How has your relationship to creating contexts for viewing art changed over the years?

KH: Art spaces are really tough. Though collections have become increasingly global, which is good, I don’t see it reflected in the architecture of any building. I wish things could evolve more.

CB: I think in general, at least in the West, we’re heading toward more reuse. Why build a new space if there are so many post-industrial buildings around?

KH: But that’s Tate Modern — you guys already did that 25 years ago. Richard and I used to talk about this: why have so many of our brilliant architect friends failed at building a good museum? To this day, there are still more bad museums than good ones. We concluded that it must be the archetype of the museum. We wanted a new architectural narrative. I think we succeeded as much as we could with the Walker. The multidisciplinary nature of the Walker was a beacon. But I often wonder: if we weren’t all white people of European extraction, would we have a different image in our heads of what a museum should be like and function? I think we might. I think about this a lot, because it seems to me museums should be the apex of diversity. A few years ago, I was on the jury for the M+ competition in Hong Kong. Every great architect I admire presented. I dimly remember there were attempts to make things that were culturally specific — one architect even made a roof shaped like a coolie hat, which made me shudder. The cultural references are usually very mundane because we really don’t have a language for this yet. Herzog & de Meuron made the most of the site, and they rightfully won the competition. I’m curious, Christine: what did the team come back and say about these things? Were there conversations? Did the building’s location in Hong Kong have any influence on the museum’s formal or conceptual attributes?

CB: Well, formally speaking, the cladding is dark-green ceramic, which is a local reference to the architecture of the place. But it was much more about what we found on the site, which was a landfill. All we had was an existing underground tunnel, a physical piece of infrastructure, to work around. At first we thought it was a problem, because it cut through the site diagonally, but we decided to use it as something to react to, to use its force. Of course we try to identify and react to local specificities, both physical and mental. When you build a museum in a city where there is no comparable cultural space, you have to expect huge visitor numbers and design for that. This thinking informs the bolder gestures of M+ — the large lobbies, but also the giant screen that faces the harbor.

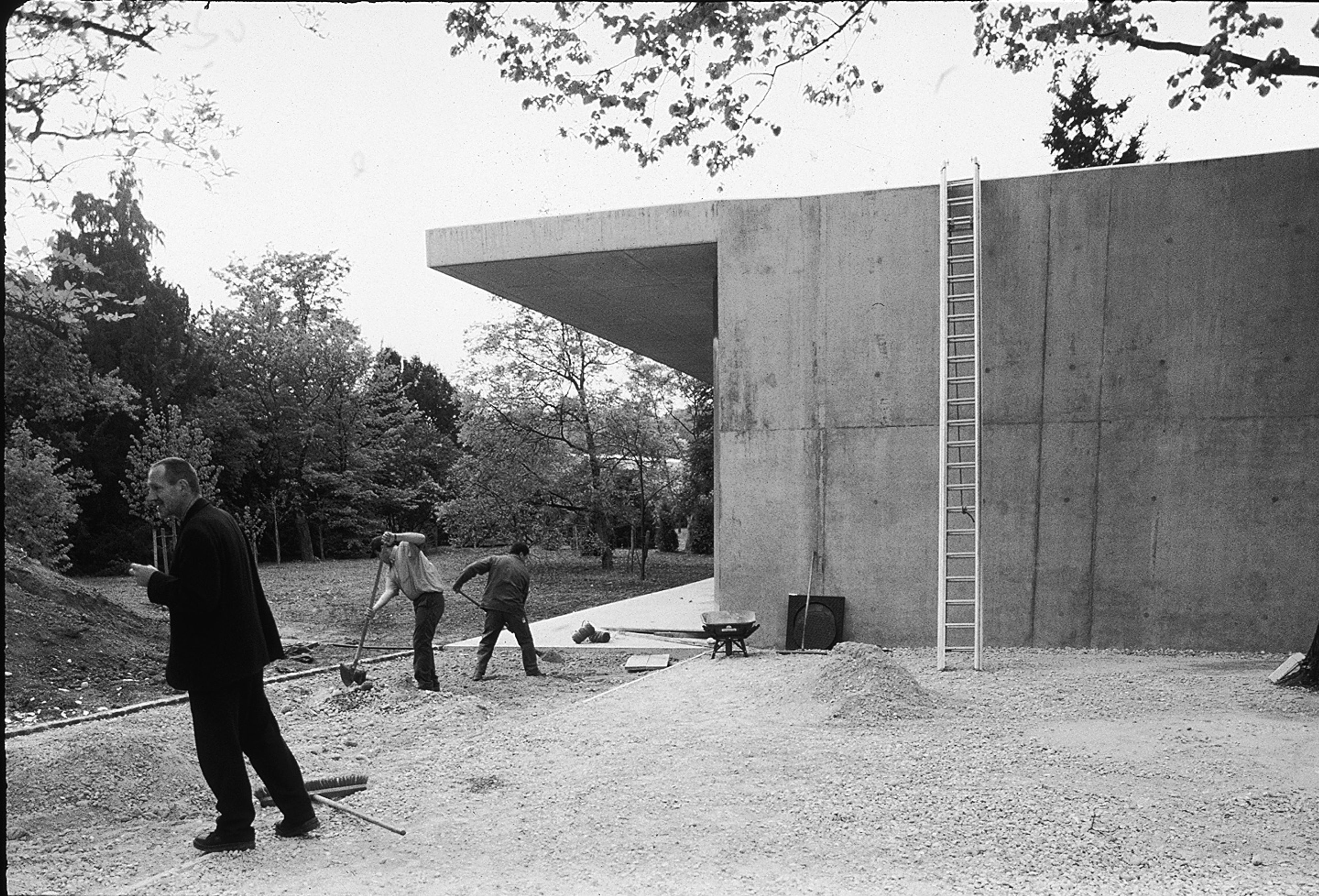

KH: I think what Christine just said is really important. We talk about the museum, but actually it’s always a museum. Scale, context, and collection make every single project unique. At M+ or MoMA, for example, you have to design an abundance of unprogrammed space, which often has a corporate feel, because people have to figure out immediately how to circulate. So there are restraints put on you. And I think Herzog & de Meuron understands restraint. At one point, we ran into a terrible financial situation at the Walker, and we didn’t know if the building would be completed. Remember that, Christine? We ended up value-engineering out a huge slice of space, and it was a painful process. But Herzog & de Meuron were brilliant and knew how to make use of the restraints, so the building got better because of the so-called compromises.