Martine Syms photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Martine Syms photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Artist Martine Syms grew up in Los Angeles, but her rise to stardom is far from the typical Hollywood nepo baby story or one sprinkled with Disney fairy dust. Obsessed with moving images from a young age, Martine spent her days visiting second-run movie houses across Tinseltown or watching countless hours of television. She channeled this Gladwellian 10,000-hours of expertise into directing the first episode of her video art TV series titled She Mad (2015–22). The protagonist, also named Martine, is an overachieving stoner and graphic designer living in Hollywood, with dreams of becoming a famous artist. The series begins in 2015, which is coincidentally the same year that the paths of the real and fictional Martines began to deviate substantially, with the real Martine opening her first solo show at Bridget Donahue in New York and being selected to participate in that year’s New Museum Triennial, followed by numerous prestigious institutional exhibitions across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. In 2022, Syms presented her first feature film, the The African Desperate, based on her experiences in the Bard College MFA program, starring her friend and fellow artist Diamond Stingily. Impassioned for fashion, Martine has developed a lucrative side hustle directing advertising films for Prada, Nike, and, most memorably, a 30-second spot featuring a pregnant Rihanna for Pharrell’s 2023 Louis Vuitton men’s debut. This fall, Martine has one of her largest exhibitions to date: Total, a solo show at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, which brings with it the inevitable conflicts with art institutions in general and, in particular, the desire to drill down into the dominant presence of the building’s architect, Rem Koolhaas.

