Mathieu Pernot, photographs from the series Les Gorgans [The Gorgans], 12th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 1995–2015. © Mathieu Pernot / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Photo by Silke Briel.

Photo of TK installation. Courtesy of TK.

In the curatorial statement for Still Present!, the 12th Berlin Biennale, French artist and this edition’s curator, Kader Attia, invokes his artistic research into repair as a guiding theme. Attia invited a team of contributors to “look back on more than two decades of decolonial engagement” and enter into “a critical conversation in order to find ways together to care for the now.” While art exhibitions famously ask more questions than provide answers, working through a mode of repair suggests an action will be taken — that strategies for “caring about the now” might be proposed, or at least a mediation of past knowledge within a present context. Unfortunately, by and large this was not the case. Instead, as Rahel Aima points out in her review for Frieze, the exhibition is “fragmented and dry-mouthedly rote: dutiful massaging of the colonial archive.” To engage in a conversation of repair, is a reference to colonialism enough? What can we expect and need from the constant flow of biennales today? Like Aima, I was also “left wondering who, precisely, this is for,” and what is the role of the artist versus curator in determining this?

Mathieu Pernot, photographs from the series Les Gorgans [The Gorgans], 12th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 1995–2015. © Mathieu Pernot / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Photo by Silke Briel.

Etinosa Yvonne, photographs from the series It’s All In My Head, 12th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2019–20. Photo by Silke Briel.

