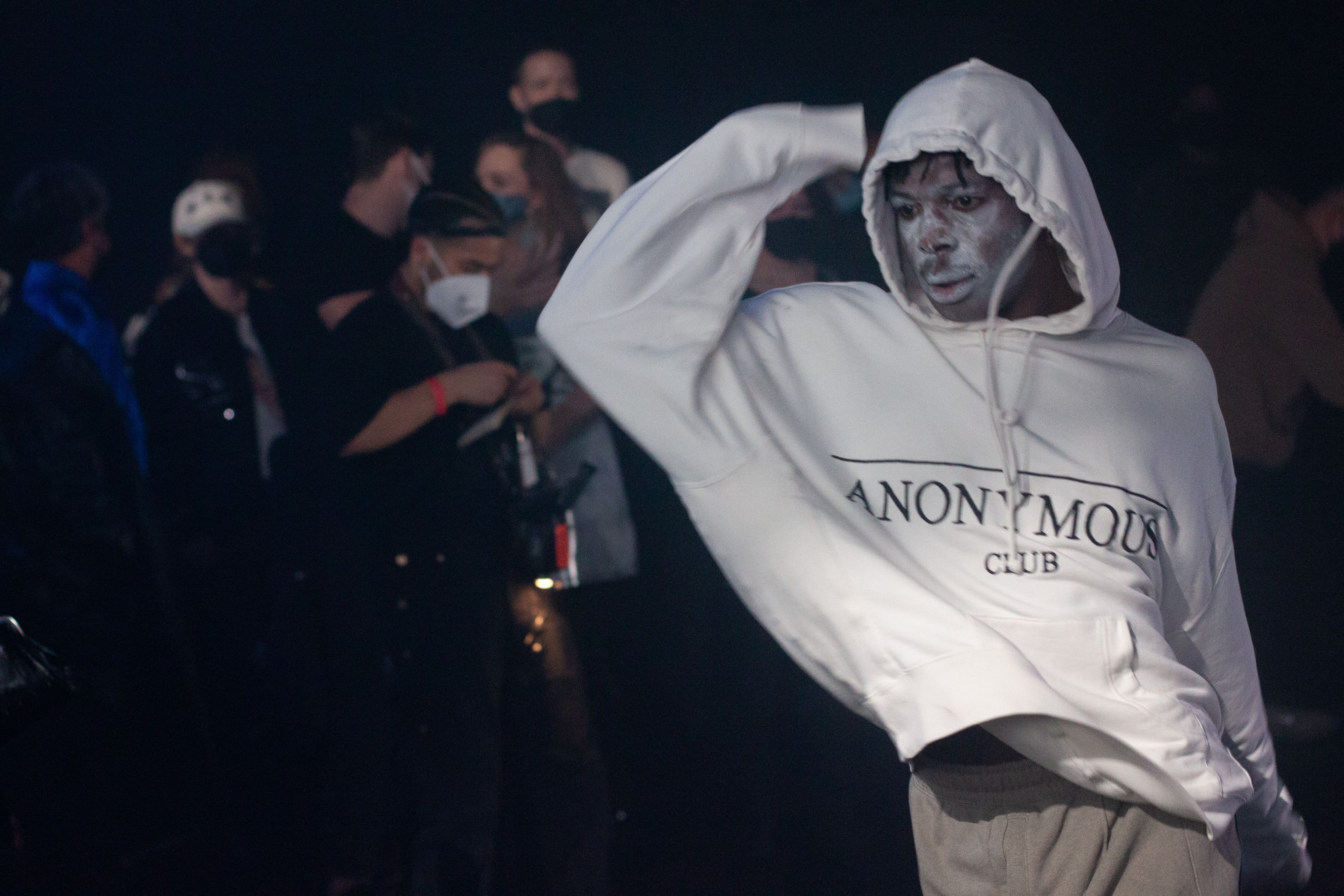

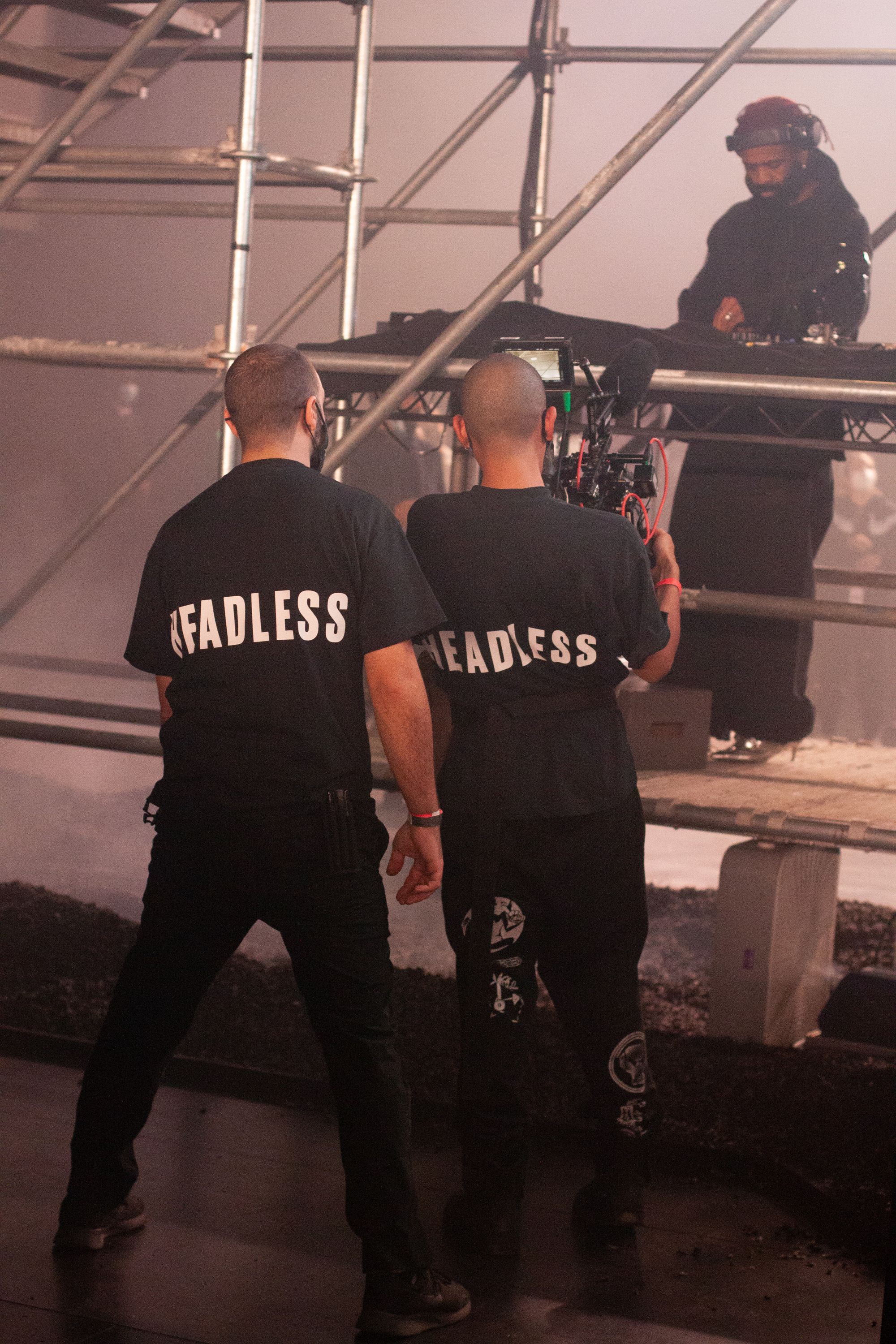

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Anonymous Club’s first project didn’t so much shatter the proverbial glass ceiling as build one on its own terms — in Zürich, Switzerland, in the middle of the pandemic, no less. Shayne Oliver launched the residency project and creative incubation studio with Glass Ceiling, an exhibition and series of events at Luma Westbau that stretched from the fall of 2020 into the spring of the following year. Avatars and digital stand-ins inhabited the slick exhibition design by Niklas Bildstein Zaar and Andrea Faraguna of sub, a literal glass ceiling held up by a grid of white pillars — spectral and sterile all at once, a prophecy of retail’s dystopian future. Seamlessly combining music, architecture, fashion, and performance art, Glass Ceiling was emblematic of Anonymous Club’s broader aims. “It’s not a gallery. It’s not a runway. It’s not a concert,” explains Oliver following HEADLESS: The Demonstration, the collective’s three-night takeover of The Shed during the Fall Winter 2022 New York Fashion Week. “It’s a grouping of all that stuff.”

