Niels Olsen: Your design method is based on communication, which is a key part of the process of creating museums and cultural institutions today. The idea of the museum as a hermetic treasure box can be challenged if the building process is guided by discussions with local communities rather than just with clients and stakeholders. In your writing, you also describe this aspect of your practice as a resistance against architecture’s absorption into the visual media machine from the 1980s onwards. The Shōnandai Cultural Center, a hybrid of a children’s museum, a theater, and a garden, embodies a playful openness that stands in complete contrast to Western models of cultural institutions.

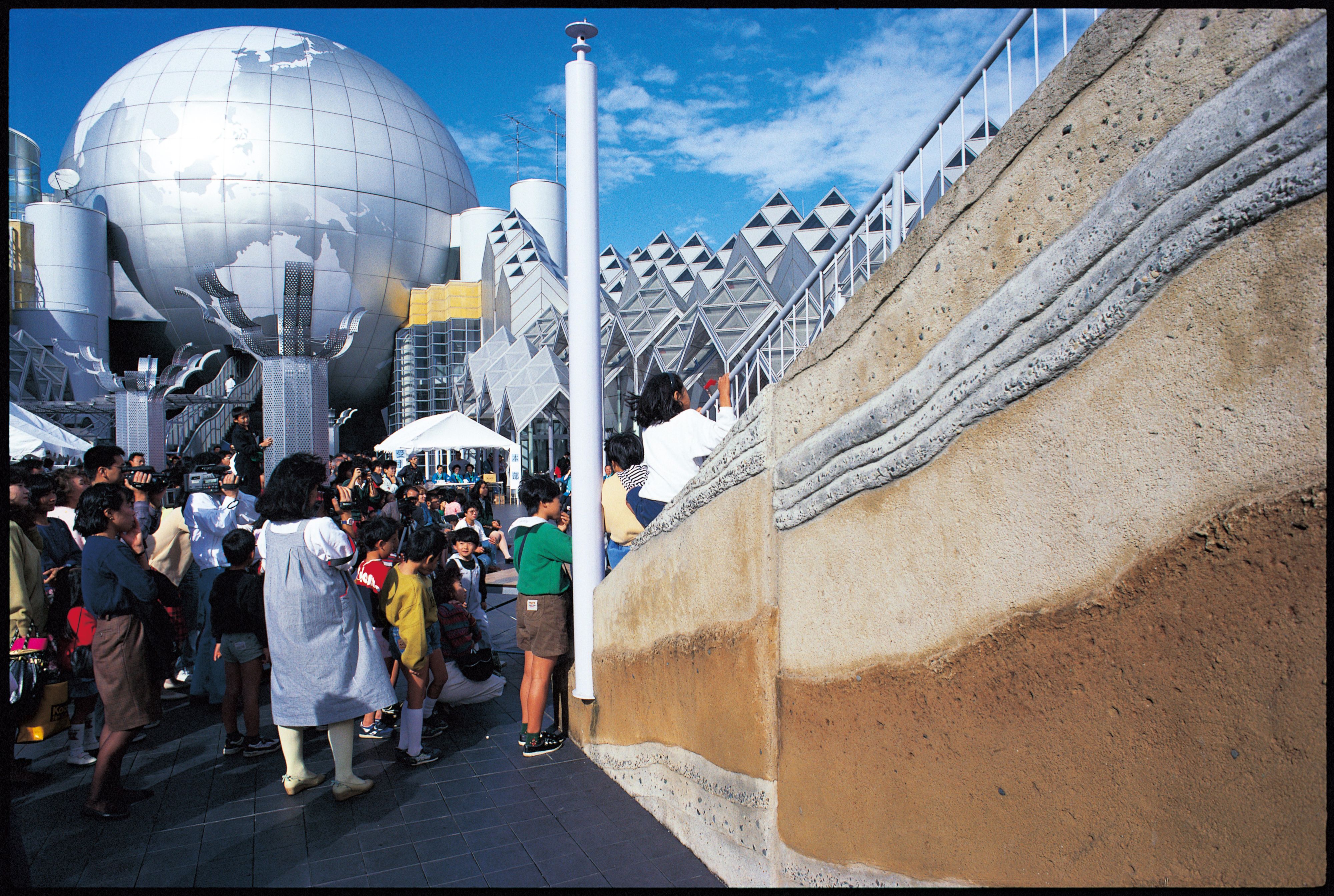

Itsuko Hasegawa: While Western discussions of democracy and fairness regarding common space have inspired me, Shōnandai was influenced by my childhood experiences with the traditional Japanese way of thinking about community space. Yaizu, my hometown in Shizuoka prefecture, is a fishing town a little southwest of Tokyo. When there was a big catch, everyone gathered in the garden to cook together. At festivals, children would dress up in costumes and take the stage, and at the beginning of spring everyone would gather at the beach to celebrate. Semi-outdoor shared spaces such as Shōnandai are rooted in the sense that these people have come to terms with the pleasant climate and culture they have inherited. Before Shōnandai, most children’s museums in Japan were run by big corporations and related very little to how kids actually played. During Shōnandai’s planning stages, many elderly residents were afraid about the idea of a large-scale modern building in their neighborhood. For this reason, I decided to locate most of the public programs on the lower level, basically below ground. I designed all the pavilions and the furniture, and detailed all the railings, signage, and exhibition displays. After I completed the building, I became the director of the children’s museum for ten years. A lot of work was involved, from developing exhibits and catalogues to planning events, ordering ethnic costumes and hats for children, and adding and fixing exhibits.

NO: Usually with a public building that size, the garden becomes a separate typology from the building. At Shōnandai, the reverse is true: the building is defined by the garden and landscape. In what way does this express your idea of architecture as second nature?

