Shooting from the Heart, 1980. Tin plate, rods, spring, and gears. Photo by Robert Frank.

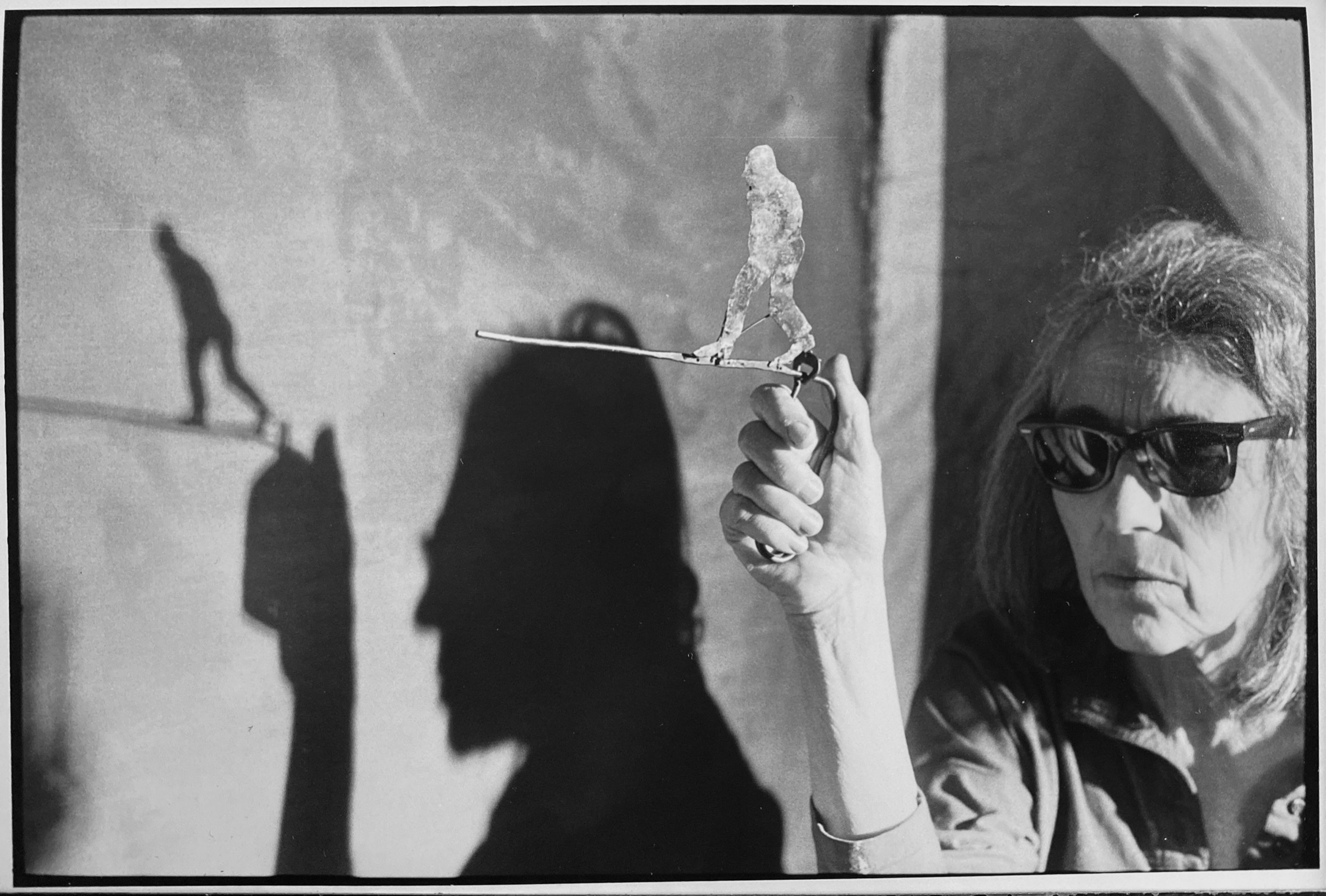

June Leaf holding her sculpture Woman Walking (1978). Photo by Brian Graham.

