Beatrice Bonino, Senza tittolo, 2023, ceramic. Photo by William Jess Laird courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

If I did, I did, I die, Beatrice Bonino, Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery. Photo by Diego Villareal courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

“Do you all like Home Depot?” Paris-based artist Beatrice Bonino posed the question this past December at an old school-style salon organized by gallerist Jacqueline Sullivan and curator Vere van Gool. The question wasn’t totally out of bounds — the conversation had turned to the aesthetics of the mundane — but its pointed interest in the mecca of everyday building materials hinted at what Bonino had in store for her American solo debut at this same gallery, If I did, I did, I die, which opened at the end of February — the first show in Sullivan’s space dedicated to a singular artist’s body of work.

Those who have been to Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery for the salon or its previous show, Substance in a Cushion, will walk into quite a different space for Bonnino’s solo exhibition: as an artist and sculptor who often works as a set designer, the layout of her new works is taken into great consideration. A slightly-translucent sheet of latex curtain hangs down, bisecting the room. As Sullivan describes, there is an intimacy to Bonnino’s work that demands to be viewed up close and personal.

Beatrice Bonino, Senza tittolo, 2023, ceramic. Photo by William Jess Laird courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

Beatrice Bonino, Senza titolo, 2023. Ceramic, cellophane, lead,rubber, pins. Photo by Diego Villareal courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

This curtain might be someone’s first hint as they walk into the space that the materials used here are more pedestrian — possible to have found at Home Depot, is what I mean — than their delicate shapes might typically indicate. Bonino made all the works in the show during her time visiting New York in the three months leading up to its opening, and she made most of them in Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery itself. Knowing this, the space of the exhibition takes on the feeling of a magpie’s nest: many of the materials are found objects or textiles from the neighborhood, brought back to make something beautiful within the walls of the gallery.

