Maison de poupée (Audrey Tautou), 2009 ©️ Pierre et Gilles. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

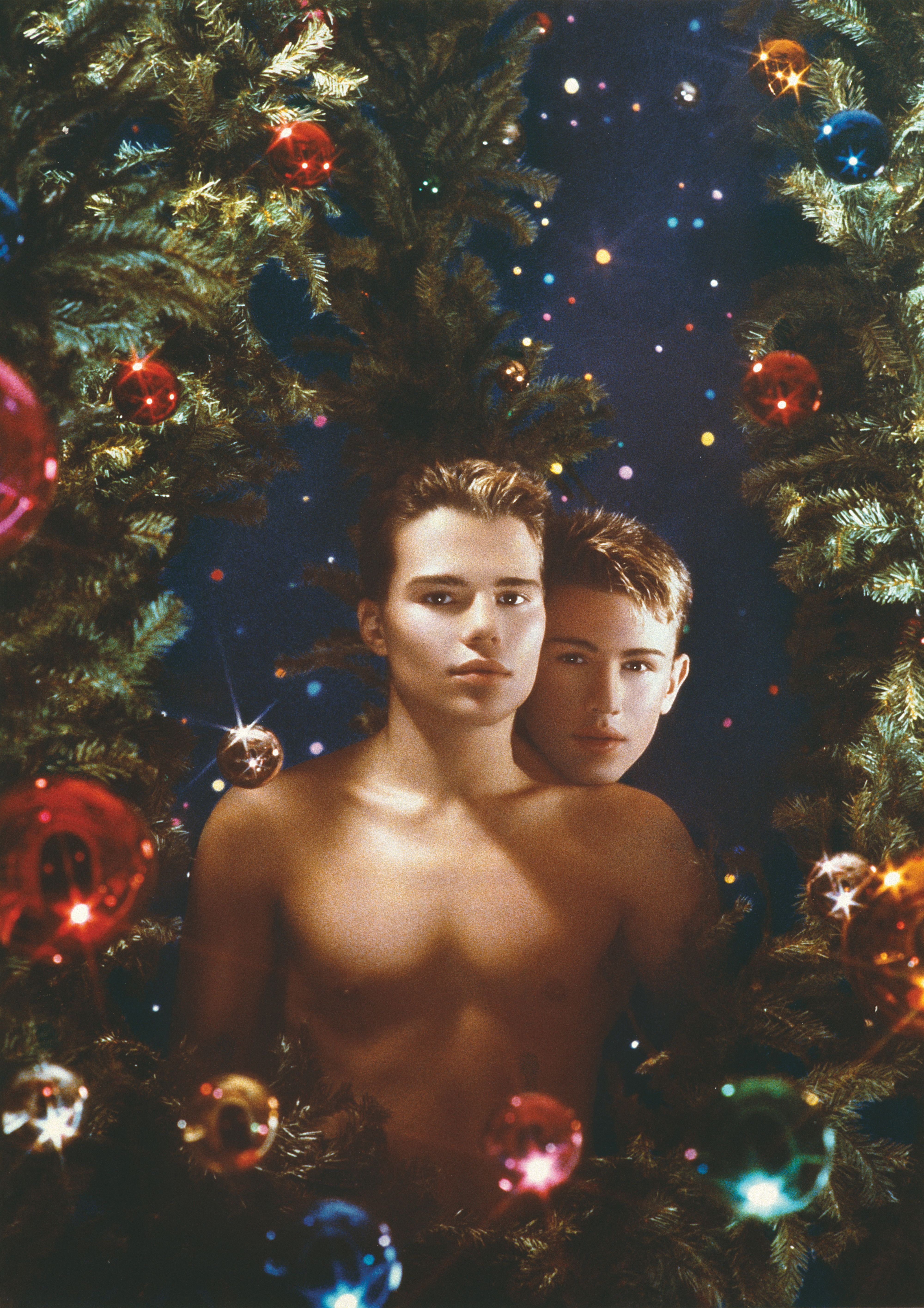

Les boules de Noël (Serge et Jean Chris), 1986 ©️ Pierre et Gilles. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Like most true visionaries, Pierre Commoy and Gilles Blanchard live in a world of their design — and they’re staying there. Since 1976, the French artist duo better known as Pierre et Gilles has created photographs that defy two-dimensionality, featuring hand-painted and assembled sets that bring out a symbolically charged glamour in subjects ranging from artists and models to actors, nightlife personalities, and athletes. But no matter who’s in front of the camera, Pierre et Gilles’s three-dimensional world building remains true to their aesthetic values. All manually produced in their home-cum-studio in Paris, the Pierre et Gilles sets are a mix of couture and DIY craft, equal parts James Bidgood queer fantasia, religious and folkloric iconography, and a sort of comic-book aesthetic in the style of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. In a Pierre et Gilles image, you might not always know where you are, but you know you want to linger there. On a recent — and rare — visit to New York, the pair lingered with PIN–UP over coffee to talk about making clouds out of cotton, Christmas decorations, and how to live in the work you make forever.

Maison de poupée (Audrey Tautou), 2009 ©️ Pierre et Gilles. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

La vierge à l’enfant (Hafsia Herzi et Loric) 2009 ©️ Pierre et Gilles. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Jesse Dorris: You exclusively shoot in your own home and studio, where you build all your sets. Why?

