Max Lamb, Western Red Cedar Chairs, 2021. Produced for Salon 94. Photos courtesy of Max Lamb ©

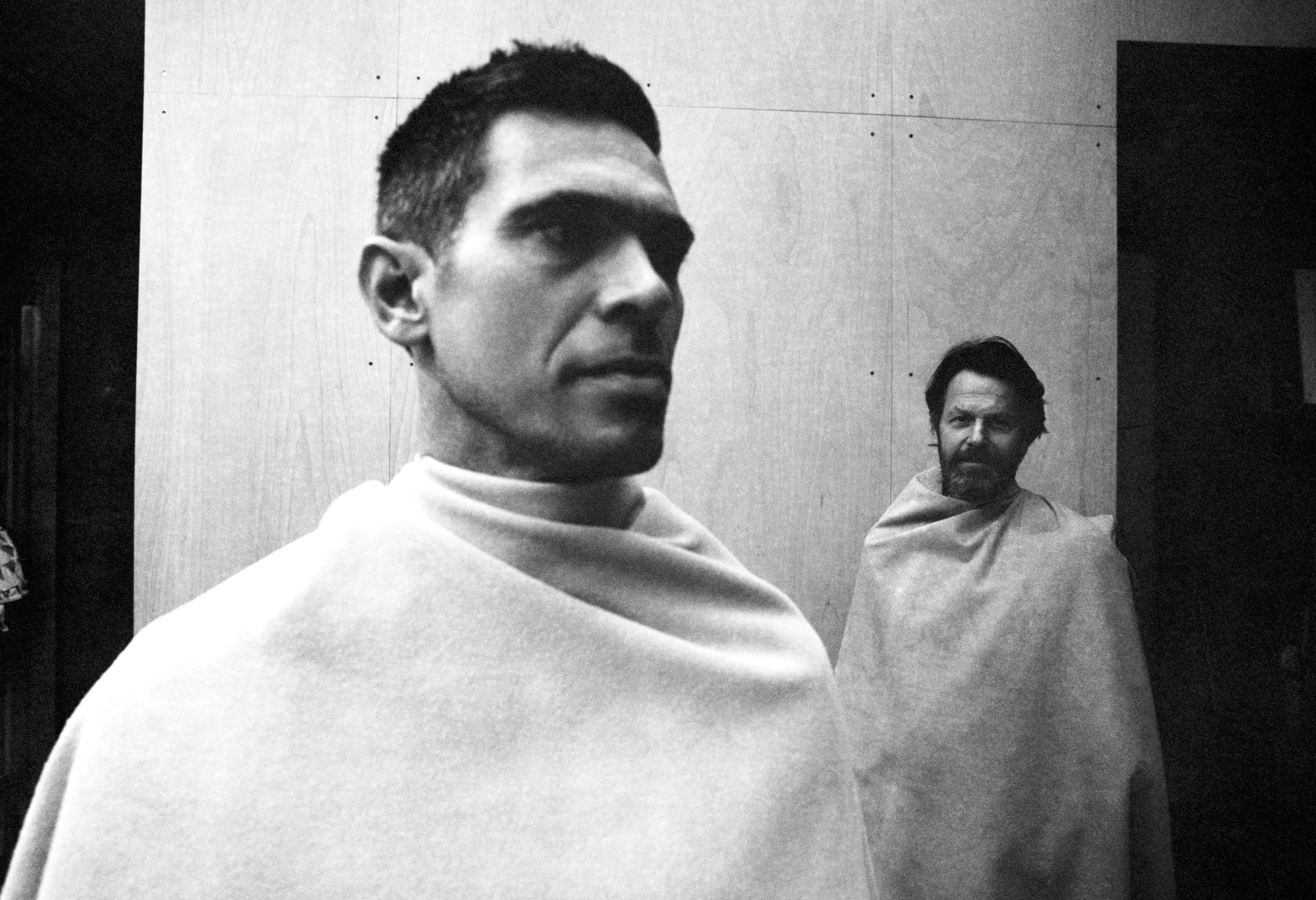

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that designers Martino Gamper, 52, and Max Lamb, 43, have both made projects with many chairs and strict, self-imposed creative limitations — Gamper was among Lamb’s tutors at London’s Royal College of Art (RCA), so something may have rubbed off. In 2007, the South Tyrolean-born Gamper made 100 chairs in as many days, creating playful Frankenstein one-offs from old unwanted pieces he found on the streets of London or rescued from friends’ homes; 14 years later, in 2021, the Cornwall-born Lamb made 60 chairs by hand in three days, carving the parts from slabs of polystyrene and coating the finished pieces in a high-gloss polyurethane, which emphasized the irregular texture engendered by the cutting process. The similarities and differences between their practices were brought out in these experiments — where Gamper’s work is more about the narrative and process, rejecting design’s obsession with the perfect object, Lamb seeks to respect the essence of the material, be it stone he carves by hand or pewter he casts in the sand on his favorite beach in Cornwall. As a fine-arts undergraduate in Vienna, Gamper worked for one of his tutors in Milan — architect, designer, and fellow South-Tyrolean Matteo Thun — before switching to design at the RCA under British-Israeli designer Ron Arad; Lamb also attended the RCA as a postgraduate (again under Arad), after which he spent time working for one of his tutors, British designer Tom Dixon. Both have studios in London — Gamper in Hackney and Lamb in Harrow on the Hill — and both are showing in New York this year: Gamper at Anton Kern (I Am Many Moods) and Lamb at Salon 94 Design (Echo). Though they’ve been close for almost 20 years, this is the first time they’ve sat down together for a joint interview.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: Martino, you have gathered discarded furniture from the street and repurposed it in 100 Chairs, If Only Gio Knew, and Furniture While U Wait. Max, you’ve spent days pouring pewter on a beach, chopped up a tree, transported and sculpted boulders, and made 60 Chairs in the back of a van. Can you both say something about your relationship to endurance?

