CONTESTED LANDSCAPES

JAMEY STILLINGS TURNS THE AWFUL BEAUTY OF GLOBAL EXTRACTION INTO ART

by Andrew Pasquier

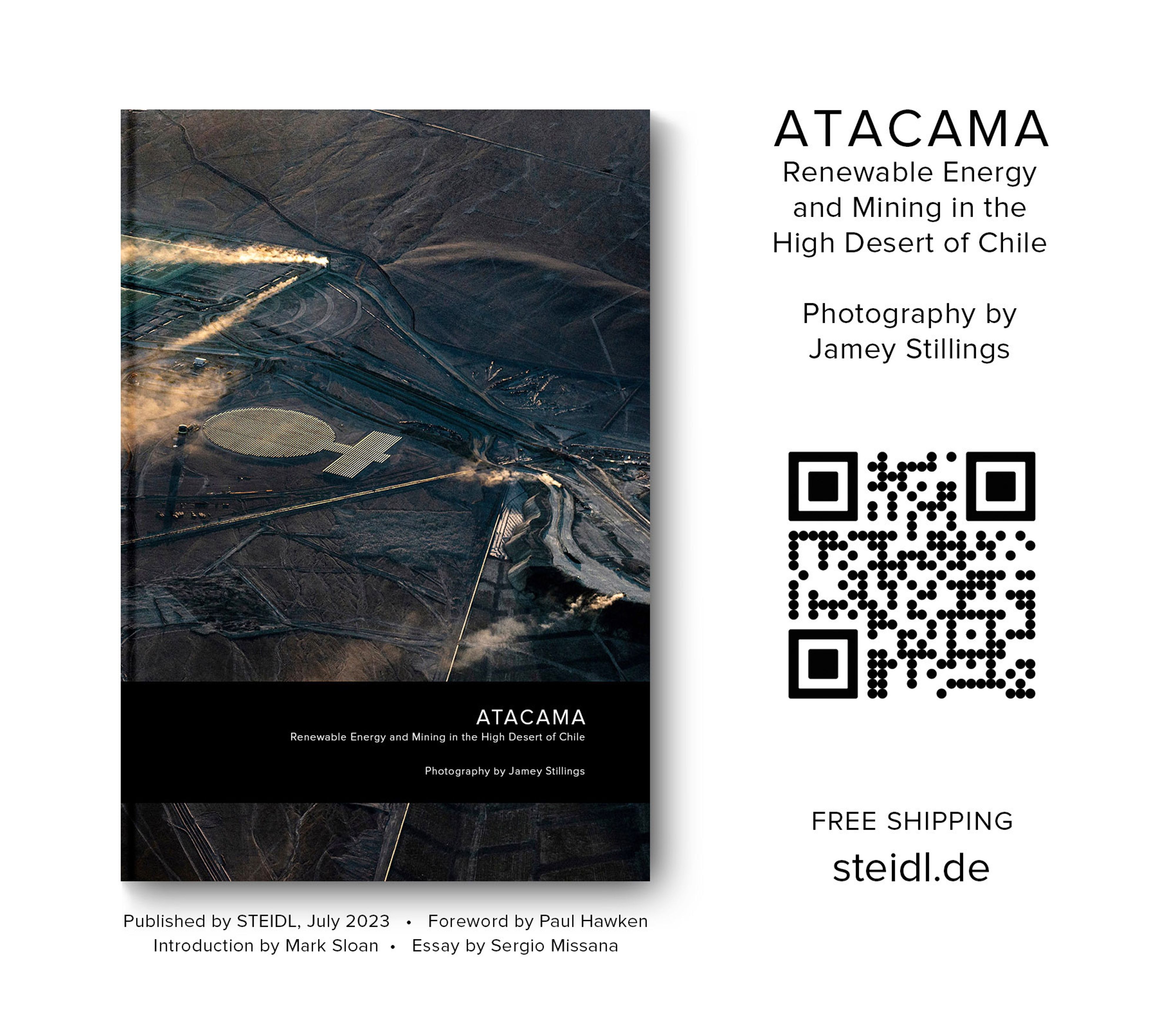

The 97-megawatt Parque Solar Carrera Pinto (foreground) and 141-megawatt Parque Solar Fotovoltaico Luz de Norte supply power to Chilean population centers via the Sistema Eléctrico Nacional (SEN). Parque Solar Carrera Pinto (foreground) and Parque Solar Fotovoltaico Luz de Notre (background), northeast of Copiapó, Chile, 2017. Photography © Jamey Stillings.

Can you see yourself in a lithium mine? Look at your iPhone, your car, your nation’s industrial policy. The rare mineral is a hot commodity thanks to urban emissions targets. To ditch fossil fuels in our cars, we buy more lithium-ion batteries. Which also require cobalt, manganese, and other minerals.

