the values of your business are the same as your personal values. How would you define those values?

One is the environmental impact of design. My gallery is mostly design or functional-artwork focused, and I think there’s something so charming about collecting things that are specific to a place, or an individual, and are made of carefully considered materials. Ninety percent of the artists I work with source their materials from scraps or objects they upcycle or repurpose. I try to not do anything in my life that doesn’t have a level of intent. None of the artists I work with are simply making just for the sake of it. I think they’re often making work as part of a healing process in their lives, or as part of an exploratory moment, or trying to reconnect with a familial element in their lives.

Now that you’re located in the historic National Arts Club, what does the future hold?

I don’t know what shape Tiwa Select will take in the future. I go with the mood. Right now I’m happy to have an intimate space that allows me to get to know people, in addition to creating larger one-off exhibitions and experiences that create an atmosphere that’s specific to the artist and their work. This room is still so echoey. I need to do something about it. So will my next exhibition be a textile show that helps fix that? We’ll see…

The design gallerist, collector, and entrepreneur Alex Tieghi-Walker in his Gramercy Park studio in New York City. Photographed by Thomas Dozol for PIN–UP.