COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY’S KELLIE JONES ON TEACHING AND UNCOVERING HIDDEN HISTORIES

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

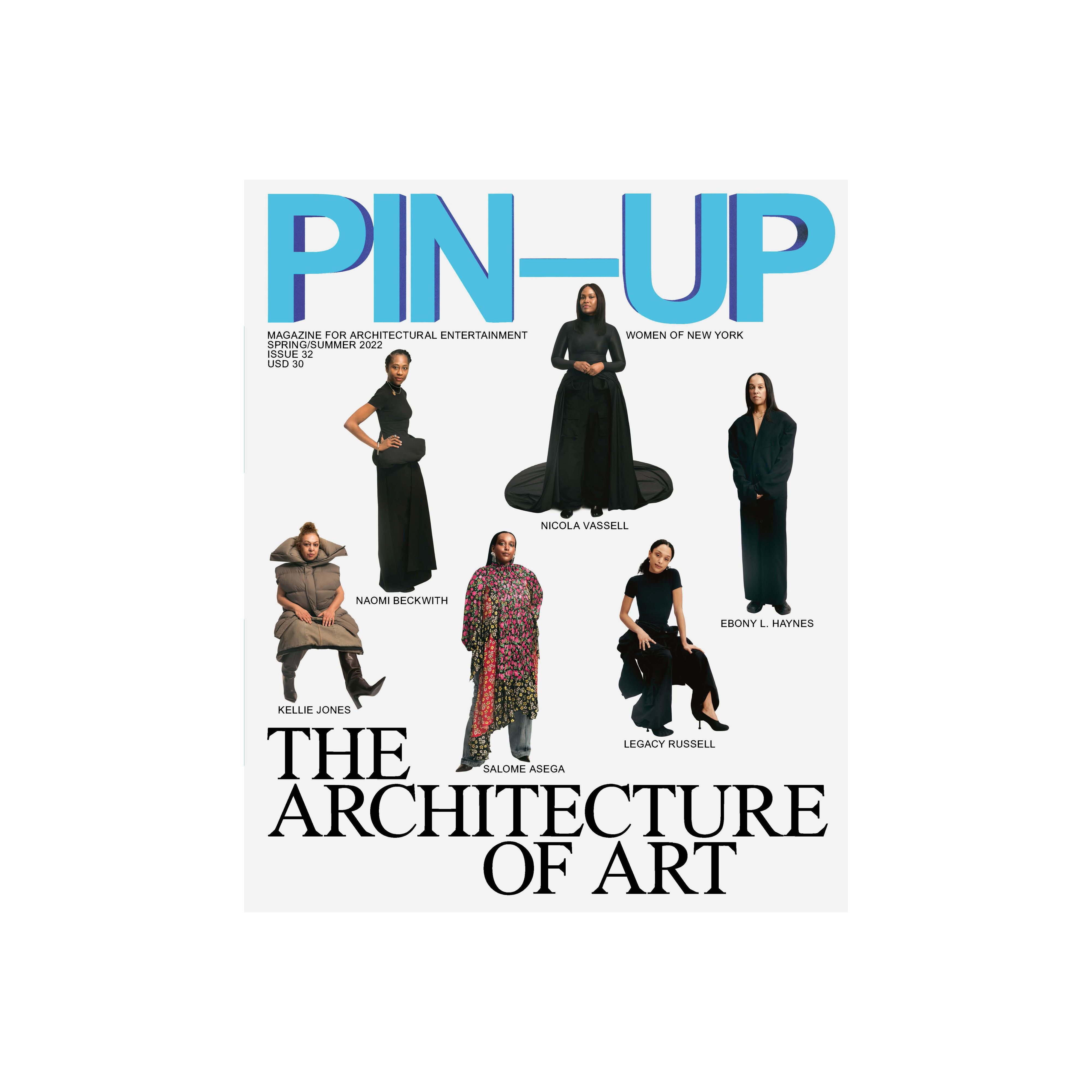

Kellie Jones photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

Art historian and curator Kellie Jones understands the stories you can uncover through excavation. Chair of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, where she is also the Hans Hofmann Professor of Modern Art, the MacArthur Fellow has spent three decades developing a research and curatorial practice that focuses on the art of the African diaspora. Emblematic of her concerns, her 2017 book South of Pico ties together the work of Los Angeles artists like Betye Saar, Charles White, and Noah Purifoy with the history of Black migration in the United States, urban renewal in L.A., and arts activism. In 2002, with Thelma Golden, Jones surveyed Lorna Simpson’s photographs and films and their relationship to self-portraiture at the Studio Museum in Harlem, while in 2005 she co-curated a Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, featuring works never seen before in the U.S. The following year, in another Studio Museum exhibition, she brought together artists like Howardena Pindell and Daniel LaRue Johnson to prove that the supposedly ironclad link between Black artists and figurative work leaves out a whole history of abstraction and Expressionism. In addition to bringing such stories to light, Jones is teaching a new generation of students to take this political process of worldbuilding forward.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: Who is Kellie Jones?

