Lotte Andersen photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

Lotte Andersen photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

Artist Lotte Andersen’s installations are a bricolage of found pop culture ephemera, sound, video, and immersive, haptic sculpture. Plumbing the depths of group dynamics and the physiological textures (and fragments) of the greater social fabric, Andersen seamlessly memorializes her own family history and personal experiences with the sociopolitical zeitgeist. Her art career, thus far, has been one of an organic and nonlinear path. Growing up on London’s Portobello Road with a DJ father and photographer aunt, Andersen became known for the exultant MAXILLA parties she’d throw throughout the city, which she later memorialized in her seminal immersive video installation Dance Therapy; Do it once do it right (2017) — an unabashed and celebratory exploration of communing on the dance floor. More recently, the Mexico City-based Andersen exhibited her puzzle sculptures and sound works in the solo show Crowds and Crate Diggers at New York’s Helena Anrather gallery. Below, Andersen discusses her compellingly dextrous life and work, which arrives at nuanced reflections on self, community, and what it is to “belong,” both interpersonally and on a greater global scale.

Installation view of Lotte Andersen’s Crowds and Crate Diggers at Helena Anrather. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

Keegan Brady: You live and work in Mexico City, but you just wrapped a show in New York — have you ever lived there?

Lotte Andersen: No, I’ve never lived in New York, although a lot of my friends do. When I was in my 20s, many moved over to go to school, so I spent a hefty amount of time visiting or doing internships. When I was younger, I wanted to work in fashion, so I spent some time working for a company called Salvor Projects, before I went to begin my degree in 2008. It was over the period when the stock market crashed and Obama was elected. That trip really changed the course of my life, actually.

In what ways?

Well, I was born in London, and I think that the youth in the U.K. had not necessarily been as politically mobilized as our U.S. counterparts. I was beginning to understand how money works in a really practical sense because of the exchange rate between the pound and the dollar, which was changing every day, along with understanding how directly our lived experiences are hinged on the politics that we live through.

And then after that, you attended university in London?

Yeah, after that I came back home and I studied for a degree in fashion design [at Kingston University]. I was on the fence about the whole thing, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to study menswear or womenswear. I had previously interned at Alexander McQueen and was interested in art direction, which led me to work with Tyrone Lebon on a video for Mount Kimbie. I dropped out in my second year and ended up working in tailoring at John Pearse for 4 years. I found it satiated [the urge for] practicality — this idea of making one of everything, and also making one suit extremely well. It also had to be functional for the person or the body that I was building it for.

Lotte Andersen photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

Do you feel that your experience tailoring informed your art practice?

Hugely. So much about tailoring is [that] it’s a very intimate space. You are measuring inside people’s legs, so there’s a part of you that has to be quite chatty and keep it light, and another part that works as a designer — and by that I mean you might have a client coming to you saying that they want an all-black kitchen, but practically speaking you know that they don’t actually want an all-black kitchen [Laughs]. You have to ask very particular questions. It’s a social practice, being a tailor. There is a dance that happens between the client and the tailor, and you hold all of their secrets and information whilst you are bringing this garment [to fruition]. I can also see shapes, and gestures in my collages which remind me of tailoring blocks. I’ve found myself incorporating so much of that life into how I cut and arrange paper in my collages.

I'd love to talk more about the MAXILLA parties that you used to throw in London in the mid-2010s. What was that like?

In hindsight, it was such an extraordinary and wild moment. I’m not a hedonist — I’m quite a dork. I grew up in this cool 90s environment [with my parents], and I was around parties when I was very young. I was aware of the power of having these mixed creatives in the room, all from different disciplines, and the legacies and collaborations that would emanate from this. I just fell into making parties and loved it. And because my dad DJ’d, I always knew the importance of a sound system or the potential of choosing the right sound in the room. I think I had a good sense of how to aggregate all the things that you need: a venue that has places to smoke, places to kiss, places to dance, another place to talk. I always said a great party would have to function like a house party because it needs nooks and crannies for things to happen. I also grew a sense of space and how to deal with groups of people. It’s the same now with sculpture and performances. I can go into a space and feel it.