What is less known or appealing to consumer eyes are their sources. Somewhere out there, land is being exploited for our green-energy dreams. People too. Lithium mines in Tibet kill fish and contaminate drinking water. Congolese laborers extract cobalt in life-threatening conditions. The “green gold rush” runs red with blood so Tesla owners can feel righteous driving their new toys off the lot. If alienation from the industrial processes that make modern life possible helped get us into this climate mess, seeing yourself in an open-put mine could be a first step towards honesty.

A good place to start is the Atacama Desert in Chile. The Mars-like expanse is the driest place on earth. It is also home to a quarter of the world’s cooper and lithium production, with Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina’s combined lithium reserves representing over half of estimated global resources. Except for 69 harrowing days in 2010 when 33 trapped miners became a worldwide media sensation, few dedicate much attention to mining operations in Chile. Jamey Stillings, a 68-year-old documentary photographer, is an unlikely obsessive. An environmentalist and expert in aerial photography, he whizzes over contested landscapes — solar fields, mines, dams — capturing the violent symbiosis of man and nature in crisp, uncanny shots.

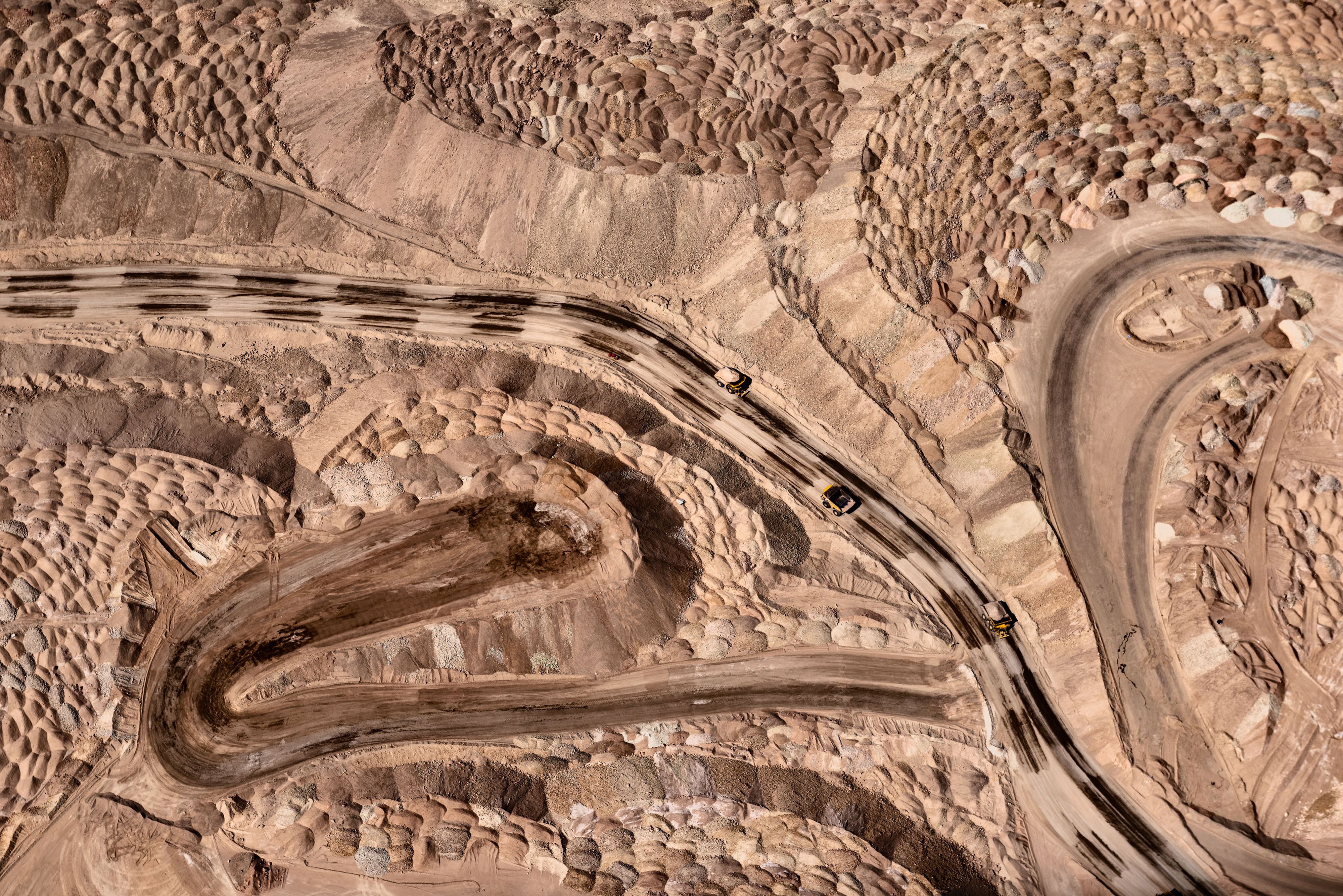

“Some people will go ‘Ew, mining, ugly,’” laments Stillings. Yet his immaculate new photography book ATACAMA (Steidl, 2023) looks at extraction, ties it to renewable energy, and makes it art. In his pictures, sci-fi solar arrays mark geometric patterns across the arid land, and sinuous haul roads and toxic pools evidence our undying thirst for ore. Even in the most desolate images, you can make out traces of human intervention: tyre tracks, a survey mark. “I’m way more interested in the intersection of humanity and nature than in photographing either one by itself,” he comments. “The notion of the human-made geometric against the natural — it’s beautiful.”

