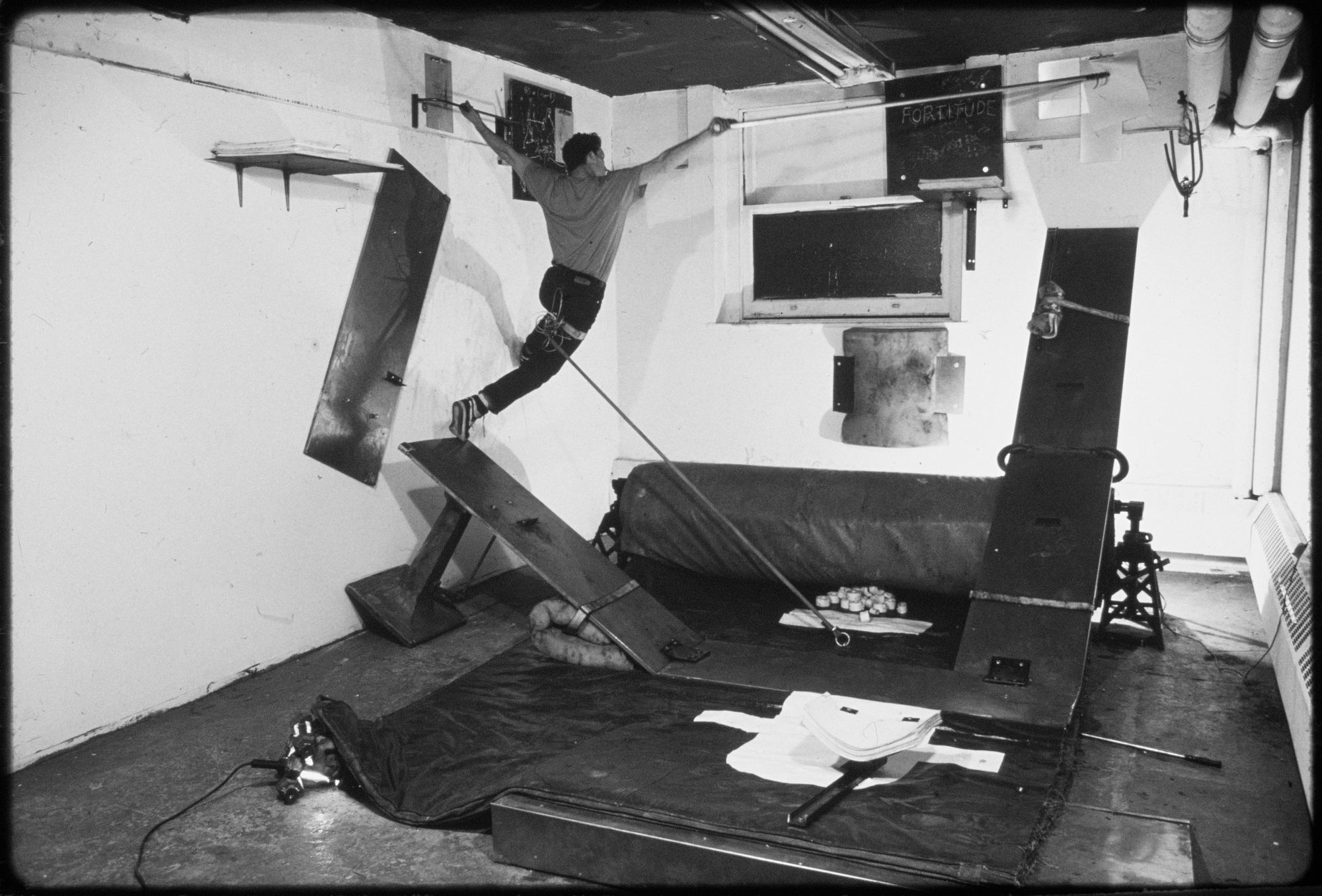

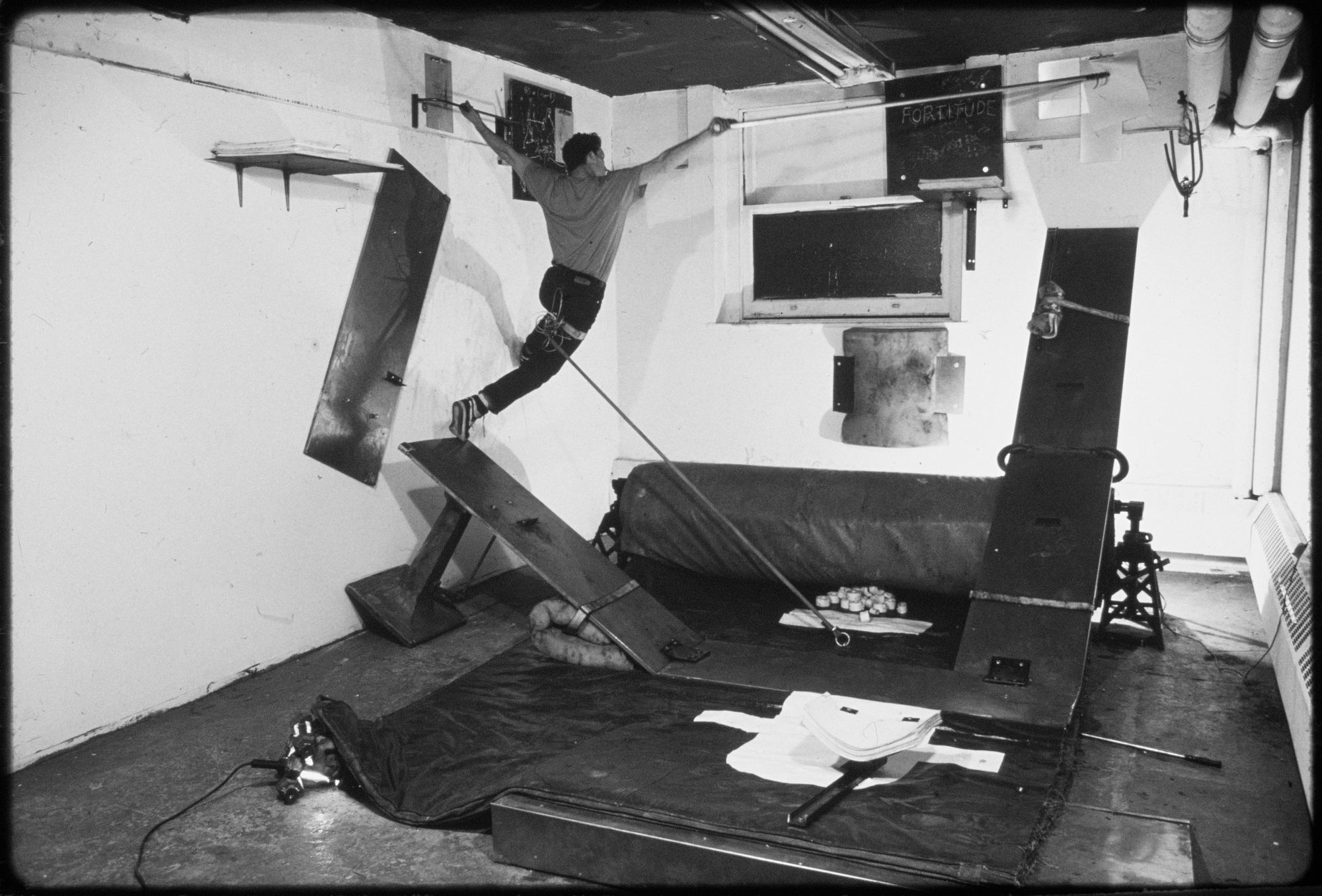

Matthew Barney, Drawing Restraint 2, 1988; Black-and- white video with no sound; 05:01 min. © Matthew Barney. Photograph by Michael Rees.

Matthew Barney photographed by Ari Marcopoulos for PIN–UP.

Artist Matthew Barney describes his ongoing series Drawing Restraint, which he began as studio experiments in 1987, as “an endless loop between desire and discipline.” In the piece, which brings together performance, film, and sculpture, he created serpentine obstacles for himself — impeded by obstacles, harnesses, and ramps, he struggled to put a pencil to paper. It’s an embodied performance that draws on Barney’s youth spent competing as an athlete, rooted in a fundamental truth of sports training: (muscle) growth only comes from subjecting yourself to forces of restraint. In a similar manner, the body is a recurring element in Barney’s elaborate aesthetic systems. In another early work, Blind Perineum (1991), he scaled the walls of New York’s Gladstone Gallery using ice picks, dressed in a blue swimming cap and almost nothing else, before inserting a screw into his rectum. In the film River of Fundament (2014), he represented the body of Norman Mailer as three different American cars, one of which is a 1967 Chrysler Crown Imperial, which also appears in Barney’s career-defining epic The Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002, named for the muscle that raises and lowers the human testes). Blood, feces, hormones produced by the placenta during pregnancy, self-lubricating plastics, and petroleum jelly make up the raw micro-material of his works, which often play out at massive scales — think football stadiums, opera houses, the Chrysler Building. Barney has generally leveraged the mundanely corporeal and the mythically grandiose in equal measure. In this conversation, he delves into these two modes of his practice, while discussing his forthcoming project, Secondary, which will revisit his athletic roots, his mapping of geological time, and his early-career anxieties.