Pierre Commoy: Home is where I feel comfortable playing with lighting. I’m very interested in the way you light your subject, and I'm not very keen on the traditional ways that lights fall on the faces of models. To experiment it was easiest to be in my home. Originally, we also had a very small apartment, so it was mostly close-up portraits and the sets were simple. It was just one simple curtain, or just a painted backdrop of the sky. Over the years the sets got more complex. Now there are several planes on which we can hang different accessories — layer after layer. And we no longer do painted backgrounds. When we do a sky, it’s cotton glued onto a tulle veil. We light them, and they become clouds.

Gilles Blanchard: Sometimes, we may start with a very blue sky, and after a couple of hours we realize we want something darker. We can very quickly change it, just by ourselves.

How has your apartment slash studio evolved over the years?

GB: We had three apartments: a tiny one, a small one, then a large one, where we are now.

PC: In the tiny one, we used very simple lights based on a flash technique. We didn’t have much equipment. We were very poor, so it was a financial constraint but also an aesthetic one. Helmut Newton was a great reference for us at the time. He used a very minimal technique to organize his photoshoots. It became an asset, in a way.

Can you describe how the space is structured?

PC: It’s really big — an old factory on the outskirts of Paris. We completely refurbished it. For years, we worked and lived in renovations, in gravel and concrete. But over time we built something that has many different atmospheres. The rooms are influenced by our travels all around the world — one room has Indian influences, another has Chinese influences, another is covered in mosaics. We used to do everything in the same space, but now it’s more organized. There’s a space on the ground floor where we live, and below is a studio and workshop, as well as storage for all the accessories. And Gilles has his special room where he paints, a greenhouse inside a room. It’s not about light but an enclosed space where he feels safe. Gilles is a delicate flower. [Laughs.]

GB: It’s actually for protection from dust! I use an airbrush, and the dust gets everywhere.

