Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

Conceived by the artist Sarah Ortmeyer and Karl Kolbitz, ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow) is a Vienna memorial for homosexuals persecuted during the Nazi Era. It was inaugurated in the summer of 2023 near the Karlsplatz, one of the busiest squares in the Austrian capital. Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

In 1943, after being charged with “fornication against nature,” Nazi guards transferred 21-year-old Franz Doms to a death-row cell. Aside from the usual prison fixtures, Doms saw more alarming personal effects: the toothbrush and meal scraps of a prisoner who would not be returning. As journalist Jürgen Pettinger describes in his 2021 book Franz, a fictionalized biography of Doms, the young Austrian was also distraught by the grayness that surrounded him as he languished in prison — dim winter days, indeterminacy, and the ashen wall paint that would bleed onto his uniform.

Doms’s court records feature prominently in a 2018 report by QWIEN (Zentrum für queere Geschichte) outlining how the history of the persecution of queer Austrians by the Nazi regime might inform a contemporary memorial. In 2020, the City of Vienna announced an open call soliciting proposals for such a memorial, and the winning proposal, by German artist Sarah Ortmeyer and editor/art director Karl Kolbitz, was unveiled during Pride in 2023. ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow) comprises six arched pipes, a rainbow in six shades of gray, standing on a low, white plinth along a busy walkway of Karlsplatz. As the sun moves across the sky, the arches’ shadow slowly drags across the ground.

Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

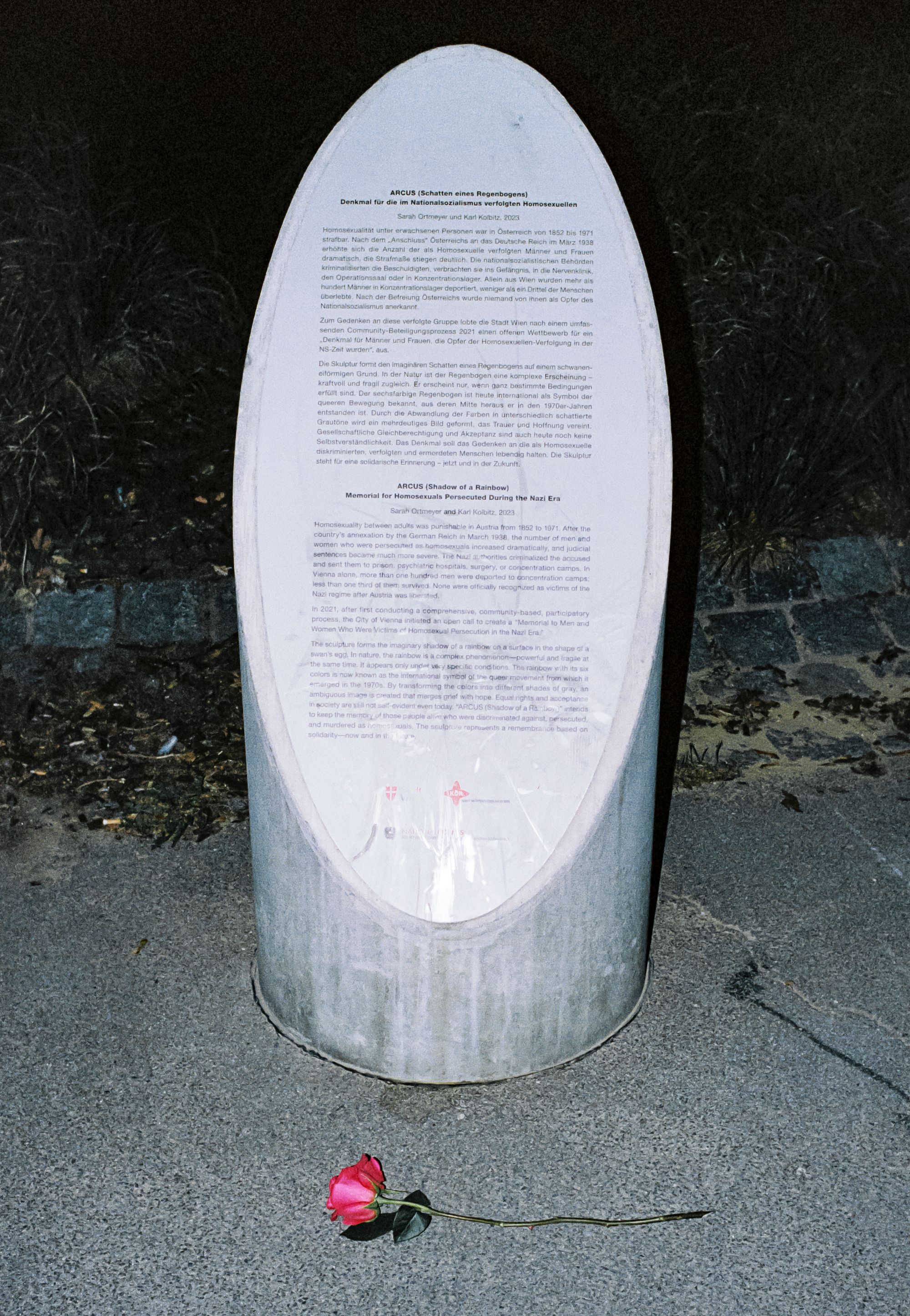

The egg shape is a recurring motif in ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow) and in Sarah Ortmeyer’s practice, where the artist often works in material translation, reworking the silhouettes of devils, palm trees, and rainbows into monochrome forms. Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

It was while working on the group exhibition Political/Minimal in 2008 (at Berlin’s KW Institute for Contemporary Art) with fellow artist Terence Koh that Ortmeyer learned of Rudolf Brazda, the last remaining Holocaust survivor victimized for homosexuality. With Brazda’s legacy in mind, the artist, who has long empathized with this history, approached Kolbitz in 2020 to collaborate on a memorial competition entry. Together they reworked Ortmeyer’s 2019 painting — also called ARCUS — in which black arches are rendered in minimal paint strokes.

A nearby plaque explains the presentism of the rainbow symbol (as opposed to the pink triangle) and recounts Austria’s criminalization of homosexuality from 1852 to 1971, and the Third Reich’s acutely violent oppression. The plinth, as the plaque asserts, is in the shape of a “swan’s egg” — an important detail to Ortmeyer, who often expresses herself through metonym. Playing with the ovoid shapes that define Karlsplatz from a bird’s eye view, she adapts them into the shape of the plinth, the plaque, and even the screws holding the piece together. She asserts that this form is meant to convey a feeling rather than a history. Ortmeyer often works in this mode of material translation, reworking the silhouettes of palm trees, rainbows, and devils into monochrome forms.

The rainbow was first associated with queerness in 1978, when Gilbert Baker was commissioned by Harvey Milk to create a new symbol for Gay Freedom Day. In a speech given that day, Milk proclaimed to gay San Franciscans that, “We are not going to sit back in silence as 300,000 of our gay sisters and brothers did in Nazi Germany,” calling for the community to take action beyond self-righteousness, and evoking what Primo Levi called “the gray zone.”

The reference to Gilbert Baker’s 1978 rainbow flag was important to Ortmeyer and Kolbitz because it creates something that is “accessible and that people are drawn to,” according to Kolbitz. Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow). Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

That Baker and his collaborators settled on the medium of a flag, a symbol once the provenance of the military and the modern nation-state, is particularly compelling. For Kolbitz, the referent of the rainbow flag was important “to create something that is accessible and that people are drawn to.” But how do we read this symbol today, its language born from queer solidarity yet so often imposed from the top-down? Gorgeous queers wear it as a tube top on June afternoons. Bigots light it on fire, fearing it like an idol with the power to turn their children gay. Liberal corporate executives and Western politicians wave rainbow flags as they perpetrate genocide, Islamophobia, and the expansion of capital. Why, it must be asked, is the rainbow adaptable to both a Holocaust memorial and to Skittles’ Pride campaign? In a minimalist idiom, the sculpture stretches a threshold between these contradictions, collapsing not the space but the time that separates them.

ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow) is meant for the transient, casual spectator rather than the pilgrim. In the brief for the competition, the City of Vienna stipulated that the memorial not include any seating due to Karlsplatz’s “history as a drug-dealing place.” It’s a candid admission for a city agency, sounding the familiar dog whistle that defines the hostile architecture of the neoliberal park. Kolbitz and Ortmeyer pushed back on this requirement, imagining the memorial instead as “a gathering of people.” Ortmeyer is moved when children identify it as a rainbow, or when queer people lay roses at its base. As people claim it for themselves, the sculpture becomes part of daily life. Historian Andrew Shaken notes that, despite being “imbued with high feeling,” memorials always become inextricable from life in this way.

Modern queer symbols like the rainbow have a dual effect: they create legibility and draw attention, while simultaneously flattening the messy realities of queer experience into homonationalist photo ops. The memorial’s inauguration coincided with the Austrian government providing modest reparations to queer people criminalized by the state in the last century. ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow) facilitates this tangible movement away from the myth that Austria was an innocent victim of the Third Reich, refracting the lights and lives of Franz Dom and more of the 1,200 queer Austrians who were unrecognized by the state for too long.

ARCUS (Shadow of a Rainbow). Photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.