Magdalene Odundo, Asymmetrical Betu I, 2010; ceramic.

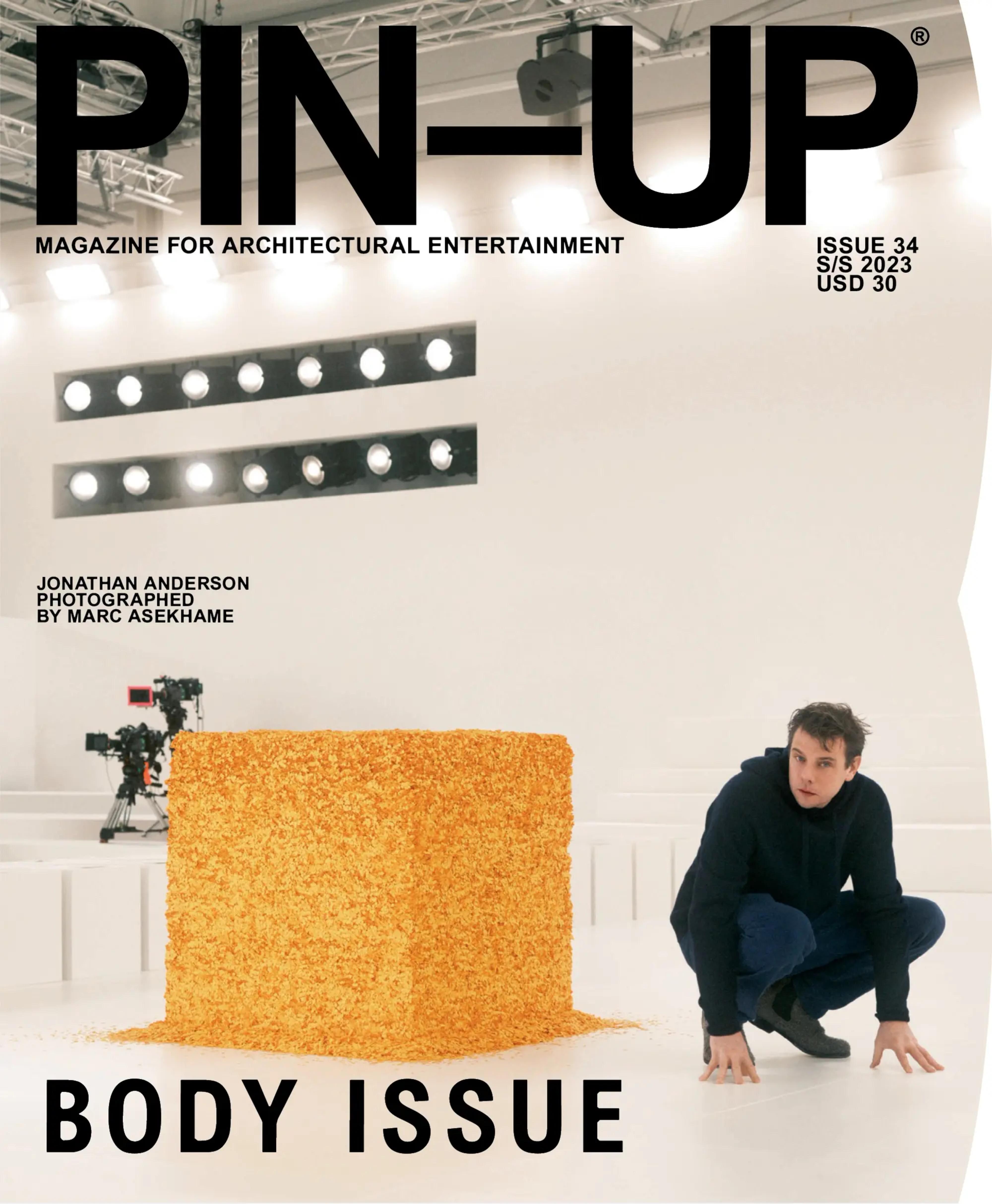

Jonathan Anderson photographed by Marc Asekhame for PIN–UP

In 2005, 20-year-old Jonathan William Anderson graduated from the London College of Fashion with a “messy” show in a nightclub featuring cabaret artist Justin Vivian Bond and musician-performer No Bra cavorting alongside dancers and overripe fruit. Eighteen years later, he is creative director not only of his own brand, JW Anderson, but also of Loewe, today one of the world's most renowned luxury houses. When Anderson got the job, in 2013, Loewe was a sleepy and rather bourgeois Spanish label mostly known for leather goods; in the decade since, thanks to his Midas touch, it has transformed into a key player in the industry, not just financially but also culturally. Constantly venturing outside fashion for inspiration, Anderson has set up countless collaborations with artists and others such as Lara Favaretto, the Estate of David Wojnarowicz, Julien Nguyen, Anthea Hamilton, and the Tom of Finland Foundation, to name but a few, producing exhibitions, books, design objects, and other cross-pollinated cultural artifacts. And if Rihanna’s pregnant Superbowl performance in head-to-toe Loewe are any indication, though the venues have gotten bigger since his graduation show, Anderson's knack for high-flying cultural mischief is as strong as ever. There’s also a quieter but equally sophisticated side to Anderson's reign at Loewe, namely the international Craft Prize, founded in 2017, which awards an annual 50,000 euros to exceptional artisans who “create objects of superior aesthetic value.” A keen collector of craft, particularly ceramics, Anderson is deeply fascinated by those who work with their hands. PIN–UP sat down with the Northern Irish designer as he was getting ready to judge the sixth edition of the Loewe Craft Prize presented at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York.

View of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize presentation at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, May 2023. Photo by Naho Kubota.