Kellie Jones: Kellie Jones is a girl who had poets as parents, so I blame them for all my eccentricity and creativity. I grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and blame all the artists I knew for all the things I learned. I went to an urban high school and am a big believer in public education, because it allowed the people of my generation to thrive. It’s now called Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. When I went there, it was very much populated by people of color and it was on the City College campus. There were people who went there who you probably know: Whitfield Lovell, Fred Wilson, Marcus Miller, Kurtis Blow, Billy Dee Williams, all successful artists and musicians… And I’ve also known Hilton Als since high school.

How did you and Hilton meet?

Hilton went to Performing Arts, which is now a part of LaGuardia’s programming, and we met through a mutual friend. Before, the music and art schools were uptown, and performing arts was in midtown. This is what you get with New York public high schools, so it’s why I’m a firm believer. He once wrote about my mom, Hettie Jones, and his high school days, and revealed what that urban high-school experience did for him.

What was your college experience like?

I went to Amherst College in Massachusetts. It had just become coed when I started going there — I was in the second class of women who were freshman. I wanted to be a diplomat, because I didn’t think I’d be an artist or work in the arts, but then I started interviewing people like [painters] Jack Whitten and Norman Lewis as an independent-study course, and I realized I could write and be a curator. I did an interdisciplinary degree between art history, Spanish, and Black studies. I’ve been doing the same thing ever since. Today, engaging Latinx studies is very hot, but that’s just how we grew up.

What did it mean to you in the context of that community?

I knew artists growing up, so I always talk about it, and people always say, “Does that mean I can’t be an art historian because I didn’t know them growing up?” [Laughs.] And I say, “No. I knew them, and when I read history books, there were no Black people, no people of color, and everyone was mostly ancient. I knew they were wrong because they didn’t cover the people that I knew existed outside of those history books.” I didn’t want to be an artist because I didn’t want to be broke. Certain Black artists had their moment in the 1960s and 70s, and then it was over. It’s lost on me when people outside the community claim to have not known about these artists, while the Studio Museum, Just Above Midtown, Linda Goode Bryant’s art gallery and self-described laboratory, and other organizations supported them. You can find article after article about these artists in the mainstream press, and yet they apply that same narrative of them being undiscovered.

When did you first encounter the Studio Museum in Harlem?

Before I graduated from college, I interned at Studio. After I graduated, I worked there, from 1980 to 1983. They had an internship program that they still have now where you work in every department. I was hired as the assistant curator and managed the Harlem State Office Building collection, as it was then called. After that, I had an internship at the National Endowment of the Arts, at Expansion Art, then I came back to New York to work for a developer/architect who wanted to build a museum for his collection, but it never happened so he gave his collection to MoMA. That’s where I encountered [writers and curators] Robert Storr and Joan Simon who had left Art in America to work there. Then I went to the Jamaica Arts Center in Queens.

Which is where you encountered Thelma Golden.

Yes, she was working at the Whitney Museum. I was getting ready to do the São Paulo Biennial, so while I was working on that show she took over the programming at the Arts Center, but I never ended up going back. I decided to go to graduate school instead.

What is your relationship to architecture and space-making? Your book South of Pico, which surveys Black artists in Los Angeles, seems like a kind of anthropological mapping of the city.

It was an excavation in some ways. I’m still obsessed with geographies and genealogies and uncovering these hidden histories, focusing on Black migration and how people try to find space for themselves, their lives, and the things they care about. While I was curating in New York, I met a lot of people from out West like David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Charles Abramson, and others who came in and out. I interviewed David in 1986, and he name-dropped all these artists I’d never heard of because they were on the West Coast.

What is art about for you?

It’s about a certain kind of freedom being made by a wide array of people. Art as a career move wasn’t a reality back when I was first engaging with it as a field. My sister and I laugh all the time at how many shows used to name-check Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Hilton Als, and other Black artists, because back then it wasn’t as much of a thing.

Did anyone help or guide you in your career?

When I was 30, I decided to go to grad school. I quit my job nine months before so I didn’t have a job to go back to. [Curator and art historian] Lowery Stokes Sims gave me all her outside speaking engagements throughout the year, which is how I survived those nine months. Thelma [Golden] and I talked about her in the conversation we have in the Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum catalogue, which is mostly about the Studio Museum’s history, but in the end we devolve into the fact that we’re a part of this long history. Thelma’s the longest-serving director of the institution, and it was when the museum started having women directors generally that the place really came to life. Thelma and I talk about how we only really knew Lowery Stokes at the time, and [artist, photographer, and curator] Deborah Willis.

How did you end up teaching?

I never set out to teach. I thought I’d go back to working at museums once I finished my dissertation, but then I ended up with a teaching gig at Yale. What I like about teaching is how you get to affect people in a different way. The museum affects people on one level, but being in the context of the classroom in conversation is a different thing entirely. When I curated Basquiat at the Brooklyn Museum in 2005 and Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 at The Hammer in 2011, there were people lining up around the block. It’s gratifying to see that something you were passionate about reached so many people. With teaching, I constantly joke that I’m not going to do this forever, but I’m always trying to create more opportunities for others in this field so we can move these histories forward.

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.