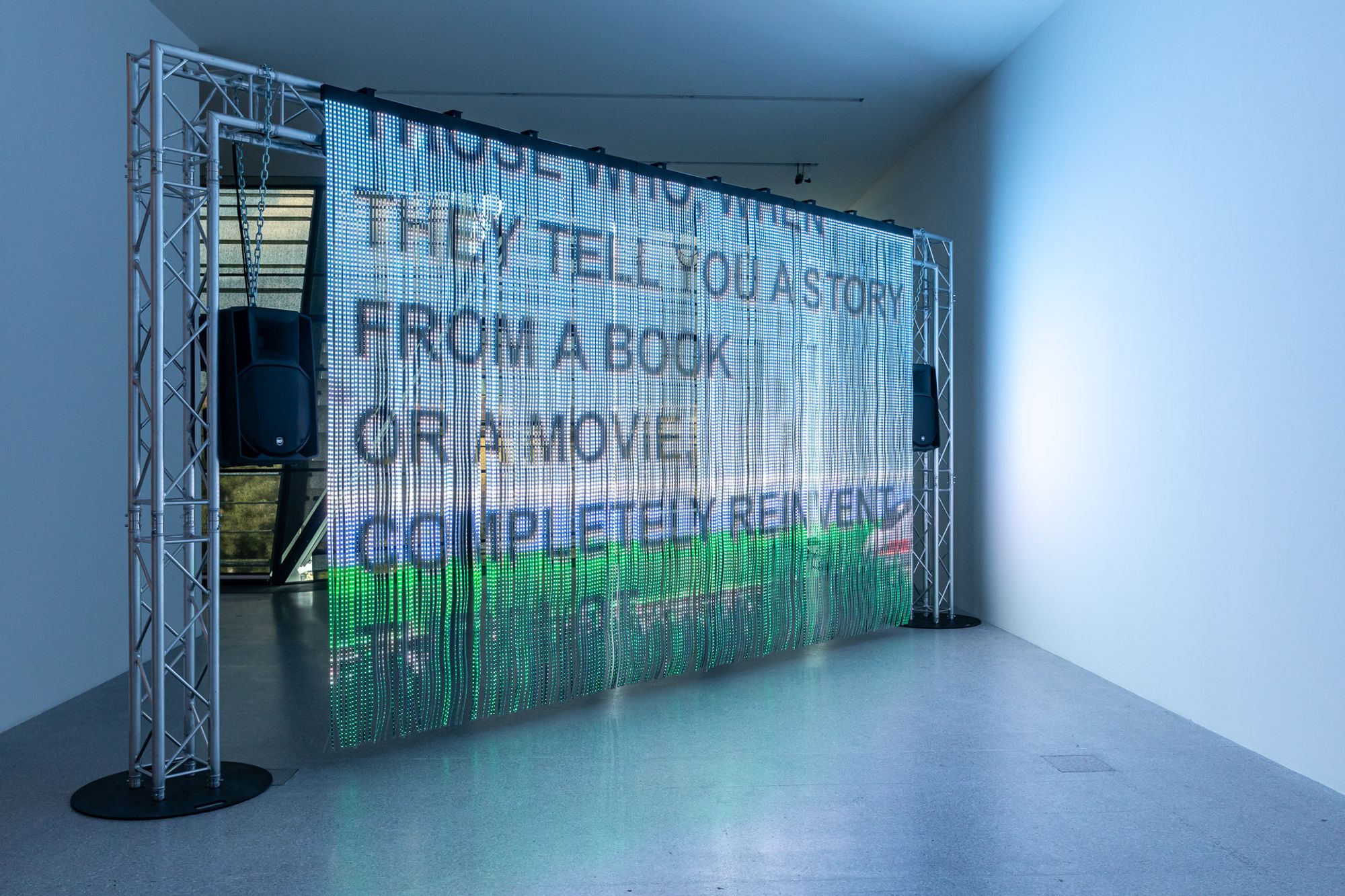

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia, 2019. Techno, 2021, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

