Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

The swerves and curves of Douglas Cardinal’s flowing designs evoke ripple marks left in the sand at low tide, the gentle undulations of the prairie foothills, and the whorled arrangement of wildflower leaves. The 88-year-old identifies as a disciple of organic architecture, believing that buildings should be inspired by and blend in with their natural surroundings, an ethos that has long resonated with Cardinal because it’s aligned with the Indigenous values he was raised with. Cardinal was born in 1934 in Alberta, Canada, traditional lands of the Blackfoot people — his father’s ancestry was Blackfoot, Ojibwe, and French while his mother was German, French, and Mohawk/Métis. Cardinal’s experience as an architect has been shaped at both the personal and professional level by his perseverance against the Canadian government’s racist policies and settler-colonial culture. As a young man, he sought out Frank Lloyd Wright in Arizona before completing an architecture degree in Texas. After graduating, in 1963, he returned to Canada, where he went on to design some of the country’s most iconic buildings, among them St. Mary’s Church, Red Deer, Alberta (1968), and the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau, Quebec (1989), which earned him the prestigious Order of Canada. Fifteen years later, in 2004, he completed the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., while more recent work includes an indigenous-centered exhibition that represented Canada at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, and the 25-story residential tower Odea Montreal, currently under construction in partnership with the Cree Nation Government. Today, Cardinal is based in Ottawa, where his wife, Idoia Arana-Beobide, manages his studio with him.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Whitney Mallett: Let’s start by talking about your early life. You grew up with your family living off the land, hunting your own food, and those kinds of things?

Douglas Cardinal: My father left the reserve because it was controlled by the English people. They had an Indian agent [a representative of the Canadian government] on every reserve, and he decided he would just be independent of that craziness. His grandmother was a very powerful holy woman of the Blackfoot nation, and he’d learned everything from her about how he could survive and thrive by living off the land. Because of his knowledge of nature and wildlife, the government asked him to be a forest ranger, and then a fur, fish, and game inspector. If somebody killed a female deer with a fawn, my father would ask me to look after the motherless baby deer and bring it back to health. So I was always exposed to wild animals and saw what amazing, intelligent creatures they are.

When did you first become interested in architecture?

My father was always building. He built a log cabin in the Porcupine Hills where he and my mother moved after they got married. He was a good carpenter and handyman. If we needed a bed, he’d build it. I was always with him while he was building stuff, and I was always filled with questions. Why are we doing this? Why are we doing that? My mother said, “With all the questions you ask, I’m sure someday you’ll want to be a master builder or an architect.” My mother also wanted me to be trained in music because she said that was a way to create an art of the soul. She was the one who got me interested in the arts and reading.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Did you go to Catholic school?

Yes. My maternal grandmother was a very strong Catholic, but my mother ended up marrying my father, who was outside the church. He felt that Christianity was a lot of hogwash because it was a hierarchical system — you had to go through a priest who interprets your relationship with the creator. My father had been taught by his mother and his grandmother that everyone has a personal relationship to the creator. So my mother’s mother worried that, because her daughter was married to this heathen, her soul would go to hell and burn forever. Hell is pretty terrifying. That’s probably why so many people choose Christianity — because of fire insurance. [Laughs.] They advised my mother to put us children in a convent, not just a normal residential school, so we could learn to be good Catholics. When my two brothers and I went to the convent, they wouldn’t let us visit my mother for a year.

That must have been so traumatizing. How old were you?

Seven. By that age you’re already a relatively fully-formed human being, so I knew who I was. I questioned the church. Even as a child I could see right away that what they were trying to do was make us into British subjects. I would stand up and say there is no way God would do anything like that. Then I’d get punished. Eventually, I decided to do my best and I became the head altar boy. I learned the mass in Latin. I saw that the church had created beautiful art and architecture. I thought that the music was beautiful. I would play the piano all the time to deal with my problems, but I would still get stress attacks. At about 15 or so, I couldn’t deal with it anymore. I had tremendous anxiety, my body would go numb, and I would get terrible vertigo and throw up until I became unconscious. I asked my mother to forgive me, but I could not continue. So then I went to a public high school in Red Deer and got my matriculation to go to university.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Douglas Cardinal and Idoia Arana-Beobide, photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Next you went to Vancouver to study architecture, right?