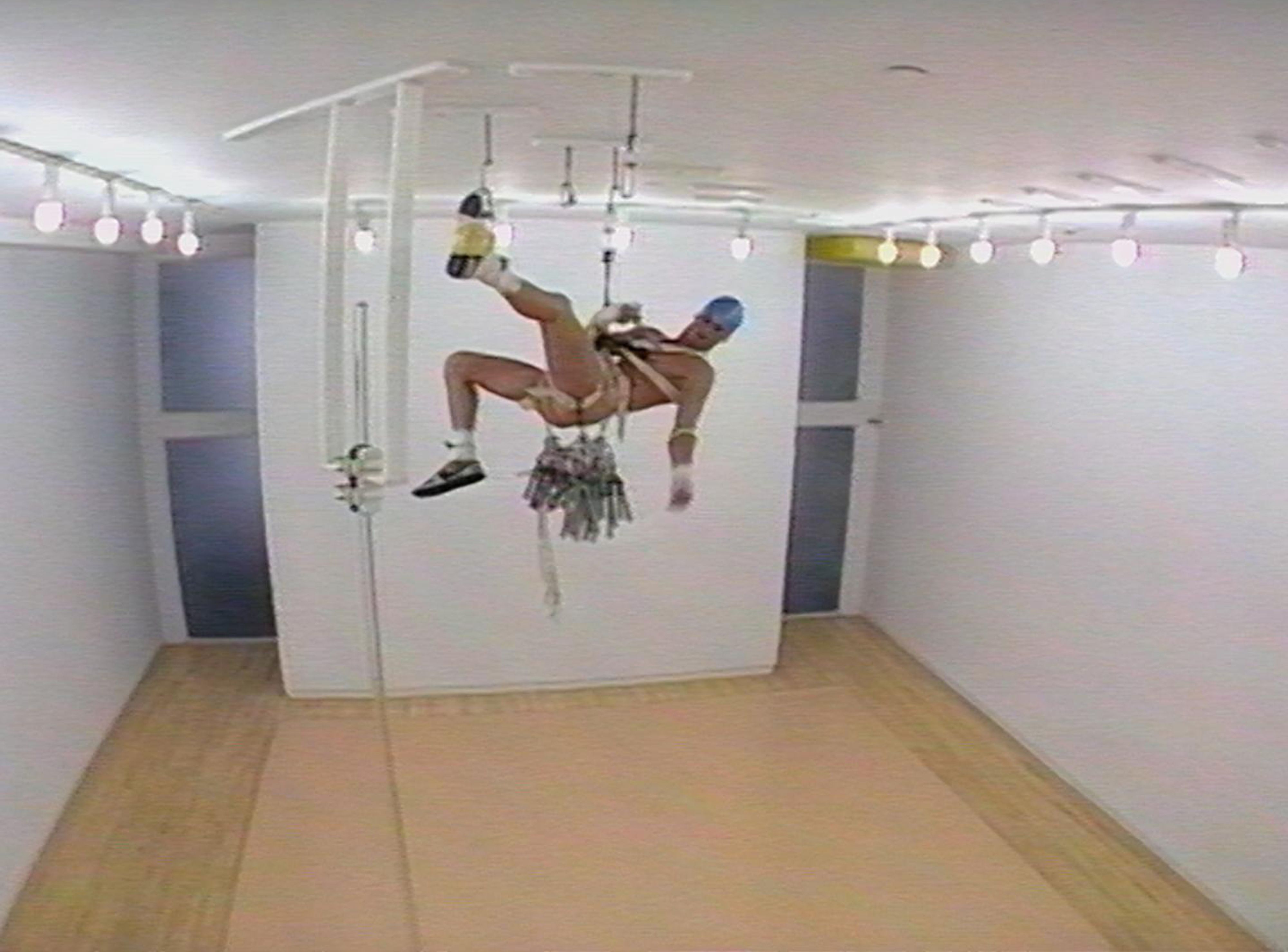

Matthew Barney, Blind Perineum, 1991; color video, silent, [video still]; 1:29:30 hour. © Matthew Barney

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What is your relationship to architecture?