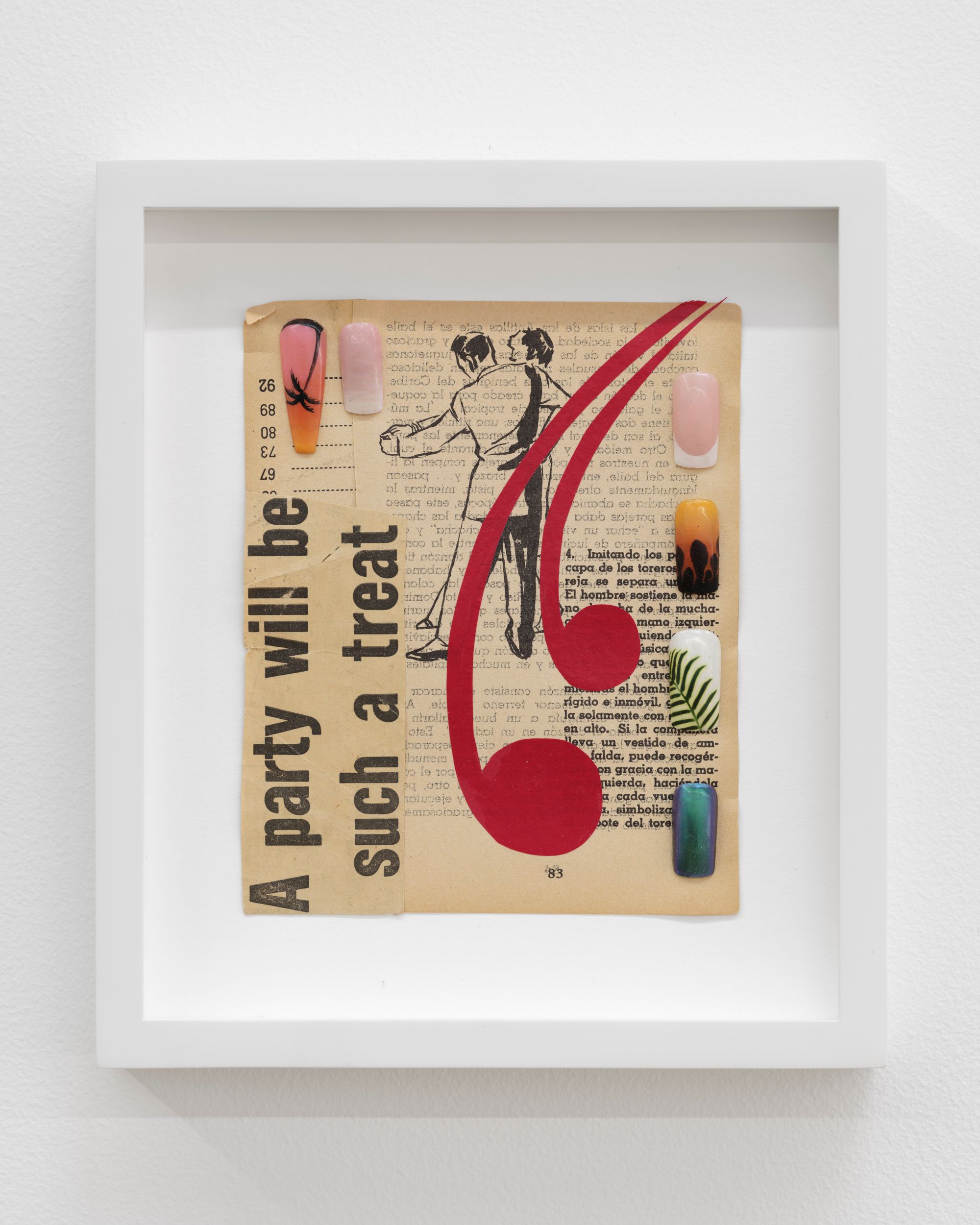

Lotte Andersen, Typical Girls, 2023, in Crowds and Crate Diggers. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

