THE GUGGENHEIM’S NAOMI BECKWITH ON THE SPIRAL OF ART HISTORY

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

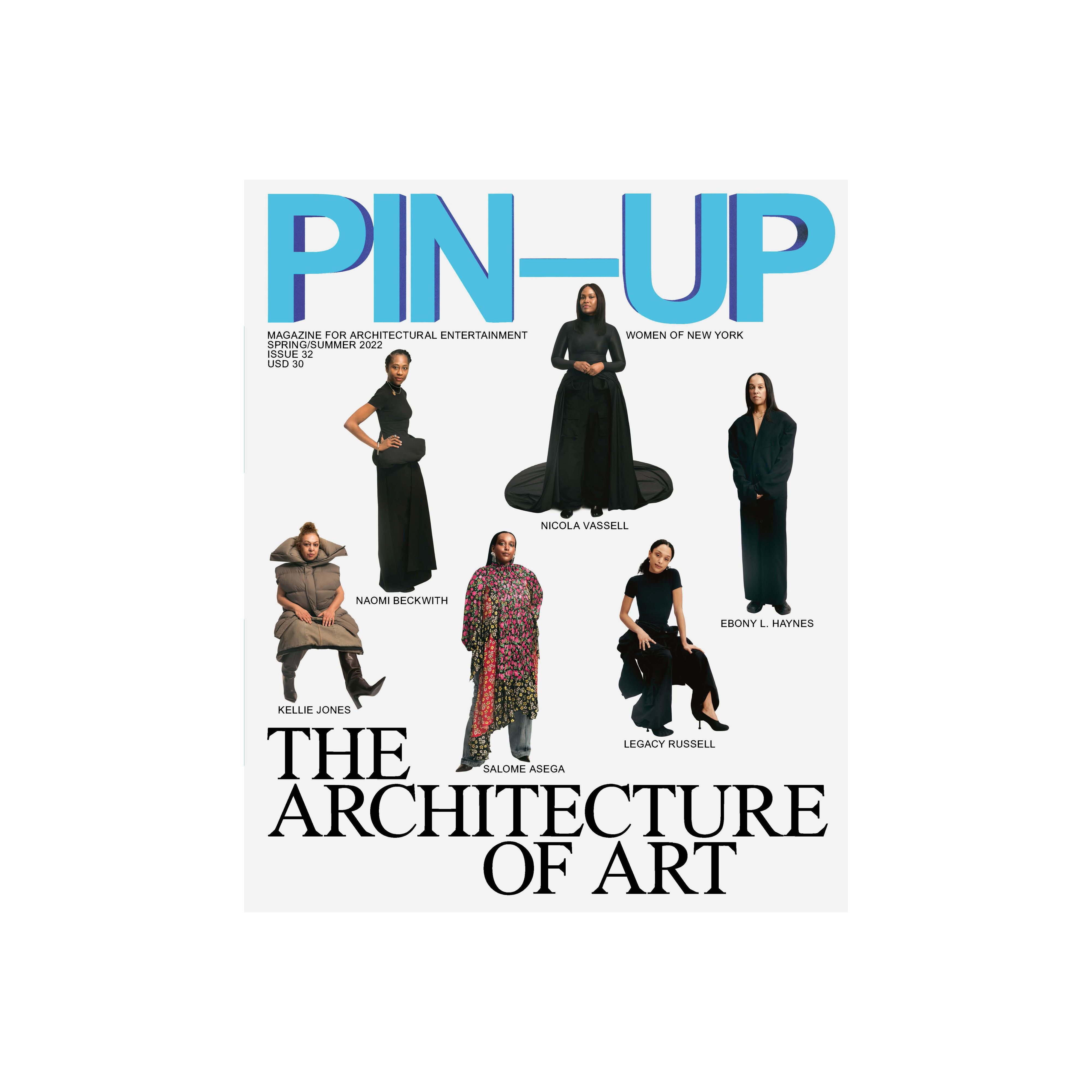

Naomi Beckwith photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

Naomi Beckwith grew up in Chicago, the city of Miesian towers and Corbusian housing projects, but as the deputy director and chief curator of New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, she now develops her curatorial practice in the spiral of Frank Lloyd Wright’s late-career organic icon. Before being appointed to the Guggenheim, in 2021, Beckwith passed through the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia and the Studio Museum in Harlem, after which she became the Manilow Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA). Beckwith’s approach spotlights lesser-known histories and glossed-over narratives: at the Studio Museum, in 2010, she showed Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits of Black figures pulled from magazines and scrapbooks, while in 2018, at the MCA, she co-curated the first major survey of multidisciplinary artist Howardena Pindell. She says her approach to curating is like a spiral, moving forward and constantly turning back on itself. Beckwith is keenly aware that change is not possible unless you look to the past in order to stake out a more equitable future.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: I really loved the story you shared earlier today about what your former boss told you regarding fashion and curatorial practice.

