What are the issues in architecture? And how are they structural?

In my teaching of architectural history, I always try to be very clear that the body of knowledge that we are going to learn about emerged in the West. Architecture is a specifically Western practice of building that originated in Europe — it’s not how people around the world historically built their lived environments, which is important to recognize. One of the West’s brilliant tricks is its episteme and how it universalizes. Architecture, as a set of concepts applied through the work of architectural history, draws all these other traditions of building under one umbrella — one that begins with the concept of building and then uses modes of representations to make buildings, including other modes of abstraction like finance and surveys. That’s a particular Western framework. The Renaissance coincides with 1492, when the colonial project began, and you can’t help but think that somehow the emergence of architecture is running parallel with a colonial project influencing aesthetics and technology. All those aspects come to form what we generally understand as architecture. But they are also deeply embedded in capitalism, which is explored in the writings of both Ken Frampton and Manfredo Tafuri. You can’t understand architecture without understanding capitalism. If racial difference is another ideological paradigm that comes into practice in parallel with capitalism, how could it not be a part of the ways in which architecture develops its own body of knowledge, its own rules, and its own understanding? These building practices that emerged in the West are now applied worldwide — similar to how the English language has spread globally through the Internet — but what kinds of implications are there when that becomes the lingua franca of this interface?

As well as teaching architecture, you have your own practice. What does architecture mean in the context of an institution and what does it mean when you encounter it out in the world? Are those two different concepts or are they one and the same?

I think they’re one and the same. If you’re talking about the learning institution, it produces the knowledge and passes it on to a group of people. But institutions are also dependent on architecture for their own functioning, because schools occupy buildings. Reinhold Martin’s recent book Knowledge Worlds: Media, Materiality, and the Making of the Modern University does a really good job of pointing out architecture’s role in literally creating the scene for that kind of unfolding, and how its technologies function as a media machine for how we learn. But I think architecture is sometimes hard to detect. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin writes about film, and towards the end says, “Architecture has always represented the prototype of a work of art the reception of which is consummated by a collectivity in a state of distraction.” We’re not consciously focused on architecture, and yet it has the same kind of media presence as film, and therefore, for Benjamin, it could be revolutionary.

Who are you reaching for and talking to with your work?

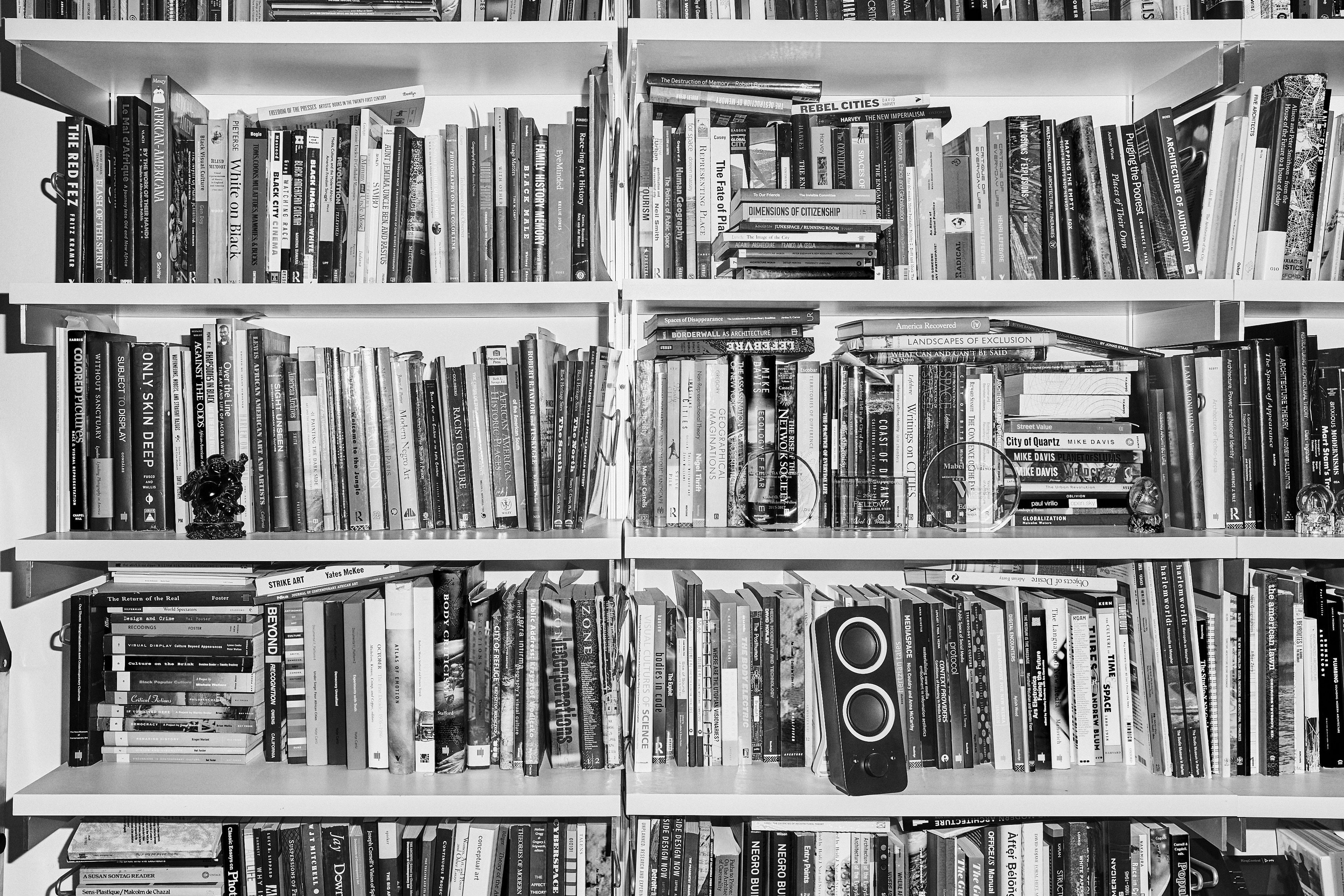

It’s evolved over time. I had specific interests in understanding why, in my architectural education and professional experience, my own history of place and family wasn’t represented. It was somewhere else and external to architectural discourse. As I’ve tried to draw out that absence in different ways, I’ve developed multidisciplinary ways of exploring it, through writing projects, art, and a curatorial practice which has taken on many valences. In doing that, the work has cultivated many different audiences, which has been a surprise for me.