52 WALKER’S EBONY L. HAYNES IS SLOWING DOWN THE ART WORLD

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

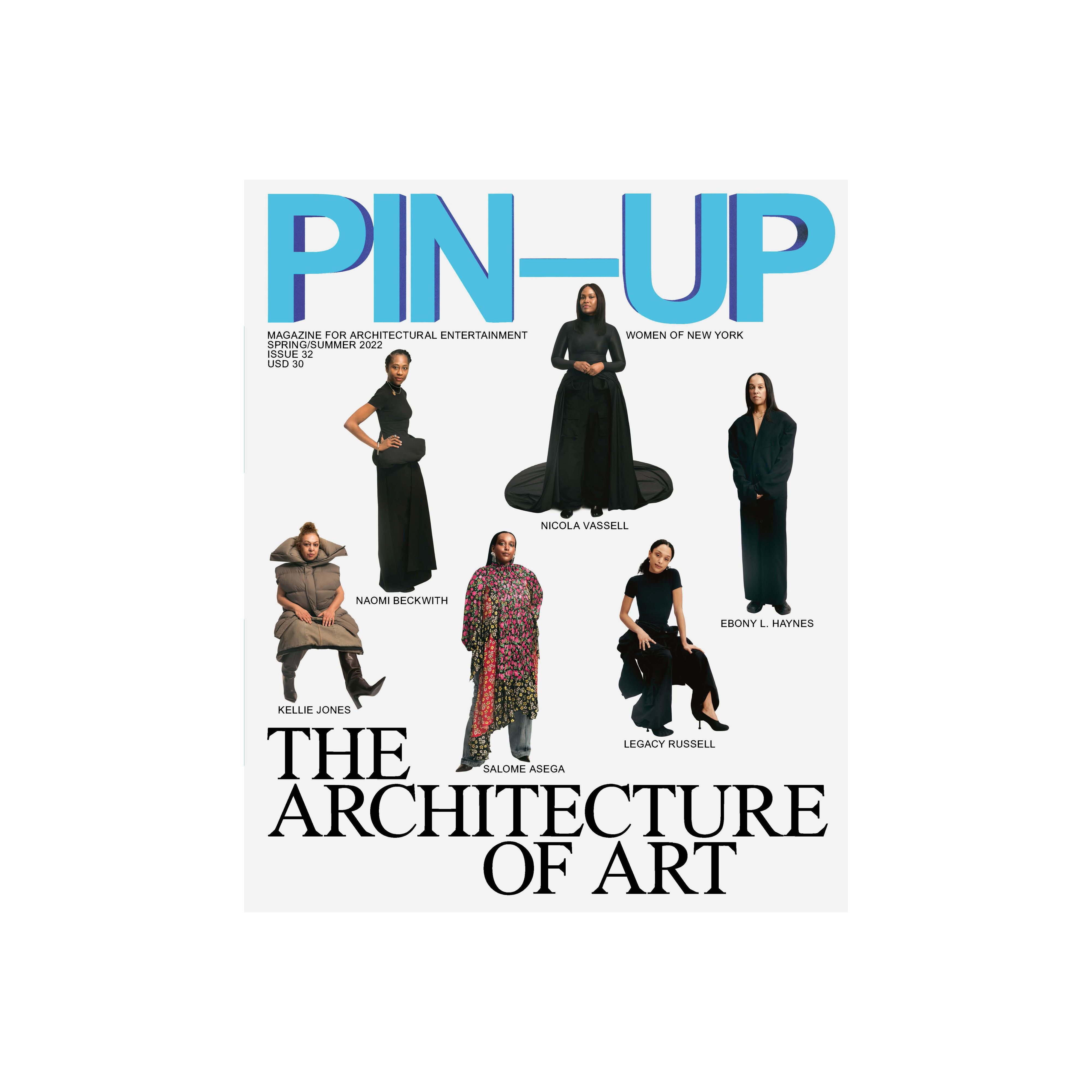

Ebony L. Haynes photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

Architecture wasn’t on Ebony L. Haynes’s mind when she first discussed her idea for a Kunsthalle with David Zwirner, but it’s come to shape her perception of 52 Walker’s programming. Departing from the traditional commercial-gallery format, this new Zwirner outpost, located at 52 Walker Street in Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood, will not represent the artists it exhibits (even though the works are for sale), seeking instead to encourage the public to sit at length with the art and critically engage with its ideas. After finding the space in the ground and lower floors of a five-story landmark building, Haynes, who was previously director of Martos Gallery and Shoot the Lobster, began to imagine how the recesses in the former kitchen could act as the ideal sites for readings and performances, and shared floor plans with the artists so that ideas would crystallize ahead of time. Very much an anomaly in the American art market, 52 Walker doesn’t pander to the zeitgeist but seeks instead to slow down the art world’s constant careening, programming fewer shows with a longer duration. Four exhibitions per year will be held in the Selldorf Architects-renovated space, each with its own publication. After debuting last fall with Kandis Williams (see PIN–UP 29), the gallery is following up this year with Nikita Gale, Nora Turato, Tiona Nekkia McClodden, and Tau Lewis. Looking to cast aside the art world’s tendency to mindlessly chew up and spit out narratives about gender, race, and identity, 52 Walker favors giving these ideas the space they deserve — and it’s one that Haynes built from the ground up.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What’s your relationship to architecture?