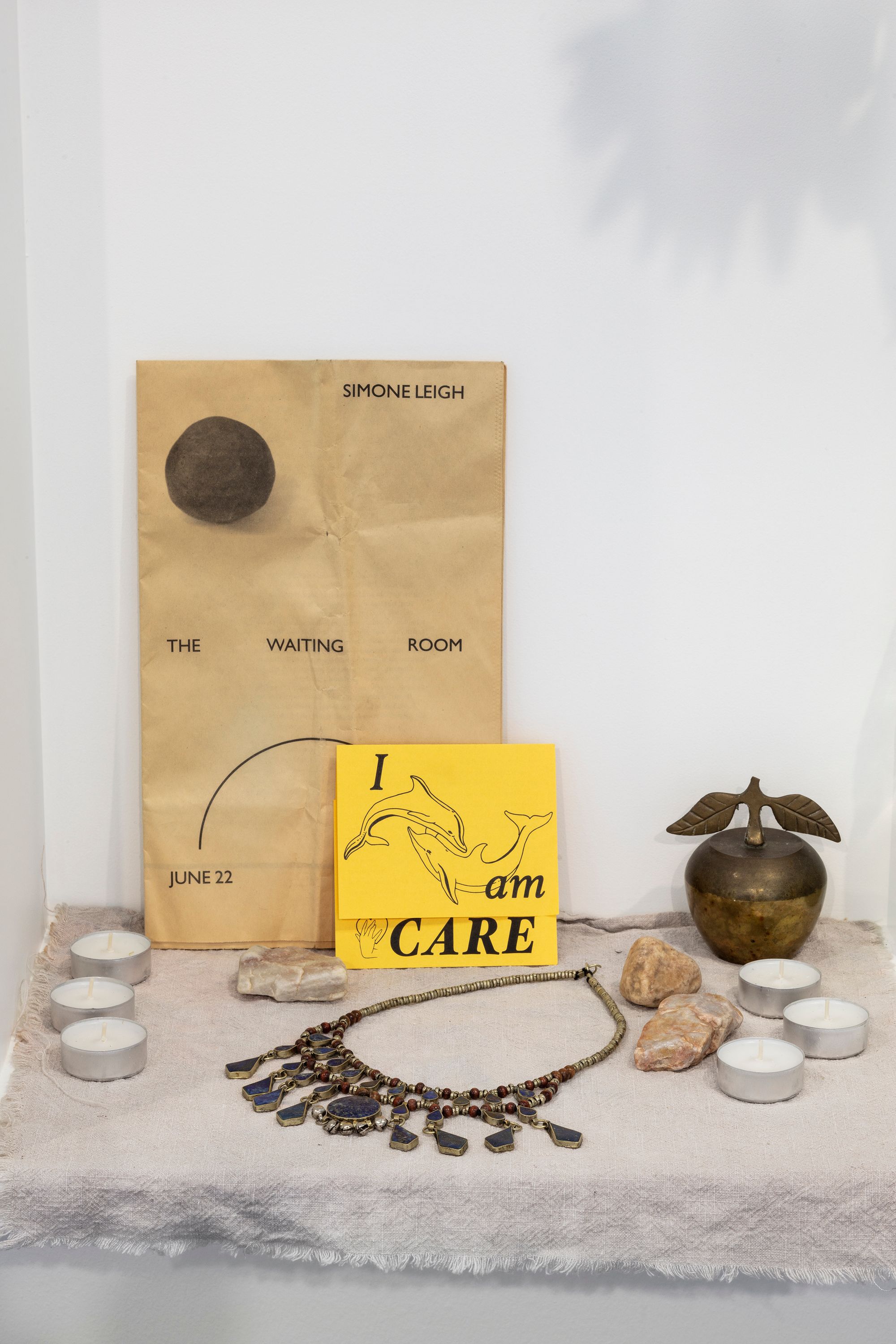

Front: Adelita Husni-Bey, Encounters On Pain, 2018-2021. Installation with medical paper, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the Artist and Laveronica Gallery. Back: Adelita Husni-Bey, On Necessary Work, 2021. Film installation, HD video, zoom and mobile phone, 32' 44". Courtesy of the Artist and Laveronica Gallery. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

If we’re to take some art world discourse at face-value, institutions need to be revived, museums are in flux, and the canon is obsolete, at least as we know it. These ideas circulate not just in the close-knit circles of New York, London and other metropolitan art cities — they’re taking hold just past the foothills of the Alps, too. Last fall, just after the general election in Italy, the exhibition Kingdom of the Ill opened at Museion, Bolzano’s contemporary art institute, which set forth a bold vision for the future of museums during a fraught political moment: the newly elected prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, and her party, the Brothers of Italy, hope to reshape the cultural sector to its advantage. The education minister stated that schools promote wokeness instead of preparing children for a competitive job market. The new government vowed to criminalize “cancel culture and iconoclasm” by drawing on what it calls Christian values, which many fear will exclude queer people, migrants, and other groups: an attempt at reterritorialization against a globalized world in motion.