Martino Gamper: I was asked to do a performance at Design Miami/Basel in 2007. I was already cutting up people’s furniture as a part of my practice and thought I might cut up something a bit more important. I remember my gallerist Nina Yashar [Nilufar] telling me she had these Gio Ponti pieces that she didn’t know what to do with. I asked her if I could use them because I knew the objects needed to have historical weight. She let me have them, and in the performance If Only Gio Knew I cut them up and made new ones in front of a live audience in Basel. The furniture was salvaged from the Hotel Parco dei Principi in Sorrento, Italy.

Max Lamb: 60 Chairs was about the idea of man as manufacturer, me as maker, and competing with industry. I made the 60 chairs on day one, sprayed them on day two, then photographed, labeled, wrapped, and packaged them on day three. So that was 60 chairs in three days. I had wanted to do a production batch for a long time. In fact, the stool that Hem now produces was my first self-initiated project where I was interested in making accessible work that wasn’t a one-off.

MG: It seems like you’ve always been interested in creating multiples or thinking about works in series. It seems that you like the process and that you don’t really do a lot of limited editions.

ML: I don’t do any limited editions. I’m very anti-edition. It’s such a classic avenue for a designer who wants to approach the gallery world. Rather than stopping at one or going as far as 100, they say an edition of eight plus two artist proofs.

Max Lamb, Western Red Cedar Chairs, 2021. Produced for Salon 94. Photos courtesy of Max Lamb ©

Max Lamb, Ali Bar Chair (prototype), 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and Salon 94 Design. © Max Lamb. Photo: Sean Davidson.

Max Lamb, Blob chair for Acne Studios Miami flagship, 2023; leather, polyurethane foam.