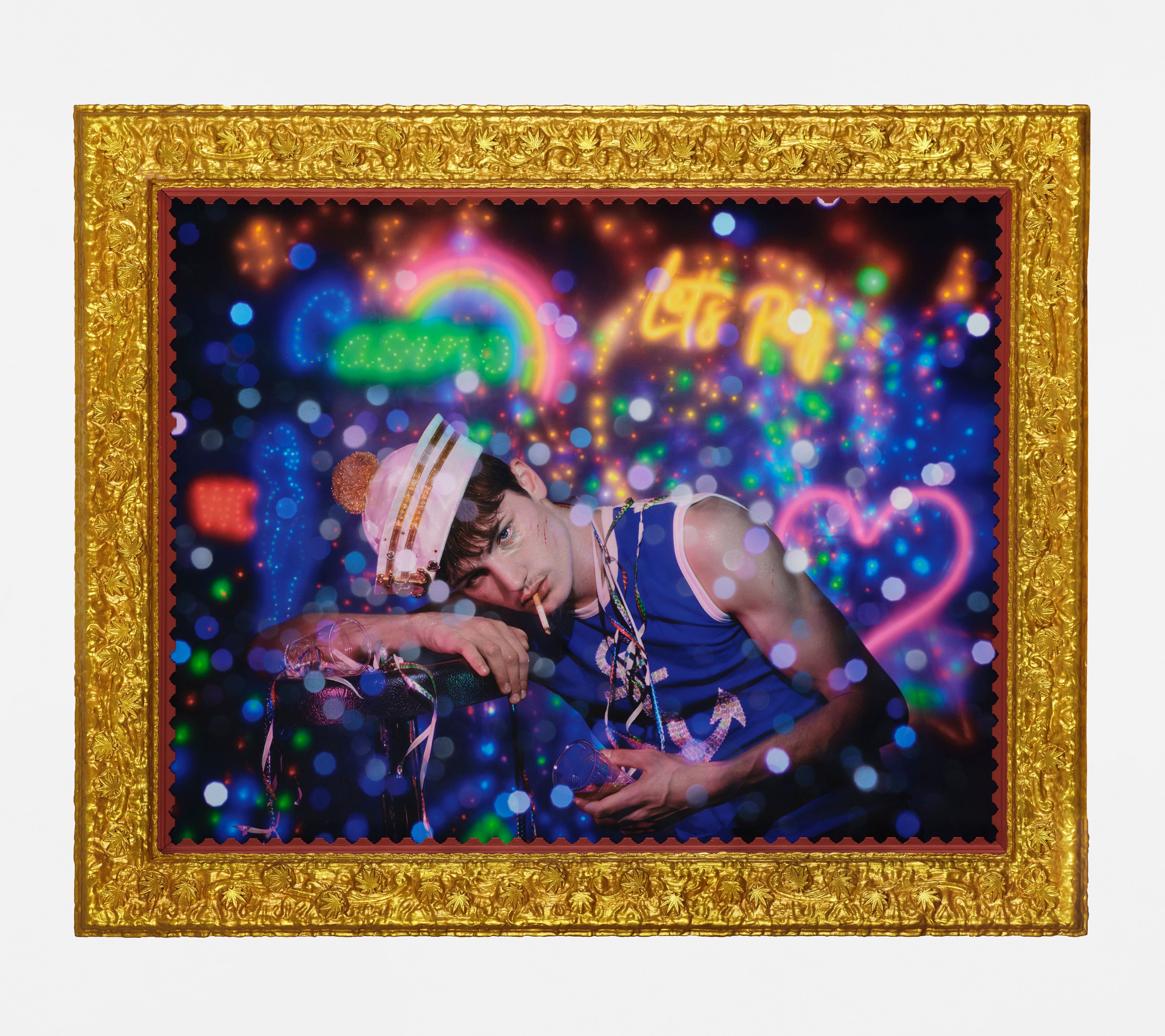

Let's Party (Antoine Rigolot), 2023. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