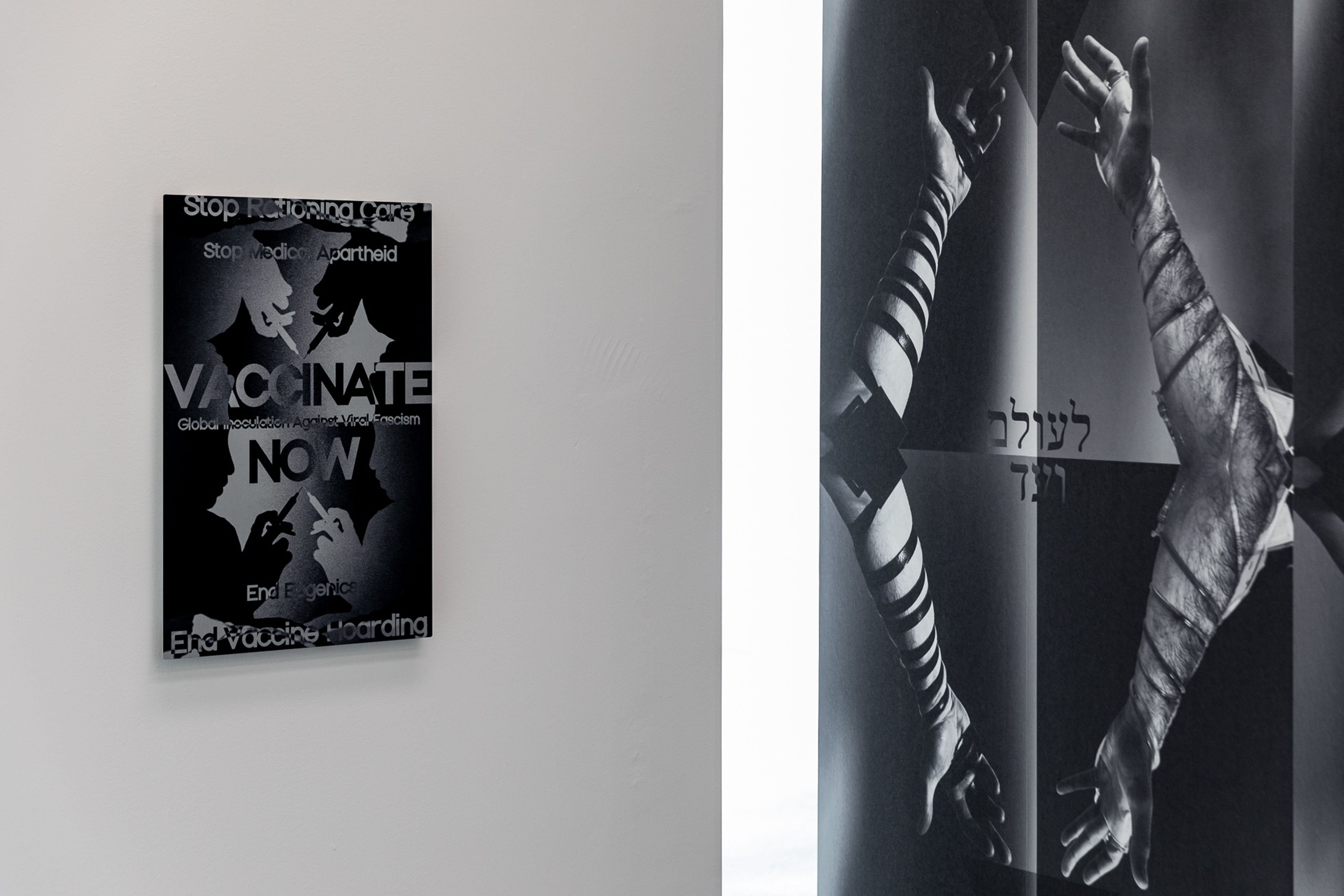

Museion Kingdom of the Ill exhibition header. Art work: Brothers Sick (Ezra and Noah Benus). Graphic design: StudioMUT.