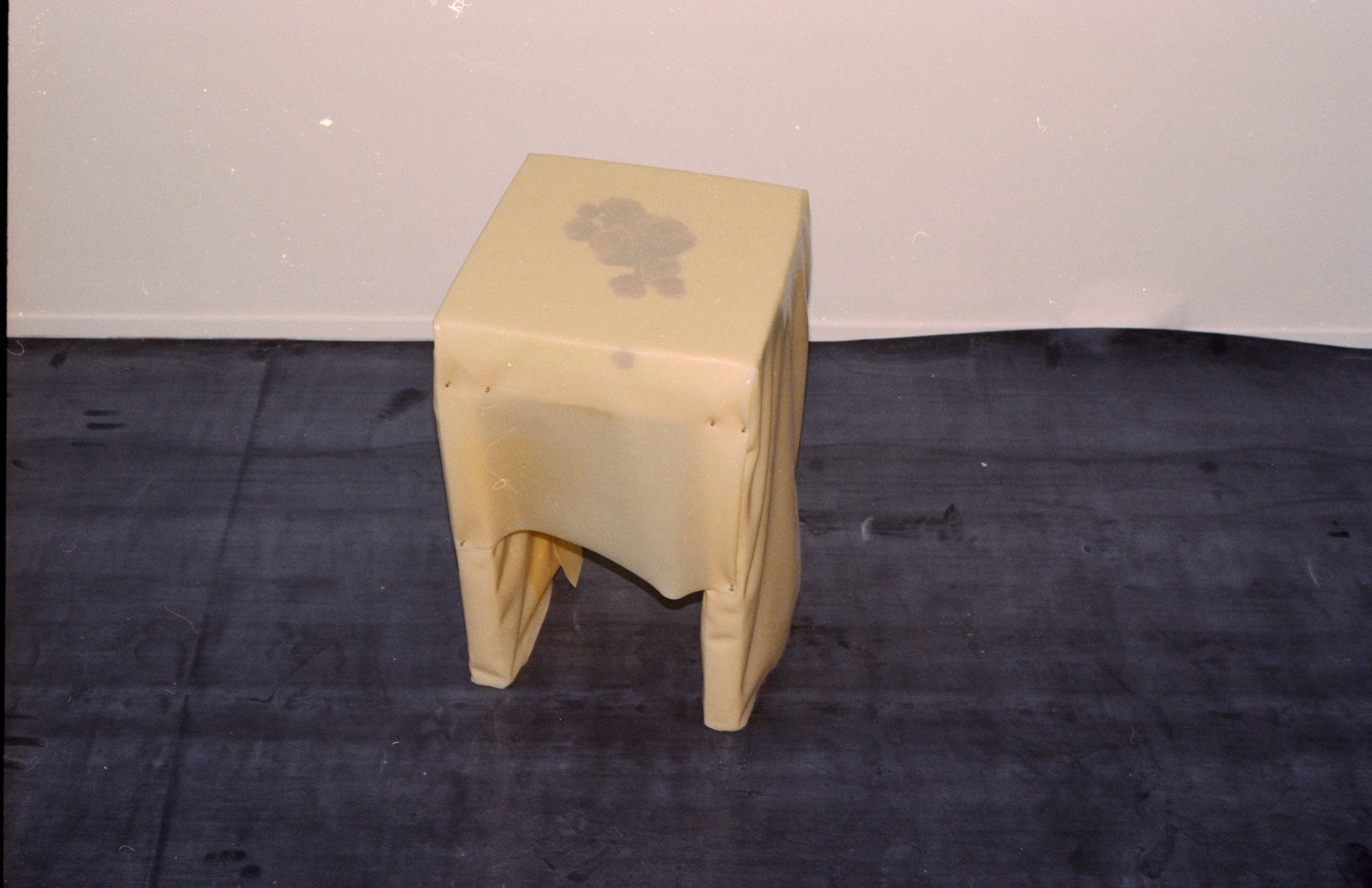

One of the best examples of this is one of the four stools shown in the space, covered in what appears to be a new textile created by Bonino; in fact, it’s a rose-printed bodega bag covered tightly in clear plastic. In true magpie form, Bonino asked a woman on the street for the bag, not yet knowing that this particular print can be found at any corner deli, betraying a curiosity that comes with being in a new place. The freshness of her approach comes through in subtle details, and allowed me to look at subway grates and bodega bags with new eyes when I left the show for the streets of Tribeca. Her references to traditional domestic spaces kept me thinking about them long after I left the space.

Exhibition view of If I did, I did, I die by Beatrice Bonino at Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery. Photo by Diego Villareal courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

Walking through the gallery, a visitor is greeted by clay pots dressed in vinyl and silk, affixed in place laboriously and against the material’s wishes; they look a bit like bellies being dressed in skirts that don’t quite want to stay closed. It’s what I might imagine artist and Puppets and Puppets designer Carly Mark might do if she turned from clothing to visual art rather than the other way around. After I left the show, these pieces with their visible, slightly strained bindings made me think of the classic material question attributed to architect Louis Khan: “What do you want, brick?” In his case, he was posing this question to gain inspiration from the natural tendencies — and maybe desires — of the materials he was using, but in Bonino’s case, she is finding inspiration from exactly the opposite. She describes one of the themes of this show by illustrating her interest in the way certain materials resist her work: affixing latex, plastics, and silk with wood and nails; weaving with steel wool, and tying bows with lead; or covering a bench in Calvin Klein deadstock fabric.

This interest in fastening comes across in elements that show off Bonino’s work as a set designer, too. For example, it becomes clear that the plinths displaying her sculptures and their plexiglass cases are meant to be part of each piece — not just while the exhibition is on view — when you see how their vitrines are fastened together with visible adhesive. Her attention to scenography extends to latex covers for the outlets of the space, and to the skirt that covers the bottom of the sink in the restroom.

Exhibition view of If I did, I did, I die by Beatrice Bonino at Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery. Photo by William Jess Laird courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

Bonino’s show also continues the gallery’s young but clear tradition of publications that are explicitly not catalogs, one that I hope will continue to be an integral part of Sullivan’s curation. In this case, the experience of seeing photographer Diego Villareal’s photos of Bonino’s works added a new dimension to the show; his images convey what it’s really like to see these pieces in person. The fact that the artist editions of this publication are bound in latex with rhinestone lettering doesn’t hurt, either.

When I asked about her fondness for bows, Bonino replied, “It’s just another way of fastening something.” And in this case, much of her interest in fastening is in attaching memories to the space — perhaps in part due to having used the gallery space as a studio for months — in part inspired by the mnemonic device detailed in The Art of Memory by historian Frances Yates. In this historical study, Yates walks through the concept of imagining a speech as if it were a physical space —a Roman villa, for example — and picturing oneself walking through it while reciting the words, attaching memories to different columns, plants and other markers in the imagined room in order to bring the text to mind. For Bonino’s If I did, I did, I die, this imbues each piece with the narrative of its own making.

Beatrice Bonino, Senza titolo, 2023. Ceramic, plastic, rhinestones. Photo by William Jess Laird courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

Beatrice Bonino, Senza titolo, 2023. Latex, plastic roses, plastic. Photo by William Jess Laird courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

Beatrice Bonino, Senza titolo, 2023. Wood, foam, latex, plasticroses, nails, rhinestones. Photo by Diego Villareal courtesy of Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery.

For Sullivan, this play between permanence and permeation is one of the aspects that makes the space one to watch, and this show builds off its last. And the same goes for this line between art and design: at the salon I mentioned earlier, one of the points of contention was that art is never finished, whereas it’s clear when a piece of design reaches its ultimate form; it becomes functional when it fills a role. But if artworks can never be complete, where does a gallery show come into play? For Bonino, these objects would be at home in someone else’s, but it’s not the function she’s after. “Works like these exist in my home, but my place is a bit like a museum itself.”

My favorite piece in the show is a black latex-covered stool that is placed within an arts and crafts cabinet from the 1800s, which was included in the inaugural show of the gallery. As Sullivan describes it, “By showcasing contemporary editions alongside important historical pieces, the gallery hopes to stimulate an antiquarian inquisitiveness,” and this instinct brings a delightful new approach to what a design gallery can be.