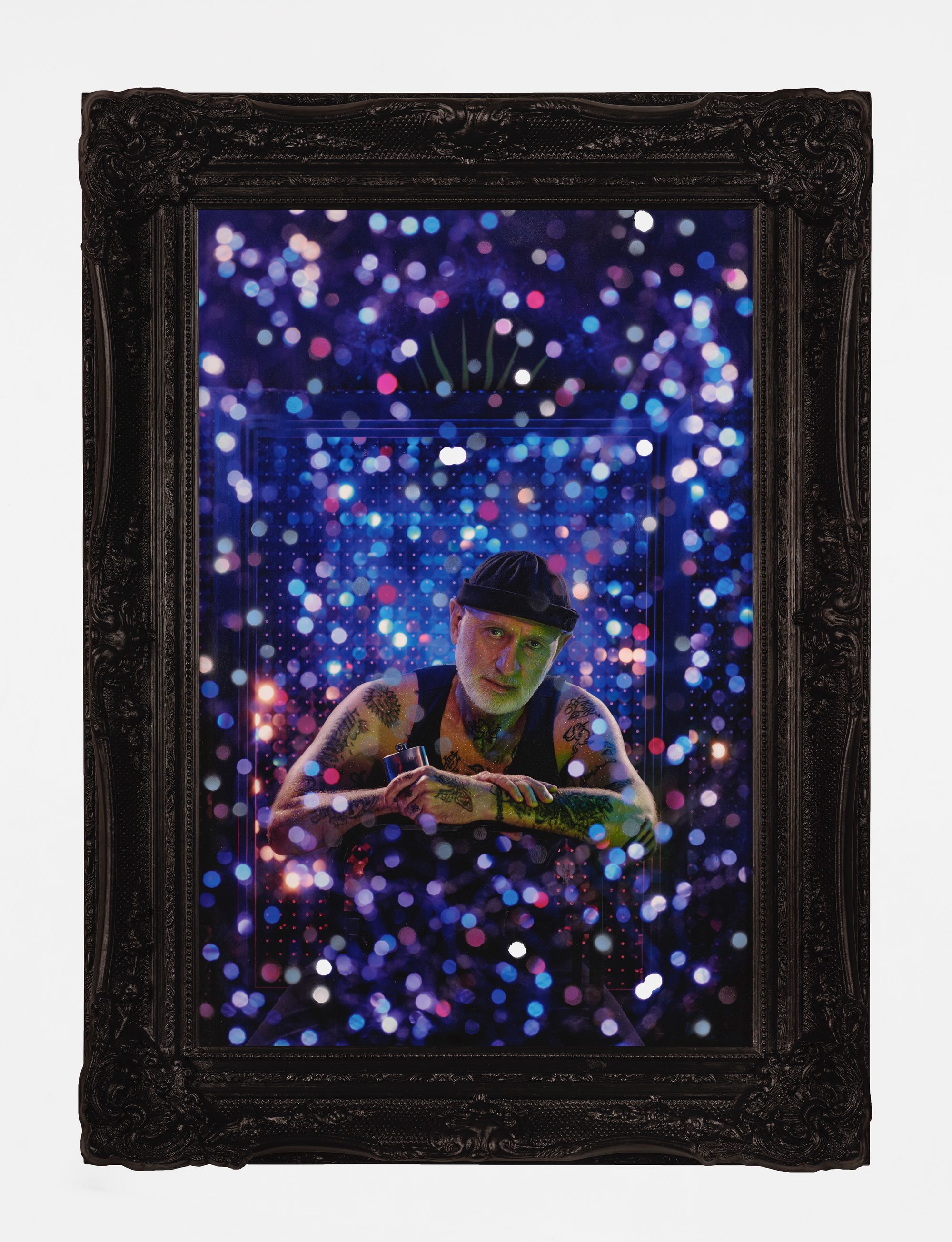

Autoportrait - Pierre, 2024. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Mary Stuart (Isabelle Huppert), 2023. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Autoportrait - Gilles, 2024. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

How is this downstairs studio and workshop space organized?

GB: We have hundreds of boxes where we sort the accessories, like different kinds of flowers. Each box is labeled with a drawing by Pierre, so we can recognize each one. There are, for example, different boxes for plastic and fabric flowers, each have their own area, and then there are subcategories of boxes with hats, wigs, stuffed animals, and fruit. When we plan a photograph, we start with the set, then the lights, then we go to the props, which means we change the sets several times. There’s a lot of improv on the shoot. Anything can happen until the last minute. It builds suspense. Then, after every shoot, everything is dismantled, and all the different elements are put back into boxes. The collection grows over time and takes over the space. Whenever I feel like we need to discard something, that’s when we have an idea to use it. Sometimes, we throw things away and regret it.

How has your work evolved over the years?

PC: We’ve had really hard times, like during the AIDS crisis — before, we were young and carefree. Time made things more somber. That’s how life unfolds. Also, the more you work, the more sophisticated you become. And the sets get larger. We refined our language. For example, we experimented with fluorescent lights in our latest show [Nuit électrique, at Templon, Paris]. The redlight district in Paris really touched us. The characters are all different genders and identities. And there’s a great choice of LED string lights, especially at Christmastime. The last time we worked with string lights was in the 80s, and we had to stop because they would heat up so much that they became fire hazards.

GB: The sets used to melt! When we had a set of snow, it would melt and almost burn, and we had to stop immediately. It’s much simpler now, with new technology.

Is your ongoing fascination with string lights related to Christmas decorations?

GB: Of course. As a child, I had a fascination with Christmas and the holiday lights in the streets. I come from Le Havre, which was destroyed and completely rebuilt after the Second World War. Christmas was a big deal. The stores were all decorated. I used to marvel at them.

PC: Lights always fascinated me. Rain on a windshield, when the wipes went back and forth, the light through that — those little moments really moved me. I grew up in a small town, too, and whenever there was a fair it was a very special moment — looking up at the stars and making the connection with the lights of the fair.