Ebony L. Haynes: I’m a novice in architecture. When I was conceptualizing 52 Walker, I heavily referenced the Breuer Building at 945 Madison Avenue. It starts with the exterior for me. I’m a fan of the Bauhaus movement. At the Breuer Building, there’s something about the play between really leaning into the institutional feel with the tiling of the floor, the desk design, and how the lighting is intrusive and fluorescent that I’m drawn to. I also enjoy navigating the elevators in the lobby — it makes the space feel more like a school. And then I just had such great experiences spending time with exhibitions there. When I first moved to New York, I would tour the building a lot with the headsets on, and it became one of the first new places that became familiar to me.

EO: What were your references for programming 52 Walker? It’s interesting you mention the feeling of a school, considering how you’ve launched a consistent catalogue-publishing schedule and have recently introduced a library.

EH: I wasn’t thinking about schools explicitly but about institutions with viewing experiences that encourage you to stay longer or return more than once over the course of the show. Which is why I wanted to work with a model where the shows would be up longer than the standard four-to-six-week window. I was thinking about the Kunsthalle Basel, and thinking ahead ten years from now to allow the exhibitions to define the vibe over time, which would require people to trust the process more. I wanted to slow down in every way, whether through books, exhibitions, or giving artists more time to build a show. I also love the WIELS building in Brussels — there’s something about it that’s intimate and directed, and the way they do programming there is inspiring. I’m interested in models that try to rethink ways of experiencing art and how artists make work. I like that we can really focus on one project at a time and develop it to the best of our ability. The library was always an idea, but I didn’t know how it would work. I knew there needed to be a system of lists, which is how the idea for the online catalogue on our website came about. It’s an annotated index that we will continuously update. Anyone who has ever participated in the space, in a program, or made a book with us will be credited on the website index. When thinking about the archiving system, a reference for me was the back of old school library books that log who checked the book out previously.

EO: Why did you commit to announcing your programming years in advance?

EH: It’s been advantageous to give people more time to absorb the program, those who may not have heard of the artists before or who might want to plan their trip to New York around something we’re doing. There’s nothing speculative about the shows I’m putting on. It’s not about leaning into a moment or working with artists who are getting a lot of buzz.

EO: How has that informed the way artists approach working in the space?

EH: Programming the space two years in advance — we’re scheduled from now through July 2024 — has been really freeing. There are a lot of concurrent conversations happening with different artists, which is really rewarding because there’s time to think, to visit, and to reflect on the space and how shows live in it before the artists make any decisions. It’s not traditional for a commercial gallery to give an artist a year’s notice to plan a show. I’ve worked mostly at smaller and mid-tier galleries, where there wasn’t much lead time and little of the infrastructural support I have here by existing within the larger Zwirner network. I have a long history with curating, and I wanted to program artists I’ve worked with in the past, but on a larger scale. I didn’t know how large the space would be, but it didn’t matter — I approached the artists before we secured the space. After we found the building, where possible I brought them by to see the space during demolition so we could start ideating very quickly. I shared the floor plans and designs with them so they knew how things were shaping up.

EO: How did you go about finding the building?

EH: I was mostly on the ground looking at various spaces with David Zwirner. There was nothing predetermined about where the space would be located. In one of my many visits to Tribeca, I noticed this space in a building had been closed due to COVID-19. We inquired about it, but it took some time to figure out the logistics. I didn’t think the space would shape how I approached what I was going to do program-wise.

EO: Really?

EH: I think it’s easy to see now how the space informs the shows, but I wasn’t considering it from the beginning — it was really a chicken and egg situation. David’s an architecture nerd and I was so surprised by how much he cared about every detail of developing the space during Selldorf Architects’ build-out and renovation. I think we both felt the potential here.

EO: How did you decide on Selldorf Architects?

EH: There’s a pre-existing relationship there with David — Annabelle Selldorf has designed most of the Zwirner art spaces. I didn’t want 52 Walker to feel like a huge departure from the history of Chelsea and the uptown galleries. I didn’t want the space to feel unserious. We have two stories, with more than 10,000 square feet of gallery space. Downstairs there are two large viewing rooms, office spaces, communal work areas, a kitchen, art storage, and 10-foot ceilings.

EO: How have people perceived 52 Walker so far?

EH: People think everything we’re showing is all-Black artist programming, which I don’t mind, but it’s not accurate. I’m not upset about how anyone would perceive the space because it’s very new, and while it isn’t a groundbreaking model for the art world writ large, it’s a new context for me to work in.

EO: How does 52 Walker translate to other cities? Would you franchise?

EH: That’s such an interesting question. I’ve never thought about it. I don’t think I would. The MoMA doesn’t exist in Los Angeles. Though it’s less about the city than it is the working model for the gallery.

EO: For you, what’s at stake for 52 Walker?

EH: [Laughs.] I think about Hal Foster when I hear that question.

EO: [Laughs.] He’s the reference point for this question. I was thinking about his 2015 book, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency, where he looks back over a quarter-century of art-making, trying to make sense of what happened after 1990. The book details the mechanics of the changing art world, serving as a how-to in terms of recognizing the different languages, movements, and systems that define us.

EH: Yeah, I’ll never forget when he came to a lecture when I was in graduate school. I had this inappropriate obsession from afar with October [the art, criticism, and theory journal of which Foster is a long-time editor] and Rosalind Krauss, and with him, but I only knew them as names. And then he came to do this talk. Apparently, he’d done this same talk before, but I had never seen it. But two people in the crowd specifically asked him, “What’s at stake for you?” And we ended up talking about what’s at stake for us personally and the importance of moving through these kinds of spaces and the work we do with that kind of intentionality. With 52 Walker, I’m trying to support artists and Black students interested in working in the art world by cultivating new community standards that don’t adhere to the status quo.

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.