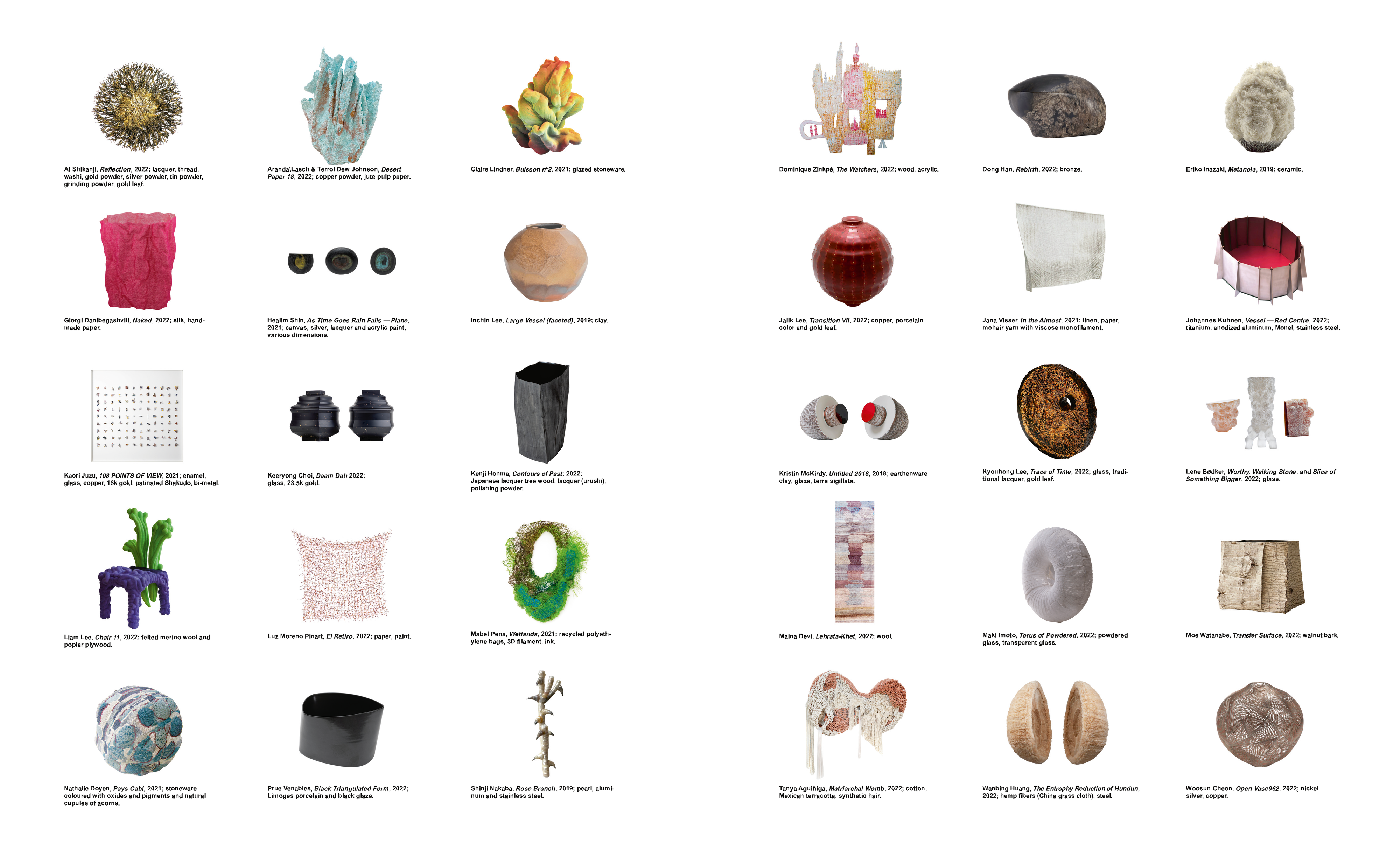

The finalists for the 2023 Loewe Craft Prize. All craft prize images courtesy of Loewe Foundation.

Felix Burrichter: The last time we met was right before the pandemic, at Loewe’s holiday party at the Ukrainian Institute in New York.

Jonathan Anderson: Oh, yeah, that was in 2019.

You personally greeted everyone alongside a woman I thought was your mother. It seemed so sweet. Only when she shook my hand and purred “Happy holidays,” did I realize it was Jennifer Coolidge!

[Laughs.] I mean, in a way she’s a mother to all of us.

One of the reasons I wanted you for PIN–UP’s Body issue is because of the way you work — instead of using sketches you often drape directly on the body. And in recent collections, especially at Loewe, you’ve also experimented with the silhouette, representing the human body in sometimes surreal and abstract ways.