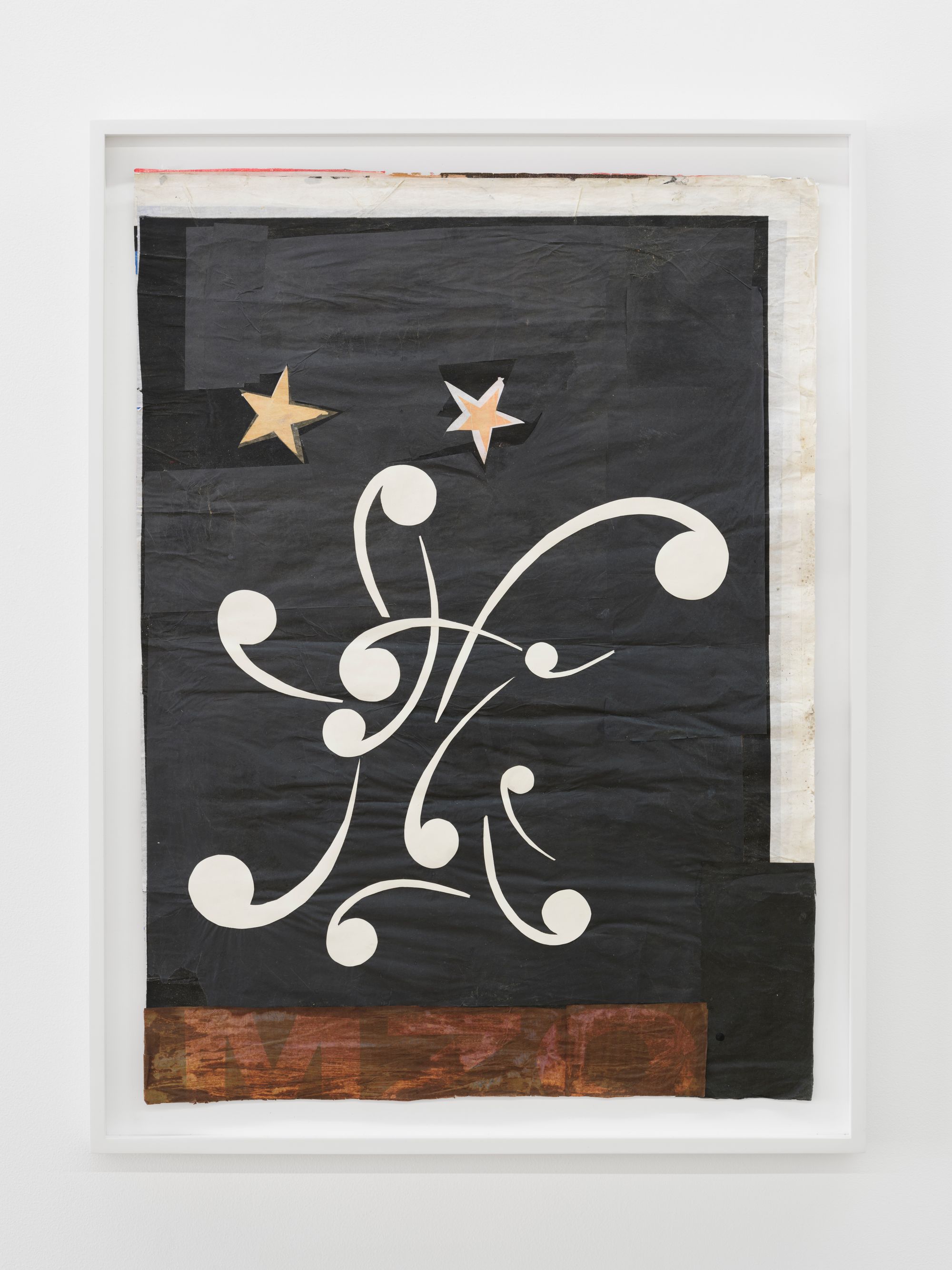

Lotte Andersen, Dancing Froglet, 2023, in Crowds and Crate Diggers. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

Was it a useful experience? How has it transitioned naturally to sculpture?

Totally. There’s also this element of journeying that comes with great social experiences and it was natural, then, that performance and sound and sculpture would emerge. When it comes to my work, I create very specifically through my own body. So I can measure things out with my height and my arms. I’m very autodidactic in that way. For instance, early last year I was invited alongside Alonso Leon-Velarde and Naima Karlsson to perform an anthem in the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. We worked with an 8-piece horn and percussion ensemble to arrange an anthem we wrote the previous year for a group show I did at David Kordansky Gallery. I was really keen to perform the work in the circular central atrium and interested in how the architecture would act like a speaker to amplify and multiply the sound.