Martine Syms photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

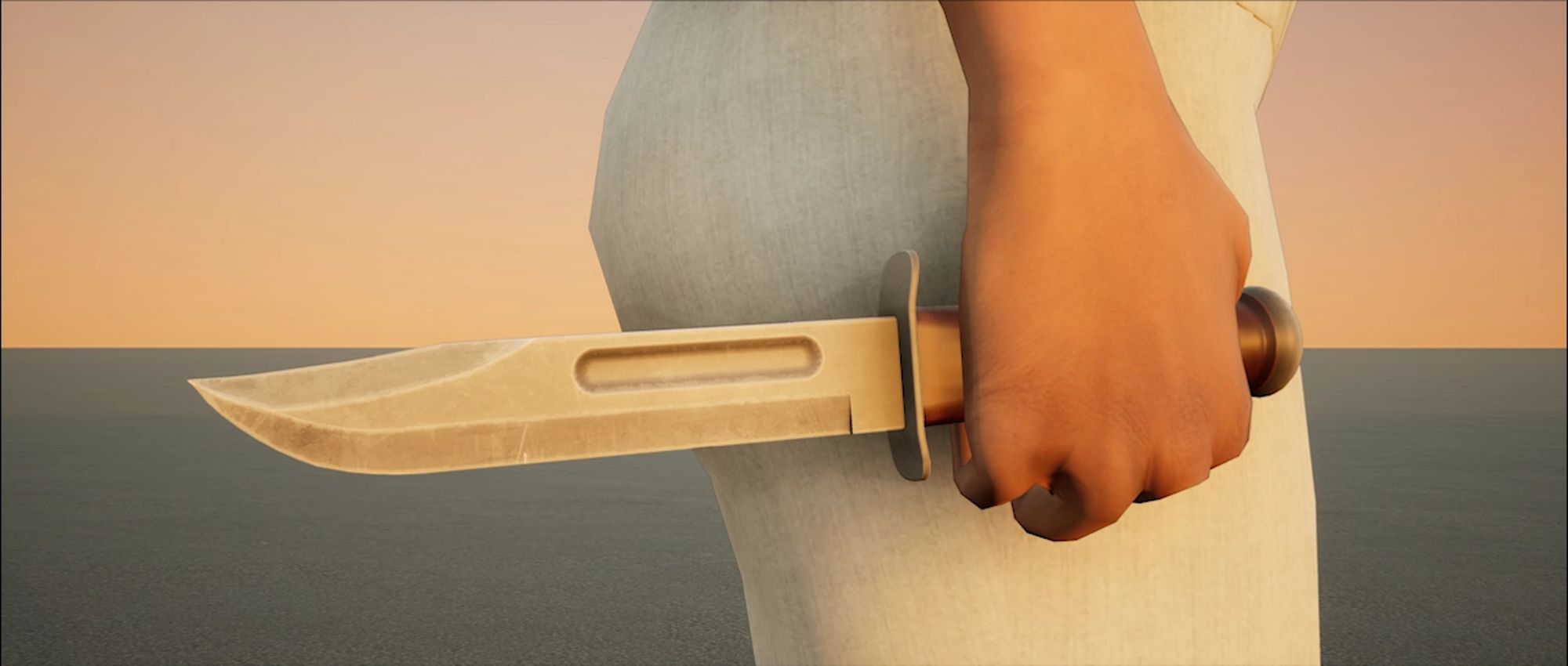

Martine Syms, installation view of Loot Sweets at Bridget Donahue, 2021. The exhibition screened DED, featuring Syms’s avatar created using a 3D scan of her body. In this barren landscape, like a digital purgatory, Syms’s avatar continually dies and is reborn. Photography by Gregory Carideo. Additional courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York.

Jordan Richman: Did growing up in Los Angeles, with its proximity to fabled Hollywood, originate spur your desire to make films?

Martine Syms: Probably in some ways. My parents weren’t in the film industry, but people who lived on my street were — one neighbor was an actor, another one built sets for soap operas. I remember there were always pieces of sets in his workshop. And then when we were younger, my brother was an actor. We were all homeschooled, so we all did what everybody did, so that meant all of us were acting, although I wasn’t very good at it. I didn’t get cast for a lot of stuff. [Laughs.] but I would work as an extra, or I would be on set with my brother. I always liked when you could identify where something was shot. My sister’s best friend’s house was in 90210, so there were always tourists in front of it. I liked how I knew what was real and fake.

You had these kind of glances into the industry, which made it seem like a real profession and not just nepo babies and Disney fairy dust.

Exactly. A lot of people around me were working actors, or union grips, so I knew it was as a job that you could have. Once I became a teenager, I spent all my free time going to movies. There were a lot of cool theaters in L.A. at that time. There’s a resurgence of it now, which is nice, because for a chunk of time here recently there was nowhere you could go to see an old movie. Growing up I would go to New Beverly or the Egyptian or to midnight movies. I would go see movies at a discount theater near my house. I stopped going to school when I was around 15, so I had a lot of free time where people my age weren’t around, and I went to see so many movies. [Laughs.] I’ve always been interested in film. I remember watching The Crying Game and Basic Instinct as a child. I remember being like nine and moved by Pedro Almodóvar’s All About My Mother, and I was obsessed Penelope Spheeris’s punk documentary The Decline of Western Civilization in seventh grade.

