Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1996–2004) in Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa. Photo courtesy the artist.

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1996–2004) in Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa. Photo courtesy the artist.

Since the late 60s, Mary Miss’s work has pushed postminimalism out of the studio and into the open through her large-scale, enigmatic structures that straddle sculpture, landscape, and architecture. One of her major permanent commissions, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1989–1996), is a network of paths, canopies, and mounds arcing around a wetland adjacent to the Des Moines Art Center. One walkway floats above the pond before plunging beneath its surface, creating a recessed chamber where one can sit below the water. Referencing the site’s past while offering visitors new ways to explore the restored wetland, Miss’s constellation of passages choreographs people’s movement through the environment, punctuated by intimate moments of thoughtful presence. Miss is one of the preeminent women pioneers of land art — she was recently featured in the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas’ exhibit Groundswell: Women of Land Art — and Greenwood Pond: Double Site is the only installation of hers in a museum collection. Last October, the Des Moines Art Center abruptly closed the piece for structural review, notifying Miss in December that the piece would be demolished. Public outcry has forced the museum to release a statement, cynically promising to “honor the legacy” of the artwork while dismantling it with “strong resolve.” Below, Miss discusses her vision for the project, how it brought her from land art to environmental work, and her thoughts on the demolition plans from her Tribeca studio.

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1996–2004) in Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa. Photo courtesy the artist.

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1996–2004) in Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa. Photo courtesy the artist.

Oscar Peña: Did you choose this exact location for the piece?

Mary Miss: Julia Turrell [then the director of the Des Moines Art Center] asked if I would come to Iowa and see about doing a project on the grounds of the museum, which is in a city park. I got down to this site and there was a little crummy building that was called a warming house, and there was green stuff growing all over the pond because all the runoff from the nearby roadway was flowing in and polluting it. It was in very bad shape. It had become derelict, a kind of problem area, and people weren’t using it anymore. This was probably in the late 70s, early 80s. Julia had this idea that’s become important to me: cultural institutions should get outside their walls and impact the communities they’re in.

Who did you collaborate with on this project?

At the time I was getting fed up with collaborating with architects who were always like, “Your ideas are good, but get rid of you.” So I started the process of becoming more familiar with the site and its history, learning about how important it had been to people as a skating area back when there were colder winters. I learned about the history of Iowa, and I knew someone there who had good connections with the Native American community, so I met some people through him. I found a botanist at Iowa State who took me out and talked to me about wetlands — what lived there, how they functioned, and the fact that 90% of them in Iowa had been drained and tiled for agriculture. There was a local garden club that I started interacting with because I got this idea that a demonstration wetland could be something interesting to show people in a city, to make them more aware of the landscape that they don’t see as they drive along the highway. I thought that was kind of funny because people make fun of garden clubs, and I liked the idea that these women were really into it. I was just trying to engage people with this place and give them the experience of it.

I don’t feel like your earlier projects had such an explicitly ecological angle.

No, they didn’t. My previous works were really about that interest I had about the collision between the built and natural environment, but not so much about ecology. I was really interested in the language of architecture because of the engagement of the individual. From the get-go, my work has always been about how to engage people and make them pay attention without just making the biggest, heaviest, most expensive thing possible. How can engagement happen with people who don’t know anything about art? There’s got to be something visceral or psychological that makes the work possible. This was the first project where it was much more specifically about the environment. The idea of being able to reveal the whole process that a wetland represents was very interesting to me — looking out at the water and traversing this narrow walkway through the grasses to a lookout where you can watch the birds. There’s a bridge where you can sit, but for me, the heart of the project was the recessed walkway. I thought that would be such a wonderful thing: to be able to get down and be eye-level with the water without actually being in the water.

Mary Miss, South Cove (1984–1987) in Battery Park, New York, New York. Photo courtesy the artist.

Was that recessed walkway a big engineering challenge?

No, but it ended up being a challenge to maintain it. If this project ever gets resuscitated, I would want to deal with this. There’s runoff coming down from a very busy street above the park and there needs to be more filtration of what’s coming off the roadway. This outfall kept getting clogged, which would flood the walkway. There was a pump, but it would burn out because it was having to work all the time. That problem really needs to be addressed, because without the underwater seating, it’s more like a nice park, you know? One experience like that can really transform the place and not have it just be landscape design.