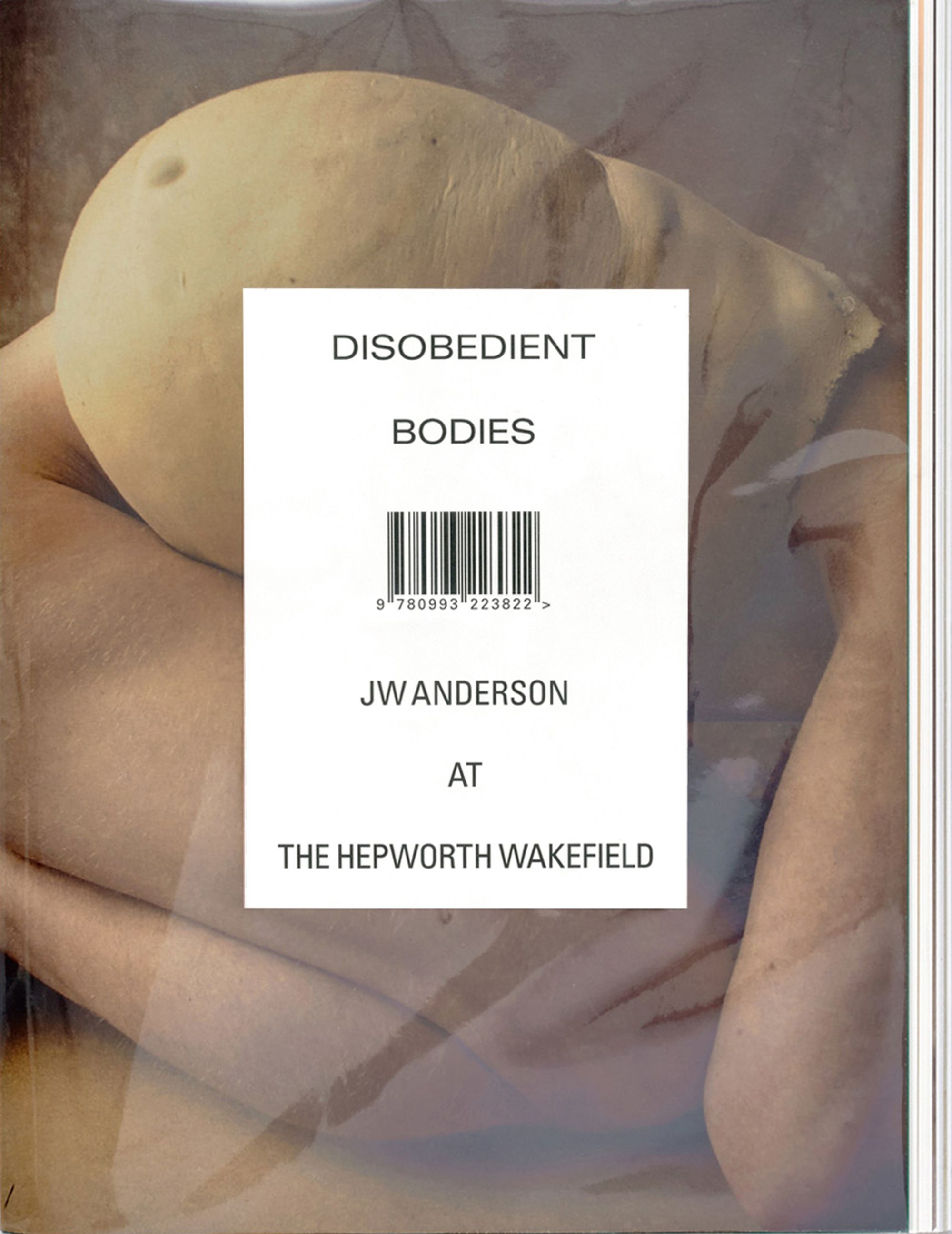

I actually did a show about the body in the U.K. at the Hepworth Wakefield called Disobedient Bodies [2017], which looked at different art practices across ceramic, sculpture, and fashion, including other designers like Helmut Lang, Issey Miyake, Vivienne Westwood, Rick Owens, Comme des Garçons, and less well-known figures like the artist Richard Tuttle. It was an exploration of how design, not just fashion, has coincided with the body and abstraction. The show was really a question: is fashion an art form? Because up until that moment, I was very much in the mindset of, “I work in fashion, it’s commerce.”

Where are you now in the mind-versus-body equation?

There are moments when I reject the body or have fantasies where it’s aspirational. Sometimes I want to abstract it, to play with its proportional line by breaking it up. For the show we just did, the body became a ghost-like figure, a reference to Gerhard Richter — he did a series of paintings I’ve always found magical, because from farther away the image of the body is in focus, but up close it becomes more of a blur or a silhouette. For me, it’s about moments of embracing the body while rejecting it at the same time. I've always held this idea that clothing is about covering the body, but, when you look at ceramic art, which has been one of my biggest influences, it’s about what’s inside the vessel. The ceramist Magdalene Odundo, who is a very dear friend of mine, makes these incredible vessels which were also part of the Disobedient Bodies exhibition. To her, the vessel is the body. A ceramic is usually built as a coil, or it’s spun so you end up with a void inside — and what you put into that empty interior becomes the emotional part of it. Or, if you take ceramists like Hans Coper, who looked to Cycladic figures, it’s the idea that you are reducing the figure to something. The emotional part is inside rather than decoration on the outside.