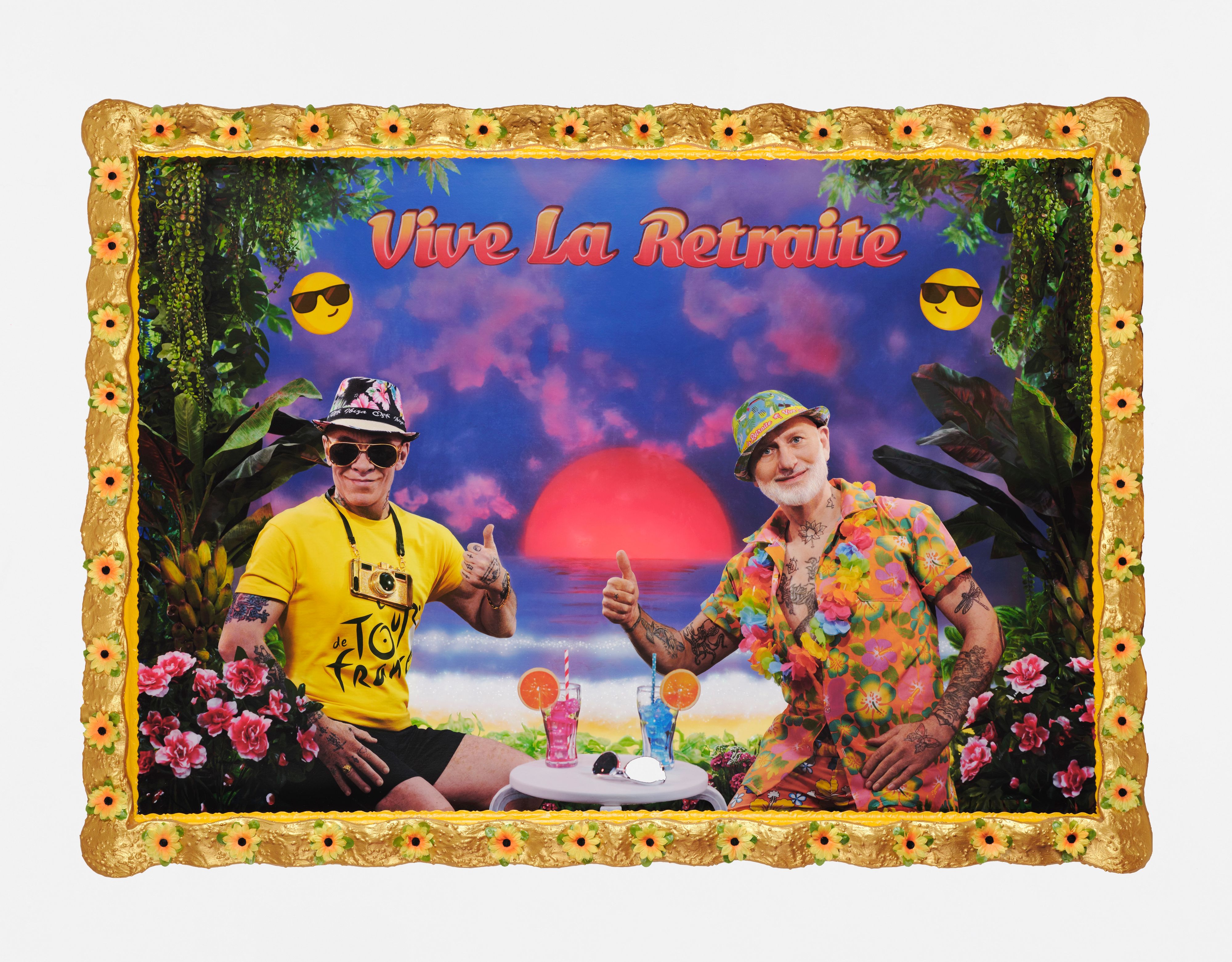

Vive la retraite (Autoportrait - Pierre et Gilles), 2024. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Do you decorate your house for Christmas?

GB: We do not need to decorate! [Laughs.]

PC: One day, Gilles invited his entire family to the house and decorated a tree and everything. He said, “Oh, did you notice my decorations?” And they said, “No, there’s nothing different.”

When you’re photographing somebody, how do you capture their charisma and also build a world in which they can exist?

GB: We cast them in a role, but the world must correspond to them. It’s a negotiation. Often, the model inspires us with a story that we project onto that person. The inspiration goes both ways.

And what happens when you’re the model?

PC: Those ideas just come on a whim, and it has to be fast. We recently decided to portray ourselves as retirees, which we thought was fun because, as old men, we know we’re never going to retire.

I mean, could you stop making work?

