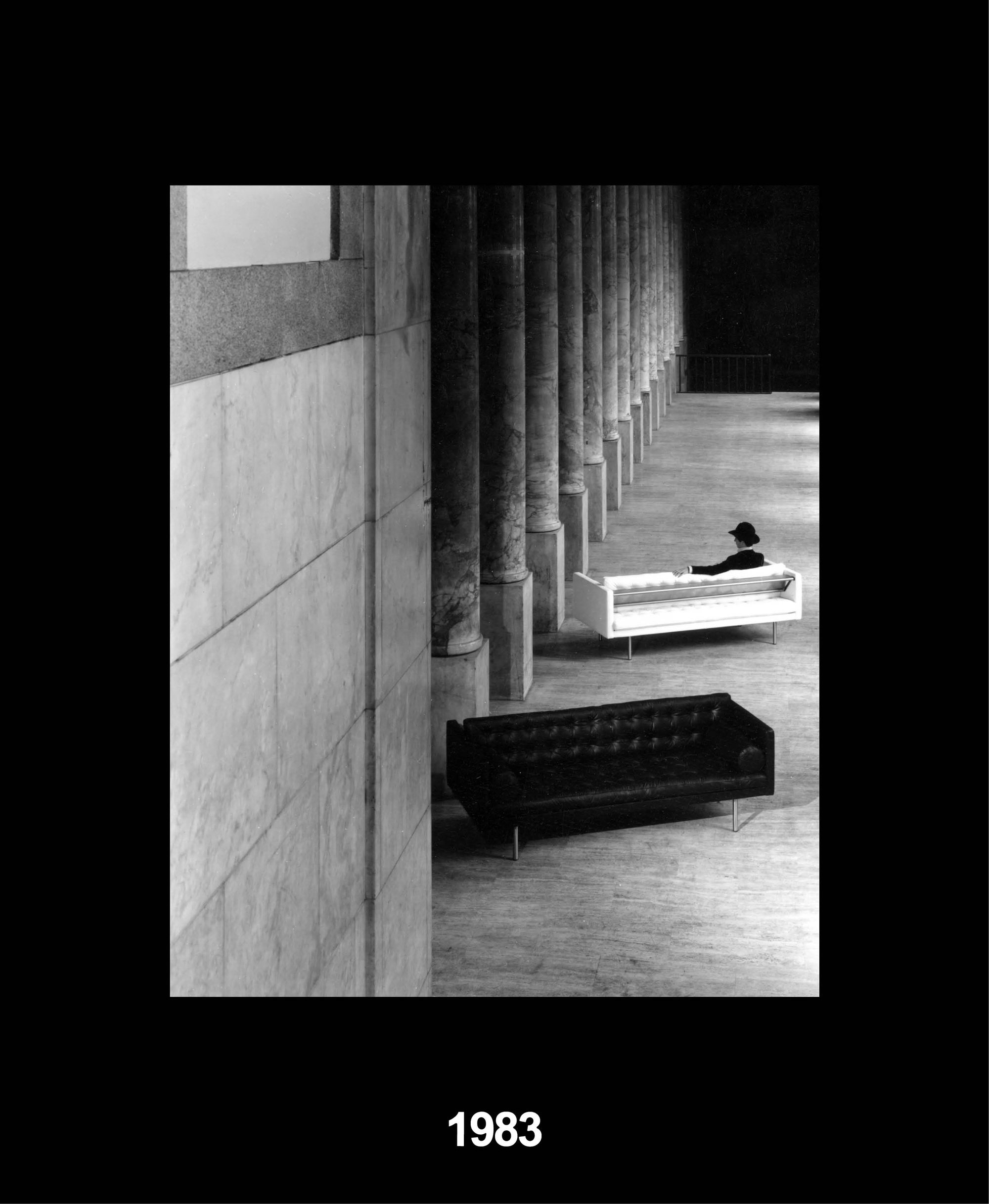

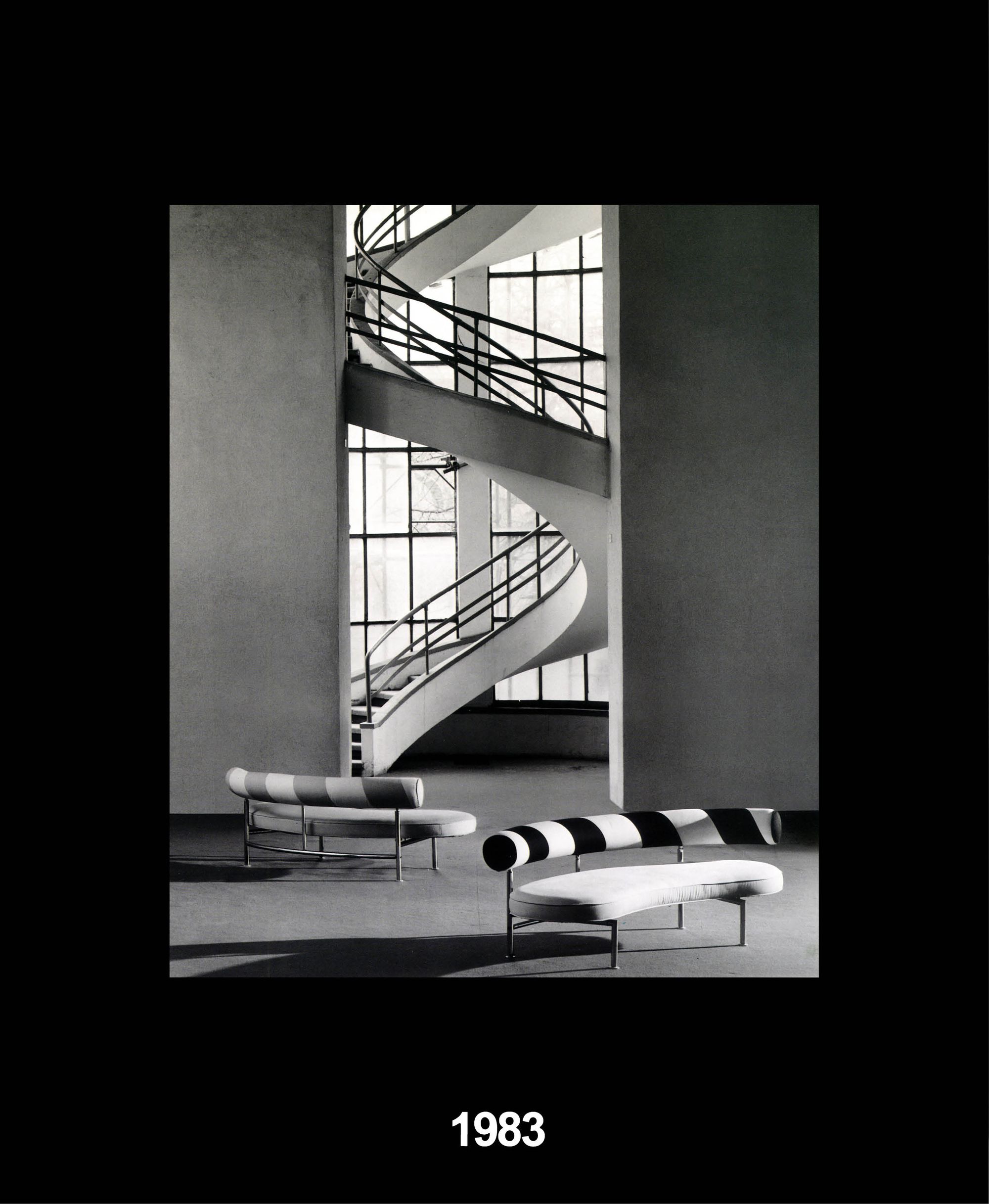

Founded in Meda in 1959, Flexform is one of many groundbreaking postwar family companies in the region just north of Milan, historically known for excellent woodwork and cabinetry. What sets Flexform’s products apart from its competitors is their superior quality and their discrete elegance. “It’s a natural, quotidian attitude,” says Antonio Citterio, the renowned architect and designer who’s worked for Flexform and its owners, the Galimberti family, since the 1970s. One of Citterio’s most famous designs for Flexform, the Max sofa, took on a more flamboyant character than most of its sister sofas. The “banana-shaped” two-seater was released in 1983 and was accompanied by an influential campaign shot by the late architecture photographer Gabriele Basilico. His immortalizations of Max and Citterio’s other designs, like the Magister sofa, set a precedent for Flexform’s creative expression over the following decades. (Graphic designer Natalia Corbetta also played an essential role in setting this high bar). To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Max, Flexform debuted SuperMax, an updated, more generously proportioned version of the iconic piece, which was photographed specially for PIN–UP by Leonardo Scotti. Felix Burrichter met with Citterio to reflect on a vital moment in Milanese design history, when friendships, creative energies, and Flexform’s extraordinary craftsmanship galvanized into an enduring legacy.