Yes, I went to architecture school at the University of British Columbia, but I didn’t like the Bauhaus and early Corbu they taught. It was all very rigid and about man’s dominion over nature. I felt that the architects of the church made more sense — they were trying to capture the soul in their work. The only Modern architecture I felt was legitimate was the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, because he had a connection with nature. Later on, I met a Cherokee elder named Lloyd Kiva New who Frank Lloyd Wright learned a lot from. But I felt the Modern Movement was removed from nature in every way, including human nature. The only stuff I could relate to by Le Corbusier was his later work, Ronchamp and La Tourette. I thought, “Now that’s architecture.” It has a sense of spirit. He’s abandoned his precepts and he’s going with his gut. And I liked Rudolf Steiner: he was talking about the soul and caring about the environment and people. But I couldn’t identify with most Modernist architecture. And the school said the reason was that it takes a while for some people to become, you know, “civilized.” They said I did not have the right family background, and, because I was rebellious, they felt I was not “architecture material.”

Did you get kicked out?

I decided I should just forget about school and apprentice instead. I went back to Alberta and got hired as a draftsman by this architect Patrick Campbell-Hope, who was really British. He was designing all these schools. It was a factory churning out one after the other. I learned a lot from him, but there was no creativity. I wanted to go to Frank Lloyd Wright’s school, Taliesin West. So I pointed my car south and started driving until I got to Arizona. I ended up staying there for a little while. It was great to spend time with Frank Lloyd Wright and see what he was doing — he was working on the Mile-High tower at the time [the Mile-High Illinois, an unrealized project]. He liked my drawings, but I found out his school wasn’t accredited in Canada. I decided it didn’t make sense to go. While in Arizona, I got a job working for another architect and he recommended I go to his alma mater, the University of Texas. And so after taking a trip to Mexico, where I saw so much amazing architecture, I ended up in Austin. I started working for another architect who was also a professor at the university. It took me longer to get my degree because I had to earn my living while at school, so I was there for seven years.