Portrait by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

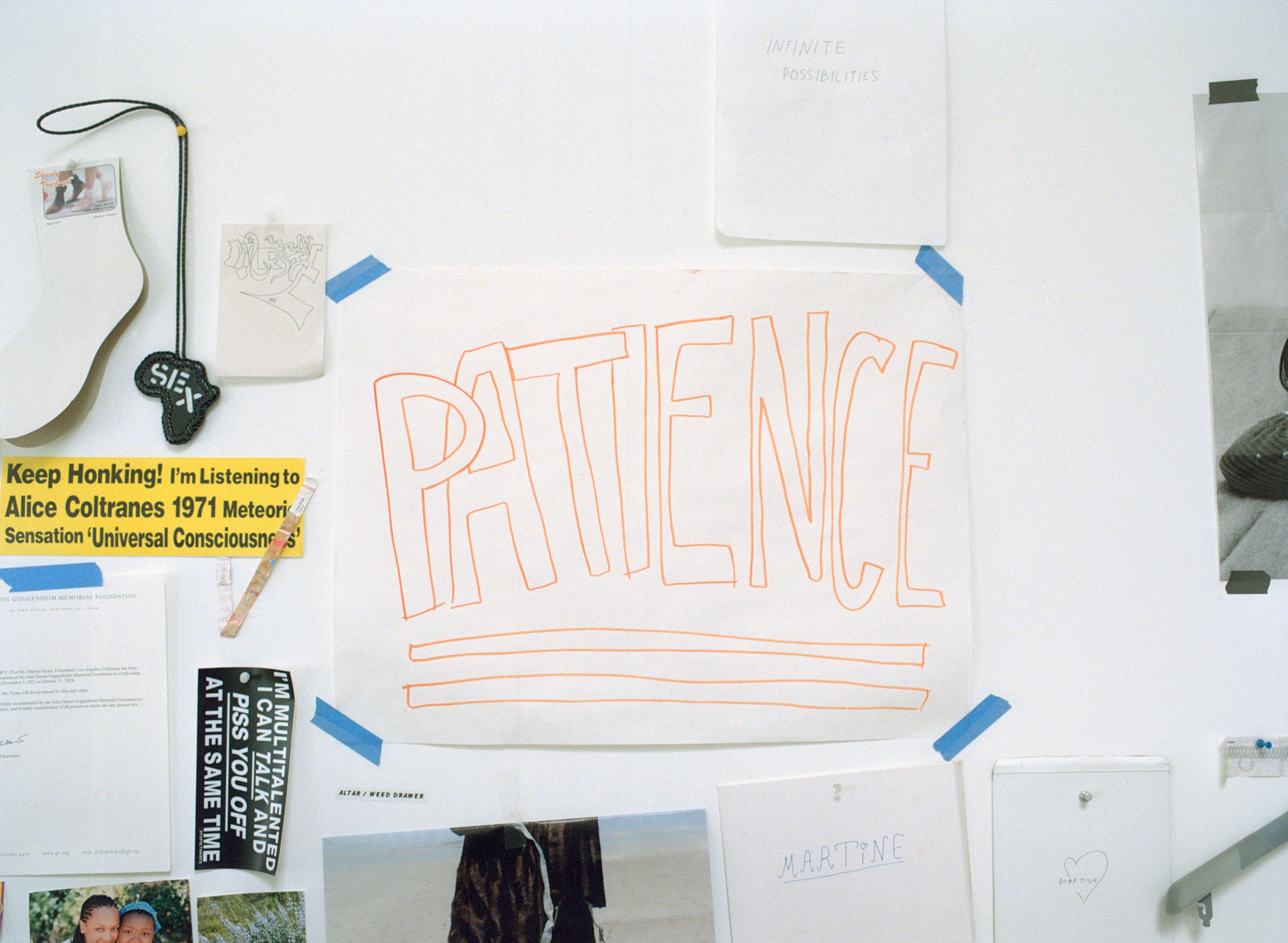

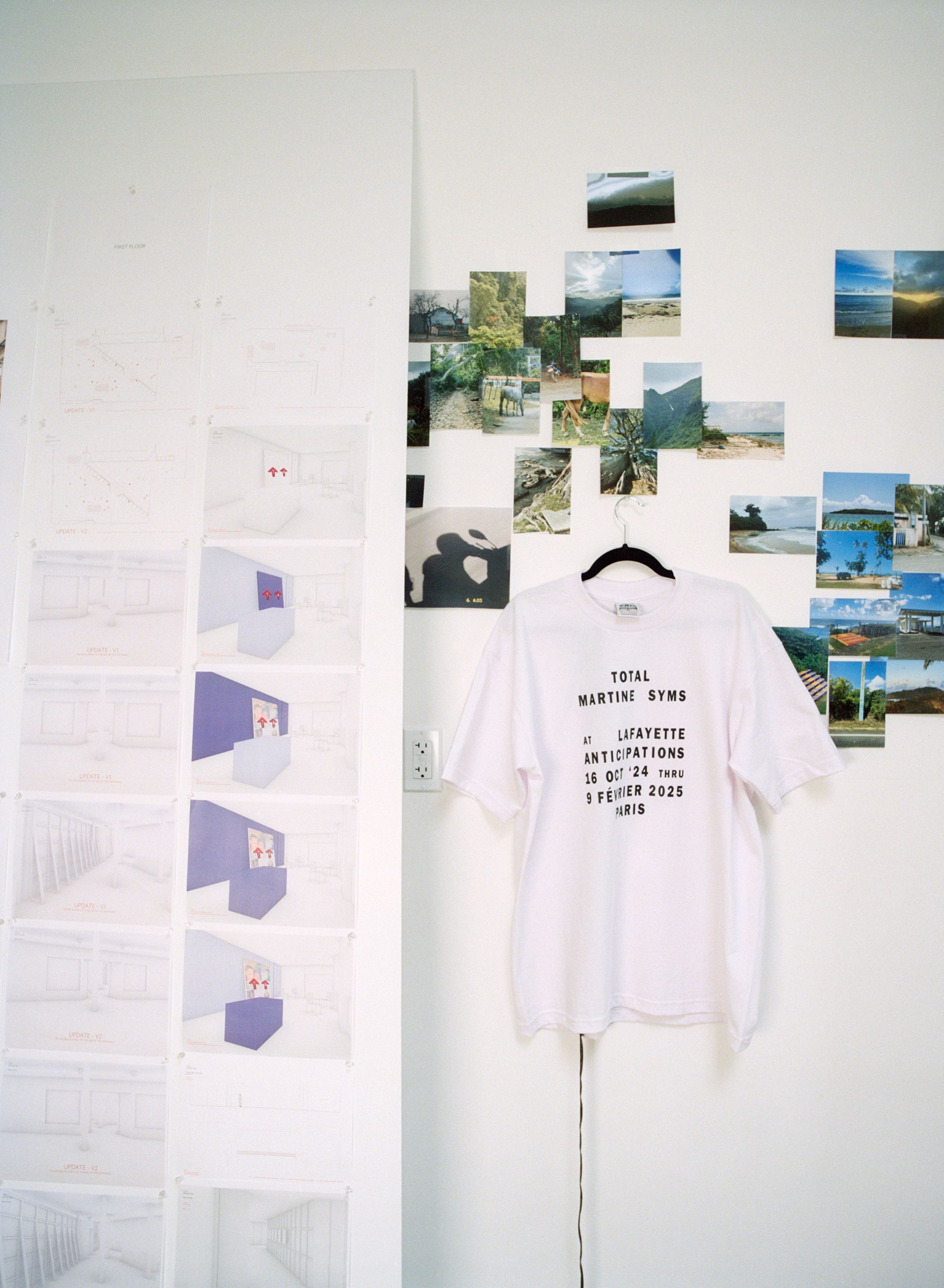

Martine Syms’s L.A. studio photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

When I first moved to L.A., I remember it would get so hot in the summer that I would go to that discount movie theater, Academy, in Pasadena just to cool down. Does it still exist?

It’s still there! It still has the Wednesday special: popcorn, hotdog, and two tickets for $10. Cheapest date in L.A.

How would you say mass media shapes and frames our identities and cultures?

I was thinking about this the other day when I was trying to describe my work to somebody. I was going back and forth in my mind over whether I should say “mimetic,” like the copy, or “memetic,” as in the meme, the cultural unit that gets repeated. Both are about the copy, but I decided on mimetic, which was my first thought anyway. Things spread through replication, whether that’s systems or structures. Isabel Wilkerson writes about how Nazis based their race laws on Jim Crow. Or like, R&B’s influence on K-Pop, which is a direct result of Black soldiers bringing their music to Korea during its American occupation. Or how Palestinian rappers use hip-hop to express alienation. I’m really interested in that mimetic quality, and my work is a lot about repetition, taking a form, an image, or a phrase that’s been stuck into my head and putting it into the world. I think about this with language a lot right now, because it feels like everyone talks the same. People call it brain rot. I miss regional slang! That’s what I think about with my work too. In my video series She Mad, with each episode I was trying to find something that happened both in film or television history and in my own life. I like merging those two stories. I think that’s part of that mimetic desire. We don’t create the desire; it’s implanted in us. Wanting is beside the point.