For over seven decades, Chicago-born artist June Leaf has captured the body in its many forms. In her paintings, drawings, and handmade kinetic sculptures, wide-eyed women let air out of balloons (The Salon, 1965), while a couple waits in line for the carousel at Coney Island (Coney Island, 1968) — the man smiles, the woman faces away. With Vermeer Box (1966), Leaf “made a woman in mirrors” because she couldn’t get the extra dimension she needed through paint, while other sculptures borrow the mechanics of egg beaters for their moving parts. Leaf, who splits her time between studios in New York and Mabou, Nova Scotia, where she has a foundry, is also the widow of Robert Frank, the Swiss photographer and filmmaker. Born in 1929, she did a three-month stint at the New Bauhaus in Chicago (now the Institute of Design) before moving to Paris in 1948, where she returned for a longer period of time in 1958. In 1968, she turned the Allan Frumkin Gallery into a carnival with marionettes and carousel horses for her first solo show in New York. Her practice took on an increasingly cyborgian bent in the 1970s, following the establishment of her studio in Mabou, culminating in a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 1978. Her prolific output continued apace over the next few decades, from her nimble drawings to paintings on curved tin, and small sculptures that move with the toggle of a sewing treadle handmade from wire, copper, and thread. In 2016, Leaf’s works were shown in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art (June Leaf: Thought is Infinite) and, more recently, at Tribeca’s Ortuzar Projects (June Leaf, November/December 2022). Leaf has described her relationship with the characters that inhabit her works, particularly her mid-50s figurative paintings, as one of obsession, release, and liberation, a process that may take a decade to work itself out. For PIN–UP, the visionary nonagenarian talks Hans Ulrich Obrist through her artistic trajectory since childhood, punctuated by preoccupations with high-heeled shoes, love, the human hand, and feet.