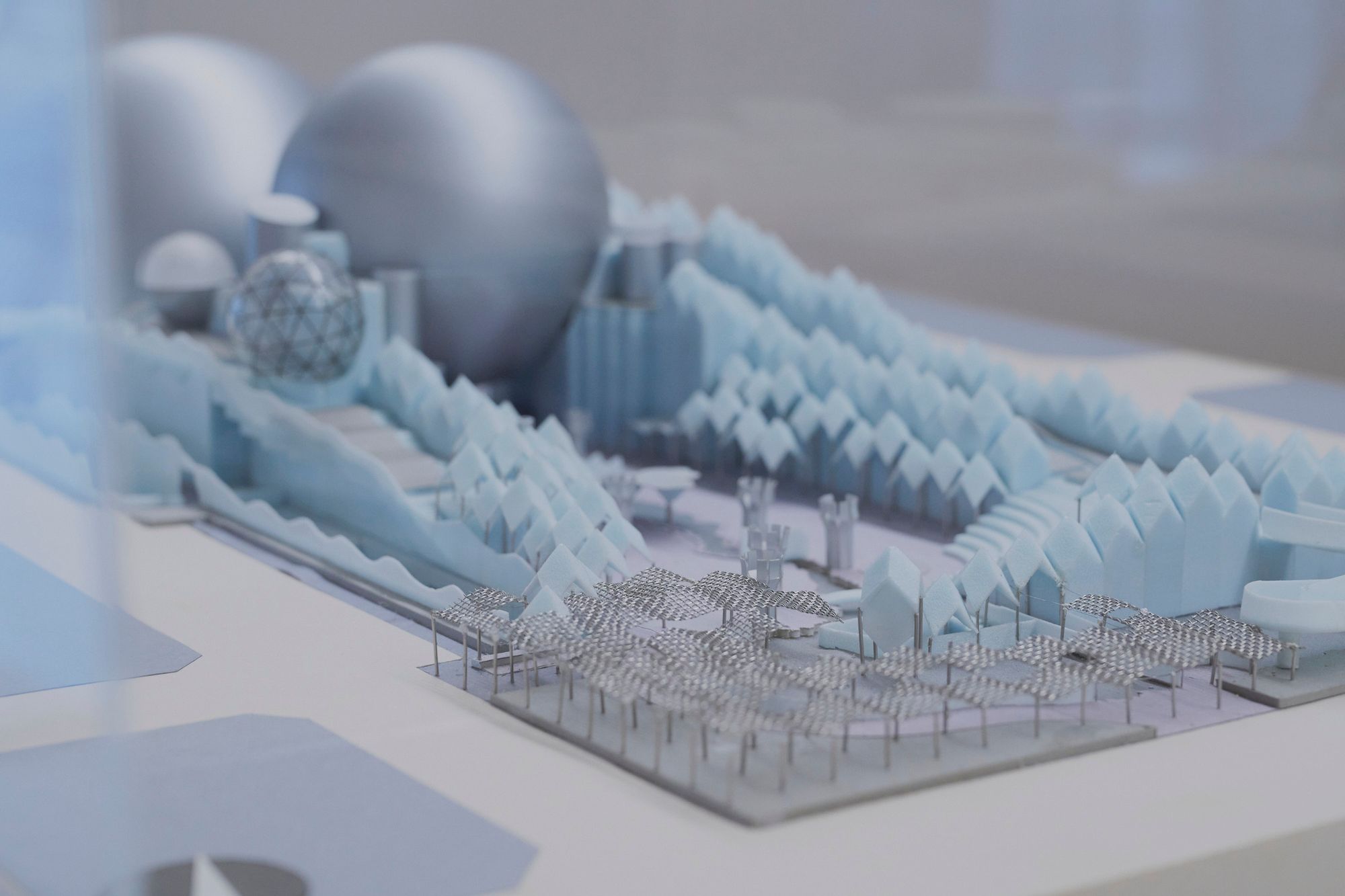

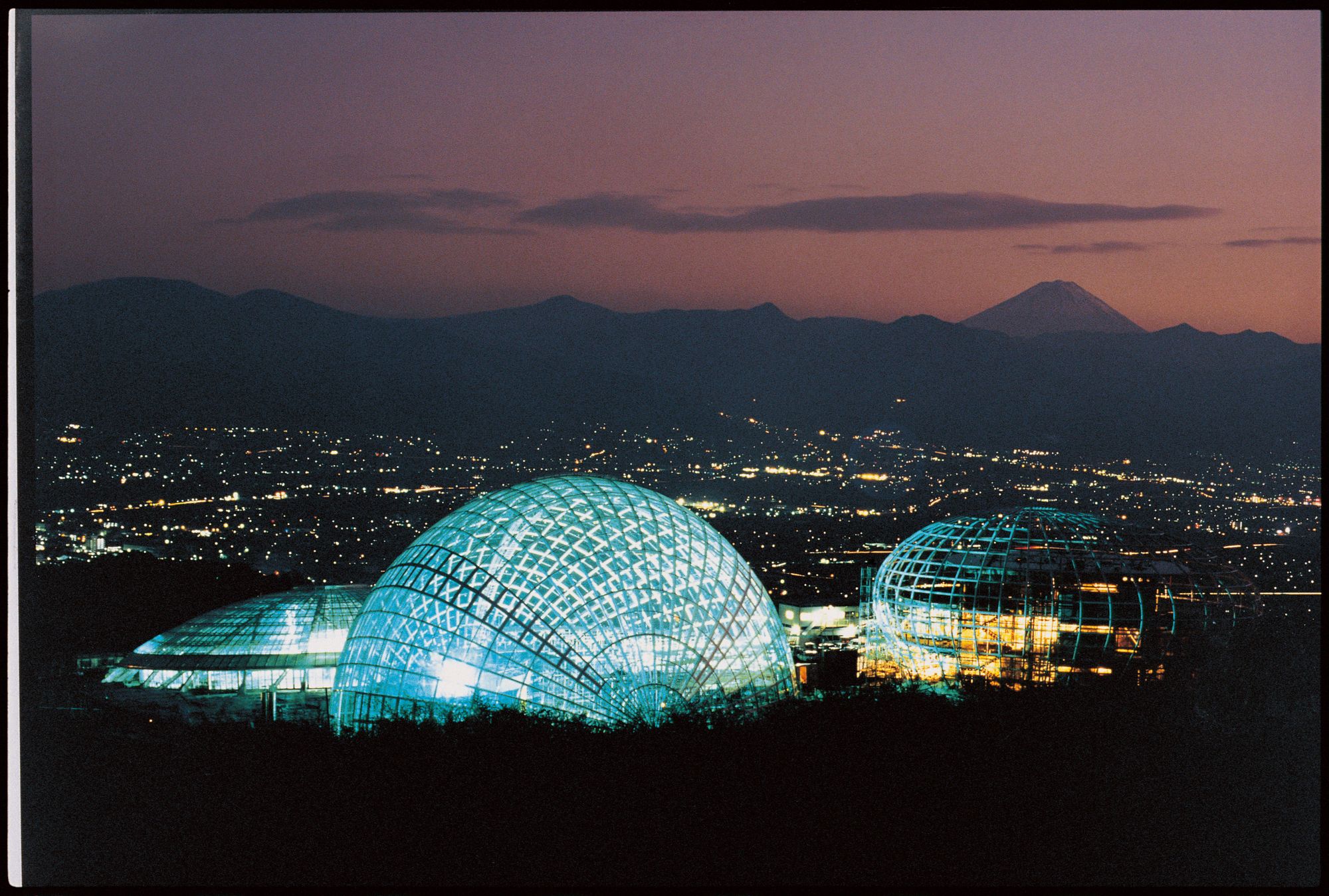

My idea of second nature is maybe different from other people’s use of it in literature. When Shōnandai was commissioned, in the late 1980s, there was a little hill, a mound, on the site. During the competition, that mound was destroyed. I proposed that we create a new mound to reflect the site’s history. Many people questioned my proposal and wondered if it was necessary to recreate this hill, and that’s when I formulated my idea of architecture as second nature. It’s an idea of maintaining and preserving local communities’ lifestyle, the way residents and the elderly live. It shouldn’t be mistaken with tradition. In this sense, my design also reflected my doubt about whether we should place a modern building on that site. It was much more about creating a park for the community instead of a modern monument. This idea also has to do with my upbringing. Because of World War II, my mother and I left the city and started living in a house in the countryside. Until I was eight, I grew up with the ocean in front of me and the mountains behind. I spent my early childhood in the midst of abundant nature, gazing at the sea, the sky, the moon, and the mountains. My mother, who grew up in a temple, taught