Matthew Barney: When I’m working on a larger project it usually begins with a place. It’s easier for me to think of architecture as a character within the narrative. I think my primal scene would be the stadium, which I have revisited a lot recently because of my forthcoming project, Secondary. It deals with the same set of dynamics that were at play in my work 30 years ago, specifically the Jim Otto and Harry Houdini works [Drawing Restraint] from the early 90s, where the gallery served as an athletic arena of sorts. In Secondary, my studio is serving a double role, both as a stadium and a place where sculpture is made. I often want architecture to function like the larger body within any work — a kind of body that can occupy different scales simultaneously. Stadium and opera-house architecture speak to me because of their corporeal qualities. Being in an opera house feels like being inside someone’s chest, in the sense that it’s a resonator.

Do you treat your studio practice like a soundstage?

Sometimes it’s archeological. When I was location scouting in Detroit for the Khu performance in River of Fundament, you could really feel the different layers of history in the city, from the prehistoric salt mine and the mineral deposits that brought the auto industry there to the opulent architecture of industrial wealth and the ruins and relics of it that still remain. You can see all of those histories converging at once. And I get so excited by that. I think the way the piece functioned archaeologically excited me a lot.

Matthew Barney, Drawing Restraint 2, 1988; Black-and- white video with no sound; 05:01 min. © Matthew Barney. Photograph by Michael Rees.

Matthew Barney, Secondary, 2023; Five channel video installation with sound, [production still]; 1:00:00 hour. © Matthew Barney. Photograph by Julieta Cervantes.

I liked reading about how you always return to the drawing no matter if you’ve finished the piece or not.

Drawing is an important tool for me — it’s part of the method of mapping the system. I’m a system maker more than anything else, and I tend to work out the system through drawing. I would say that the sculpture ends up being a distillation of the various forms within the narrative that also belong to that mapping.

The typology of film work and that of physical objects is so different. It feels like they’re coming from opposing entities concerned with particular material histories. What are you trying to confront in the tangible object?

It’s often inciting a reaction that resonates with me through these conflicting oppositional forces. This plays out through juxtaposing images in films, but it’s more elusive in sculpture, which is ultimately more engaging for me. I’m interested when a material that has certain histories and chemical properties is placed in proximity to another material with opposing properties and histories. It’s all about alchemy, and what kind of energy is created when that proximity is modulated.

Let’s talk about the inaugural performance of Drawing Restraint at Regen Projects in Los Angeles and Gladstone Gallery in New York, where you scaled the walls of the space nude. In a sense it felt like you were activating the architecture of the space.

Yes, maybe on a more microscopic level. It was largely about those characters embodying the physicalities of Jim Otto and Harry Houdini while moving through the body of the gallery like competing cells within the body’s system. Those two shows both involved climbing across the ceiling — they mirrored one another. The one in Los Angeles happened first, then the one in New York six months later. Jim Otto was a center for the Oakland Raiders in the 70s — he wore the white “away” jersey in the exhibition in L.A. and the black “home” jersey in New York, while Houdini the escape artist wore white poolside drag in L.A. and a black evening gown in New York.

What was the inclination to climb it while hoisted? You weren’t hostage to the situation, you had autonomy but were tethered.

I don’t know for certain. I was so young first of all. [Laughs.] My relationship to the art world was new and I had just started exhibiting. It wasn’t about escaping from that power structure, even if the work focused on the character of an escape artist. It had more to do with creating a form whose parts could continually change. I was really interested in the kind of transformation that could happen within the characters I was creating, because the general thinking was incredibly binarized. They were two characters in opposition, yet both kept changing. I was also thinking about it at the time as a kind of archetypical chase scene of sorts. I was watching a lot of horror films and was really interested in the viral quality where entities would leap from one host body to the next. I was thinking about the characters in my work in that way, and how they occupied architecture as guest bodies within a host body — moving through the host and pushing each other apart.

Matthew Barney photographed by Ari Marcopoulos for PIN–UP.