Magdalene Odundo, Asymmetrical Betu I, 2010; ceramic.

Gerhard Richter, Frau, die Treppe herabgehend (Woman Descending the Staircase), 1965; oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Art Institute, Chicago. © Gerhard Richter

Disobedient Bodies: JW Anderson at The Hepworth Wakefield, catalog by Jonathan Anderson, Andrew Bonacina, and OK-RM (InOtherWorlds, 2017).

You collect a lot of ceramics. Do you go through phases of what types you buy?

I collect a very tight group of ceramists, mainly British or African. Also historical pieces, some of which are anonymous. There’s Jennifer Lee, who, in comparison to Sara Flynn’s rather sculptural work, makes vessels that are more environment, while Magdalene Odundo's are more about the body.

Did you discover their work through the Loewe Craft Prize?

I knew about some of them before the prize. Like Sara [Flynn], for example, who’s from Ireland — I discovered her work when my brother got married in Cork. I went into a shop to get a gift for him, but ended up buying one of her pieces for myself. I just liked the form of it. Hans Coper too, who’s probably one of the greatest ceramists of the 20th century — I think he changed the idea of contemporary ceramics... Who else? John Ward, whose work is more decorative, more about optics. It’s a very tight group and I will bend over backwards to get a ceramic from any of them, more than I would for a painting. Especially from someone like Magdalene — I think she’s one of the greatest living artists.

What is it about ceramics that draws you in?

Though I understand the process, I could never do it myself. And I’d never want to — I live the idea of the unknowingness of it. I have tried once but I feel like I would make awful ceramics. I like to be a fan of someone’s work and really kind of obsess over it.

Jonathan Anderson photographed by Marc Asekhame for PIN–UP.

Jonathan Anderson photographed by Marc Asekhame for PIN–UP.

What obsessions do you have besides ceramics?

I’m a constant editor. I can get bored of things. I feel like I’m always editing down what I collect or what I do. I like to reduce. Thankfully, as you get older, your taste becomes more refined. I think my obsessions fall into different categories. There’s both the historical and the modern. When I look at the art and ceramics I collect, there’s a psychological pattern to it too. I might desire the texture, or the person in it as a kind of friend, or I might even desire them sexually. Paul Thek, for example. Had I met him, I probably wouldn’t have liked him, but there’s a sexual tension in his work I really love. Another thing about collecting is you need to figure out where to keep it all. I’m building a house in London at the moment with the architect David Kohn. I’m a house person — I love staying home. I could stay in the house for two weeks and it wouldn’t bother me. But I’m trying to build one that can deal with the element of boredom. When you see things too much, especially when you’re creative, your mind can get trapped in a certain idea. We’re trying to work out a way to create modular storage so I can easily rotate things. The house won’t be done until 2025, so there’s still some time to figure it out.

You divide your time between London and Paris?

I always live between the two. But I like the idea to create more definitive spaces. l’ve reached a stage where I’ve built Loewe as a brand, and I’ve never enjoyed it so much. Loewe is a vessel. It’s not my personal vessel, but I was able to pour everything I wanted into it, and the brand has grown enormously. The number of stores is growing, people are able to pronounce the name, and understand the complexity I built into it. In the beginning, it wasn’t so straightforward — I remember sitting with Delphine Arnault and saying that luxury was dead and that I wanted to build a cultural brand. That was ten years ago, and it was a risky proposal for a label no one really cared about.

When you launched the Loewe Craft Prize in 2017, did you expect it to become so important?

It was a fantasy I’ve always had because I collected craft. And I felt there was never a platform for it. I was very lucky that LVMH let me do it, because running a prize is incredibly expensive. We want it to be something that helps launch people’s careers. I think it’s becoming one of the most important craft prizes in the world. And it came out of a fashion brand, which is highly unusual.

Has work from the Craft Prize ever trickled down into your Loewe collections?