GB: Artists will never stop.

Do the lines between the fantasy worlds of the photographs and the reality of your relationship and home life ever blur?

GB: Everything is always mixed. Our home has always looked like a stage. People always say it's like a parallel universe when they step into our house. We’ve slept in our sets. Our work is our life. Our life is our work.

World-building is so central to your work. Have you ever considered expanding your practice into interior design, set design, or even architecture?

GB: We’ve been asked many times — by theater directors to create stages, major fashion houses to create sets, etc. But we’re not interested in that. We can’t. We need to work from home. We need to work in our own little world. We usually say we can create the poster and they can use that image to create their own sets from our world. But we’re not going to do it! [Laughs].

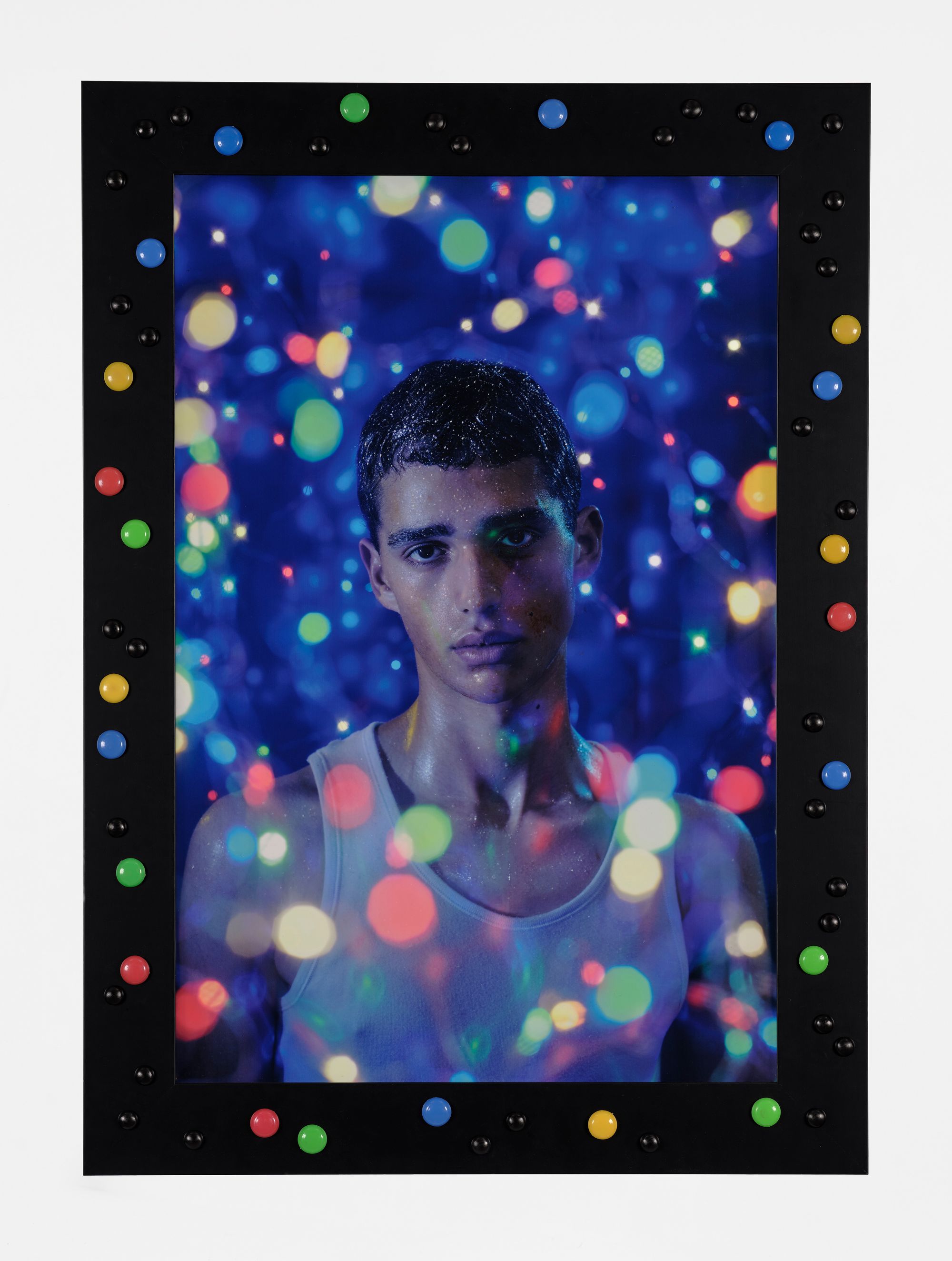

Night Club (Yannis Zegrani), 2023. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Over the Rainbow (Nassim Guizani et Lukas Ionesco), 2023. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