Naomi Beckwith: [Laughs.] I did have a boss early on in my career who said one can’t be a curator without a Comme des Garçons jacket. It’s really saying two things: there’s the shallow reading of it, which is that in many ways it’s about looking the part; but it’s also a statement that says one’s commitment to curating is as much about understanding and sensitizing oneself to aesthetics broadly speaking as it is about the visual arts. It’s also about fashion, design, and pop culture. These are all of the things that sharpen one’s eye in terms of how one imagines pulling together influences into the framework of curating. I couldn’t just own the jacket — I had to study and understand its technical innovation.

What is your relationship to architecture?

I’m a child of Chicago and was educated in certain idioms of Modernist architecture. At public school, growing up, we had to take Illinois and Chicago history, courses that looked at the architecture of the state and city, which is incredibly proud of its relationship to Frank Lloyd Wright, to the Bauhaus, and to skyscraper language. My relationship with architecture started very literally with this narrative of Chicago as a city of Modernist activity, but there’s also a metaphoric relationship, given that it’s the site of one of the world’s largest public-housing projects, done in the great Corbusian International Style, which would end up being demolished and taking a community along with it. You can’t be a citizen of Chicago without understanding the relationship between edifice and community, between form and function. My education in architecture has been about form and the uses it ends up performing. What is the performance of form? Who utilizes those forms and who has access to them?

The Guggenheim Museum as a concept and as an arts institution has long branded itself through architectural spectacle, first with Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1959 building in New York, then, four decades later, with Frank Gehry’s 1997 Bilbao Guggenheim, after which people talked about the Bilbao effect.

When Solomon R. Guggenheim and Hilla von Rebay, the museum’s first director, were looking for an architect, they sought someone who could give them a form that would embody their ideas of what art can do and should be. They did not want the redundancy of the International Style — they were looking for someone who had a sense of spirituality, metaphysics, and earthiness. Hilla von Rebay, specifically, lobbied for Frank Lloyd Wright to design the museum, and it’s a New York City marvel.

That reminds me of Phyllis Lambert’s influence over the design of the Seagram Building, and how it shifted the standards of functional Modern architecture.

Yes, a lot of Modernist architecture wouldn’t exist without women. As the Guggenheim started to create a constellation of sibling institutions around the world, we needed to make sure that the building and the architecture matched the original ambitions, and that we were not creating white cubes over and over again. We wanted to create edifices that in and of themselves were a kind of monumentally scaled futuristic sculpture. Hence Frank Gehry in Bilbao, which you rightly say stimulated a kind of economic regeneration in the Basque Country. Now Frank is working on the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, a country deeply invested in creating iconic buildings. I think Frank rose to the challenge of creating a form that we hadn’t seen before in his vision for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

What is it about the Frank Lloyd Wright building that speaks to you?

As many people well know, Spiral was an important African-American art collective in downtown New York in the 1960s. These were artists trying to understand what their relationship was to the greater art world, especially under strict social segregation. As a group, they have always stood as a real signpost for me around artistic responsibility. Then there’s this notion of sankofa that’s incredibly important to me. It’s a word from the Twi language of Ghana that loosely translates as “Go back and get what you need to claim.” I used to say that it’s about looking back and forward at the same time. It’s saying that one needs to study history to understand the foundation of the work in order to build on what’s already been done to move it forward. The spiral shape of the rotunda in the Lloyd Wright building is to me a reiteration of sankofa.

That makes me think of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective, established in London in 1983, and of the Ethiopian-produced film Sankofa, which came out in 1993.

Yes, it’s something I deeply believe in that has always been present in my work. It’s the Spiral group, the work I did with Horwardena Pindell, and the essay I wrote on her work that speaks to having a practice that moves forward and constantly turns back on itself. The spiral is a motif that continually shows up in Pindell’s work. I love many ideas that come from Black history, Black studies, and Black art that intersect with the Modernist idioms of Frank Lloyd Wright. These things aren’t separated across continents, but they are convictions and ideas that intersect through the ideas of many people. Everyone who visits the Guggenheim acts this out when they look across the atrium. It’s organized in a way that you can see the layers of all the ramps on the spiral. You’re looking at the beginning of the show, the end, and all the people moving through it in one glance, and you can take in all of those layers of history at the same time.

For me there’s something similar in Pindell’s work, which seems to focus on the idea of mapping oneself onto a place. It reads as citational. It’s very anthropological.

Yes, mapping is a great word. It makes me think of Adrian Piper and Carrie Mae Weems in contradistinction. I think they came to very similar conclusions very early on from two different directions. We often think of the art world and artmaking as a tabula rasa, the empty studio, gallery, museum, and we come in and act as artists and curators and build something from nothing. One of the things that Piper and Weems were very clear about was that there was always something that precedes the space that we think of as empty. There’s already a plentitude of histories, cultures, and exclusions that we should be wary of inside that space. Piper’s most controversial works were the performances she started doing around the art.

Yes, especially the Catalysis series.

Exactly. She began to think of herself as an active agent who challenges the idea of neutrality.

The myth of neutrality?

Yes, the neutrality of the art world. That we were these rational figures who came in and acted on the tabula rasa. She really believed that we were marked by our history, intellectual abilities, and, as she eventually pointed out, by our race as well.

She understood the politics of space.

The spatial politics were invisible until she walked in as a different kind of being. Then, suddenly, the walls, limits, and parameters became very clear, but only once she disrupted them.

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.