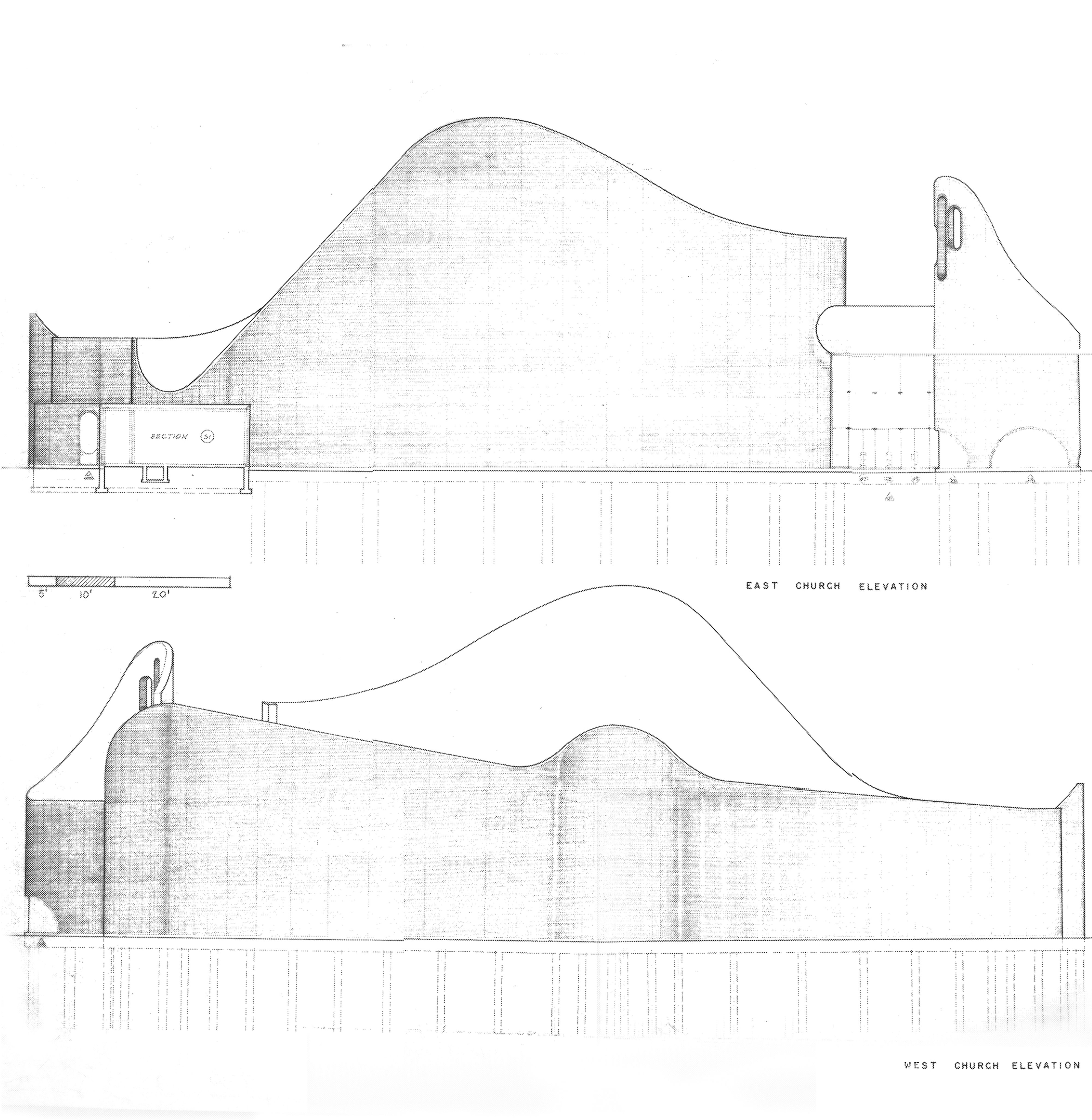

St. Mary’s Church, Red Deer, Alberta. Image courtesy Douglas Cardinal Architect.

You had a lot on your plate, studying and working at the same time.

And I was married, with a young baby. I had everything against me, but everything for me at the same time. I also got involved with the civil rights movement. The director of the school at that time was a racist. This was the 1950s. It was worse than what you saw on TV. They’d use shotguns and fire hoses against people. Some of my friends got killed. I saw the young folks taking over and rebelling against the old way of doing things. I stood for the integration of the school of architecture. And when it came to selecting a representative, the students wrote my name across the ballot. I realized one has a lot of power just by standing up and speaking the truth. Later I decided that I had to come home and deal with the crap I’d dealt with all my life. I mean, I was seeing all these great people sacrificing their lives. They were inspiring to me. And I just thought of the horrible racism and the crap that we have in this country, and how badly Native people are treated in Canada.

After you founded your own practice, in 1964, one of your first big projects was St. Mary’s Church in Red Deer. How did that come about?

I’d just started my firm, so I was renovating basements, building house extensions — whatever work I could get. You know those Butler buildings that are made out of steel, the package-deal warehouses where they sell tractors? Well, the Butler representative asked me to design the fronts of these buildings. He was a good Catholic, and he said, “Wouldn’t this design make a good church?” He happened to be the head of the building committee for the new church in Red Deer. So he introduced me to the priest, Father Merx. He was a well-educated guy from Germany. He knew all about architects like Rudolf Steiner, and he started telling me about how the pope had come up with a new liturgy — a more loving and caring document for the people. We talked about how the basilica form of churches came from the Roman judiciary plan, but with the new liturgy you could abandon the old basilica plan. I said, “Wouldn’t it be an adventure to design a church around the new liturgy?” And he said, “Yes, a church that goes back to the heart of Christianity, one that’s about loving and caring and respect for everyone — not this huge hierarchy.”