Your use of music in your work is unique as well because you use sound as a textural and immersive material versus an independent product. What was your experience like creating sound installations for Crowds and Crate Diggers?

I am, first and foremost, moved by pop music. Growing up, my dad made jingles for a living. So there’s this idea in the back of my mind about what a hook means and [the structure] of a song. The power of sound is very haunting — you can’t shake sound. For most of us, the thing that we carry the most in our minds and memories is a [song], or a melody; echoic memory stored in the brain. With my most sound works, I’ve been [thinking] about fairy tales. That’s also the effect of living in Mexico and the magical realism that exists in this land. I worked with this type of [storytelling], in a nursery rhyme where I rewrote the lyrics to a very frightening rhyme [called] Ten Little Indians. I spent some time listening to songs and looking for the right source material. And in that case, a nursery rhyme was perfect, as they can carry the same weight as fables do. They don’t smack you in the face. It doesn’t say it’s literally teaching you anything. But it stays. And I think that that element — the hook, the lyrics — that can remain in the psyche. Most modern nursery rhymes have their roots in historical events like the Plague or Jim Crow.

Install view of Lotte Andersen’s Crowds and Crate Diggers at Helena Anrather. From left: Fools Rush In, 2023; Chaos has no morality II; Lullaby for expansion, 10 Ideologies, 2022. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

What’s your collaborative process like?

It’s very practical and harmonious. I wrote the lyrics to 10 Little Ideologies, and shared them with my sister Nancy [of the band Babeheaven] who performed and arranged the melody. Finally, it was recorded by my dad in his studio. There is this element of speed, of us being able to work very quickly, in whatever capacity. I have an interest in “family bands” like the Jackson Five, where people have been amongst each other for so long they have an innate sense of performance and improvisation when they play together. It’s been amazing to work with Naima [Karlsson] and Alonso [Leon-Velarde] as they also have this sense of musicality in their families too.

That experience of creating, especially within the family unit, is unique. A lot of people consider creating art to be a very solitary activity. And yet, these works have been a product of the intimate relationships in your life — I think that’s very impressive.

Thank you. I didn’t go to art school, so there are elements of me that just weren’t professionalized or streamlined. I’m not so separate from the work I make. It’s been me, whether it’s a puzzle, a sculpture, a party or a video like Dance Therapy. It’s always coming from a deep and personal place. Recently, I’ve been thinking more about working in a team after a little while of working a lot by myself. When I make collage, depending on the size, I’ll often be working alone, in a more painterly way within a solitary studio practice. It’s something that I have to really push myself to do, as I’ve come to art-making through groups and play, but somehow and someway it’s always collaborative. I don’t believe so much in these solitary, great artist figures. Even by inviting another artist in for a crit, breaks this…

I think there’s this narrativized figure of the lone male artist genius — the Donald Judd, or Carl Andre types — where they’re existing in their perfectly articulated universes that they alone created.

It’s interesting to me. I think about those types of artists a lot — I made a group of three sculptures in 2022, which were based on Walter de Maria’s Triangle, Circle, Square, and the writings of Donald Judd. But there’s a part of me that is inherently so British, so there’s a silliness or humor which sometimes interrupts the work, or an element of camp within how I approach it. I can never be those men. Maybe I could be as good as those men, but I will never be those men.

Photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

Lotte Andersen photographed by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