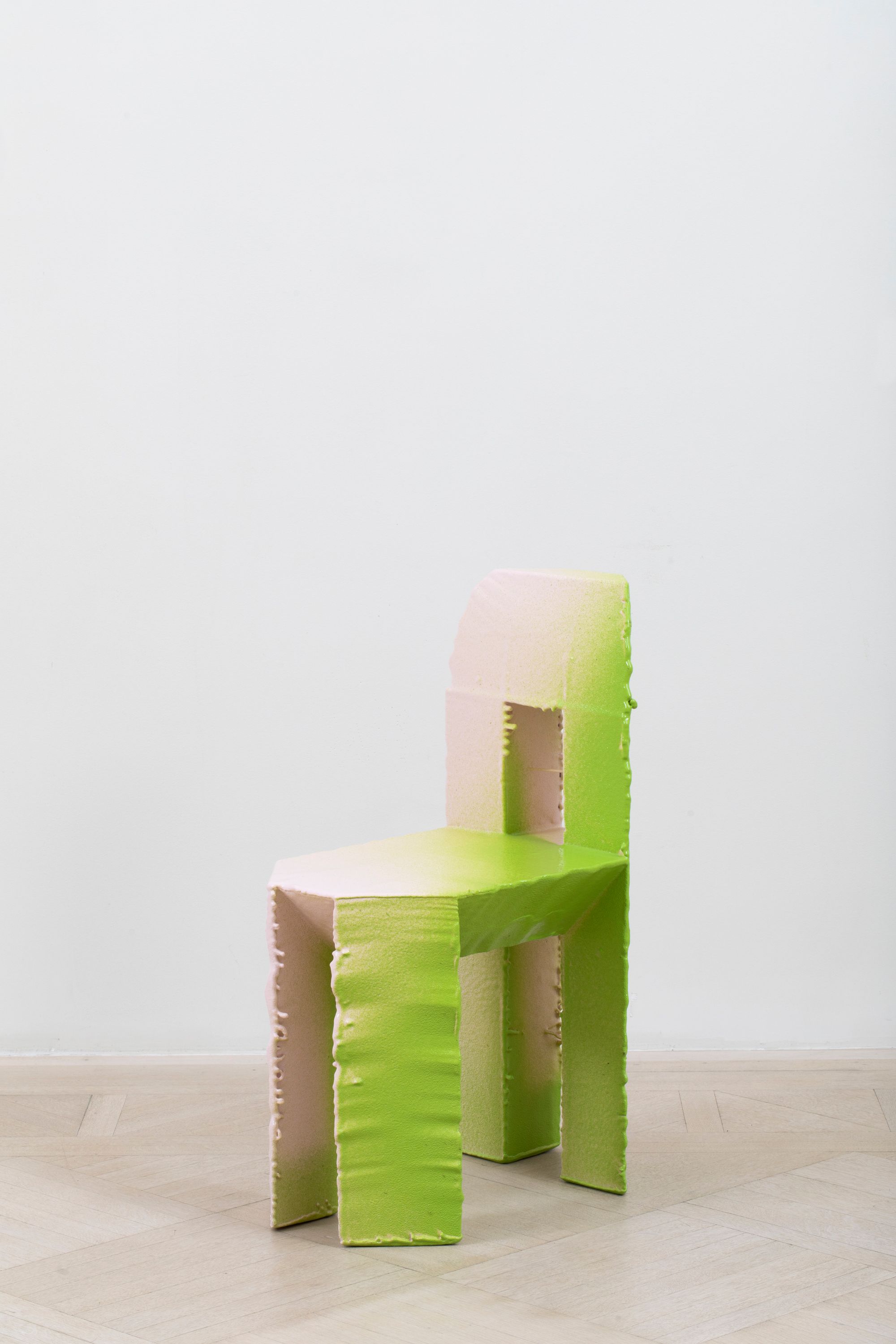

Max Lamb, Poly Rainbow Economy Chair, 2021. © Max Lamb. Photography by Clemens Kois. Courtesy the artist and Salon 94 Design.

Max Lamb, Chair No 1., 2010. Image courtesy of the artist and Salon 94 Design. © Max Lamb

MG: Yes, I call it a banana trick. Like when a vegetable stall puts out four bananas, and someone comes by and says, “Do you have any more?” and they’ve got extras under the table. Instead of creating value it’s creating artificial scarcity.

ML: There’s very rarely a reason why production of an edition should stop at eight or ten or 20. Making 60 chairs was an exercise based on time. It was a personal challenge, an ambition. I had already explored expanded polystyrene as a medium and I was pretty good at manipulating and transforming it. But I’d never made the same piece twice. That’s one of the beauties of that material, really — you can cut it and make a completely different piece every single time. So I thought, “Well, what if I was to make the same thing over and over again? How many could I physically make?” It was about human capacity and endurance. The cutting and assembly were pretty straightforward, but then came the spraying — I was at the mercy of a workshop whose facilities I used. I woke up at 4 a.m. and drove 200 miles. I started the process at 8:30 a.m. and by noon I was on the floor. I had to take off my overalls because I was perspiring so much while drinking gallons of water and tea. I’ve never run a marathon, but...

MG: You like to push yourself.

ML: [Laughs.] Totally, I’m an idiot.

MG: I was just telling Max about my experience working in Milan for all those industrial designers. I became disenchanted with the industry. We created so many designs, and I would say 80 percent of the projects weren’t realized. It was really disappointing. It’s the main reason I left and went to the RCA, to find and develop my own voice. I didn’t want to be making designs on pieces of paper and then just putting them in a drawer, you know? Everything is about compromise. When I was very young, I did an apprenticeship for five years as a joiner and cabinetmaker, but when I left, I didn’t touch furniture for years. After that I was working with ceramics in Vienna. I didn’t touch wood. I wanted to get away from that world entirely and become an industrial designer. I wanted to make products.

Martino Gamper, Lap-Dog, 2006; wood.

Martino Gamper, L’Arco della Pace bookcase, 2009; colored veneer, poplar plywood.

Martino Gamper, Box Cupboard with Chair, 2008; melamine-faced chipboard and re-used furniture elements. Courtesy the artist.