Consecrated in 1968 in Red Deer, Alberta, St. Mary’s Church cemented Cardinal’s early career. The architect was hired to abstract the recently modernized Catholic liturgy into an architectural form. For inspiration, he turned to Christian gatherings that predated the common cruciform churches. An oculus directs natural light to the altar and tabernacle, while the technologically innovative amorphous ceiling projects audio without the need for microphones. Cardinal continues to create designs for various spiritual centers and monuments of Indigenous and Christian faiths alike, such as the Iskotew Tunney’s Pasture Healing Centre in Ottawa and the Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall in Gatineau, Quebec. Image courtesy Douglas Cardinal Architect.

So together you came up with this really avant-garde organic-architecture design, based around the form of the circle. How did you get it approved?

I wasn’t Catholic anymore. Father Merx accepted the fact that I followed my traditions because they were based on loving and caring. But he said he was going to have to convince the archbishop. Now I had met Archbishop Jordan before. When I was around 21, I was beat up by a bunch of Catholic kids who were from very important families. This other priest wanted to protect those good Catholic families. They wanted me to go to jail for five years because I was a Native kid. I would get five years for being the one who was beat up — that’s how the system operates. So I went and spoke with the archbishop. I said, “This is wrong.” He said, “You’re darn right it’s wrong,” and he hired the best lawyer in Western Canada to defend me. Everything was dismissed. So, years later, when the archbishop saw me, he said, “Doug, what are you doing here?” I explained that I was Father Merx’s architect. He asked Father Merx, “Is this the only architect who can do your church for the new liturgy?” The priest said, “Yes.” And the archbishop said to me, “You did a good job. It’s nice to see you again under different circumstances.”

How did your complicated feelings towards Catholicism influence your experience working on the design of the church?

As difficult as it was, the important thing was to turn it into something good. I talked to an elder, and he said, “If you can create something that generates more loving and caring, a place where people can communicate with each other and with the spirit in a good way, then you’ve done your job. You might get criticized for it, but so what.” He was a tough elder. We had these rough sweat lodges. They were super hot. He’d say, “Choose: are you a victim or a warrior? Victims blame everybody else. Warriors take on full responsibility for their life.” That was the best thing I ever did, because before I was filled with anger and hatred, and after working with Father Merx and Archbishop Jordan, I didn’t have that anymore. How can you create when you’re filled with anger and hatred? You have to believe that there’s beauty inside you that’s worth expressing. You can’t do that filled with anger. That’s something the elders taught me.

Douglas Cardinal photographed by Yang Shi for PIN–UP.

Your architecture practice intersects with some important milestones in Indigenous sovereignty in Canada. How did you get involved with politics?

There was this government minister from Calgary, Fred Colborne. Because he loved my church, he’d given me work designing hospitals and other public works. He said, “Somehow you’ve been able to cut through all the bureaucracy on these projects, but I have a real challenge for you — I want you to help your people.” In 1969, Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s government put out the White Paper, which was going to wipe out Indigenous rights — all our traditions and history [the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, as the 1969 White Paper was also known, proposed to abolish all treaties and agreements with First Nations Peoples]. Because of my own health, I was working with the elders at the time and they asked me if I would help them put together their concept for the future. So I wrote down their vision for a school and I did my architectural design — and actually because they’re shamans, part of it they sent to me in a dream. Then Minister Colborne arranged for a delegation from Alberta to meet with Prime Minister Trudeau and his cabinet. I figured they were going to send the chiefs, but the chiefs said, “Doug, you speak good English and we have our accents. We want you to address them on their terms.” So they tied my long hair in braids and sent me to Ottawa. After I presented the vision for a school, there was silence for a while. Trudeau said, “One day I’m going to have children and I’d like to send them to a place like this.” After that he added Indigenous rights into the constitution. And they signed a document with all 52 chiefs in Alberta. But the Department of Indian Affairs came and intimidated the chiefs in Alberta. They made it impossible to implement the plan. But in the end what came out of it was the First Nations University of Canada in Saskatchewan. We were able to implement the first school on a reserve there. And once there was a school on one reserve in one province, there was a precedent to build them all across Canada.

