Minoru Yamasaki and assistant with Model of World Trade Center, c 1969. Photo by Balthazar Korab (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Demolition of Pruitt-Igoe Apartments, April 22, 1972. US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

A 1978 postcard sent by my dad to my aunt sits on my desk. It shows the Statue of Liberty toppled into the harbor, as if drowning. Her crown and half her torso are submerged, but the torch-bearing arm remains above the water. The downtown Manhattan skyline—most prominently architect Minoru Yamasaki’s World Trade Center Twin Towers (1964–73) — stands behind the sinking statue. Looking at this image now, it presents an alternate history, the death of one monument in place of another, drowned in the river instead of engulfed in flames, obvious though apt in its metaphor: the promise of America’s ideological purity toppled, while the landscape of its capitalism remains triumphant.

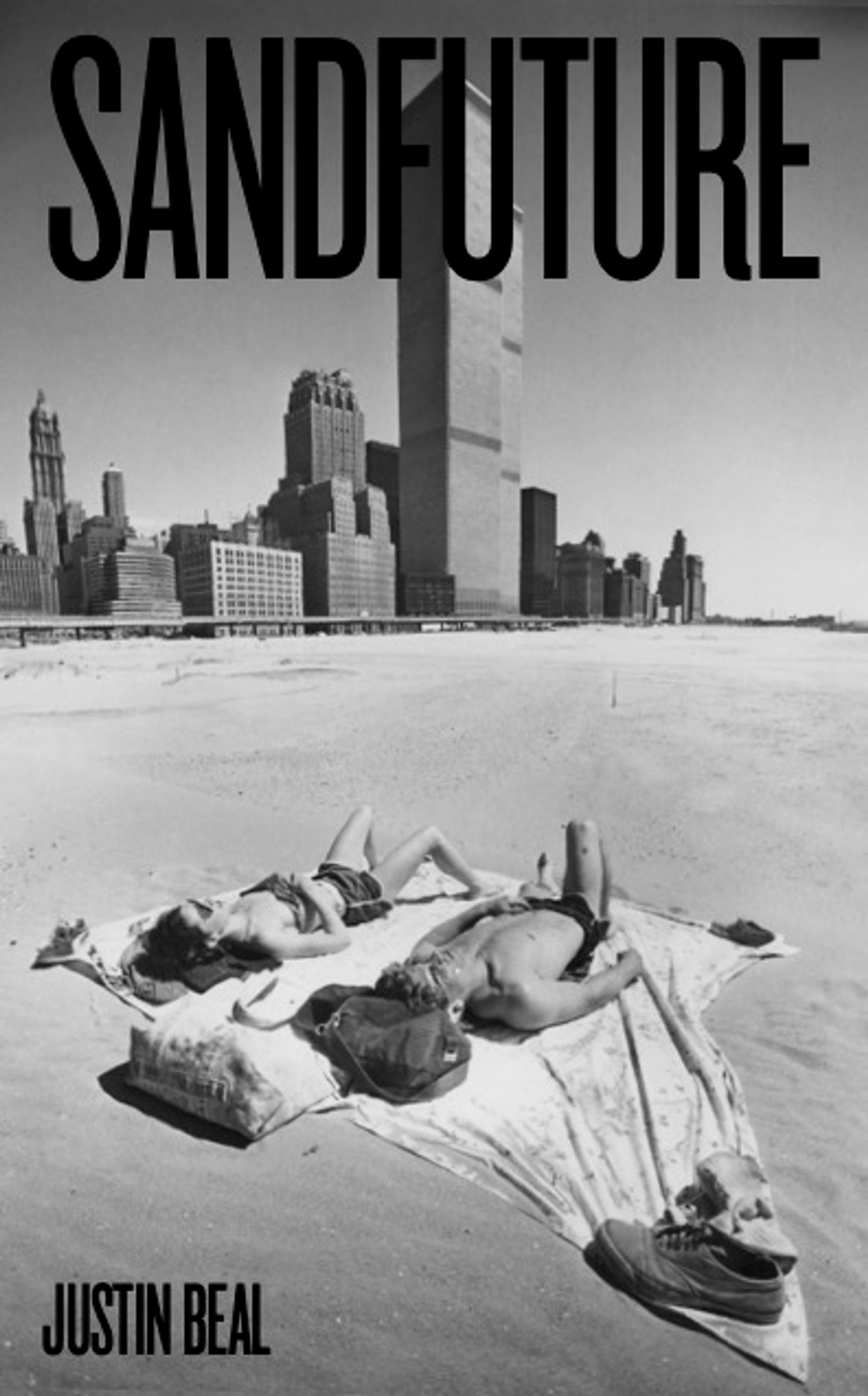

I thought of this image often as I read Sandfuture, Justin Beal’s elegiac and genre-defiant book, part biography of Yamasaki, part personal memoir of navigating a New York City deluged with floodwaters, supertall luxury towers, extreme inequality, and migraine triggers. The cover photograph — two sunbathers beneath the Twin Towers on an ersatz beach made from all the dirt and rubble excavated from the World Trade Center site (today Battery Park City) — is its own sort of alternate history, taken in 1977, shortly after the city’s 1975 bankruptcy crisis, when the towers seemed extravagant and superfluous.“ This couple could be the last two humans on Earth,” Beal writes, “ecstatic and oblivious, deserted on a beach that seems to stretch to the distant stanchions of the Verrazano Bridge on the horizon” — a vision of the quiet, stolen future of a city frozen in a state of arrested development.

Minoru Yamasaki and assistant with Model of World Trade Center, c 1969. Photo by Balthazar Korab (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