Martine Syms’s L.A. studio photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Martine Syms, installation view of Neural Swamp / The Future Fields Commission, 2022. The multichannel video installation uses humor and horror to investigate what it means “to be Black and a woman in a hyper-digitized world.” Photography by Joseph Hu. Additional courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

The first video work of yours I remember seeing was She Mad, the series you began in 2015 that took the form of a semi-autobiographical sitcom. Is the title of the first episode, “A Pilot For A Show About Nowhere,” a reference to Seinfeld, which was famously “a show about nothing”?

It’s Seinfeld mixed with a quote from Amiri Baraka’s autobiography. He says, “If we had known what faced us, some of us would’ve copped out, some would’ve probably got down to study, as we should’ve, instead of the nowhere shit so many of us were involved with.” The incredible Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, who I knew from her publishing project BLACKNUSS, put me on in her [2011] book Harlem is Nowhere. I’m getting up to nowhere shit. The book also references poem by Langston Hughes that describes the distance from nowhere to elsewhere. That idea stuck with me for a while. And I’ve always loved Seinfeld, ever since I was a kid. My parents hated it so much. Like, hated it. [Laughs.] So I was thinking that if I was going to make a show about my life, that’s what it would be — the two of them together.

Do you think partially you enjoyed watching Seinfeld more as an act of rebellion because your parents hated it?

Yeah. I wouldn’t have been as into it if they didn’t hate it so much. That’s also why I watched a lot of MTV and The Simpsons; they both had a charge to them, because I wasn’t supposed to watch those either. The writing is also very good on The Simpsons and Seinfeld. I had taste, Jordan!

The protagonist of She Mad is also named Martine and is an overachieving, stoner graphic designer who lives in Hollywood and wishes she was a more important artist. How are you and the character similar?

At this point, the real and fictional Martines are very different. But in 2015, I was pulling from my own life experience because I was exploring representation. I was envisioning a fictionalized version of my own life in the traditional sitcom format, which was somewhat outdated in 2015, but which I felt was being reinscribed on Instagram. Not only were people presenting an idealized version of themselves but they were also actively writing fiction, and the production was high quality.

Martine Syms, installation view of Dialogues: Irena Haiduk + Martine Syms at ICA Virginia, 2019. Additional courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York; ICA Virginia; and Technology Residency at Pioneer Works, Brooklyn.

Martine Syms, installation view of SHE MAD: Season One at Bergen Kunsthall, 2022. Photography by Thor Brødreskift.

People really began hyper-curating their online persona around that time.

I always use the example of backlighting. Prior to late aughts, that was an idea from commercial photography that your amateur photographer wouldn’t have been concerned with. People were aware of making a “good” image. They were finding their light. And I thought, what if I turned that performance into a television show? That’s the Hollywood slimeball in me. [Laughs.]

And when did the fictional and real Martines diverge?

Intro to Threat Modeling, which I made in 2017, when I started working with AI and AR. I had just finished this complicated AR app when ARKit dropped. It became much easier. I already had a 3D model of myself that I kept improving. I was learning ARKit and Blender with it. Teenie, which is what I call the model, became its own thing. “Threat modeling” is a cybersecurity concept, but I was using it the way that there are fit models. Teenie is a threat model. My friend Colin Self gave me another term recently: “tulpamancy.” It’s a techno-spirit, a thought form turned entity.

