99 NAMES OF GOD

THE MISBAHA AS A DESIGN OBJECT

by Ibrahim Kombarji

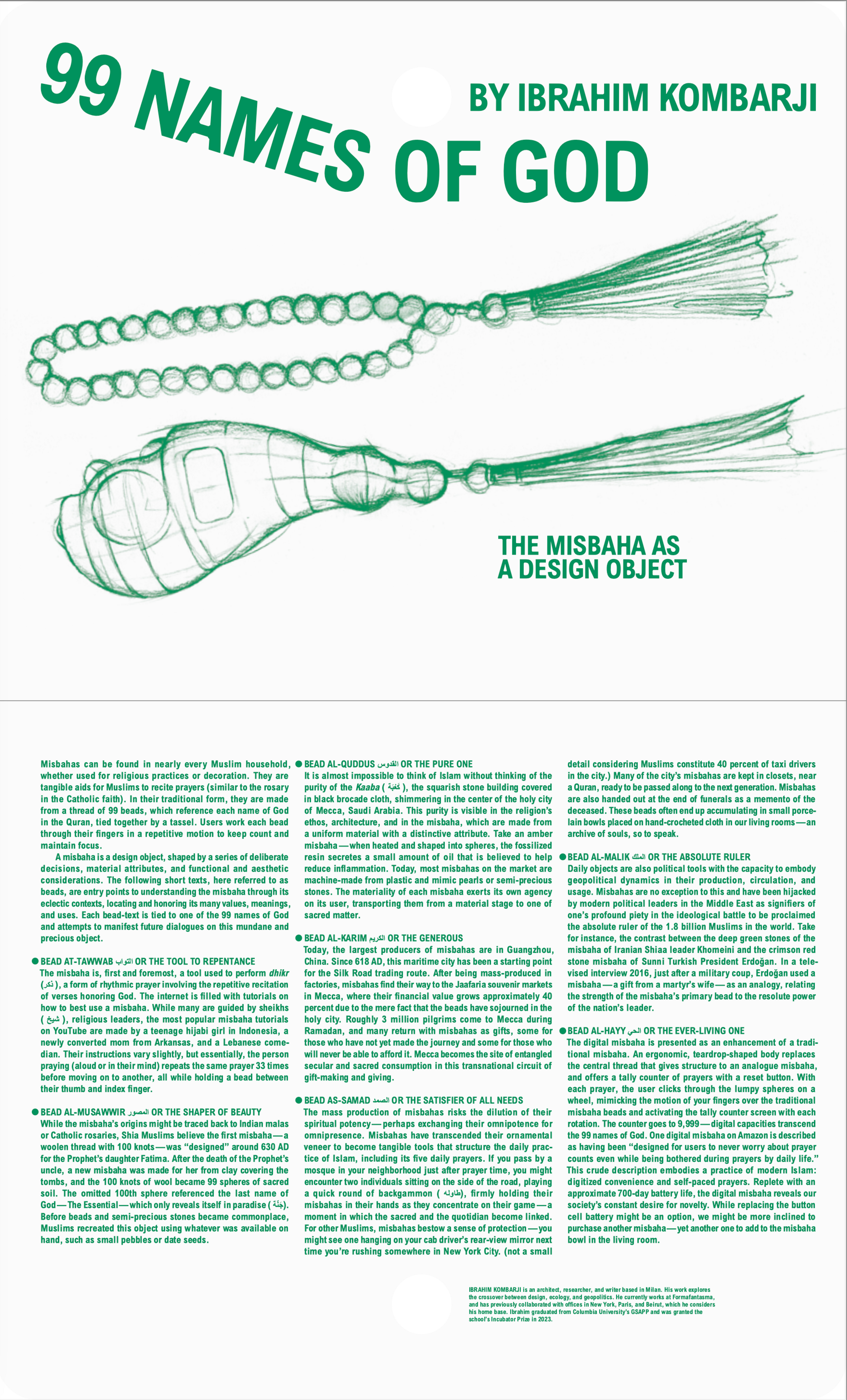

Misbahas illustrated by Raphael Ganz for PIN–UP and Nieuwe Insituut Design Drafts #2.

Misbahas can be found in nearly every Muslim household, whether used for religious practices or decoration. They are tangible aids for Muslims to recite prayers (similar to the rosary in the Catholic faith). In their traditional form, they are made from a thread of 99 beads, which reference each name of God in the Quran, tied together by a tassel. Users work each bead through their fingers in a repetitive motion to keep count and maintain focus.

A misbaha is a design object, shaped by a series of deliberate decisions, material attributes, and functional and aesthetic considerations. The following short texts, here referred to as beads, are entry points to understanding the misbaha through its eclectic contexts, locating and honoring its many values, meanings, and uses. Each bead-text is tied to one of the 99 names of God and attempts to manifest future dialogues on this mundane and precious object.