It never really does. Sometimes we do a collaboration with one of the craftspeople, for example lacquer artist Genta [Ishizuka] — an amazing handbag and some jewelry. We did dresses with [Takuro] Kuwata. And Loewe has a collection of contemporary craft. I think we’re building something very current and incredibly important.

The results of the seventh edition of the Craft Prize will soon be shown at the Noguchi Museum. What are you particularly excited about?

The country we host it in usually ends up with the most submissions, so I’m really excited about discovering all the U.S. entries this time. We did past editions in Korea and Japan, where there’s such an amazing respect for craft — artisans are seen as national treasures in the same way that contemporary artists are revered in Europe and America. That was one of my reasons for founding the Craft Prize — I was looking at people like Magdalene Odundo ten years ago and thinking, “She’s just as important as any contemporary artist out there, why is there no platform for her?”

Metanoia (2019) by Eriko Inazaki; ceramics; the winning work of the 2023 Craft Prize.

The Watchers by Dominique Zinkpè; wood, acrylic; runner up for the 2023 Craft Prize.

Transfer Surface by Moe Watanabe; walnut bark; runner up for the 2023 Craft Prize.

Eriko Inazaki and her winning ceramic, which was “created through an accumulation of miniscule forms that coalesce across the work’s crystallied surface.”

Moe Watanabe and her walnut bark box “that pays tribute to the cyclical turns of the seasons and recalls the ancient Japanese tradition of Ikebana vase making,” one of the runners-up of the prize.

Dominique Zinkpè and his sculpture The Watchers, one of the runners-up of the prize. Made up of individual pieces of wood, “the assemblage of small Ibéji figurines evokes traditional Yoruba beliefs connected with multiple births.”

What is your relationship to the things you design yourself? Do you have them at home?

Not really. It’s just too personal. I once had one of these bedside tables that were chairs from one of the shows, but I had to get rid of them because they were reminding me of the show. At the moment I have the original bust of Rihanna from the Super Bowl on my mantlepiece. But that’s different — it falls into the zeitgeist.

It sounds like you’re more vulnerable with things that aren’t related to fashion?

It’s possible. I think because I deal with fashion on a daily basis, it’s less precious to me. I also don’t really collect it. I’m surrounded by fashion, and of course there are things I made that I love, but I don’t have them in my house. I have them in a storage unit.

Do you collect design?

I actually find design furniture very difficult ultimately. I don’t have any in my house. I struggle sometimes when I go to houses full of it where there’s nothing warm, tangible, or relatable.

Jonathan Anderson photographed by Marc Asekhame for PIN–UP.

I heard you’re into Baillie Scott.

I love Baillie Scott and a lot of the Arts and Crafts. I would love a very good Rennie Mackintosh chair. For me, Charles Rennie Mackintosh created the domestic white space. He looked at the Viennese, and then took it to another level — just painting everything white and leaving only a few geometric lines. I like that kind of furniture, but I also like very primitive pieces, such as Welsh stick chairs. The traditions goes back a couple hundred years: people in the countryside made them from wood they found in hedges. I like when furniture gets that primitive. And some of them become very sculptural. We just worked with Welsh stick chairs in Milan for the Salone del Mobile, dressing them up in different materials. We turned one into a fur chair, and for another we move wove those thermal blankets you use to keep warm during a marathon. We did one with bailing twine used on farms, and of course we also used leather, as well as having Lloyd Loom chairs.

What kind of furniture do you have at home?

I like very good antique Irish or English furniture. There’s a skill set to those pieces that doesn’t exist anymore. Nothing beats a 15th-century refectory table or a Chippendale from the 1730s. In America, Donald Judd made the best mix: when you look at his Marfa studio or his personal homes, you’ll find a lot of 17th-century furniture combined with the sharpness of his own sculpture and furniture.

I was really surprised to hear about your personal connection to Ibiza.