The new show at Museion, perhaps unintentionally, feels like a counterprogram to Italy’s right-wing government. With more than twenty artists in the exhibition, Kingdom of the Ill has placed concerns like care and healing at its center. The exhibition is the second part of a series: Techno Humanities. The first, ominously named Techno, was on view a year ago and assembled works that mostly had no obvious relation to techno as a subculture, but rather framed it as a cultural paradigm. The project avoided the pitfalls of nostalgia for bygone eras of electronic music, and abstained from a romanticization of club culture while incorporating communities from the surrounding mountains who throw parties and make electronic music.

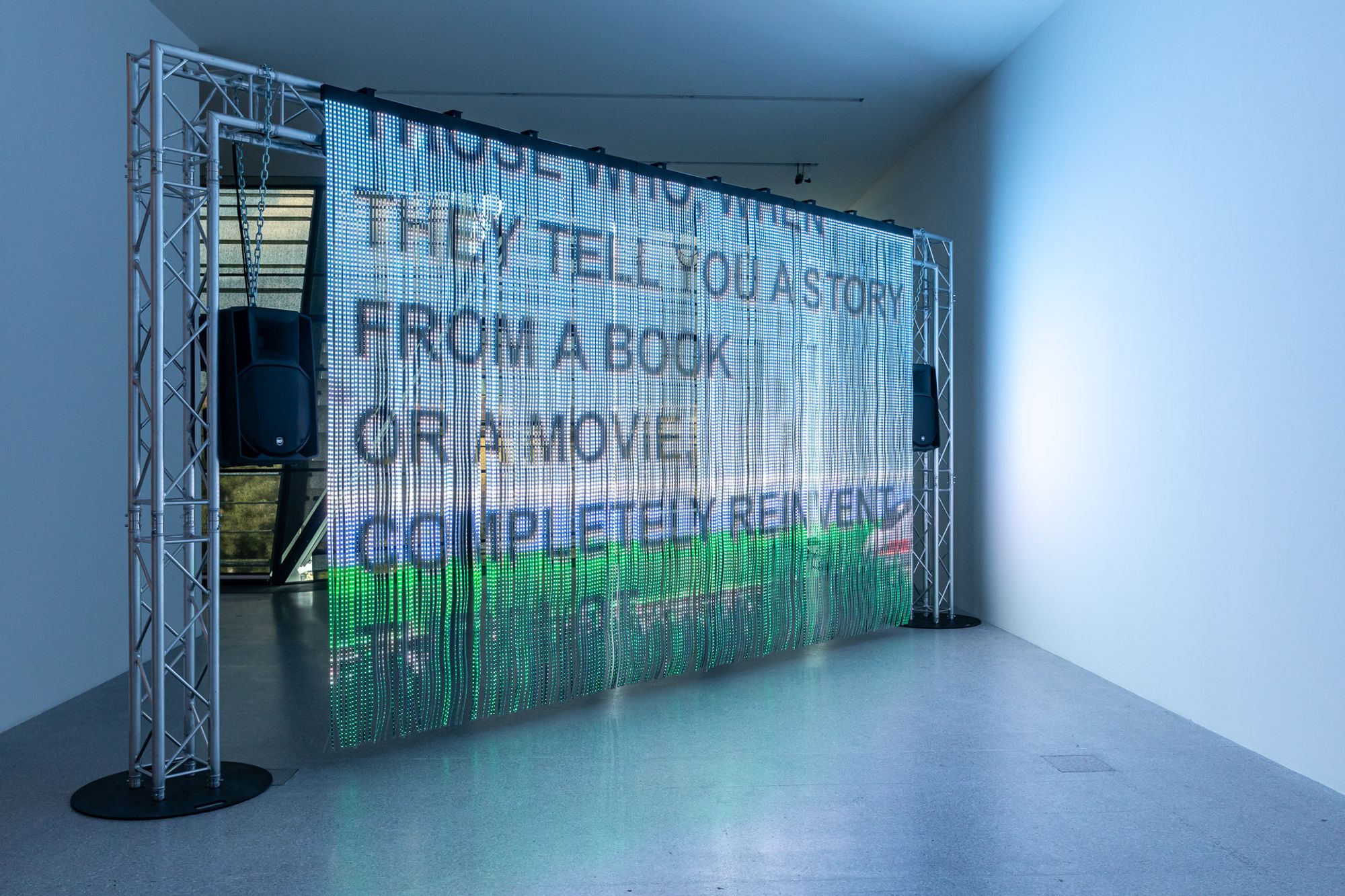

Works from the past five years occupy the four levels of Museion, beginning with a portal-like entrance on the ground floor. One of the walls that divides the space is covered in vinyl wallpaper, a work by New York-based siblings Noah and Ezra Benus, aka Brothers Sick. It shows an infinitely repeated pattern of four forearms reaching towards a black triangle. Around two of them, intravenous tubes coil, and around the two others, a tefillin. The Hebrew words “for the world eternal” are written above and below; the inverted triangle is a reference to the symbols used to classify prisoners of concentration camps. The Hebrew phrase, which comes from a morning prayer, can be read as a statement of resilience. The work voices hope for a future no longer tied up in conventional ways of understanding chronic illness, which sets the tone for this show.

Riccardo Benassi, Morestalgia, 2019. Techno, 2021, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Nicolò Degiorgis, Rave Grounds, 2015-2021. Courtesy of the Artist. Techno, 2021, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Left: Brothers Sick, Pareidolia (Vaccinate Now), 2021. Dye-sublimation print on aluminum, 40.64 x 60.96 cm. Courtesy of the Artists. Right: Brothers Sick, דעו םלועל/for the world eternal (detail), 2022. Wall vinyl, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the Artists. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Kingdom of the Ill was guest-curated by Pavel Pyś and his partner Sara Cluggish. Pyś — curator of visual arts at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis — and Cluggish, who is curator and director of the Perlman Teaching Museum at Carleton College, started thinking about this exhibition before COVID-19. It is as if they anticipated the global emergency that would lead the world to reconsider the very tenets of health, safety, and vulnerability. "Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick," Susan Sontag wrote in her 1978 essay “Illness as Metaphor.” The strikethrough in the show’s title — easier to write than to pronounce, says Pyś — is not taken from Sontag’s text. However, it echoes a favorite strategy of poststructuralist philosophers: cross out terms that are inadequate but necessary. Perhaps the typographic quirk indicates the dissolution of the kingdom of the sick, or illness as a spectrum. At the press tour, Pyś speaks about a continuum in which we can never clearly identify as healthy or ill. At the preview, a fellow journalist is not happy with this. The very visceral state of sickness is not a choice, she whispers, it is real, and the real is difficult to argue with.