Martine is sentient…

She is actually. Okay. Semi-sentient. There are a few different models that I use to create Teenie. In my exhibition Grand Calme [2018] you could text with it. I had two AI fellowships where it got built out more. I was working with OpenAI tools from around 2017. I wanted to make a copy of my voice. By the time of the exhibition Neural Swamp [2022] she was speaking. ML/NLP gets better as you run the program. By the end of the run at Philadelphia Museum of Art, some of the output was beautiful and poetic. I was like, okay, Teenie! [Laughs.]

Martine Syms photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Martine Syms photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

Martine Syms’s L.A. studio photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.

And why is Martine mad?

Isn’t it obvious? To quote Solange, there’s a lot to be mad about. What makes me the maddest? Honestly, other people. I hate people. I’m mad about the intractable structure of systematic inequity at the root of capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and the overall destruction of the natural world, including us. I hate how war makes money and how it feels impossible to get away from the military industrial complex. With the threat model, I wanted to make a seductive image but then I kept going back to the stereotype of the angry Black woman. I thought that was fun. A fucking harpy siren banshee. There was also a meme circulating at that time that said, “Oh, she mad, she mad.” And I was like, I am actually so pissed right now. Sometimes I get so mad that it becomes funny to me. I was working with it. That’s when the avatar became really angry and violent and less like the sitcom version. Time for some dime store psychoanalysis, but if you’re trying to present something, there’s also something you’re trying to hide. I wouldn’t have articulated it that way when I started, but that’s what I was working through. Around the time of Threat Model, Teenie became a shadow. I was training the model on my trauma. Part of the text can be read in my [2020] book Shame Space, which readers will have to find secondhand. I hope it gets republished one day.

There is certainly a lot to be mad about. Museums can also often be conflict zones. Have you experienced this in your career?

Yes, quite regularly. [Laughs.] It’s probably one of the most major conflicts in my life. Where do I start? There’s the tax shelter of it all, the money laundering of it all, which is at odds with making good, challenging or exciting artwork. Then there’s the collection/acquisition side of it, which like any other archival, history-producing process has a structure you have to fit into. If you don’t make the kind of work that easily fits into the museum’s system, then you’re going to have a struggle. And then there are all the other problems that institutions have.

Does that make you mad?

It pisses me off sometimes, because I’m constantly working with museums. I’ve made some museums mad as well. I feel like over the last decade-slash-always, people have been asking, “What is the museum for?” Over the past twenty years, I’ve come to understand who and what they’re for and the art part of that is quite small. I don’t struggle with it anymore.

Then why work with institutions?

I love art, so I still have an experience with it. It’s the place where I do my work. I’m committed to coalition politics. The museum has the same problems that you’ll find in the rest of the world. They’re available to change at that scale. I also love the format of the exhibition. I don’t always work exclusively with institutions. It depends on what I’m doing. I’m no longer surprised by who’s on the board. It’s doing what it was designed to do. I went to a museum school [School of the Art Institute of Chicago], so I spent a lot of time in the museum. Or even the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is one of my favorite museums. That’s part of why I wanted to do the show there [Neural Swamp, 2021], despite the challenges of trying to make an insane show at a museum that’s so encyclopedic. Museums create canon, value and history, which are always exclusionary. There’s no other way for it to happen. Have I had many fights in the museum? Yes. When I have an idea, I want to see it through. I don’t like when the institution’s answer is an immediate no. I’m like, let’s try and figure it out.