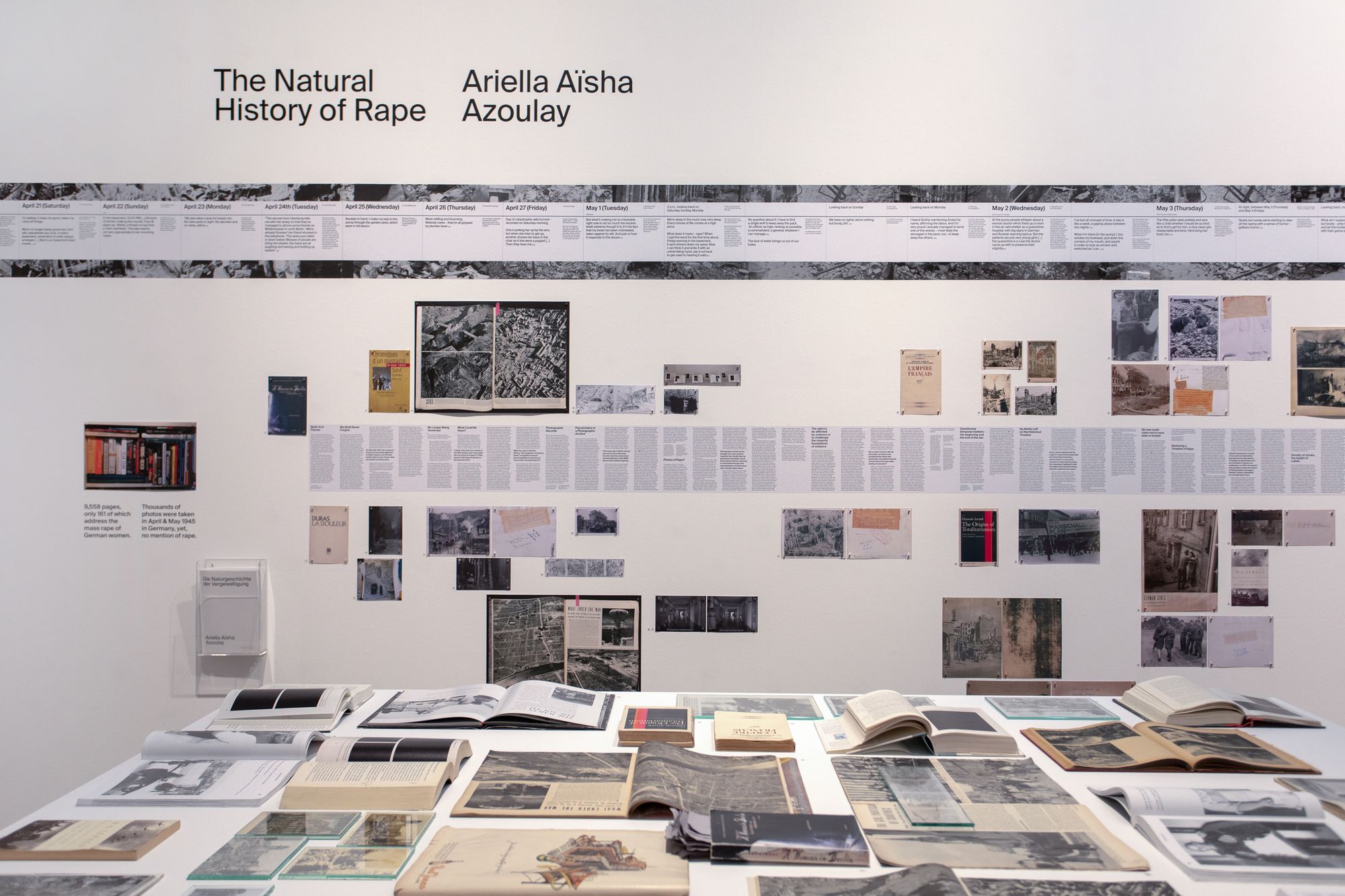

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Natural History of Rape, 12th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2017/22; vintage photographs, prints, untaken b/w photographs, books, essays, magazines, drawings. Photo by Silke Briel.

Overall, the main approaches taken to investigate, or rather testify to, colonialism were photographic reference and historical documentation. Among the selection presented at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art was heavy emphasis on photography, featuring Mathieu Pernot’s chronicles of the Gorgans, a Roma family living on the outskirts of Arles; Etinosa Yvonne’s portraits and alongside textual statements of female victims of sexual violence during armed conflict in rural northeast Nigeria; Nil Yalter, Judy Blum and Nicole Croiset’s presentation of a testimony by a former female convict in a French prison; Zuzanna Hertzberg’s “herstories of Jewish activism since the early twentieth century”; and Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s photo wall and timeline, The Natural History of Rape (2017–22).

Forensic Architecture, Cloud Studies, 2022, 12th Berlin Biennale, Akademie der Künste, Hanseatenweg; two-channel video installation, color, sound. Photo by dotgain.info.

At the Akademie der Künste, Hanseatenweg, the presentations were data-heavy, providing direct information with seldom poetic intervention. In one corner were works by Forensic Architecture (FA), a research agency, FA collaborator Susan Schuppli, Imani Jacqueline Brown, and Dana Levy, address environmental racism and access to resources (or lack thereof) in different regions. They mapped the trajectories of toxic clouds, the temperature weaponization against indigenous communities in Canada, Black Americans who live in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” and the degradation of occupied Palestinian land. Altogether, the approach felt more ethnographic than artistic.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, Oh Shining Star Testify, 2019/22, 12th Berlin Biennale Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart; three-chanel video installation, two-channel sound, subwoofer, 10 feet x 05 inches; wooden boards. Photo by Laura Fiorio.

Mónica de Miranda, Path to the Stars, 2022, 12th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art; video, color, sound, 34’ x 41”. Photo by Silke Briel

However, some of the video works stood out, weaving personal histories and cultural fictions into the traumas of imperialism and occupation. These include Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s meditation on the relationship between ecology and the legacies of French and Chinese colonialism in Vietnam, as narrated by the last Javan rhinoceros and a fifteenth-century sacred turtle; Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s multi-channel video installation that uses CCTV footage overlaid with tonal manipulations to recount the murder of 14-year-old Yusef Al-Shawamreh by Israeli forces; Mónica de Miranda’s poetic investigation into the women who fought for Angolan independence; and Clément Cogitore’s reinterpretation the 18th-century ballet-opera Les Indes galantes as a krump battle. Yet even the presentation of these noteworthy pieces was served cold with little scenographic imagination for engaging the public. If an exhibition includes video work or long texts, it should include adequate seating and a font size that is legible.