P. Staff, Acid Rain for Museion, 2022. Steel drums, galvanized steel pipes and fixtures, mild steel tanks, fibreglass, acid, various materials. Variable dimensions. Courtesy of the Artist. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Diogo Passarinho Studio, who were responsible for the exhibition architecture, touched the building’s four above-ground levels only slightly, but the impact on the space is significant. P. Staff’s installation Acid Rain for Museion, for instance, is lodged in a corridor between two walls, one of which is a partition installed by Passarinho and Reynolds. The artist’s work itself pretends to be infrastructure: thin metal pipes, suspended from the ceiling, drip an acid solution into steel barrels, slowly making them rust, while the space is bathed in sickly yellow light. On the other side, there are drawings and photographs by Nan Goldin, alongside paraphernalia from protests of the group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now — P.A.I.N. — which Goldin founded in 2017. Banners read “200 Dead Each Day,” or “Shame on Sackler,” the family that owns the company producing and promoting the highly addictive opioid Oxycontin. The Sacklers are also patrons of the arts, and their name is written on museum walls across the world. Since its conception, P.A.I.N.’s institutional critique has prompted museums to drop the family’s name from their galleries. The most impressive piece by Goldin, however, is Memory Lost (2020). Though modestly billed as a slideshow, it’s really a film about addiction and memory, and a document of the friends the artist lost to the drug.

The topmost floor is a large, open-plan space. Ambient music can be heard from Barbara Gamper’s work, which includes a guided meditation. Artworks are strewn about the ample terrazzo floor, and its openness invites a more intimate interaction with the pieces. Some are to be laid on, others to be listened to. Many, including the installation by Berlin-based poet and artist Lauryn Youden, encourage quiet contemplation: a shelf full of books, herbs, pills, candles, and flowers, are the artist’s personal possessions connected to non-Western traditional healing practices. “It is a way of getting to know a person without seeing them,” says Pyś. Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Phillip Andrew Lewis’s installation imagines a future of mourning, in which the DNA of deceased relatives is engineered into psychoactive plants. The compound is sectioned off by four large panels of foil. The space is soothing, and the windows offer a view on lush green mountainsides. The works deal with care, death, and healing, but the term ‘self-care’ is conspicuously absent from the exhibition. Instead, it speaks about radical care and community and its implications of solidarity across different activist groups.