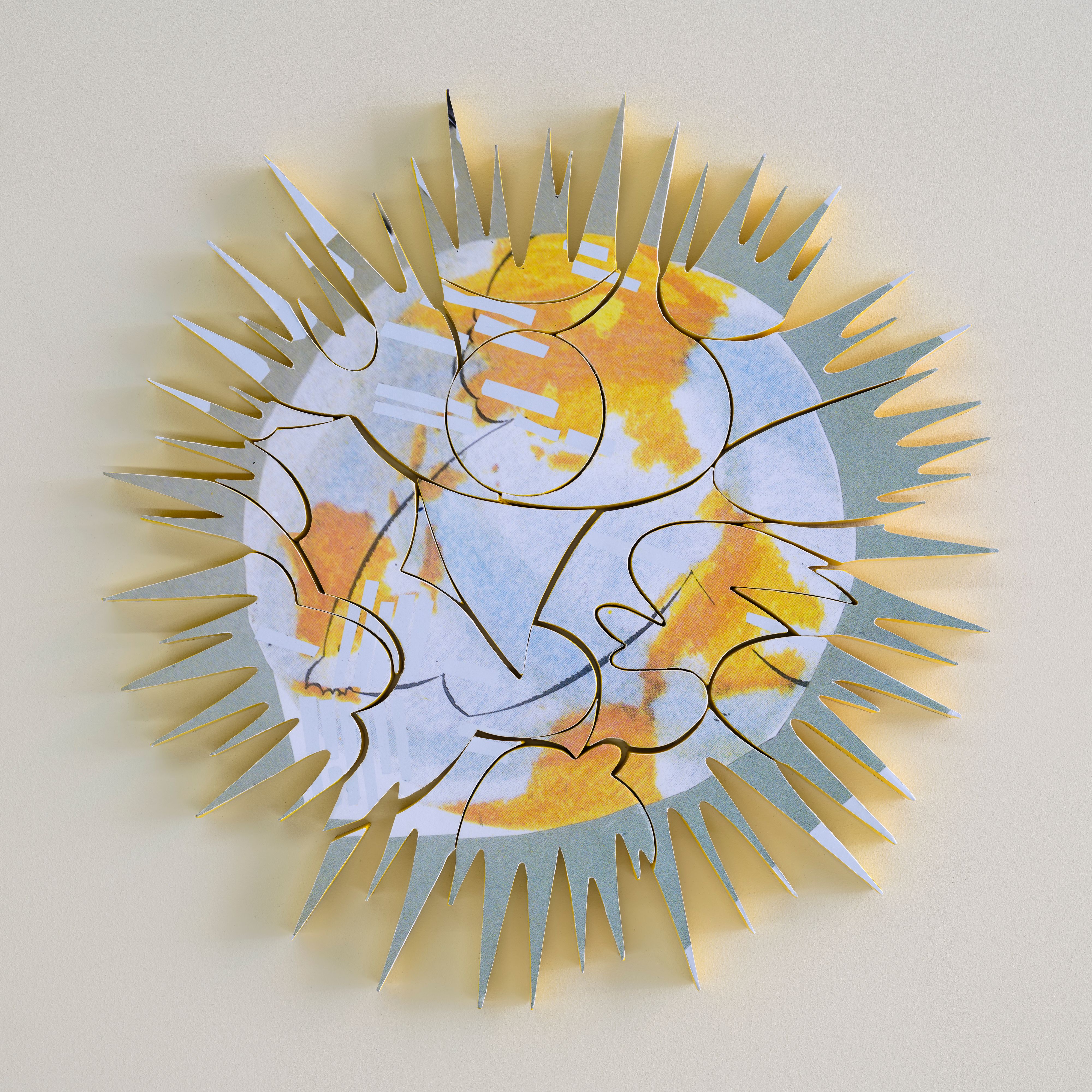

Lotte Andersen, Hexachords, 2023, in Crowds and Crate Diggers. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

Puzzles are a prominent motif in your work. They encourage participation, beckoning people to touch them or move them around. How’d you arrive at this repeating symbol?

When I started making the puzzle works, we were coming out of a global pandemic. I’d experienced it from the global south [living in Peru] and my whole brain had been shifted, yet I had developed a deeply social practice, making celebratory, participatory and performative work. I began to think about how to resolve those elements within health and safety guidelines. So I needed to start thinking about what if the bodies became objects, and what if the objects could still have this sense of movement? What if there was an incentive for the viewer to potentially place or move around these objects? Essentially, how can I still get engagement from the viewer and from the viewer’s body. The puzzle became a tool to unpack metaphors of conflict or family history, each piece symbolizing a different vignette or social circumstance. The symbols in the puzzles are very precise, for instance in the work Nancy noo, where an image of my sister is broken into shapes is reminiscent of pacifiers and rattles. I also like to think a lot about where I’m showing, and the different kinds of histories that exist in the space. In this way I can think about the scale of a sculpture and if it will actually get played with.

I’m curious how this past show fits into, or interrupts, the landscape of New York specifically.