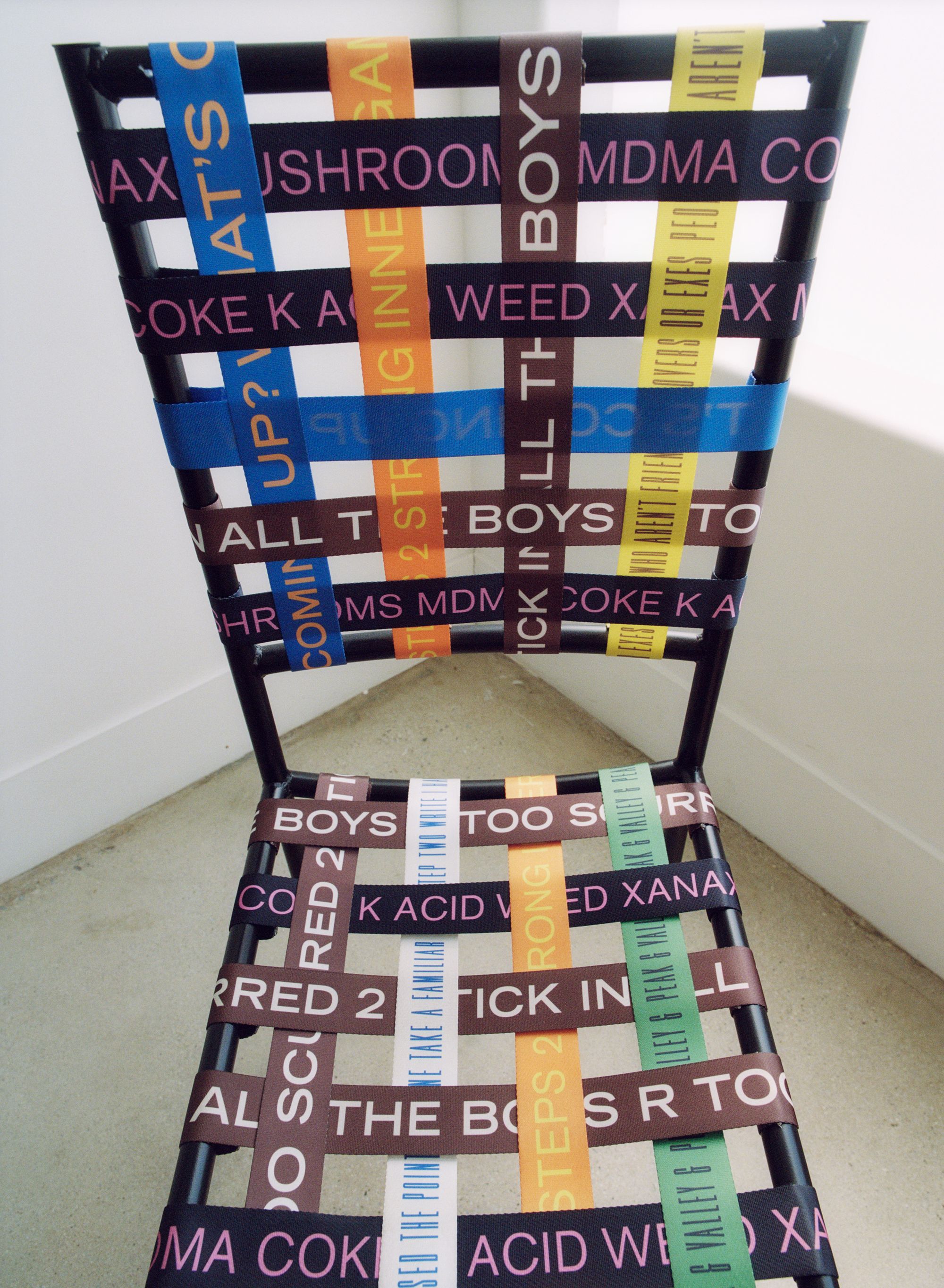

Martine Syms, film still from SHE MAD: Laughing Gas, 2016; 4 channel video installation, wall painting, laser cut acrylic, artist’s clothes, 6:59 minute loop. Inspired by Edwin S. Porter’s silent film Laughing Gas (1907), which follows Mandy, played by Bertha Regustus, as she walks through the world after receiving nitrous oxide at the dentist’s office, the pilot episode of SHE MAD features Syms playing the role of “Martine” through improvised vignettes that include security camera split screens, found clips, and internet GIFs.