Most of your big installations before this were temporary. How did you approach this one differently?

I knew they were temporary, so we spent really modest amounts of money on them. I think to do the underground project (Perimeters/Pavilions/Decoys, 1977–78), I had $10,000 to build on approximately a seven-acre site. I was so happy to get to see something materialize, especially in those early years. I built it by myself and dug the hole with a big piece of equipment, although I did have a local kid helping me. I was teaching at Sarah Lawrence College two days a week, but I was out [in Roslyn] five days a week for a year building it. When I did the tower elements, I got two guys who knew how to do carpentry to help me just because I couldn’t get those big posts up. But when a museum offers you an opportunity to do something, it’s not only that you get to see it materialize, but that it gets to stay there. It was such a big deal for me. And it’s the only museum installation that I’ve ever done. There was no question in my mind that Greenwood Pond: Double Site could be easily maintained. If I can build it, don’t tell me it isn’t maintainable.

Especially when you see all the money going to James Turrell’s Roden Crater (1977–present) or Michael Heizer’s City (1970–2022).

You hear of $40 million for artworks regularly. There are huge amounts of money.

Things now feel so much more closed and bureaucratic. I kind of romanticize the idea of going out in the field with tools and digging a pit.

That’s why I feel lucky: that it was before people were telling you all the things you couldn’t do.

Mary Miss, Perimeters/Pavilions/Decoys (1977–78) in Nassau County Museum, Roslyn, New York. Photo courtesy the artist.

Mary Miss, Streamlines: Indianapolis/City as Living Lab (I/CaLL) (2015) in The White River, Indianapolis, Indiana. Photo courtesy the artist.

Mary Miss, Streamlines: Indianapolis/City as Living Lab (I/CaLL) (2015) in The White River, Indianapolis, Indiana. Photo courtesy the artist.

I used to do public transit advocacy in LA, and even to get a single bike lane, hundreds of people can work on it for decades and it still won’t succeed. It makes everything feel so impossible. So I admire how you’ve overcome that and have a lot of logistically complex built work in public and semi-public spaces.

I had a bad dream the other night that there was this big site in a public park, and everybody was telling me what I couldn’t do. I was walking through this open area and the person was telling me, “Oh, no, you can’t do that.” But at this point, the thing that is more interesting to me than making these larger constructions is all the amazing things about the specific place they’re in. I want other people to decode this landscape as well. That’s what led to my later work, where I’m focusing with mirrors on something in the distance and telling people what they’re looking at. So much of the work is to make available some content about the place because I really loved all that I was learning, and that’s what made me form the work the way I did.

We’re right down the street from South Cove (1984–1987), another major work of yours from this period. It’s similarly situated in water in an urban setting. New York state is planning a huge reconstruction of Manhattan’s shoreline, raising it to prevent storm flooding from rising sea levels. But unlike what’s happening in Des Moines, these preliminary plans seem to preserve your artwork.

Yes. And when anything needed repair, they would engage me. Landscape architect Kate Orff actually brought me in because Battery Park did not let me know they were doing it. But Kate got in touch and said, “Look, we’re doing this and we think you should be involved.” She paid me out of her budget.