I very intentionally decided to try to not interrupt the landscape of New York. I come from a very different art world, growing up in London in the 90s — I saw a very different landscape for the YBAs for instance. New York is so saturated already, I think a very arrogant person comes thinking they are going to wipe the slate clean. I knew I wanted to come with a very warm energy into the city. I hope that the show communicated that wish. It’s very optimistic, and yet there’s a huge amount of content and research, but it felt like everybody just needed a bit of space. I want to put on a show that’s like a breath, where you can see the wrinkle of time in these works. A melodic line running through that meanders and journeys. I was interested in a pause. This isn’t punching through something, I wanted things to flow, and I worked chronologically rather than controlling the space. The connective tissue between each piece often returns to this idea remembering and noticing hierarchies, and then putting some breathing space around them.

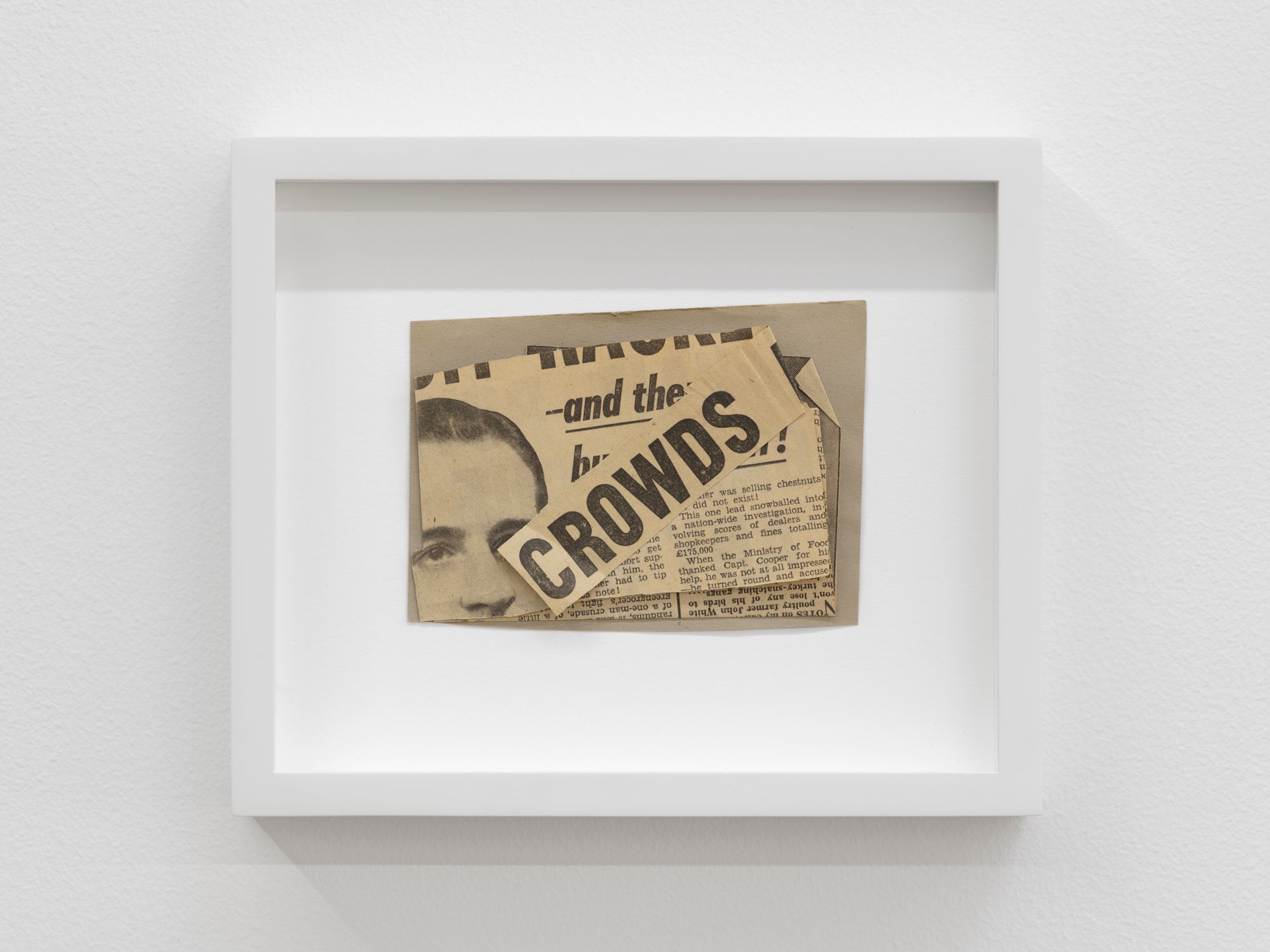

Lotte Andersen, Crowds, 2023, in Crowds and Crate Diggers. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

Installation view of Lotte Andersen’s Crowds and Crate Diggers at Helena Anrather. On the wall, from left: Quiet Froglet, 2023; After Arcimboldo, 2023. Below, from left: Fortuna, 2023; nancy noo, 2023; The Messenger, 2023. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

Definitely. And how has your work changed?