Matthew Barney photographed by Ari Marcopoulos for PIN–UP.

When did you start practicing art?

I was making art at Yale as an undergraduate. I met a number of artists who were in graduate school at the time. They were like my mentors, or my older siblings. We ended up starting out in New York together. My entry point into art was through my relationships to those artists.

What is your relationship to time?

I’m interested in setting up a work that has multiple relationships to time. It’s one of the reasons I use architecture — for its relationship to the geological condition — and why I continue to make sculpture and moving image work. They have different relationships to time, but I consider them both time-based in the sense that the kind of sculpture I make has more to do with material behavior than purely with form.

Matthew Barney, DRILL TEAM: screw BOLUS, 1991; cast petroleum wax and petroleum jelly, Olympic barbell and dumbbells, cast, Cramergesic dumbbell, titanium ice screws, carabiners, prosthetic plastic locker, NFL jerseys, dimensions variable. © Matthew Barney. Photography by David Regen.

Matthew Barney, OTTOdrone, 1992; color video, silent, [video still]; 18:46 min. © Matthew Barney.

Do you still think of your film work as a form of sculpture?

Some of the films take on the guise of a movie. It always feels like I’m dressing it up as something else but it’s fundamentally a film in that way. All my needs come from sculpture making though. What got me using a camera in the first place was really to do with the interaction between objects and space, and activating that space through performance. It’s not about constructing narratives and being interested in light — that’s not particularly my thing.

You alter animal and human bodies. How do you conceptualize and develop these characters?

There’s definitely a range — most of the characters start with a drawing, followed by a discussion with a prosthetics artist. I was thinking a lot about horror films and the transformation that could happen in that space. I was interested in adopting the techniques used in horror films in the 70s and 80s, when they were still working with rubber, before digital effects came along. With prosthetics, you pretty quickly realize the limitations of the performer’s body, and even more so with animals — like the zombie racehorses in Cremaster 3. [Special-effects artist] Gabe Bartalos designed spandex suits that the horses would be comfortable in while running, and then he applied latex-foam anatomical pieces with blood and gore onto the suits. It really was a tour de force.

How did you negotiate putting your life into your work? Because there’s Matthew Barney as artist, as performer, as model, and as athlete.

The athletic thing was more fundamental in the sense that I had been doing that my whole life at that point. I knew how my body could function within the athletic context. As I started making art, I was naturally attracted to endurance-based performance work that used the body and time. Working in the fashion business was more of a job, but I certainly learned a lot about how malleable my image could be — that was useful.

Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 1, 1995, 35 mm film (color digital video transferred to film with Dolby SR sound), [production still], running time: 40:30 min. © Matthew Barney, Photograph by Michael James O’Brien

You came into being as an artist when there were very distinct divisions between hyper-masculinity and femininity. Was there any tension between you as an athlete and you as an artist?

I remember this particular moment during a studio visit with Michael Reese, one of the graduate students at Yale. It was a really influential conversation for me because he was looking at the work and speaking rather critically about it, and he turned to me and said, “You’re a jock and you’re from Idaho. You have something very specific in your past and your experience and you should figure out a way to work with it.” I found it very liberating, actually, because at the time those two things felt so polarizing and monolithic. Although I could look to somebody like Bruce Nauman or Carolee Schneemann and see that they were pushing the limits of their bodies, I didn’t relate to them at the time. I didn’t understand how I would do that, but I gave myself the permission to use my athleticism as an entry point — as away to use my body as a tool. That was helpful.

So Bruce Nauman and Carolee Schneemann. Who else?

I was studying Joseph Beuys’s work in those years — as much of it as I could find. It wasn’t just to do with the fact that the Internet didn’t exist and there were only a few books available on him at the school library — it was the way he withheld so much. A performance of his might be represented by one photograph. Maybe there was a film, but it wasn’t easy to get your hands on back then. I only had access to the picture and I would have to imagine how the performance might have operated. And I loved that. I had to learn to understand how the narrative worked from the relationship between the object and a few photographs. I appreciated the space for interpretation around that work. And then there was Houdini, who was an important bridge for me between an athletic, bod-based practice and an approach that was grappling with invisible and mythological forces. And very American.

What’s your relationship to mortality? As an athlete, you’re hyper-aware of potentially having a short career due to injuries. How did that thinking manifest in your artistic work, where your body is also implicated.