Martino Gamper, Middle Chair exhibition at the Modern Institute in Glasgow, 2017. Photography by Angus Mill.

Martino Gamper, Two-some chair, 2006; plastic, wood.

ML: As a reaction to the apprenticeship?

MG: Yeah, but at the RCA I remembered I had the skills to go to the workshop and realize my ideas immediately. Other people struggled. I had big fights with the workshop technicians — they were telling me I couldn’t do this and that, it was total rubbish. At one point I asked myself, “Why am I not making furniture? I know how to make it. I used to execute ideas, not just design them.” When I left the RCA and started making pieces, I wanted to build things that had meaning to me.

Do either of you think of your work as art?

MG: No way. It’s design.

To put the question another way: do you think people buy your chairs as furniture or as sculpture?

MG: I feel my work is a lot about me finding my interest in a project, not people giving me a brief and saying, “Hey, do this because we need it.” I make up my own stories and narratives. I think I approach the work through an artistic process rather than as preconceived design. I work like an artist, but the outcome is a design piece. You can’t go to an artist and say, “Hey, I was thinking, I really like your work, would you make this piece for me in green, blue, and yellow?” Most would tell you to get lost.

ML: [Laughs.] I see myself as a service provider. I make furniture for people who want furniture. Ideally there’s an equilibrium between the number of pieces I make and the number of people who want them. Hopefully it’s not too speculative. I’m not creating as an artist might in the hope that someone will buy the work. I don’t often produce stock. I mean, I do because I keep busy, and I don’t have queues of people wanting to buy my furniture all the time. I’m pretty good at just being proactive and active.

MG: But you set the brief.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

ML: In those instances, I’m setting the brief, but what I’m trained to do is to deliver on a brief. If you want me to make you a chair, a table, or a sofa, let’s talk. Ideally you are asking me because you already like my work. You’re not going to dictate what it’s like. You want a chair, so I’ll make you a chair. What’s important for me is that it’s my work and not yours, my ideas, not yours.

[Laughs.] Those are the ingredients; you don’t want to be given the recipe!

ML: Totally. And I have to be the author. I have to be able to put my name on it and say, “That’s my work,” and be proud of it. But of course, I am producing more than people initially want, which is why I depend on a gallery to find homes for my work. They help showcase and sell it.

How do you approach staging your work for shows?

ML: It’s a response to the work and the space. I’m thinking about a show in March 2024 at Salon 94 Design of potentially 160-plus archival works. It’s going to be such a puzzle because most of them weren’t made for a specific person or for a brief — they are an expression. Before I started teaching at the RCA, I used to do these little mini expeditions, four weeks or so, in China, Ireland, California, upstate New York — wherever I needed to go. Self-prescribed, self-initiated residential projects where I produced a body of work from the native materials of a place — quite large bodies of work that weren’t necessarily for anybody. Maybe in those instances, like Martino is saying, I was working as an artist would work, but the outcome was always grounded in function.

MG: Yes, that’s what I was saying. I think it’s more about the process for you than about where the work is going to end up. Initially it’s you, the material, and the process — that’s what generates a form. And then there’s another world where it goes into a gallery, but it’s meant to be sat on or interacted with, not just put up on a wall purely to look at.

ML: I’d say my work is about the material — not necessarily a pure material, though I am very singular, very mono-material. It’s funny, like Martino I was frustrated as a student at the RCA because of the workshops — there was a waiting list to get access to a technician, because we weren’t allowed to use the machinery ourselves. I went to the RCA wanting workshops, and I left having not used them: all of my work was self-produced outside the college walls or at another part of the college. I worked with laser cutters. I went to the beach in Cornwall to cast furniture. I created my own workshops and facilities. I’m not a very good designer, but I’m quite a good maker. My work designs itself through the process of making. It happens; it evolves. It’s like your work, Martino, just like when you’re creating your 100 Chairs. These pieces evolve. You don’t sit down and draw them.

MG: No, but that’s the whole point. For me it was about the frustration of having to sit down in front of a piece of white paper and come up with designs. I think sketching is an amazing process to put ideas down. Everyone draws for different reasons — some draw for beauty, others for reproducing exactly what they think. For me, it’s always been about putting my ideas down on the page so new ones come to me. If I don’t put them down, I’m going to get stuck. Why am I drawing something to then have to convince someone I can make it?

That’s my frustration in my own practice. I can map ideas on the page but lack the space, materials, or time to realize the work myself.

MG: Yeah, working with existing materials, I can look at it, cut, paste, because I have a pre-made piece. It’s amazing. I could never draw this. Could never come up with it. The object gives me instant feedback.