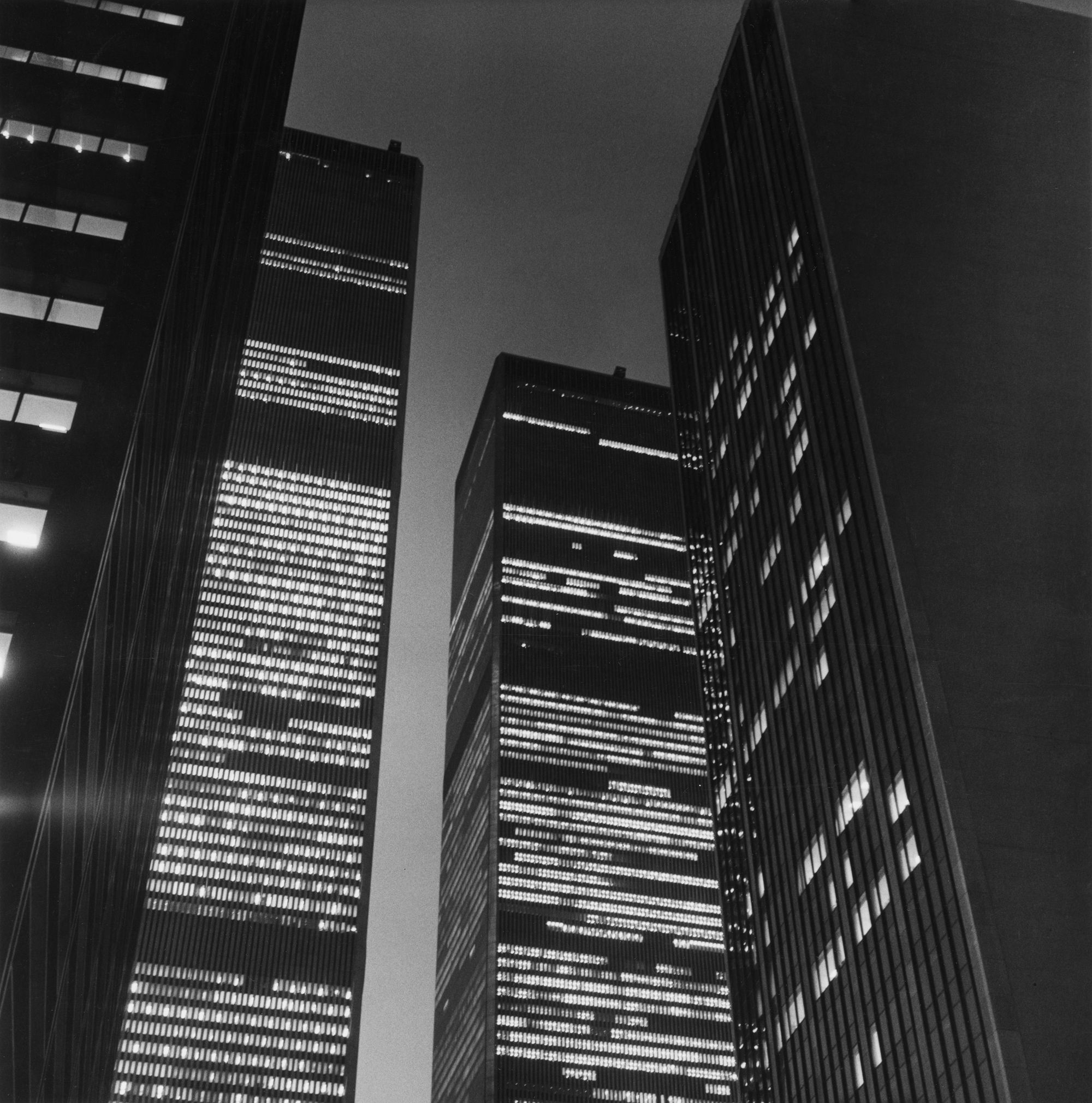

World Trade Center at Night, 1976, vintage gelatin silver print, 20x 16 inches © 1987. Photo by Peter Hujar (courtesy The Peter Hujar Arch, Pace Gallery, New York and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco).

As biography, Sandfuture recounts Yamasaki’s corporate, educational, and international commissions, focusing on the mounting critical consensus around his work (mostly unfavorable: too decorative for the Modernists), and addresses the racism he faced as a Japanese American after World War II, his multiple marriages, and his health problems. Beal seeks to understand Yamasaki both as an architect and a person: we learn of his deep commitment to a humanist philosophy and his belief that architecture is “the effort of mankind to instill into his constructed environment the quality of aspiration toward nobility which will inspire in him the pursuit of happiness.” But Sandfuture also reads like autofiction, meandering into Beal’s personal life, his thoughts on the global art market, encounters with the pharmaceutical industry, personal recollections of 9/11, and Hurricane Sandy. One of Beal’s most fascinating digressions is on the persistent architectural metaphor of buildings as bodies, beginning with Vitruvius. “Any house is a far-too-complicated, clumsy, fussy, mechanical counterfeit of the human body,” he quotes from Frank Lloyd Wright, and later muses on the sick-building syndrome (toxicity-laden architecture that harms its inhabitants—note that that the building itself, and not those inside it, is deemed ill). After Hurricane Sandy, he writes that the Chelsea building which housed his partner’s gallery, rigged with pumps, vacuums, and generators, “looked like a body on life-support.”