Cremaster 1 was the first time I wasn’t playing a role on screen. That decision felt really liberating because I had to prove to myself that I could remove myself and be absent in that way.

But you were still there.

Yes. I’ve done a fair amount of work since then where I’m not a central character. With the Drawing Restraint series, I think it has become more and more about my aging body and the dynamics of performing these actions as an older body. Secondary is cast with dancers who are all my age, with some older people, and I play a secondary role. The central narrative has to do with an accident that happened on a professional football field, so I wanted it to function more abstractly through the lens of memory. I excavated a trench in the floor of my studio on the East River, exposing a broken sewer line. The core narrative describes the lead up to the athletic event, which takes place on the football field in the center of the space, and the tidal pool in the trench acts like a clock for the event. Then there will be work stations, featuring four or five sculptures from past projects through my whole working life that are being restored. I wanted to bring my own histories to bear on this new project, blurring the differences between the past and the event taking place on the field to find a new form.

Matthew Barney, Drawing Restraint 17, 2010; Two-channel color video with no sound, [production still]; 31:52 min. © Matthew Barney. Photography by Hugo Glendinning.

Matthew Barney, Secondary, 2023, five channel video installation with sound, [production still], running time: 1:00:00 hour. © Matthew Barney, Photograph by Julieta Cervantes.

How has the development of technology influenced your practice?

When I look at the Cremaster films now, the difference is remarkable in terms of video resolution and sound. During those years, video changed so much from piece to piece, but so too did my ability as a moving-image maker. I got my filmmaking education during that time.

Do you condition or rehearse for the roles you play?

I usually do, but even more so for Secondary. I play the role of Ken Stabler, who was a quarterback for the Oakland Raiders — one of the first-known quarterbacks to be diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. I trained with the movement director David Thompson to learn how to safely fall. I wanted to work out a movement vocabulary where Stabler’s body would be hit by an invisible force, and he’d be thrown to the ground with no one else present.

It’s hard to fall.

[Laughs.] It is, especially without getting injured. When I know I’m going into a shoot that’s 30 or 40 days, atrophy starts to kick in and you really start losing it by the end. It’s something that I need to train and be ready for, especially these days.

Can you speak to the fragmented vignettes and choreography in the film work?

Using movement as a sort of vocabulary in the work was pretty intuitive for me. I wasn’t really thinking about formal choreography until I worked with that dance group in Cremaster 1 on the football field. But the movement in that piece was so much about mass ornament, cellular movement, and self-organizing systems. It didn’t have much to do with capturing an emotional arc or even a specific energy within one character. I think I tend to try to avoid that more generally. I guess you could say I definitely came to choreography through the back door, and it does feel like a new territory. Secondary has been an opportunity to go deeper into the vernacular of dance. And working with David lets me work through these other dancers and their specific vocabularies which are new to me. It’s a different kind of collaborative space for me, and a fertile one.

Do you feel like you have to work harder now?

When you’re 24 years old you’re working intuitively. It’s different. From a performance standpoint, it’s about self-consciousness and continuing to find ways of working that are not overly self-aware. That’s my relationship to complexity — to push myself into a space that has a different kind of complexity, one that I don’t totally understand. This thinking is the reason why the work changes from project to project and why these different settings become so dominant, because they’re often places that I don’t know.

Perhaps your most famous work is the enigmatic Cremaster Cycle. What was it about?

It was about the mapping of an organism or form that’s undergoing a developmental change. Structurally it was about mapping that organism over five geographical spaces between Europe and the United States.