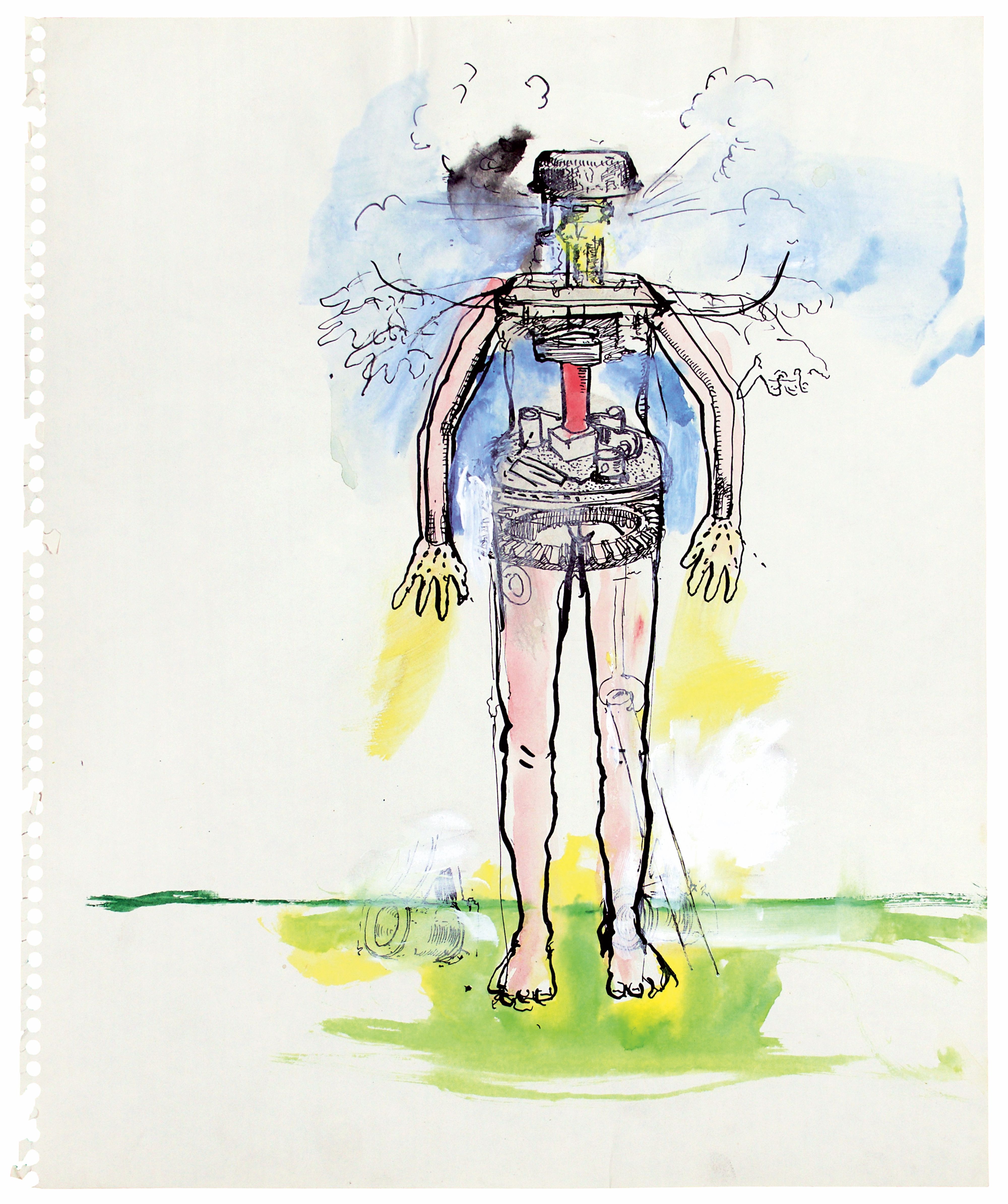

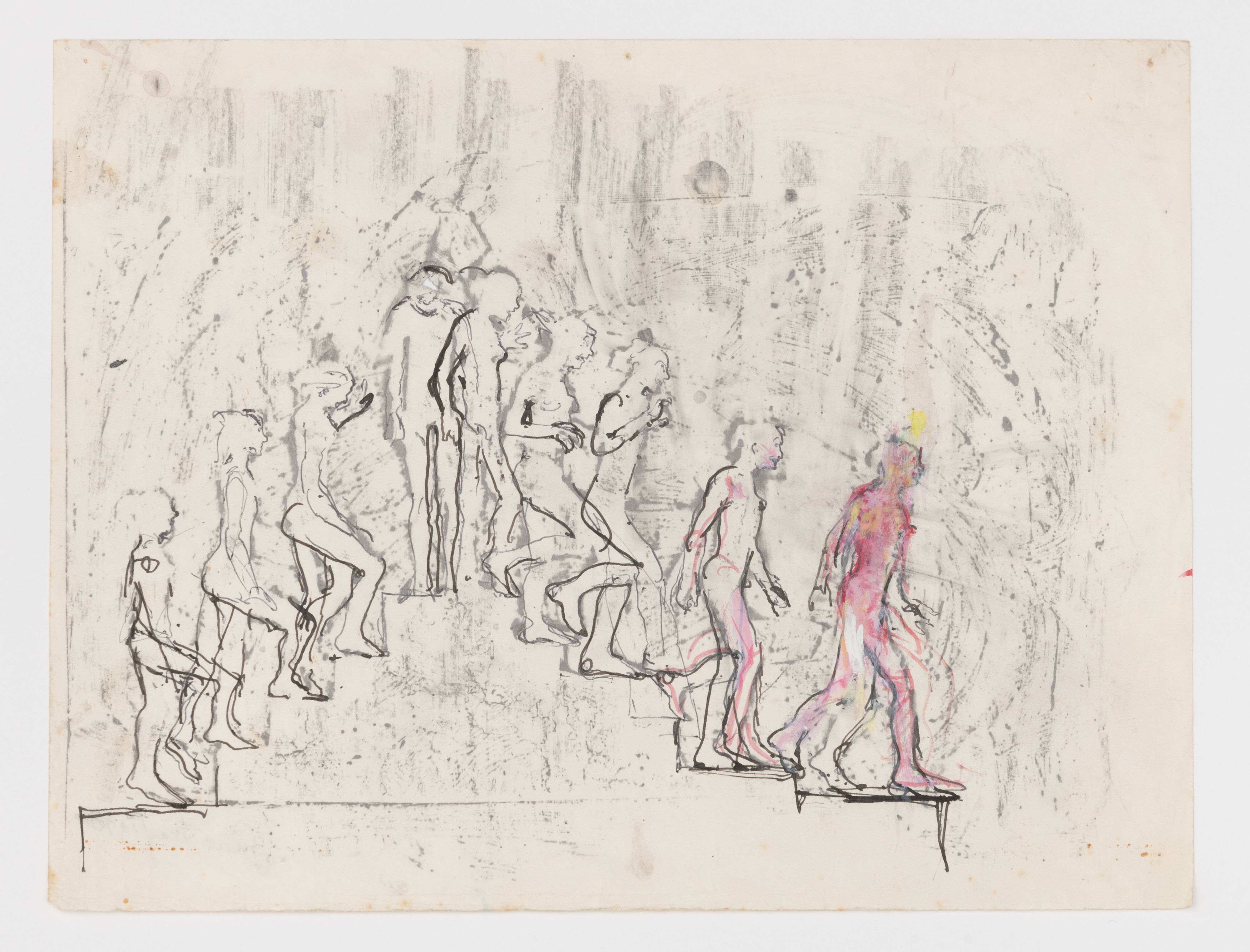

Study for Woman Monument, 1975. Pen and ink, and acrylic on paper. Photo by Alice Attie.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did you come to art?