me Buddhist ways of thinking, and we drew wildflowers and collected plants together. Until junior high school, I wanted to become a botanist. So, when I thought about what comfort was, I had the idea that comfort equals nature. I have been pursuing architecture as a new nature — architecture as topography, and landscape architecture as a second nature.

NO: To hear that your mother drew wildflowers is very interesting. I’m curious about your hand drawings, how you make the sketches to illustrate your ideas.

She made her own Kimono and my clothes by dyeing the pictures she had drawn on the canvas. My idea has always been to connect nature and architecture, to make them into one. This really began when I started working and was required to think about public institutional buildings. Shōnandai was the largest piece of land I had worked on, and when you consider how the architecture should sit on a large piece of empty land, you need to start thinking about the relationship between inside and out. Sometimes botanical representations helped me conceptualize that.

NO: The notion of care is significant in your work. Could you tell us more about the Shiranui Hospital, Stress Care Center in Omuta, Fukuoka Prefecture, which you completed in 1989. It proves that hospitals don’t just have to be big boxes — it’s organized a bit like a village, with lots of smallish linked buildings.

I’d been talking to young doctors who were all complaining that in the Japanese hospital system you have these beautiful locations but you can never go outside. We chose a seaside site, despite initial reluctance from some stakeholders — they thought patients might jump into the sea. Based on my own childhood, I knew it would be therapeutic because of the sun glistening on the ocean, the tides rising and falling, the rhythmic sound of the waves, the scent of the sea reaching each room, and the sound of raindrops falling on the roof — all of this would offer a source of comfort in the face of long-term illness. The project follows the seashore in the shape of a long bow, and takes the form of several small houses arranged in a row. The corridors have a varied appearance, and each room faces the ocean. Between the rooms are passageways leading to the balcony, thereby allowing the wind to enter and connecting the houses to the sea. The furniture is movable, so each person can control the degree of openness according to his or her mood of the day. It was a very low-cost project, built by local craftsmen using local materials — somebody criticized it as looking like Asian informal urbanism!