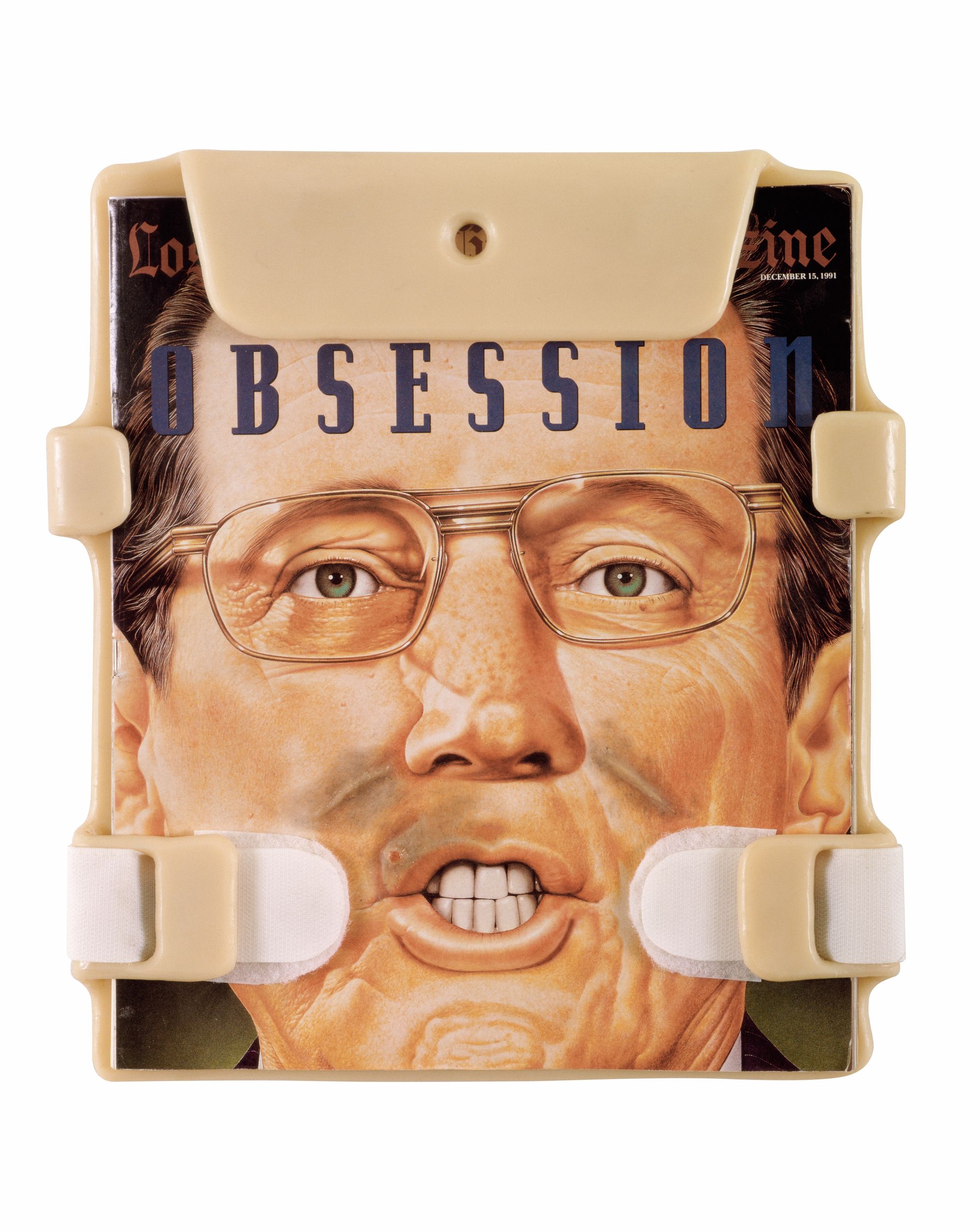

Matthew Barney, LIGATOR general managing partner, 1992, vaseline, silicone, rubber and wax on newsprint with velcro and prosthetic plastic clipboard, 12-1/2 x 11-1/2 x 3/4 in. © Matthew Barney