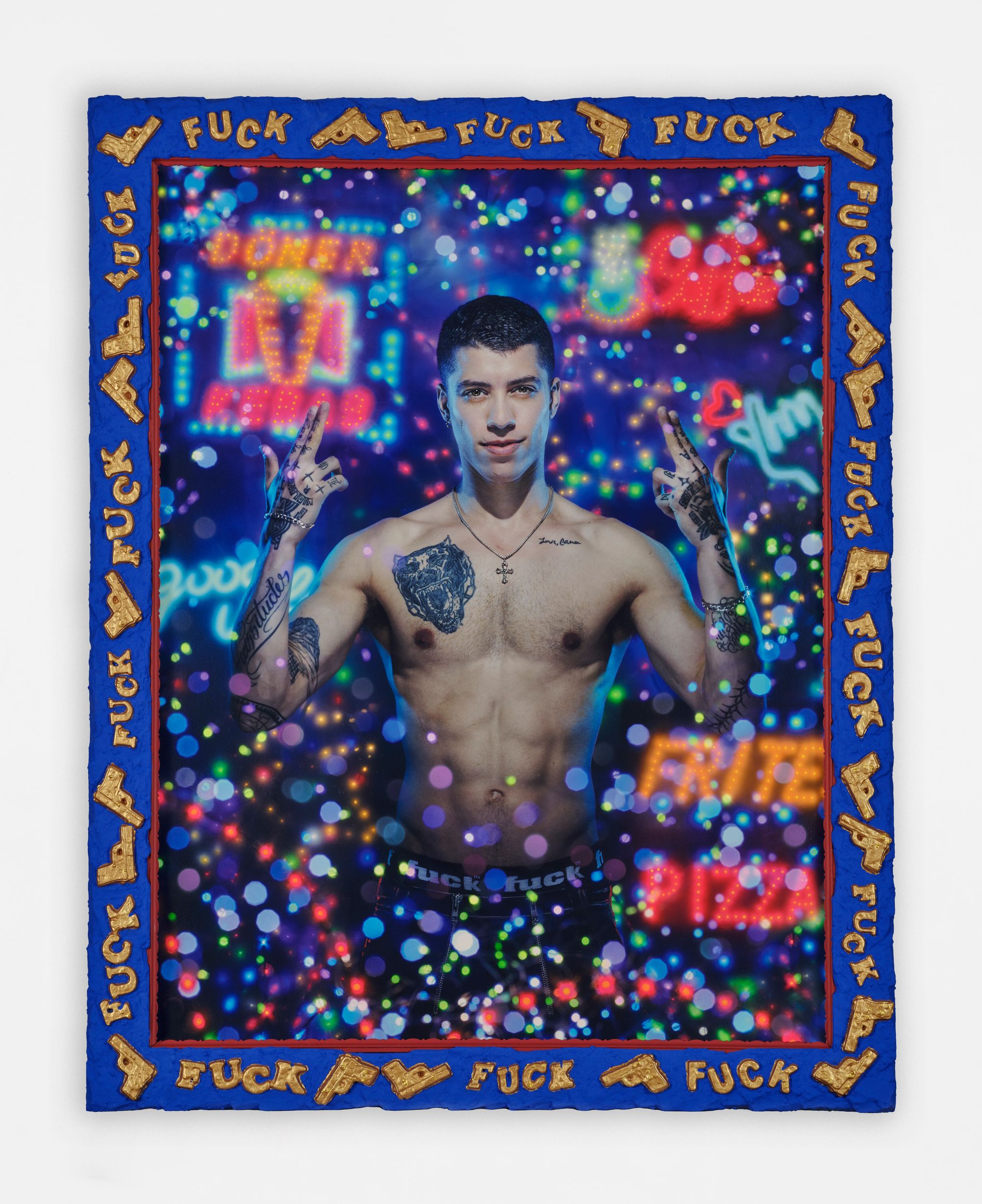

Fuck (Jonah Almost), 2023. Courtesy the artists and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.