Yes. My parents have a house there, and I’ve been going since I was four or five. That’s why I wanted Loewe to buy Paula’s Ibiza, a brand which started there in the 70s. Ibiza was the only connection to Spain I had. Before interviewing with Loewe, I’d never been to Madrid, and only once to Barcelona. I felt very provincial. But in Ibiza, I know every corner. I always feel a sense of relief when I get there — it reminds me of being a kid, finishing school and going there for the summer. You’ll be like, “Oh my God, we’re off for a month!” And at the same time there’s the most incredible sexual tension. There’s something about the light, something about the beach. And I quite like that element of escapism. I remember as a kid going to a nude beach with my parents — growing up in Northern Ireland, where it’s gray most of the time, that was just so liberating.

Would you say Loewe taps more into the Jonathan Anderson fantasy, while your own brand is the Jonathan Anderson reality?

A little bit. Loewe is this fantasy of a house that’s not mine. Whereas with JW Anderson it’s a love-hate relationship because, ultimately, it’s a relationship with myself. In menswear especially, it’s a strange fantasy of what I would love to be able to pull off. When I was younger, I loved wearing fashion. As I get older, I wear less of it. But there’s nothing more exciting than looking at a model in front of you as you’re doing the fitting, seeing a character come to life, and thinking, “I want to be that person.”

You were so young when you started JW Anderson in 2008, only 24.

Yes. But I think there was a culture of that in London at the time. Whereas if I was coming out of university now, I’d probably try and get a job somewhere first. Back then London wasn’t so expensive and you could still squat. Everyone would help each other out. When I look back, I’ve no idea how I would even have got a job because I was a mess. Everything was a mess. But I never found it depressing. It was an amazing moment.

Loewe, stick chair, 2023; wood, paper loom. All work images courtesy of Loewe.

Loewe, stick chair, 2023; wood, shearling.

Loewe, paper loom chair with mushroom motifs; paper loom.

Loewe, stick chair, 2023; wood, laminated foil.

Can you tell me the story about how Justin Vivian Bond performed at your graduation show?

I was dating a friend of theirs at the time, and we saw Viv at Carnegie Hall. I remember buying the CD and listening to it on repeat. I think that show is still as relevant today as it was then. I told Viv that I had to do a graduation show but didn't want to do it at the school. Instead I wanted to do it at this nightclub, with all this old fruit and other stuff that was being dumped. And we had these tables with guys lying on them while Viv sang alongside No Bra. I remember it turned into an absolute mess and I was just screaming at people at the end of it. I'm kind of glad there are no pictures. [Laughs.]

No Instagram in those days.

No — I remember printing out pictures from a night out. No one took selfies either — you didn't have 10,000 pictures of yourself on your phone. Now we're in this weird moment where we self-censor, which is the craziest thing. The most quintessential part of this to me is the selfie. People take it from a certain angle because they want to show a prescribed version of the same thing — they want to be part of the status quo. But how can you still be creative if you don't take the risk of looking bad? I'm hoping it will change again one day because it might actually help fashion and contemporary art. Right now, a lot of things look very good on Instagram, but when you see them in reality the surfaces are really bad.

I think the era of oversharing is over. I'm noticing people deliberately logging off or going silent on Instagram.

I don't believe in a blackout either. Part of me feels that we are in a sharing culture. I do believe in democratizing things. Back when I started, you had to rely on editors who decided to cover you. What I like about now is being able to do whatever I want without asking permission from big editors. I'm able to talk to people directly, without a wall.

What's your relationship to your own body?

I don't like mirrors, for example. Because that's what we look at in the morning, a carbon copy of ourselves. Like normal people, I love my body in the summer and hate it in the winter. I always wish I was something I'm not. It's the normal thing. But I'm at one with my body. I know what I look like, and I know where I am in the world of aesthetics. I just really don't like bright light, overhead light, or too much light in the bathroom. And there's nothing worse for me than the lighting of airplane mirrors. It's fine for it to be a bit darker and to have a non-reality of what I look like. So I'd say my relationship with my body is that I'm at one with it — but ultimately I'm a perfectionist, so I wish it was perfect. [Laughs.]