Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

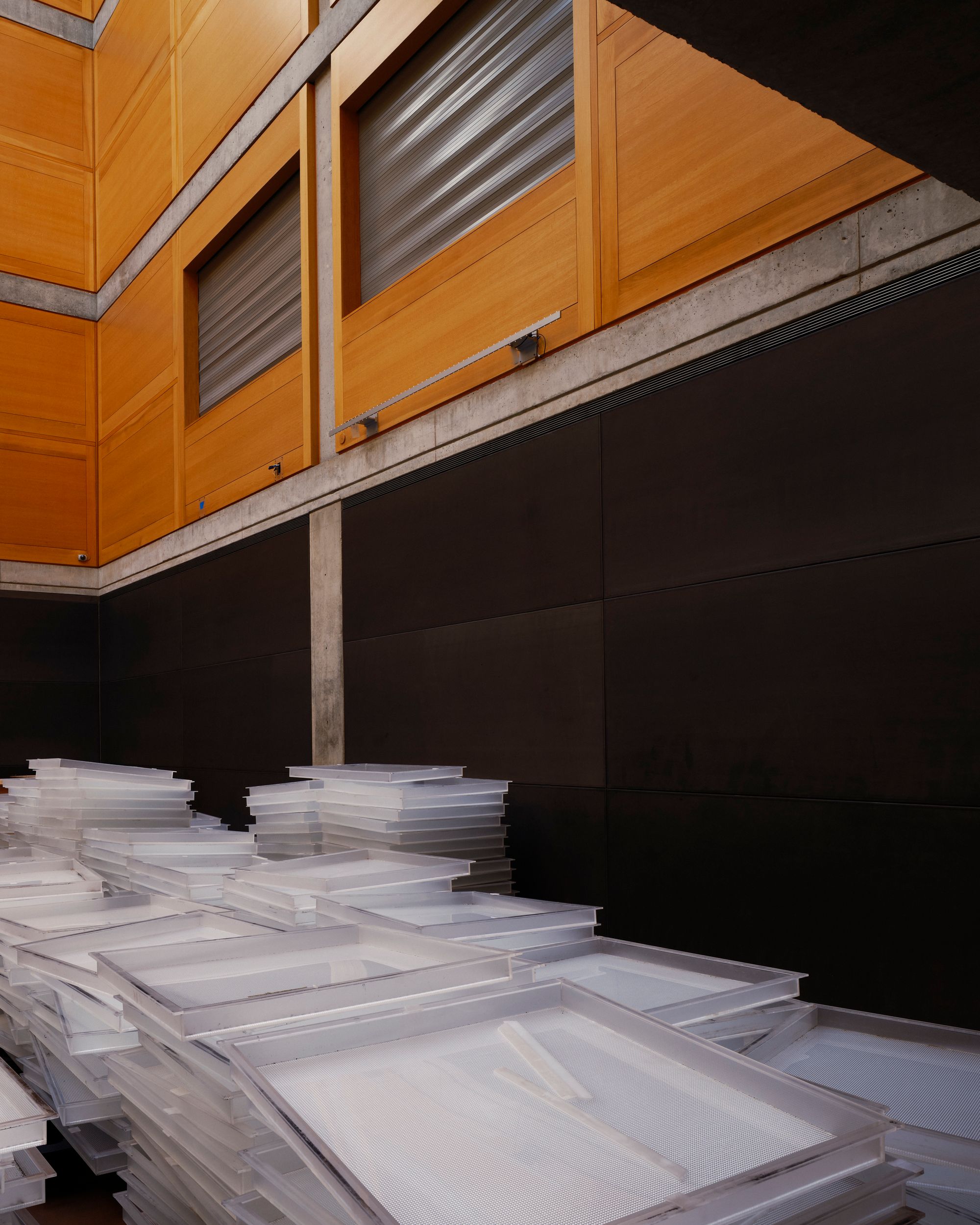

Courtney J. Martin, outgoing director of the Yale Center for British Art and incoming director of The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, stands amid one of her proudest achievements during her five-year directorship at the YCBA: the completion of a multi-year preservation project of the Louis Kahn building from 1977. Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

It was Valentine’s Day when I met Courtney J. Martin, but the director (since 2019) of New Haven’s Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) was not thinking about flowers and candy hearts. In addition to having had to struggle through unshoveled snowy sidewalks to reach her office, she had just been named the next executive director of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in New York. Even as she prepares to assume her new post late this summer, Martin faces a pile of responsibilities in New Haven, among which is finalizing an exhibition on J.M.W. Turner that will début in 2025 to mark the painter’s 250th birthday. All the while, the YCBA is effectively homeless, the landmark Louis Kahn-designed building on Chapel Street (1969–77) having closed for renovations in February of last year, an overhaul long sought by Martin and set to wrap up just as she heads out the door. To no small degree, the project represents the culmination of Martin’s curatorship at New Haven. Since her arrival, when she was reported to have read nearly every biographical and critical work in the Kahn canon, she has absorbed the late architect into her curatorial thinking, to the point where the building becomes not just a container but an object of contemplation, a work in its own right alongside the Constables and the Reynolds. Martin took time out of her demanding schedule to talk to PIN–UP about the relationship between architecture, art, and history, as well as the YCBA’s challenging acoustics.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Ian Volner: Do you remember the first time you saw Kahn’s YCBA building?