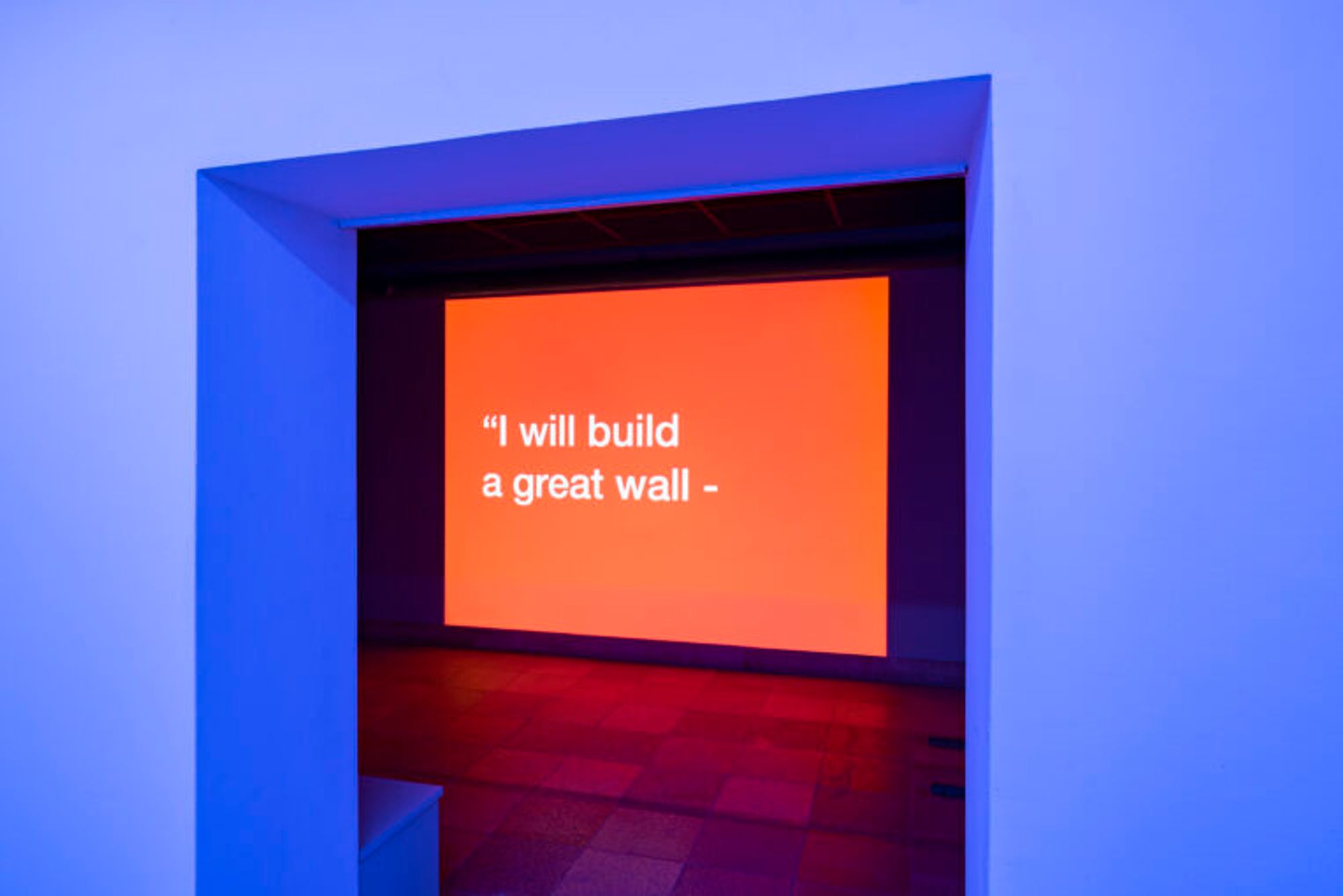

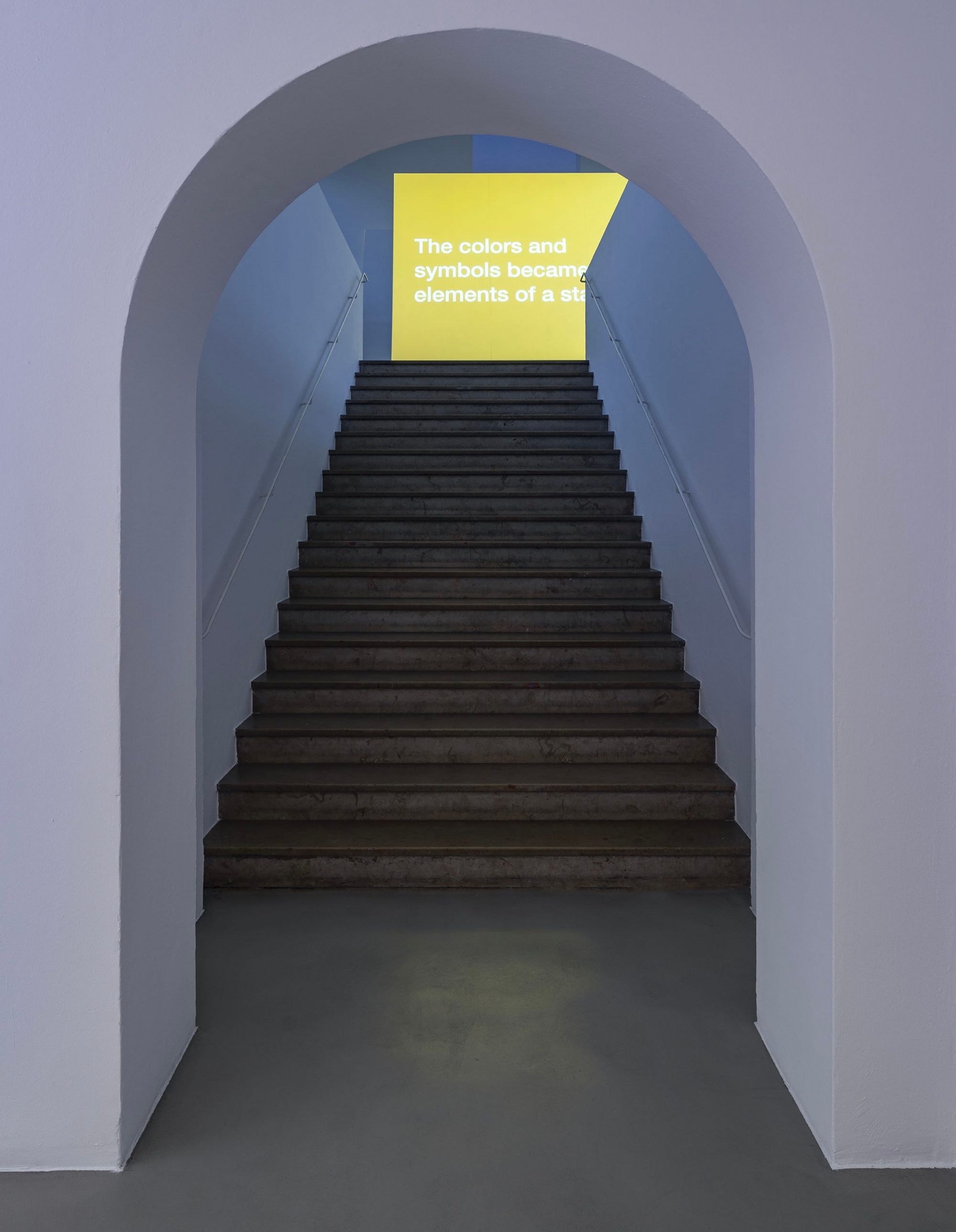

Where the Biennale, in Aima’s words, felt like “dining on sawdust,” Tony Cokes’s double presentation across the Haus der Kunst and Kunstverein München left me feeling marvelously full. Fragments, or just Moments, the American artist’s first institutional solo exhibition in Germany surveys his thirty-year oeuvre. In a style that the curators note, “radically rejects representative imagery,” Cokes pulls text from political speeches, music journalism, interviews, critical theory, and other found sources, setting his single-channel video essays against colored backgrounds and a soundtrack of pop, rock, and house music. The approach speaks directly to socio-cultural issues of capitalism, gentrification, racism, and warfare without replicating images of violence and its victims.