I feel like the way I use and insert language into the frame is much lighter than it was before. I have been learning to speak Spanish since moving abroad and I began to notice how communication is so much more than just the words you use. It’s often about everything else, tone, gesture, cadence and presence. My work was very wordy, and now it’s become much more efficient to think of the letters as gestures and symbols. There is a repeated use of what could be noticed as a comma, or musical note, or speech mark which appears in my puzzles and collages, I want the content to open up or to transgress into something generous. We’re in a moment where a combination of words can do such significant damage, and as a generation, it can feel like we are in a habit of throwing around words that we don’t fully understand. It feels vital that as artists, we find the power again in the symbolic quality of how we communicate, particularly when speaking across different cultures. I think that that’s where play can become a tool which is really important in softening and bringing levity. That said, I have been so happy to begin to include Spanish in my work… like the word “viento” [wind] which swirls up Fools Rush In, amid a throng of red musical notes. I learnt both French and Spanish by ear without formal lessons, so there’s a way I tend to hash up sentences quickly. I want the language visible in my work to carry on this sensibility, of being cobbled together to make for a very personal, visual vernacular.

Lotte Andersen, Songs in the Key of Life, 2023, in Crowds and Crate Diggers. Photo courtesy of the gallery and artist.

In the early stages of conceiving of a work, do you use prompts or mantras? Does your process feel organic, or intensely focused?

I’ll have a feeling, a sense. I wanted to make puzzles before speaking with Claudia Rankine’s curatorial group, The Racial Imaginary Institute, who organized [the show] All Opposing Players at Kordansky, and it happened to be based around ideas of nationalism. When I started to look into the idea, I found out that modern puzzles supposedly originate from John Spilsbury, a British cartographer hired by King George the III. The puzzles were called “dissected maps,” and used to teach royal children about world geography, which was just Europe and a bit of North America [laughs]. I’ll have these feelings or moments of intuition, and here it was very serendipitous to discover these histories.

It’s been informative being in Mexico and Peru, especially because of the artists who have lived here. There’s this shared cultural understanding of working with your unconscious, like Leonora Carrington haunted by ghosts. But let’s not forget she is being haunted by the European society she’d fled from and didn’t want to be a part of. With those kinds of surrealist women, there’s something there that I’ve always been very fascinated by.

Lotte Andersen photographed in front of a painting by Alonso-Leon Velarde. Portrait by Alberto Bustamante for PIN–UP.

How did you land at the title for the exhibition, Crowds and Crate Digging? Did you grow up in record stores?

Yes. My dad collects records. He’s got about 2,000. My grandparents are antique dealers, so it’s a hereditary hoarding problem for sure. I found the term crate digger, which refers to groups of anoraks who search vinyl in crates really attractive. This idea, has carried through practice, this idea of hunting for gear, or gathering things. I figured that that’s what I’d been doing for the last five years — traveling and sifting around, going into antique shops, libraries, markets. Thoughts as well as objects. There’s something extremely optimistic about being a crate digger because you just don’t really know what you’re [going to find]. There’s a meditation to it. I was also reading [lead singer of The Slits] Viv Albertine’s book Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, and I was thinking about how punk had formed. In some ways I see that spirit carried through the gibber collages works embedded within fragments of Chicha posters. I was really connecting back to where my practice first started, which was social. How can you be defined by the crowd that you surround yourself with, or the crowd that you exist in? Crowd is also an English word for “scene,” and scene-building. It felt very appropriate because the works are also very crowded. They’re packed. Materially, they’re thick. There's layers upon layers of posters and music and photos. And so there was this element of thinking about the historical context of that materiality, and what I was bringing into the room as well. My own baggage [Laughs].