Barbara Gamper, Sense(s) of coherence, 2022. Somatic audio meditation, digital audio, ca. 45'. Courtesy of the Artist. Barbara Gamper, The Big Blue (detail), 2014-2015. Hand-tufted tapestry, 120 x 170 cm. Courtesy of Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano-Alto Adige / Autonome Provinz Bozen-Südtirol / Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Lauryn Youden, From the Great Above she opened her ear to the Great Below (detail), 2020. Various materials, 378 x 32 x 100 cm. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Timo Ohler.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Phillip Andrew Lewis, Spirit Molecule (detail), 2022. Psychoactive plants, greenhouse installation, single-channel film, 7' 29". Courtesy of the Artists & Fridman Gallery. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.

Illness and structures including the economy, nation, and society overlap. These are the contexts Johanna Hedva thinks about. The artist has a video in the show — Untitled (Somebody Cheating Me) — where they pair footage of their grandmother with the cold and impersonally greedy tone of her medical bills. Hedva watches from the perspective of the caretaker, while the older woman, who suffers from Alzheimer’s, recites the bureaucratic prose, stumbling over words and hesitating. Hedva also wrote their seminal essay “Sick Woman Theory” in 2016 while bed-bound by chronic illness, unable to attend the Black Lives Matter protests a block away in their city of Los Angeles in the wake of Ferguson. At that time, Hedva addressed the political implications of disability and chronic illness, which became magnified in 2020 as the mainstreaming of the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests dovetailed with the pandemic. In her essay, Hevda critiqued Hannah Arendt’s canonized definition of the political, for its suggestion that the publicly absent are, by implication, politically absent. “Sick Woman Theory is an insistence that most modes of political protest are internalized, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible,” writes Hedva. The personal is political, which is a pervasive concern of this exhibition.

Nan Goldin, Memory Lost, 2019-2021. Digital slideshow; 24 min. 16 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Copyright: Nan Goldin.

Over the last twenty years, museums have been plummeting into an identity crisis, claims Bart van der Heide, the outgoing director of Museion, who initiated the project. The critic Ben Davis observes something similar in his recent book, Art in the After-Culture, and attributes it to two tendencies. One is the touring blockbuster show, which reaffirms the museum’s role as gatekeeper while also appealing to large audiences. Secondly, museums turn into attractions, as culture is democratized to the point of extinction. Van der Heide believes that, with this backdrop, institutions are losing their relevance. “A museum can be a showcase and a place for blockbuster exhibitions,” he told me over a late espresso after the preview day. “But in my understanding, it is much more. It is like a body in itself.”

The ambitious project Kingdom of the Ill is calling for a politicization of the vulnerable body while museums are grappling for relevance, and not just as they face the onslaught of the far right in Europe. Museums’ discursive power is decentered by critical movements: art institutions are increasingly under pressure to be socially relevant and to reform the way they work. Techno Humanities, wrote van der Heide in an email to me a few days later, should be a commitment for all institutions. The series has been conceived as a strategy to step out of temporary shows, and incorporate larger lines of inquiry in collaboration with research teams — “not in terms of answers, but in terms of questions,” says van der Heide. “The museum does not set a standard,” he replied when asked how he envisions the museum of the future. “It proposes models for a society we want to create, and that stands for values of non-violence, cooperation, solidarity, and support of the creative sector.”

Top: P.A.I.N., Louvre Action, 2019. Bottom left: Oxy Dollar/Bankruptcy Court Action, 2019. Two-sided, two-color risograph print, 15.5 x 6.5 cm each. Courtesy of P.A.I.N. Bottom center: Original Met pamphlet (March 2018) annotated for edits, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Found material, 21.5 x 14 cm. Courtesy of P.A.I.N. Bottom right: P.A.I.N., Met pamphlet reproduction, 2018. Inkjet print on paper, 21.5 x 14 cm. Courtesy of P.A.I.N. Kingdom of the Ill, 2022, exhibition view, MUSEION Museum of modern and contemporary Art Bolzano Bozen. Credit: Lineematiche/Luca Guadagnini.