In Evil.16 (Torture.Musik) (2009/11) Cokes outlines how music was instrumentalized as a form of sonic torture for interrogations by US soldiers during the Iraq War, representing American cultural export violently weaponized. Where Cokes investigates nuanced layers of witness and complicity, Jean-Jacques Lebel’s Solvable Poison (2013), presented at the Hamburger Banhof as part of the Berlin Biennale, presents violent images of members of the US military torturing prisoners and posing them in sexually suggestive positions at Abu Ghraib prison near Baghdad. Part of a labyrinthine installation of color snapshots interspersed with black-and-white press images of destroyed Iraqi towns, this represents the worst of photo testimony as art. In the accompanying text, Lebel states that “the aim of this project is to provoke the viewer to meditate on the consequences of colonialism,” though beyond the potential for re-victimization, I am left wondering who this imagined viewer is.

In a cruel curatorial move, the Biennale team placed Lebel’s work near the young Iraqi artist Layth Kareem’s video The City Limits (2014). Here, Kareem gathers friends, artists, family members and neighbors in a junkyard that was the site of a car bombing in 2006. The accompanying text speaks of Kareem providing his community with space to “respond to the images and experiences suffered in daily life” and through their testimony transform them from “victims of circumstance into agents of their own emotional expression.” Where Kareem places himself and his community directly in the work, in a testament to gathering as a form of resistance, Lebel coldly blows up an act of violence, a form of execution whose only mode seems to be shock. While a juxtaposition of a western versus Iraqi artist’s perspective on the wake of war in Iraq could suggest these works should be in proximity, a priority of voice, especially in an exhibition that strives for decolonialism, seems misguided given the physically much larger space afforded to the French Lebel.

Since first writing this during the press opening in June, Iraqi writer and arts organizer Rijin Sahakian, published a letter (July 29) in Artforum co-signed by fifteen artists demanding the removal of this work, noting that they “stand firmly against this unconsidered reproduction of the invader’s crimes. She elaborates that “we, and every Iraqi we met who saw the work in question, were deeply disturbed, and felt betrayed by this inclusion… [as a] devaluation of… lived Iraqi experience.” The Biennale team’s response nearly a month later justified the continued inclusion as being “important not to indulge the impulse to turn a blind eye to a very recent imperialist crime…” as “repair and injury are inherent to each other: Showing one’s wounds is part of the process of exposing — and repairing — the crimes that human beings have perpetrated on others.” The following day, Sahakian, with 400 signatures of support, declared their withdrawal from the Biennale.

In the days between these exchanges I was reminded of a text that Paul Preciado wrote while participating in the Silent University in Athens in 2016 while working as the Director of Public Programs for Documenta 14. He asked, “how is the image produced and spread? Why has nobody seen any of the victims of September 11 while the massacred bodies of Aleppo make newspaper headlines?” For this discussion, I’m less interested in who has the right to make an image as I am in the posturing of what making or showing that sort of image signals. For the Biennale team to recycle an image of violence, under the guise of repair, seemingly without consideration for who this repair is directed at, seems dissonant with the curatorial mission. What is being decolonized here, and as a strategy to what ends?

Tony Cokes, Evil.66.2 (DT.sketch.2.7), 2016, part of Tony Cokes: Fragments, or just Moments at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2022. Courtesy of the artist, Haus der Kunst, and Kunstverein München. Photo by Max Geuter.

Tony Cokes, Some Munich Moments, 1937–1972, part of Tony Cokes: Fragments, or just Moments at Kunstverein München, 2022. Courtesy of the artist, Kunstverein München, and Haus der Kunst. Photo by Max Geuter.