ML: [Laughs.] You can’t sit on a drawing.

MG: No, you can’t.

ML: They all feel the same.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

What are you referencing when you’re designing as you make?

MG: It’s a new thought, a new idea. You reference everything. [His phone rings.]

ML: I’ll answer the question for him. [Laughs.] He’s referencing the material. I would say that I also reference the material, but in a different way, because the pieces are self-generative.

But you pick the content and environment, then you respond.

ML: Yeah. But so does Martino. He picks up the remnants of furniture off the streets and he’s referencing those design details that somebody else has previously created. From Martino’s point of view, it’s a raw material.

MG: I was born in the 70s, but my cultural heritage is the 80s — especially the Postmodernism of Italy and Milan. At the time I had no idea what it was called, but I could see it as a new language developing in color and shape. And then in the 90s, I studied Postmodernism. I’ve always felt like I need to revisit those different styles and decades by combining them.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.

Can you talk about how you developed your design sensibility?

ML: [Laughs.] April, 2006: I was two months away from graduating. I hadn’t developed my signature then, but I was thinking, “How am I going to present myself to the world? How are people going to see me? They’re going to see me through my work. What is my work?” All of a sudden, I had this sense that I was about to be pigeonholed. I didn’t want to be. I wasn’t ready to graduate. I wanted to carry on experimenting. I was so stressed.

MG: Calm down, Max!

ML: I didn’t have enough time to develop the ideas far enough for them to stand on their own or be good enough to be representative of what I hoped I could become. So I decided I was going to make all of them. Most people made two or three things — I made nine pieces together with videos and a poster. I didn’t think any of the things I made were good enough to be called a product, but they were definitely valid and valuable as an exercise.

You were developing your own language.

ML: Right. I wanted to develop my own language, but I needed knowledge. And knowledge is about getting familiar with a material or process. I’d started carving this big cube of polystyrene into a chair as a way of model making because I didn’t know how to draw and design on a computer. I was sculpting this block as a prototype for a product, and Tom Dixon said, “But that’s your product.” And I was like, “That’s my product!” [Laughs.]

MG: I think it all comes down to knowing your strengths. I had to realize at some point that I’m not good at certain things. You realize that you’re not as good as other people in drawing, sketching, or using the computer, so you seek out formality. I had to learn to see my handicap as an advantage and think, “I may not be good at this but it made me great at improvising.” For a long time, I really struggled to accept that the way I was working with 100 Chairs was real design. By that time, I was working regularly and making good money. I made kitchens, ran my workshop, and did commissions for people. I realized that I was missing the satisfaction of the immediacy that I got from making the chairs in real-time. It was what I needed in my practice.

Martino Gamper, 100 Chairs in 100 Days exhibition, 2007. Photographed at 5 Cromwell Place, London. Photography by Angus Mill. Courtesy Nilufar Gallery.

Max Lamb, 60 Chairs, 2021; polystyrene. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94 Design. © Max Lamb

How did teaching at the RCA inform your practices?

MG: Teaching trains you to become very fluent in understanding other people’s ideas and translating them. People come and show you work, and you have to give immediate feedback. It’s important to contextualize the work in history and to understand what they’re trying to communicate with the idea. Ron [Arad] was really good at giving you an immediate response and placing the work in time and space. I feel so out of practice after not teaching for so long — you can feel totally lost, where your criticality becomes self-absorption.

ML: Right. It’s also because you’re forced to look back on your own practice while you’re teaching and critiquing other people’s work. It makes you very self-aware. And when you have a student who’s already quite confident or convinced about their work, it’s important to ask them difficult questions, which also makes you ask yourself difficult questions. You want them to question what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, and what they want to achieve. We have to help them look at the broader picture — look at what’s around them, what’s happening in the past, and what their peers are doing in parallel. If they want to continue on the same trajectory, they will, but it’s about giving them a little nudge. If the idea is good, they will go back to it because it’s the best way forward. This wasn’t during the iPhone days, so we’d recommend books and send them to the library for research. [Laughs.]

MG: Yes, it’s about contextualizing so they know what is out there as well. I think it’s about framing it in history. Where does it stand? Because there are only so many ideas in the world. We all have the same sources of inspiration. Now it’s worse with artificial intelligence, algorithms, and social media.

In the context of today’s socioeconomic climate, what does design mean to you?

MG: It’s a set of materials, processes, tools, and narratives.

ML: It’s transforming a piece of material into something that serves a purpose regardless of how ambiguous its function may be.

Max Lamb and Martino Gamper photographed by Bolade Banjo for PIN–UP 34.