Courtney J. Martin: The first time I really looked at it was in the winter of 2000. It had snowed then, too, and I had come to have a conversation with a professor here about entering the graduate school. I remember seeing the YCBA and being struck by the combination of that building and the old art gallery [whose extension, completed in 1953, was Kahn’s first major commission], which housed the art-history department, sitting directly across the street. And I thought, “Those are the things that I want more than anything” — I had always wanted to be an art historian, and to study British art specifically. Because of the snow, the person I was going to meet did not show up, so I did the thing that I still do now whenever I have a chance, which is to go into the YCBA, right to the J.M.W. Turner bay, where his painting of the Dordrecht packet boat is displayed. From there, you can look out across Chapel and see the whole world go by. It is a great window.

So here’s this space you already admired so much, which years later you were put in charge of it. What has that been like?

It has been a huge responsibility to be at the helm of a landmark. No one gives you a guide or a blueprint. What does it even entail? And to what audience must you respond? Any museum is responsible for its structure, obviously — making sure people are safe, secure, that the building is accessible. But when you put the landmark feature on top of it, and the history of Kahn on top of that, it just amplified what my role had to be. It meant having to understand the principles that Kahn believed in, which were very different from that of any other architect. The building is even different from his other buildings. Kahn really did understand how to design buildings for the display of art, which is very much a niche field. And I do think that being the custodian of something like that has been really special. It forced me to grow, to learn.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

In the years that you’ve been leading the institution, how has the building influenced what you exhibit and the way you exhibit it?

I think the single best thing I have done was the Bridget Riley exhibition in 2022, Perceptual Abstraction. As an artist she is just so smart — focused, knows everything about her work. She can tell you all about the history of art and architecture, her relationships to those things. I had wanted to do a show with her for a long time, and my entry point into a deeper conversation with her was sparked by talking about this building. We began to discuss what a space like this could mean for her. The show we organized, with her leading us, was all about finding ways to allow both her smaller and larger pieces to be seen to good effect within the strictures imposed by the building. We gave her two floors (the museum had never done that with a living artist before) and, with the galleries arrayed around the building’s central column bank, it felt as though the work was really responding to the ethos of the architecture. It made sense in a way, because the building’s design dates back to the late 60s, around the time Riley started, and it was completed in 1977, after Kahn’s death, as her practice was growing and developing. Together, they just sang.

Still, there must be some things about the building you don’t like.

The acoustics. You can hear everything, every phone, raised voice, and whistle, as well as all the outside sounds when the door is open. There is not a space in the building that does not echo: it is all concrete and travertine, hard surfaces. Sound simply bounces around as you walk through the interior. The concrete makes you think you are in this stable fortress where no sound can penetrate, but actually it is totally porous. I can hear everything on every floor. You have to get used to it. It took me a long time, and I still do find it a little uncomfortable when I am talking — unless, of course, I am especially comfortable with the subject of the conversation.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

The acoustics, and the materiality, are pretty much permanent features of the building. What did you set out to fix with the current renovation?

The last renovation dates back to 2016, but as in any such project there were things that could not be done at the time. The reality of being a public-service institution is that we have to serve multiple audiences: New Haven residents; Yale students; researchers; the wider world; Kahn aficionados. Each renovation has to focus on a couple of those audiences, and in this one we wanted to do things that would be practical for exhibition purposes, but also necessary from an architectural perspective. I keep telling people, the best payoff for us will be if we can get a Norman Foster or a David Chipperfield to walk in here and say, “It’s perfect! It looks exactly like it did in 1977!” So we are now in the process of replacing more than 224 plexiglass skylights with polycarbonate, as well as changing the lighting tracks from halogen to LED. In all of this we have spent a lot of time talking to architects, in particular Deborah Berke, who is on our advisory committee. It was essential, we felt, for architects to be involved. This is Kahn’s masterpiece, and we wanted to do it right.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Naturally you did your homework on Kahn before you launched into the work. What did you discover about the building’s design process or about him?

One fascinating aspect was Kahn’s relationship with Paul Mellon, the YCBA’s founder. The building’s success came about because Mellon was prepared to let Kahn do what he wanted. And Kahn was very aware of Mellon’s collection, having been to see it in Virginia. He knew the works that would be displayed, and designed specific spaces for specific objects, where they and they alone can be placed. It was all part of Kahn’s original plan — and though his very American sensibilities might be unusual for a museum of British art, his client was half British, and their connection made it work. Mellon was never uncomfortable working closely with architects — he had a good relationship with I.M. Pei, for example, and he enjoyed giving power to his collaborators. He chose Kahn, and not by accident, so he knew what he was getting into when he made that choice. Kahn’s earlier project, the art gallery, is directly across the street. Mellon could see every day what Kahn might do. I do not think he was surprised by the result.

And now you’re preparing to move on to the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (which, incidentally, just finished a renovation). What are your plans once you get there?

There are so many things I do not know, which is super exciting. I do not know enough about Bob as a person. Given my own training, I know about his art, but why was he so interested in social justice? We can assume, but we do not know. Why did he decide to move to Captiva, in Florida, which was such a catalyst for his own thinking about the foundation. I do not even really know enough about artist-endowed foundations in general — I have some core knowledge, since I sit on the boards of both the Chinati and the Henry Moore Foundations, but the Rauschenberg is a very different place. I need to talk to as many people as possible. This is also New York City. I moved there right after college, and I find it endlessly fascinating, but I do not feel I know enough about the particular community around the foundation, the Nolita neighborhood, and its history and people. It is a lot to figure out, but it will happen. That is the job.