The work of Tony Cokes proves that visual allure does not have to be divorced from conceptual rigor and political engagement. The relationship between color and form, text and background, and his keen use of repetition pulls viewers in without relying on shock tactics. The centerpiece of Cokes’s exhibition, Some Munich Moments 1937–1972 (2022) investigates the legacies of Nazi-era propaganda and aesthetic efforts towards de-Nazification on German national identity. Through a multi-channel layering of archival material, Cokes explores the Haus der Kunst (formerly “Haus der Deutschen Kunst”), home of the first iteration of the “Great German Art Exhibition,” which promoted art of Nazi aesthetics, and the Hofgarten building, which since the 1950s has housed the Kunstverein München and was the site of the Degenerate Art exhibition, which the Nazis famously staged as a counterpart. Cokes’s newfound use of representative imagery of Munich is non-figurative, displaying awareness of architecture and urbanspace within Nazi Aesthetics.

In sweeping shots of the Munich landscape, Cokes links the Nazi aesthetic strategy promoting their cultural ethics with the German visual attempt to signal a denazification and “cosmopolitanism” during the 1972 Munich Olympics. In the video, a text explains that the guideline for the Games was to shift the ideological alliance between fascism and sport and promote a new Germany. Moreover, the “apolitical” design of the new Olympic Stadium, created by graphic designer Otl Aicher, signaled a “celebration of peace.” It attempted to serve as an antithesis to the previous Games hosted during the Nazi rule.

Documenta, the notorious quinquennial exhibition, first organized in 1955 by Arnold Bode, was culturally signaling for this “celebration of peace.” Bode chose Kassel for its central location in Germany and unifying potential in a continent devastated by war. The first iteration also presented work by avant-garde artists banned by the Nazi regime, contemporaries and successors of those included in the Kunstverein München’s degenerate art exhibition discussed earlier. Today, as much as Documenta is an art exhibition, it is also a symbol of the reconfiguration of post-war German culture, one that considers itself the moral center of Europe. The dissonance between this view and a nuanced reality became a central issue of this year’s Documenta 15, raising a larger question of who Documenta is for.

Left to right: ruangrupa’s members: Daniella Fitria Praptono, Julia Sarisetiati, Ade Darmawan, farid rakun, Iswanto Hartono, Mirwan Andan, Reza Afisina, Indra Ameng, Oomleo (Narpati Awangga), and Ajeng Nurul Aini, 2020. Photo by Saleh Husein and L-R.

Workshop with ruangrupa, artistic team, and lumbung members at Documenta Fifteen, Kassel, 2020. Photo by Nicolas Wefers.

Directed by the Jakarta-based artists’ collective ruangrupa, Documenta 15 took a rhizomatic approach – ruangrupa invited fourteen other collectives to participate and invite their own communities to engage with the project. Here, they followed the values of lumbung, or “rice barn,” a communal building in rural Indonesia where a local region’s harvest is distributed collectively. They interpreted this over 100 days of programming, which included a greenhouse, a communal kitchen, an indoor skate park, video works, live performances, and workshops.

In his review of Documenta, ArtReview editor J.J. Charlesworth described ruangrupa’s curation as a “significant upending of the exhibition’s seven-decades-long run of appointing artistic directors who have always been professional curators, and (with the exception of Okwui Enwezor in 2002) all of them Europeans.” It dislocates a central idea stemming from a sole creator. The organizational structure suggested a striving for decoloniality, though that language was not used in the mission. With a focus on non-western collectives and working practices, the exhibition was located outside of the ideological confines of central Europe in terms of subject matter and artistic aesthetics.

This led to new narratives in projects such as Wakaliga Uganda, a film studio operating out of a slum in Kampala and producing low-budget yet extremely enthralling action films; Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s installation which links the history of torture at its exhibition site, the Rondell, with life in detention camps in northern Vietnam from the 1960s through the 70s as told through Bùi Ngọc Tấn’s auto-biographical novel Tale Told in the Year 2000; The Moana Oceanic arts collective FAFSWAG’s interactive installation which uses ballroom culture to create connections across the Moana diaspora; and Saodat Ismailova’s sprawling labyrinthe which tells the story of chilltan, or shapeshifters in Central Asian cultures.

However, this decentralized approach and a seeming disconnect between the Documenta board and ruangrupa resulted in controversial oversights. In the weeks leading up to the public opening, several claims of antisemitism were raised against ruangrupa, largely for their inclusion of Palestinian artists and collectives who might support the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel. Of central critique was The Question of Funding, a Palestinian collective whose research traces how foreign funding accessed by NGOs are redistributed and Eltiqa, the Gaza-based artist collective they were hosting. The central issue was if this collective’s inclusion was at odds with a 2019 Bundestag resolution that equated the BDS movement with anti-Semitism, and therefore made the support of it illegal in Germany — an issue for an exhibition funded by the German government.