Bead At-Tawwab التواب or The Tool to Repentance

The misbaha is, first and foremost, a tool used to perform dhikr (ذکر), a form of rhythmic prayer involving the repetitive recitation of verses honoring God. The internet is filled with tutorials on how to best use a misbaha. While many are guided by sheikhs (شيخ), religious leaders, the most popular misbaha tutorials on YouTube are made by a teenage hijabi girl in Indonesia, a newly converted mom from Arkansas, and a Lebanese comedian. Their instructions vary slightly, but essentially, the person praying (aloud or in their mind) repeats the same prayer 33 times before moving on to another, all while holding a bead between their thumb and index finger.

Bead Al-Musawwir المصور or The Shaper of Beauty

While the misbaha’s origins might be traced back to Indian malas or Catholic rosaries, Shia Muslims believe the first misbaha — a woolen thread with 100 knots — was “designed” around 630 AD for the Prophet’s daughter Fatima. After the death of the Prophet’s uncle, a new misbaha was made for her from clay covering the tombs, and the 100 knots of wool became 99 spheres of sacred soil. The omitted 100th sphere referenced the last name of God — The Essential — which only reveals itself in paradise (ةّجن). Before beads and semi-precious stones became commonplace, Muslims recreated this object using whatever was available on hand, such as small pebbles or date seeds.

Bead Al-Quddus القدوس or The Pure One

It is almost impossible to think of Islam without thinking of the purity of the Kaaba (ةَعبْك), the squarishَ stone building covered in black brocade cloth, shimmering in the center of the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. This purity is visible in the religion’s ethos, architecture, and in the misbaha, which are made from a uniform material with a distinctive attribute. Take an amber misbaha — when heated and shaped into spheres, the fossilized resin secretes a small amount of oil that is believed to help reduce inflammation. Today, most misbahas on the market are machine-made from plastic and mimic pearls or semi-precious stones. The materiality of each misbaha exerts its own agency on its user, transporting them from a material stage to one of sacred matter.

Bead Al-Karim الكريم or The Generous

Today, the largest producers of misbahas are in Guangzhou, China. Since 618 AD, this maritime city has been a starting point for the Silk Road trading route. After being mass-produced in factories, misbahas find their way to the Jaafaria souvenir markets in Mecca, where their financial value grows approximately 40% due to the mere fact that the beads have sojourned in the holy city. Roughly three million pilgrims come to Mecca during Ramadan, and many return with misbahas as gifts, some for those who have not yet made the journey and some for those who will never be able to afford it. Mecca becomes the site of entangled secular and sacred consumption in this transnational circuit of gift-making and giving.

Bead As-Samad الصمد or The Satisfier of All Needs

The mass production of misbahas risks the dilution of their spiritual potency — perhaps exchanging their omnipotence for omnipresence. Misbahas have transcended their ornamental veneer to become tangible tools that structure the daily practices of Islamic life, including its five daily prayers. If you pass by a mosque in your neighborhood just after prayer time, you might encounter two individuals sitting on the side of the road, playing a quick round of backgammon (طاوله), firmly holding their misbahas in their hands as they concentrate on their game — a moment in which the sacred and the quotidian become linked. For other Muslims, misbahas bestow a sense of protection — you might see one hanging on your cab driver’s rear-view mirror next time you’re rushing somewhere in New York City. Many of the city’s misbahas are kept in closets, near a Quran, ready to be passed along to the next generation. Misbahas are also handed out at the end of funerals as a memento of the deceased. These beads often end up accumulating in small porcelain bowls placed on hand-crocheted cloth in our living rooms — an archive of souls, so to speak.

Bead Al-Malik الملك or The Absolute Ruler

Objects are also political tools with the capacity to embody geopolitical dynamics in their production, circulation, and usage. Misbahas are no exception to this, having been hijacked by modern political leaders in the Middle East as signifiers of one’s piety in the ideological battle to be the absolute ruler of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims — observe the contrast between the deep-green stones of the Iranian Shia leader Ruhollah Khomeini’s misbaha and the crimson stone one of Sunni Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In a televised interview in 2016, just after a military coup, Erdoğan used a misbaha — a gift from a martyr’s wife — as an analogy, relating the strength of the misbaha’s primary bead to the resolute power of the nation’s leader.

Bead Al-Hayy الحي or The Ever Living One

The digital misbaha is presented as an enhancement of a traditional misbaha. An ergonomic, teardrop–shaped body replaces the central thread that gives structure to an analogue misbaha, and offers a tally counter of prayers with a reset button. With each prayer, the user clicks through the lumpy spheres on a wheel, mimicking the motion of your fingers over the traditional misbaha beads and activating the tally counter screen with each rotation. The counter goes to 9,999 — digital capacities transcend the 99 names of God. One digital misbaha on Amazon is described as having been “designed for users to never worry about prayer counts even while being bothered during prayers by daily life.” This crude description embodies a practice of modern Islam: digitized convenience and self-paced prayers. Replete with an approximate 700-day battery life, the digital misbaha reveals our society’s constant desire for novelty. While replacing the button cell battery might be an option, we might be more inclined to purchase another misbaha — yet another one to add to the misbaha bowl in the living room.

Design Drafts in PIN–UP 35.