Can you tell me more about the Cardinal studio and residence that you built in the early 1980s in Stony Plain, Alberta. It’s so gorgeous and sculptural.

Of course I wanted to have a studio built in nature. I’d visited houses that were built by our people in British Columbia, the pit-house dwellers. They built their houses deep in the ground, covered by earth. They were so well insulated, they were almost net-zero energy. Cuddling up together would create enough heat to survive the winter. So, I thought, why not build my studio in a hill and cover it with earth so I could protect it from the north winds. Then I had an all-glass front facing the sun. Even in the winter, it was pretty warm with the sun reflecting off the snow. I had trees inside and a pool. It was a fun place to live. I had my sweat lodge outside to maintain my health.

Cardinal Studio and Residence, Stony Plain, Alberta. Image courtesy Douglas Cardinal Architect.

In the mid-1980s you had to relocate from the prairies to Quebec to build the Canadian Museum of History, arguably your most famous and most monumental work. How did the commission come about?

What happened was photographs of all my buildings until then were exhibited as works of art in a gallery in British Columbia, and, because the show was popular, it went on to tour in Europe. External affairs heard about this international recognition and put me on a list of 80 architects to be considered for the national gallery and museum. I put everything I had into this competition. Trudeau had introduced this national energy policy that caused all the oil companies to leave Alberta and that was a real problem. Our economy went down and there was no work for architects. I thought I would be in deep trouble if I didn’t win, so I worked on the competition day and night. In the end Moshe Safdie was chosen to design the national gallery and I was chosen for the national museum. When it came time to announce the winners we flew to Ottawa, and as we were being ushered into the Prime Minister’s area, Trudeau said, “Where the hell is that Indian architect?” I had cut my hair and was wearing a three-piece suit, so he didn’t recognize me without my regalia. I said, “I haven’t changed. I’m the same in here. I’m just trying to respect the fact I’ve come to Ottawa.” He said, “Good. If you make the same commitment to me as you did to your people, I’ll have a good museum.” He shook my hand and that was that.

The Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, was a massive undertaking. Completed in 1989, the curvaceous building appears almost as two separate structures, its public and operational spaces divided across two wings. With the flowing forms and Tyndall limestone cladding, Cardinal sought to harmonize the building with both its urban and natural surroundings. Though certain elements, including the glass-faced grand hall or copper-roofed southern wing, were meant to evoke Ice Age geology, the museum was also one of the era’s most technologically advanced cultural institutions. In the 1990s Cardinal was commissioned to design a number of other cultural institutions, most prominently the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. (2004), whose curvilinear façade recalls the Canadian Museum of History’s cantilevered northern wing. Image courtesy Douglas Cardinal Architect.

You’ve had many more milestones since then. At the end of the day, what drives you and what’s most important to you?

For me, nature is the teacher. People’s fear of nature and the idea of having dominion over it has created a crisis on the planet. I saw even as a child how settler culture destroyed everything it touched. I like the teachings of our elders: they say we are loving and caring creatures, but sometimes we get sidetracked by our own ego and arrogance. But if we approach life in a more humble way, we don’t hurt the people around us. You have to remember you are a product of your ancestors. You are a grandparent of all the generations that will come after you. Everything you do affects the past, the present, and the future, so you have to be responsible.