Syms based her first feature film, The African Desperate (2021), starring her friend and fellow artist Diamond Stingily, on her experiences in the Bard College MFA program. Additional courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York.

Martine Syms, still from DED, 2021; video, 15:47 minutes.

Martine Syms, still from DED, 2021; video, 15:47 minutes.

When they say no, what is it that you’re most often coming up against?

Budget.

But then isn’t that just an opportunity to launder more money?

Exactly. Fundraise, fundraise, fundraise!

I’ve heard from other artists who have also exhibited at Lafayette Anticipations that the museum, designed by OMA, is very challenging architecturally and spatially. Did you find that to be true?

Yeah, it’s hilarious to me because it’s like, we all knew this was going to be an art space, right? [Laughs]. Rem Koolhaas’s presence is quite strongly felt in the building, too much so in my opinion — which has been a source of conflict for me while working on the show. OMA made a lot of weird decisions. I like the idea of the moving floors, but it would be cooler if they could actually move while being placed in different positions. A friend of mine, Neïl Beloufa, said that for every starchitect museum he’s in, he tries to permanently damage it in some way. Maybe that was a secret.

Martine Syms, installation view of Fact & Trouble at ICA London, 2016. Photography by Mark Blower. Additional courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.

How are you going to permanently damage Lafayette Anticipations?

I don’t know yet. I’ve been trying to figure that out. I think I’m going to drill something into the floor. Carve my lovers name in the bathroom. Or maybe I’ll make my mark in the stairwell.

Hot. You also had your own experience running an arts space back in Chicago, right?

Yeah, I ran Golden Age for five years [2007–12]. It was technically a book shop, but it was also a gallery and music venue. We did a lot of music shows and hosted exhibitions with artists. We also published artist zines and books and did screenings and talks. Basically, if somebody wanted to do a thing, most of the time we’d say yes. We did one of Alex Da Corte’s early shows. I was just looking at pictures of one of the shows we did with another artist. He made an ice luge that you drink alcohol out of, but instead it was just spewing blood. I forget what kind of blood we got from a butcher. I remember there was a big party that night, and the luge got totally disgusting. The blood coagulated and dried and the artist left before it was over, so I had to clean it up.

What has stayed with you from the experience of running the space ?

The people. I met so many people through Golden Age. Dare I say community! May I be so bold? I had strangers staying at my house all the time, artists, bands, whatever. It was so much fun.

Martine Syms, Ate or Act III, 2023. This short video was displayed on a custom LED screen encased in a yellow powder-coated box, bridging moving-image and sculpture. Photography by Katie Morrison.

And one those people was the artist Diamond Stingily who starred in your feature film The African Desperate.

Yes, Diamond! She would come into Golden Age at least once a week. I always loved seeing her and we became friends. She was always performing and I asked her to be in my work. She’s been in several of my art videos. Later, I was living in New York, and I asked her to shoot Notes on Gesture [2015] with me. She was on some Marilyn Monroe shit — “Buy me a one-way ticket!” [Laughs]. After that we became very close. We still laugh about that shoot.

I know you also love clothes and often collaborate with fashion brands on commercials and other projects. Who’s more intimidating to work with: Rihanna or Mrs. Prada?

Honestly, they’re both chill. People don’t believe it. Honestly, they’re both chill. People don’t believe it. Okay maybe not chill, but I’m not chill either. I’m so high maintenance. They are curious, creative geniuses. Fame doesn’t intimidate me. Both of them were cool as hell. Mrs. Prada was like, “Oh, you’re a Taurus. Me too.” I was like, period. But l just feel like it’s easy. Don’t be on bullshit. Come correct. Be prepared. You can’t go in there feeling weak or less than someone else. You have to come as an equal. I know what I’m doing. I love being on set. Rihanna’s seven hours late? It’s fine. We’ll figure it out! I can’t wait to shoot my next movie. I want to work in that chaos all the time. That would match my energy actually.

Martine Syms’s L.A. studio photographed by Zoë Ghertner for PIN–UP.