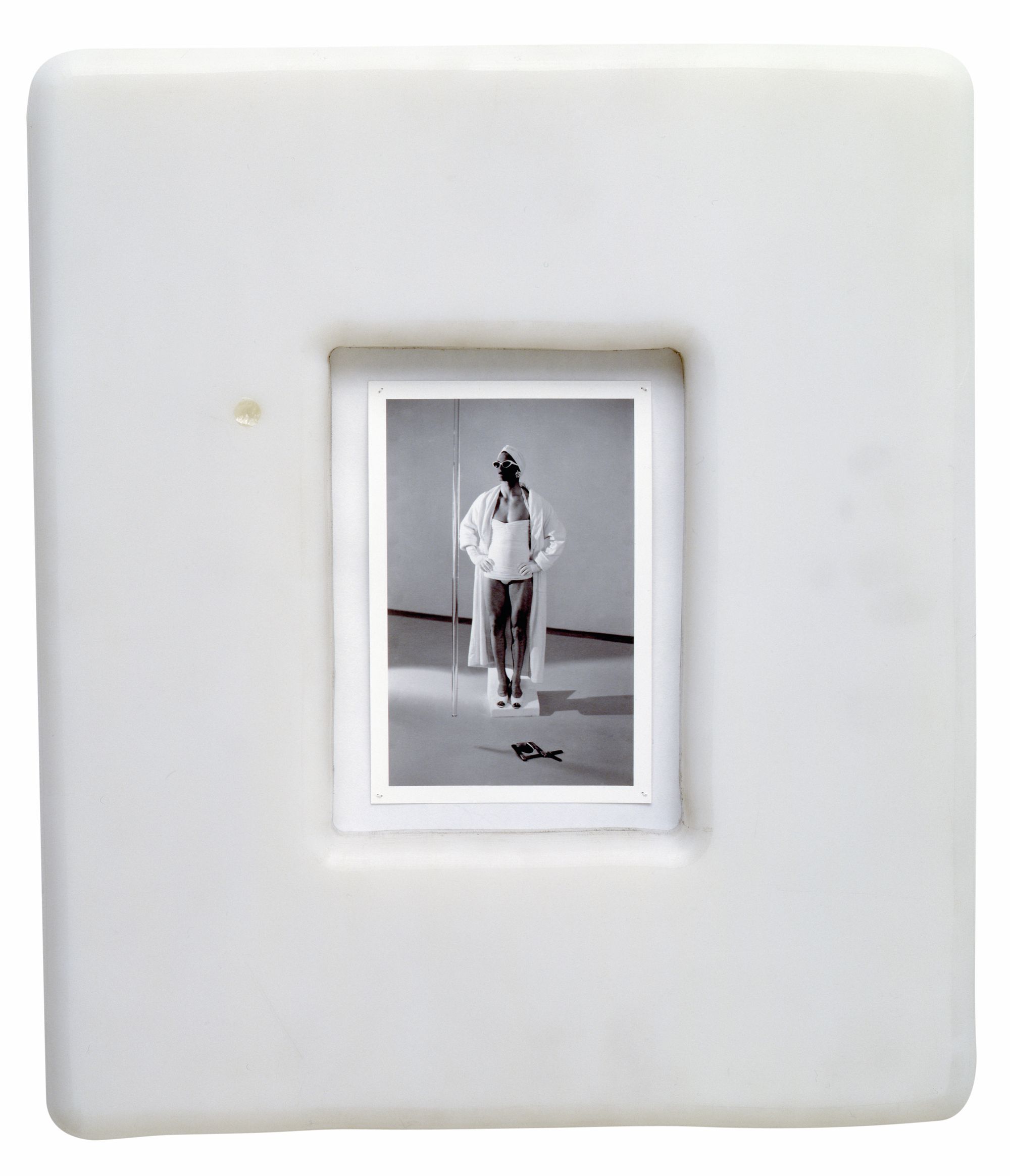

Matthew Barney, Delay of Game (manual A), 1991; Gelatin silver print and petroleum jelly in internally lubricated plastic frame, 15 x 13 x 1 in. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

Matthew Barney, Cremaster 4, 1994 – 95; 35 mm film (color video transferred to film with Dolby SR sound), [production still]; 42:16 min. © Matthew Barney. Photography by Michael James O’Brien.

Are you the organism?

Yes, in a certain way. It had an autobiographical layer in its structure. But in another way it was about mapping a system that’s just learning to express difference. In that sense I was trying to model a visualization of the creative process. I think of the body as a kind of metaphor, and I was thinking about how the sex of the developing fetus can be in an undifferentiated state for quite a long time and how exciting that is, both as a biological curiosity but also as a model for the ways ideas take form — and how they remain undifferentiated until they calcify as they become more determined. And then you have to say what it is, you know? I think in a way the piece was about prolonging that sort of gestation period and thinking about that kind of model for creativity in general. It was about leaving something open and not determining what it is until it’s able to stand on its own. It meant many things to me at the time.

What does it mean to you now?

My process is probably a lot more organic than most people think it is, because the work is these larger complex pieces that require a lot of people, resources, and foresight in a certain way. But the process is very organic. I’m becoming more interested in creating structures where decisions can be made through an improvised process. At the moment, I’m really interested in the working methods of dancers and choreographers, and their work-shop format, where one creates an environment and constraints and people are able to respond and improvise their way through that structure. Visual art tends to be less collaborative. I’ve never had an isolated studio practice, so working alone isn’t natural for me. I love working with people.

Matthew Barney photographed by Ari Marcopoulos for PIN–UP.