FRONT TRIENNIAL 2022: TOWARDS A NEW DISCO

by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron

Jace Clayton, 40 Part Part, 2022. Installation view, Cleveland Public Library, July 16–October 2, 2022. Photo: Field Studio. Commissioned by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art and the New York Philharmonic. © Jace Clayton.

On the opening day of Cleveland’s FRONT Triennial, I walked into the vaulted reading room of the Cleveland Public Library and plugged my phone into a jack on a pedestal encircled by 40 speakers. I flushed as the bhangra beat of Britney Spears’s “Boys” turned heads.

I’d been here before. Not inside the Walker and Weeks’ Beaux Arts monument, but rather surrounded by sound in Janet Cardiff’s The 40 Part Motet at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale. Yet unlike the choral trance that lifted my consciousness in the gritty Arsenale, here in Cleveland it was my own Spotify playlist brazenly jolting the Stoppino-clad walls. Jace Clayton, who designed 40 Part Part as an open-source remix of Cardiff’s Motet, glanced over, with tender concern as I became the novice swaggering onto the high dive.

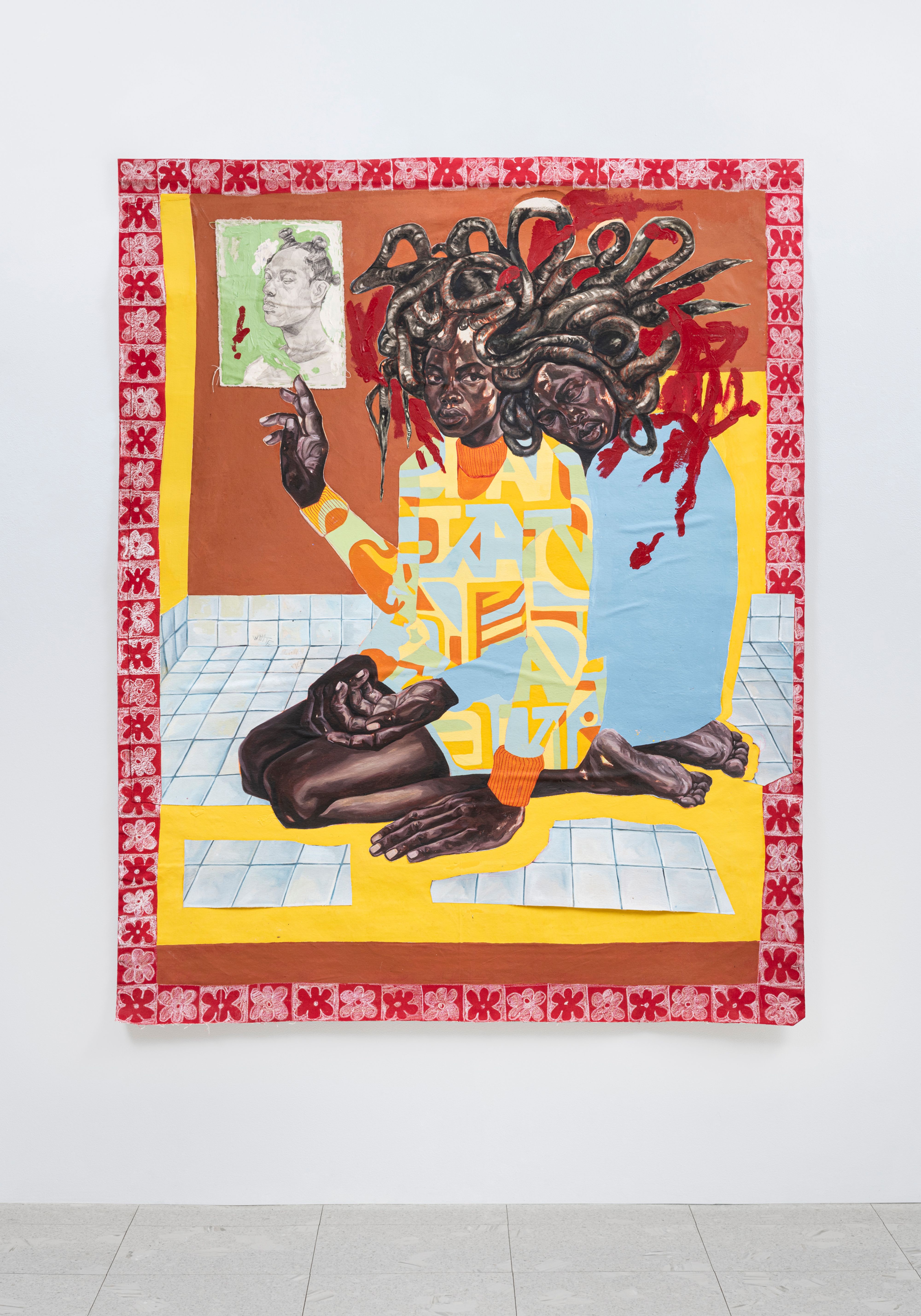

Alexandria Couch, It’s Alright: You Can Close Your Eyes for This One, 2021. Photo: Field Studio. © Alexandria Couch.