June Leaf: It began when I recognized how I needed to make things with my hands. My mother was sitting at a table working on her sewing, and I was underneath it. I came out from under the table and — I know I was young because I remember seeing my hands — I took a pencil, and said to her, “Draw me a high-heeled shoe.” And she didn’t. I said to myself, she’s not interested. And I asked her again, “Draw me a high-heeled shoe.” She took the pencil and she made a drawing. And I looked at it and thought, “No, no, no. The toe goes down.” And then I thought, “She’s of no help to me. In fact, she might be a foe.” That was a very important day in my life, because I thought, “Well, I can never tell her what I’m going to do because she wouldn’t let me.” So I hid my destiny from her in a way, but that’s the day I decided what I would do.

I asked you what your secret was before, and you referred to your hands.

I do have a secret. It’s because I have happy hands. But at my age, when your life is coming to an end, you realize it’s very short. There are only about a dozen peaks in life.

Shooting from the Heart, 1980. Tin plate, rods, spring, and gears. Photo by Robert Frank.

Two Women on a Jack, 2001. Metal, tin, wire, wood and ratcheting jack components. Photo courtesy Ortuzar Projects.

I often ask artists about their epiphanies, about these peaks. And you’ve just told us one. Can you share another?

The next one was when I was in third grade, about eight years old. And I was much smarter then than I am now. The teacher would put the students who had already finished their work at the back of the class because they were ahead. I had to spend a lot of time by myself at the back of the class. That’s when I think I started to draw. I made a drawing of Joseph and his brothers because I thought that was the most heartbreaking story: the brother attempting to kill him, faking his death, and then he becomes a pharaoh. And he’s seeing them as pharaoh and he recognizes them and they don’t recognize him. I made a drawing of that meeting.

Do any others come to mind?

The search for Robert. Well, I didn’t know his name was Robert. When I was maybe six, seven, I was taking a walk in the woods at camp, and thought I saw a blond boy leaping in the distance. I thought, “I love him. That’s him.” I ran back and told the campers I loved him, and they laughed at me, but I didn’t even notice that they were laughing. Throughout my life, I would see indications of him having been there. I remember I went to a playroom and I saw a boy had left a drawing of a castle, brick by brick, which I was very impressed with. “He was here,” I thought, “and he’s an artist.” And throughout my life, I’d meet a man and something in me would say, “No.” Sometimes “Maybe,” then “No.” And then when I saw Robert for the first time at the end of the 60s, I was 36 years old. I saw him come into the room and I said, “Oh, there he is.” I looked at his shoes — no socks, raggedy cuffs, sloppy, arrogant. I saw everything. More arrogant than I thought he would be. I knew he was married. I thought it was good, because he’s a very difficult man. And then he followed me around the room. And I thought, “Also bad, he’s married.” [Laughs.] And that’s my story about Robert. I don’t think that happens very much. Even telling this story, it makes me want to believe that I don’t believe in predestination, and things like that. But at the same time, when I tell this story, it’s obvious that it had almost been written before me, and I was only following it.

June Leaf photographed working near the beach. Photography by Brian Graham.

But this has also happened with your work before as well. The idea of bringing Vermeer up to date [Vermeer Box] was a very important moment. So I was curious about making that decision in the mid 60s, because it’s one of your first sculptures.

That’s when I started sculpture. It was the woman and the gentleman and the table and the window and the tiles along the ground, and a picture on the wall [Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine, c. 1660]. I tried to paint the woman first, but I couldn’t paint her. I had to make dimensions that I couldn’t paint. That’s when I made my first sculpture — I made the woman out of mirrors, piece by piece. And I made the tabletop like a puzzle. I used comic strips to glue on the paper. And then I even made a hinge. It opened up what sculpture could do for me — it could go into another dimension. I’m an absolute mess of a sculptor. I go against every rule possible. I try to bend the materials, which I can’t do with painting.

As well as Vermeer, you also said that Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper was another revelation.

Because that’s the best painting that was ever made. Everybody thinks the same thing. Every house of someone who is not interested in art has a picture of The Last Supper. You can’t explain that. It’s always there. It’s the only painting that has changed the world, or moved people. And why? You can’t answer that.

Young Woman Going Up and Down the Stairs, 1978. Courtesy of Ortuzar Projects.