Stillings is drawn to places like the Zaldivar copper mines in Chile because of their paradoxes. Finite deposits, buried for millions of years, feed unsustainable contemporary habits. Yet Zaldivar is Chile’s first mine to operate on 100-percent renewable energy. Vast fields of heliostats and wind farms surround the carved-up earth, supplying low-carbon energy to a “dirty” operation, a monumental installation that squares neither with popular notions of environmental stewardship nor consumer-oriented eco-narratives.

Mining is hardly sexy in late capitalism, but the products it enables are — and therein lies the problem. Tesla’s main historical impact is not that it sells electric cars — others came before and after — but that it made driving them attractive to the elites. Sleek design and clever marketing ushered in a new era where appearing to do the right thing became cool, not geeky. The aesthetics of renewable-energy production inform its commercial and political uptake. Personal investments — like putting solar panels on your roof or driving an EV — can earn you social credit in the marketplace of political virtue signaling. As designed objects, these technologies are easy to grasp and sell.

This 27.5-megawatt solar thermal array Pampa Elvira Solar, 75 miles southwest of Calama, Chile, supplies the majority of the thermal energy needed for a metal-extraction process called electrowinning at Minera Gaby. Pama Elvira Solar, Minera Gaby, 120 km southwest of Calama, Chile, 2017. Photography @ Jamey Stillings.

But what about large-scale energy projects? While there is something cinematic about the silhouette of wind turbines or cooling towers dotting the horizon, by and large, modern culture insulates us from the sites and means of energy production. When these infrastructures do come closer into view, people freak. Donald Trump famously claimed wind turbines cause cancer. While few concur, many educated and “progressive” people in the U.S. concoct all sorts of reasons to oppose wind farms. Take the decade-long fight to place 130 turbines in the shallow waters of the Nantucket Sound, obstructing the summer-home views of billionaires of both sides of the political spectrum. The project is now dead. New York’s first offshore wind farm is currently dividing the Hamptons. “One guy I play tennis with wants to stop the project,” a retired lawyer mused to The Guardian. “We try not to talk about it at all.” Unsurprisingly, studies find that wealthy white communities are the most likely to oppose wind-energy farms.

Stillings describes his practice as bait and switch: lure people in with stunning images, then educate. “In my photography, I try to flow between the informational — ‘What does this mine look like? What does it do?’ — and the visual — ‘What will cause the viewer to pause, and in pausing, perhaps absorb more information?’” The way Stillings straddles aesthetic and analytical modes renders his photography prescriptive, with the bluntness of photojournalism. Yet, critically, the self-described environmental activist remains optimistic, committed to spreading can-do narratives. “Over 90 percent of the imagery about climate change and pollution focuses on the symptoms — I have a ton of colleagues and close friends who have photographed the melting glaciers or huge dumps of plastic.” Instead, his work incites awe towards the technological infrastructure of renewables, a transformation that is not only possible but in motion.

There’s a solarpunk dimension to Stillings’ vision. His work is neither utopian nor nihilistic. Moving beyond the alienation of movements like cyberpunk or the retro-obsessiveness of steampunk, Stillings makes art that celebrates technology’s capacity to enable humanity to better co-exist with the environment in the future.

Yet, the seriousness and vastness of his aerial shots belie the “punk” spirit. There are no stained-glass solar panels, no pretty flowers, no DIY ethos that recall solarpunk’s uplifting message that individuals play a role in solving planetary problems. Instead, the dark and sleek symmetry of mining and energy operations in the Atacama Desert recalls the techno-power of international corporations and the state. Looking down at the “wasteland” of the Atacama is humbling. Yet Stillings asks audiences to wrestle against the slide towards deindividuation and instead see their tiny mark, an invisible Waldo, on the landscape. “You are using Chilean copper every day of your life; you are using Chilean lithium every day of your life. Let’s get real: we are those mines.”

Stillings frequently circles back to ask himself a nagging question, one that applies to all art-as-activism: “Has my work moved the needle?” Stalling climate action provides a bleak answer. But for the collective needle to move, people need first to recognize themselves in it to care. Stillings trains our eyes on the awful beauty of the energy transition, capturing the Atacama with haunting precision.

A small section of the Chuquicamata mine in Chile reveals the vast quantity of waste rock produced during open-pit copper mining. Mina Chuquicamata, north of Calama, Chile, 2017. Photography @ Jamey Stillings.