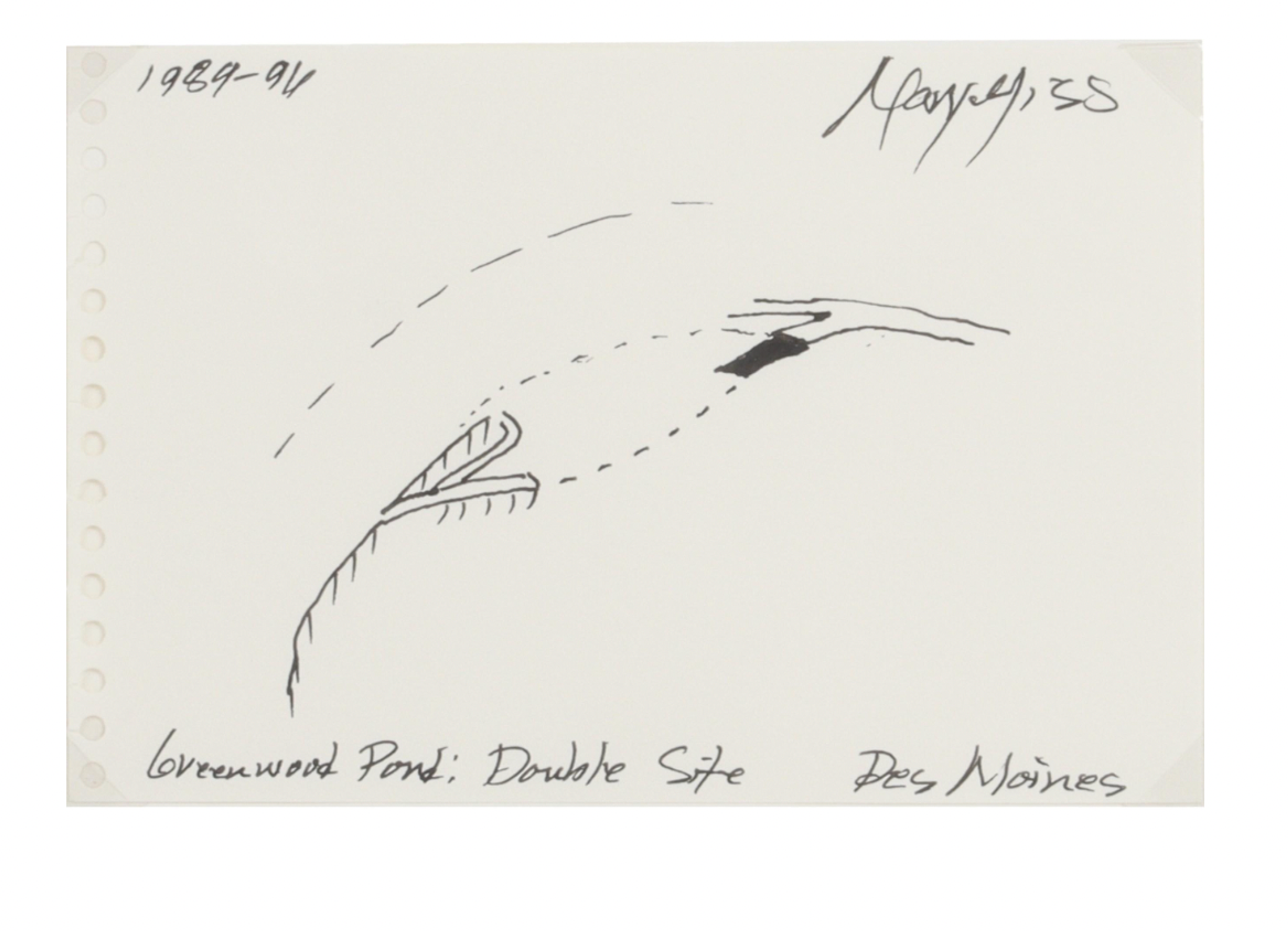

Drawing of Mary Miss's Greenwood Pond: Double Site. Courtesy Ripley Auctions.

Museums are constantly asking, how can we make an artwork that engages the community in a way beyond a heavy, heroic monument? Double Site can’t be reduced to a single image — it’s something you have to explore. It feels as if that intimacy and complexity has made the piece invisible to the museum as a legitimate artwork in their care.

When the project was first completed, I mean in the first decade or so, they were really caring for it. Somebody would go out there daily to check it out and see if it needed any repairs. I think that probably the subsequent people running the museum lost interest and just saw it as a park out there, so that by 2012, I got a letter from the director saying that it was in really rough shape. That’s when the Cultural Landscape Foundation first became involved and raised more than $800,000 to restore it. But nine years later, they’re saying the whole thing needs to be torn down. So what happened? A lot of people and other artists have been writing to support the work, trying to get the museum to change their course. I don’t know what will happen, but we’re going to find out. Even in this unhappy turn of events, it’s been really nice that value is being given to a project about the environment that involves the community, art, and environmental issues, and an artist really wanting to take on an active role. It’s proven that women can do work that’s worth saving. I think there was no value placed on it. And I think what must be shocking to the museum is how much value is now being placed on it by others.