I also wanted to ask you about mime artist Angna Enters, because I read that she was a great inspiration to you.

I saw her when I was 16. I was in high school in Tucson, Arizona, for my health — my family sent me to a dry place for the winter because of my asthma. And for some reason there was a performance by this woman who was there. She must have been about 40 at the time. Her name was Angna Enters. She danced and made drawings on the stage. And I looked and I thought, “Oh, that’s what I’m going to do with my life.”

And, like Angna Enters, you were a dancer and an aviator.

You know why I said aviator? Because I couldn’t say angel. I love the idea of flying. We dream about flying.

I’m always interested in artist groups and movements, like Monster Roster, with which you were associated in postwar Chicago.

That’s the most terrible expression. It’s in a way all influenced by Leon Golub [a Chicago-born and-educated artist]. But I didn’t go to the Art Institute. My meeting with Leon is very important. Leon wanted to meet me because he loved my work. I was very, I don’t like the word precocious, but let’s put it this way: the day I started making art, I said, this is the day it starts. I had many days like that. I made these wonderful paintings in 1948. I went to the New Bauhaus school and the teacher showed pictures by Kurt Schwitters. And I thought, “Ugly, ugly — what’s that?” But, within three months, I gained my insight into what modern art was. It happened very fast. I decided I wasn’t going to stay in school because all the beautiful art is on the sidewalks, in the cracks, and in the cobblestones. I’m just going to follow that for the rest of my life.

Figure Descending Staircase (detail), 2010. Tin and wire. Courtesy of Ortuzar Projects.

Joan Jonas told me that you started to do these metal sculptures that were handheld yet portable. How did you invent those?

It was the time of the women’s awakening, and I was very bored by that, because I had had my awakening and then some in that time. And here comes the women’s movement pestering me. But I thought, “Why don’t the women just make a monument to themselves? Something so big, so powerful that it’ll shut the men up for good.” So I made these drawings of this monument that women should make to themselves. And then here I was traveling back to Mabou and I thought, “Oh, well I can’t make it here, so I’ll just make them small.” I did try to make the head — I went to the foundry in Lippincott. The head was going to have mechanics. You turn the crank and the tongue moves. I was not successful, because they couldn’t put up with me.

But it’s fascinating that this came from monumental drawings. From macro to micro. You have lots of other big sculptures that are unrealized. I’m always interested in unrealized artist’s projects, because we always know about architects’ unrealized projects, since they always publish them. I mean, Louise Bourgeois had done all these books, but no one knew that what she really wanted to do was build a little amphitheater. What are your unrealized projects and dreams?

They go by so fast. You have ten a day. Yesterday was a turning point. I went to speak with some high-school students, and it shook me up because I realized, my god, they’re 17 or 18 years old. That’s the most important time of adult life. And I wasn’t responsible. I regretted that I wasn’t sensitive to that important moment. It jolted me. And I was very grateful for that because I’ve been very spoiled by this show at Ortuzar Projects. It’s put me into a strange condition of being important, and I’ve been patting myself on the back for about a week now. It’s very unhealthy. But when I saw these high-school students yesterday, it brought me back down to earth. I’m on a new trip. I’m not glib anymore. I have to come down to earth. Because how long can you go around thinking about flying and your hands and things like that? I should be finished with that.

Wake Up, 2015-18. Acrylic on paper, tin and metal collage. Courtesy of Ortuzar Projects.

Wake Up, 2015-16. Acrylic and charcoal on paper. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the artist 2016.137 © June Leaf.

Man (Dreaming), 2001. Acrylic and pen and ink on paper. Courtesy of Hyphen.

Going back to the mechanics of the head — you said the tongue moves. And in the exhibition, there was also sort of a sidebar mechanic. I worked in Paris when I was a student, and there was an old Singer sewing machine with a little manual next to it. And that inspired my Do It project, which is basically artists writing instructions, like manuals for artworks, so people can do it themselves. I’ve always had this fascination with sewing machines, and I read that it’s also an obsession of yours.

Maybe being under the table with that foot pedal makes me think of my mother, because I was there looking at her shoes and wanting to draw a shoe. I think later I superimposed those mechanics, because she was sewing by hand — the machine wasn’t there at all. I just think that’s such a beautiful fact of the foot, the woman’s foot maneuvering the treadle.

And you use sewing machines in your work.

I do. I wonder if I still will. It’s good to feel you’re at a new beginning, and that’s what I feel today.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a little book of advice to a young poet. What is your advice to a young painter?

Be brave.