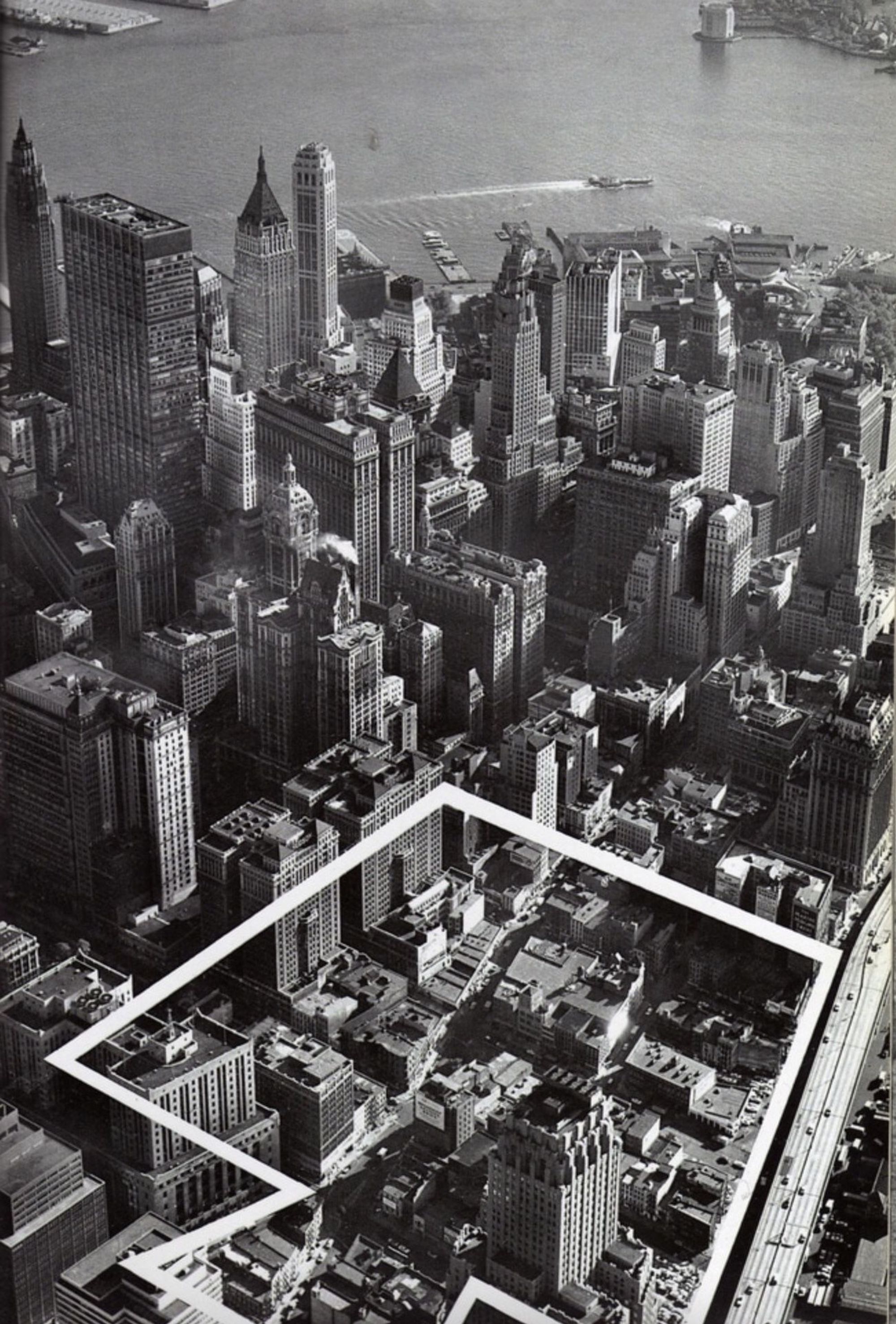

Aerial photograph of the future site of the World Trade Center. Found in 1963/64 Special Issue of “Via Port of New York”.

Battery Park Beach, May 15, 1977, Photo by Fred R Conrad (courtesy ofThe New York Times/Redux).

Extending these anthropomorphic metaphors, one is tempted to talk of the life and death of buildings. This is fitting for Sandfuture, for perhaps no architect is more associated with architectural death than Yamasaki. It is impossible to consider his practice without contemplating the spectacular demise of his two biggest commissions: the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Complex in St. Louis (1951–55, demolished 1972–76) and the World Trade Center. The destruction of both was broadcastlive on TV some 30 years apart, and Beal manages to narrate the death throes of these buildings with a care and sensitivity that architectural historians (such as Charles Jencks, who claimed that the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe was the “death of modern architecture”) have often elided. In his proximity to the towers on 9/11, Beal puts words to something that I, also just a few blocks from the towers that day as a child, have struggled to articulate over the last 20 years, namely his hesitancy to discuss what happened as he grapples with “the absurdity of laying claim to the single most significant global event of the new century as something that also felt so intimate and so intensely my own.” For the reality is that buildings are not lives but are lived in, a distinction Beal is keenly aware of in his narrative, Rafael Viñoly’s supertall 432 Park stands as the perfect villain precisely because it is not lived in, but passed through, a largely uninhabited vehicle for wealth and financial speculation.

Yamasaki & Associates, Century Plaza Towers and Century City Hotel (Century City Los Angeles, California 1961-1966 and 1968-1975). Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Sandfuture leaves many of its multiple threads dangling, unfinished. Despite this irresolution, the book is a laudable attempt to forge a new breed of hybrid architectural history that remains embodied throughout. It is a particularly fitting project to attempt with Yamasaki, an architect committed, however naively, to the promise of humanism.