This was FRONT’s unifying motif: artworks provoking improvisation in public spaces — a library, a park, a plaza, a church – bristling against social codes; art asking its audience to dive in. Titled Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows, a phrase borrowed from a 1957 Langston Hughes epigram that measures the paradoxical cynicism and optimism of the human condition, the Triennial’s second edition spans Cleveland and neighboring cities, installing 100 international artists across 30 sites, each contribution a play on the supposed salvational qualities of art.

Artistic-directed by Prem Krishnamurthy, an award-winning graphic designer, curator and creative strategist, FRONT convened a range of practitioners ranging from performers to architects to represent frameworks for healing, revelation and exchange. While this running thesis of catharsis is inseparable from the concentrated distress of the pandemic years, it also tracks with Krishnamurthy’s broader practice as a creator known for disrupting protocols in pursuit of connection. In fact, as any good designer would, he has constructed an identity around enthusiastic exorcisms of self-consciousness: Krishnamurthy’s Present! series works through uncomfortable interdisciplinary arguments in real time; his P!DF digital publication evolves as information changes; a night out with Krishnmurthy almost certainly ends with new friends and mandatory karaoke. He once invited me to participate in a program through Berlin’s KW Center for Contemporary Art. I was informed upon arrival that I would be competing live with another curator for the archive of a Turkish graphic studio. Not to worry — octegenarian graphic design hero Karel Martens would be on my team.

From left: Paul O'Keeffe, In Memoriam (And a Beautiful Silence Consumes My Body), 2020–22; archival materials pertaining to Art Therapy Studio; Audra Skuodas, Sacred Spaces / Forgotten Places #4, 2001. Installation view, Transformer Station, July 16–October 2, 2022. Photo: Field Studio

Krishnamurthy’s cross-pollinating impulses animate FRONT’s interwoven pedagogy of communal transformation. From an interpretative strategy that leads with questions rather than answers to an emphasis on new commissions that center present-day and historic cross-disciplinary collaborations, FRONT prioritizes intersectional relationships and experiments. What struck me in particular when visiting the opening events was a thread of performance-centered works, like Clayton’s 40 Part Part in the library, that choreographed encounters with music at various sites in and around Cleveland.

In Akron’s Lock 4 park, part of a national creative placemaking endeavor funded by several foundations, Swedish architectural collaborative Dansbana! installed a public dancefloor. Part of an ongoing project to embed Situationist-style space for play and release within cities, architects Anna Fridolin, Anna Pang, and Teres Selberg met with local dancers and cultural organizations to inform the colorblocked design —part-porch, part-playscape — housing Bluetooth-connected speakers that enable anyone to initiate an impromptu fete.

Top: Kameelah Janaan Rasheed, This Sentence Began on September 27, 2020 and May Never End (detail), 2022. Bottom, from left: Christopher Kulendran Thomas, dataset#2-run#8-network_10996-seed_1112.png; dataset#2-run#3-network_01025 2-seed_3342.png; and dataset#2-run#8- network_10996-seed_1705.png, all works 2022. Installation view, Transformer Station, July 16–October 2, 2022. Photo: Field Studio

Martin Beck’s Last Night, a film that surpasses the 13-hour mark, soundtracks the setlist from the last party house music impresario David Mancuso threw at his storied Loft on June 2, 1984. With the Loft, Mancuso designed an equitable, anticapitalist and safe space to be transformed through dance. Influencing DJs from Frankie Knuckles to Victor Calderone, Mancuso fathered the now-ubiquitous style of spinning that crescendos over the night to synchronize a community through rhythm. He is also the inspiration for Louis Vuitton’s Pre-Spring 2023 collection, the last conceived by Virgil Abloh, whose experience as a DJ predated his work in fashion. Beck’s homage for FRONT was installed in West Cleveland’s Bop Stop. Situated in a neighborhood known for its historical ties to the LGBTQ Civil Rights Movement, the mid-day jazz club — empty, dark, and stripped of its decor — creates an elegiac ambiance for Beck’s puzzle of 118 songs pieced together from a clandestine archival recording and extensive interviews with remaining members of the original Loft community.

Fusing the participatory and the historic, two additional FRONT commissions paired artists and musicians to establish a new shared language in sacred spaces. Cory Arcangel, who trained at Oberlin’s Conservatory of Music, co-opted carillons in downtown Cleveland churches with an algorithmic composition that generates daily scores made of emojis, numbers and symbols. Each church’s carillonneur could interpret the code as it rolled. The result, played simultaneously across the city at noon each day of the triennial, is a delightful chaos producing a dissociative state for anyone who encounters it.