In response, the German media attacked the collective in a manner that read as xenophobic and without consideration for sources. Against the backdrop of this media frenzy, the collective’s space was vandalized with “187,” the Californian penal code for murder, likely as a threat. Many members of The Question of Funding collective left Kassel and they canceled all public programming. Who is responsible for their protection? Ruangrupa? The Documenta board? The host collective? In a deeply hierarchical art world, was the Documenta board prepared to host such an un-hierarchical project?

These controversies became more complex with the reveal of Indonesian art collective Taring Padi’s political banner on opening day, “People’s Justice” (2002). Featuring cartoon-like depictions of activists depicted as dogs, pigs, skeletons and rats struggling under the Suharto regime and foreign intelligence services including the Australian ASIO, MI5, the CIA, and Mossad, the work aims to create a solidarity between all oppressed people. However, among the hundreds of figures is a distinct characterization of an orthodox Jew, with sidelocks, fangs and a hat emblazoned with the Nazi SS emblem. In the London Review of Books, Israeli architect Eyal Weizman points out that “for many artist-activists in Indonesia… the brutality exercised by authoritarian governments at home is bound up with their enablers abroad.” This distance makes it easier for these shadowy international oppressors “to grow crude and monstrous in the imagination.” To some level this explains the unawareness of the severity of the inclusion of the work, though it does not excuse the antisemitism nor the display in Germany. Weizman elaborates:

Hannah Arendt and Aimé Césaire used the metaphor of the boomerang to explain the relationship between antisemitism and colonialism. European fascism, Nazi totalitarianism and the Holocaust were, as they saw it, the homecoming of the racism and violence that European empires had unleashed across the colonial frontier. The boomerang that hit Documenta had another, secondary trajectory, however: having travelled across continents and generations, European antisemitism had returned home in the altered guise of an anti-colonial work of art. And it landed bang in the middle of Friedrichsplatz, which has its own antisemitic history to deal with.

Unlike Lebel’s work, which remains in Berlin, “People’s Justice” was first covered and then removed. Ruangrupa immediately issued an apology. Following the Documenta board’s recommendation to “enter a process of consultation with scholars from the fields of contemporary antisemitism,” ruagrunpa issued a response to “the international press and public to support us in our refusal of censorship.” Here, they highlight the ways in which “Palestinian, pro-Palestinian, Black, and Muslim artists have been targeted and discriminated against by the media, the politicians, and already exposed to censorship by the institution in consequence.” The Documenta board canceled what was to be an open forum to address the initial allegations of antisemitism. According to ruangrupa, what was actually at issue was “that the perspective of the Global South is to be treated as ‘equal.’ Diversity is perceived as a threat to German discursive hegemony.”

Expanding past a top-down structure of a sole curator or even a panel, ruangrupa’s use of rhizomatic curating investigates local versus global. In comparison, Tony Cokes’s non-figurative work requires a close reading of its audience and pushes nuance. By sampling and remixing many sources, there is an author but not always a clear voice, rather it is a multitude.

At their core, biennales are deeply nationalistic. Having evolved from the great exhibitions, world fairs, and salons of the nineteenth century, they are irrevocably intertwined with colonialism, imperialism, and nationalistic soft power. As biennales today strive towards decoloniality, including more women and indigenous artists as well as artists working outside of the “west,” can they continue on this curatorial path without addressing the root of their founding? This founding encompasses a management style, a mode of curation that involves a sole individual directing the program with individual artists standing in for country. The potentiality of what ruangrupa brought was to push beyond a white cube model, one that promotes largely blue chip artists, to bring in the collective. Controversy aside, ruangrupa’s curatorial strategy brought a necessary friction and in some instances unrecognizability of what is expected of a contemporary art exhibition to a cultural landscape that claims for decolonialism yet often presents artwork in reproduced models.