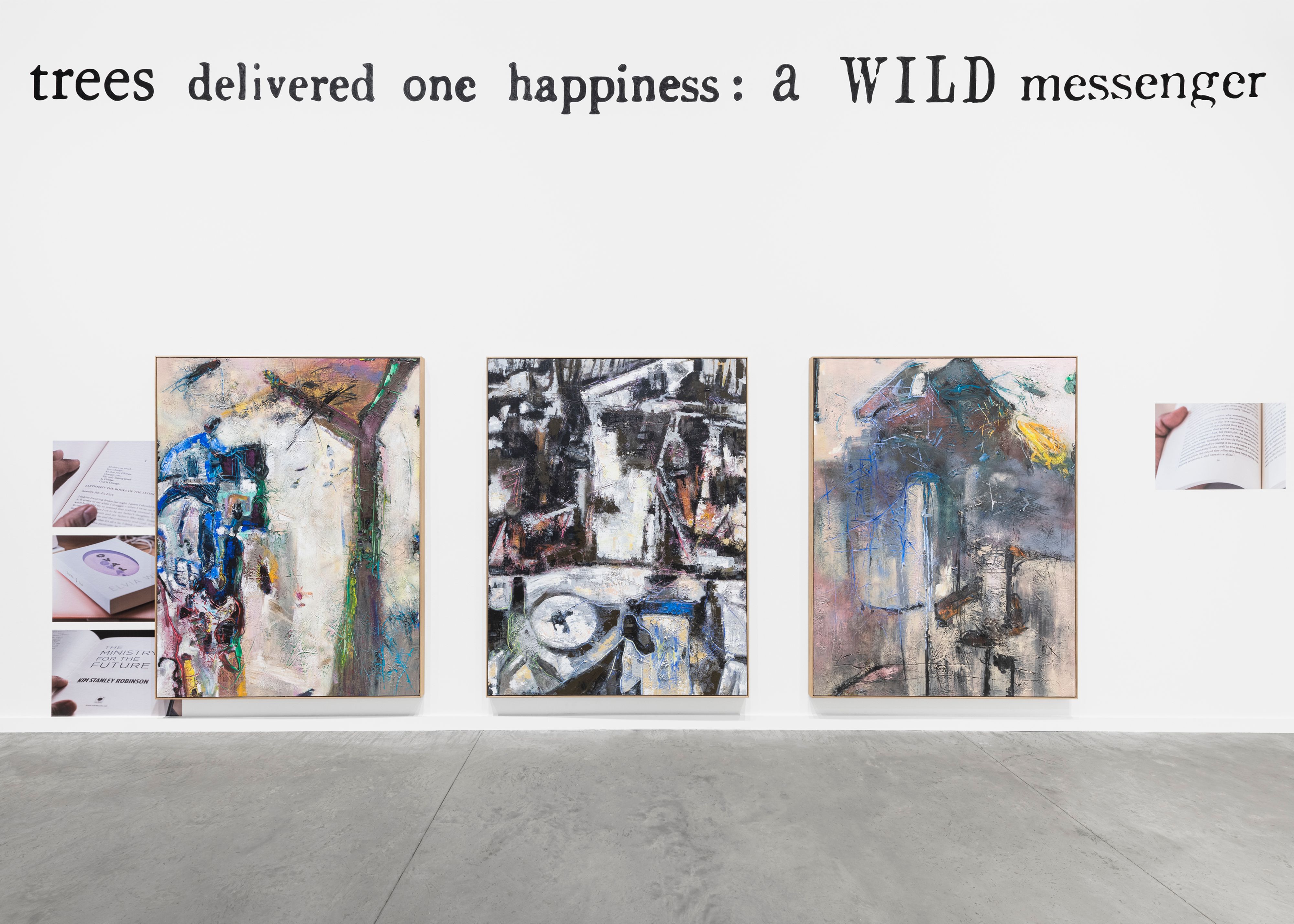

After Charles & Ray Eames, “What is design?,” 1969. Installation view, FRONT PNC Exhibition Hub at Transformer Station, July 16–October 2, 2022. Photo: Field Studio.

Berlin-based Asad Raza organized Delegation, a multi-part experience involving Raza and a band of Buckeye musicians sailing from his hometown of Buffalo, New York to Cleveland over Lake Erie, navigating the cosmic route while composing a song informed by Seneca oral traditions and the nautical landscape. Upon landing, Raza and the musicians processed to Cleveland’s Old Stone Church to perform the arrangement and teach it to passersby, giving it life beyond the organized encounter.

Our current global moment is a paranoid one, vibrating between the compulsion toward release en masse on dancefloors from Kyiv to Queens and the terror of exposure to biological and manmade weapons of mass destruction. Krishnamurthy’s FRONT mirrors this state of vulnerability best through these works predicated on the charms of music. They pull us, both actively and passively, into the awkwardness of improvisation with the promise, albeit a tenuous one, of harmony and resolution — an acknowledgement of what many people seem to be seeking from their contemporary encounters with art.