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

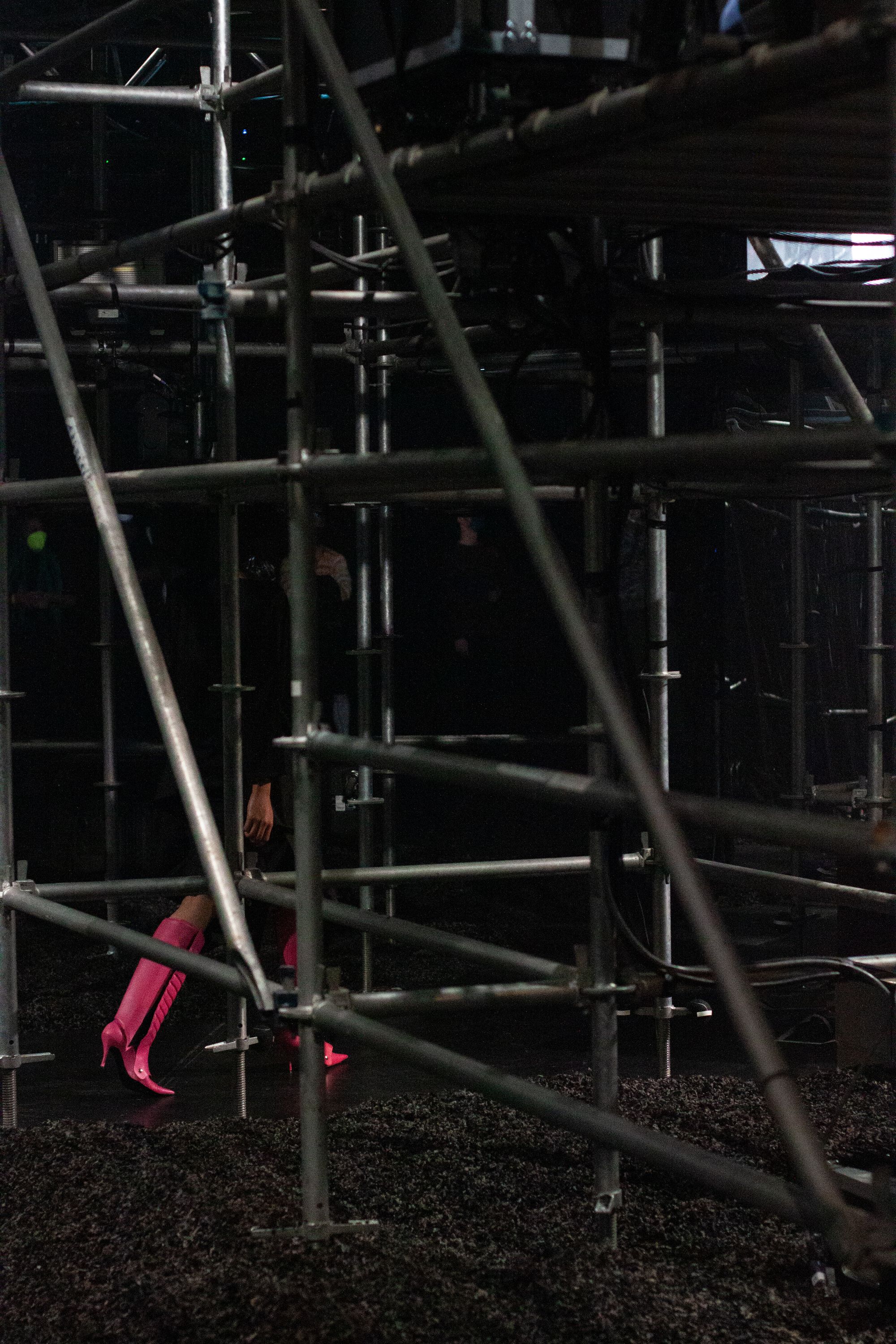

A detail of the “monolith” the main piece of set design at Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

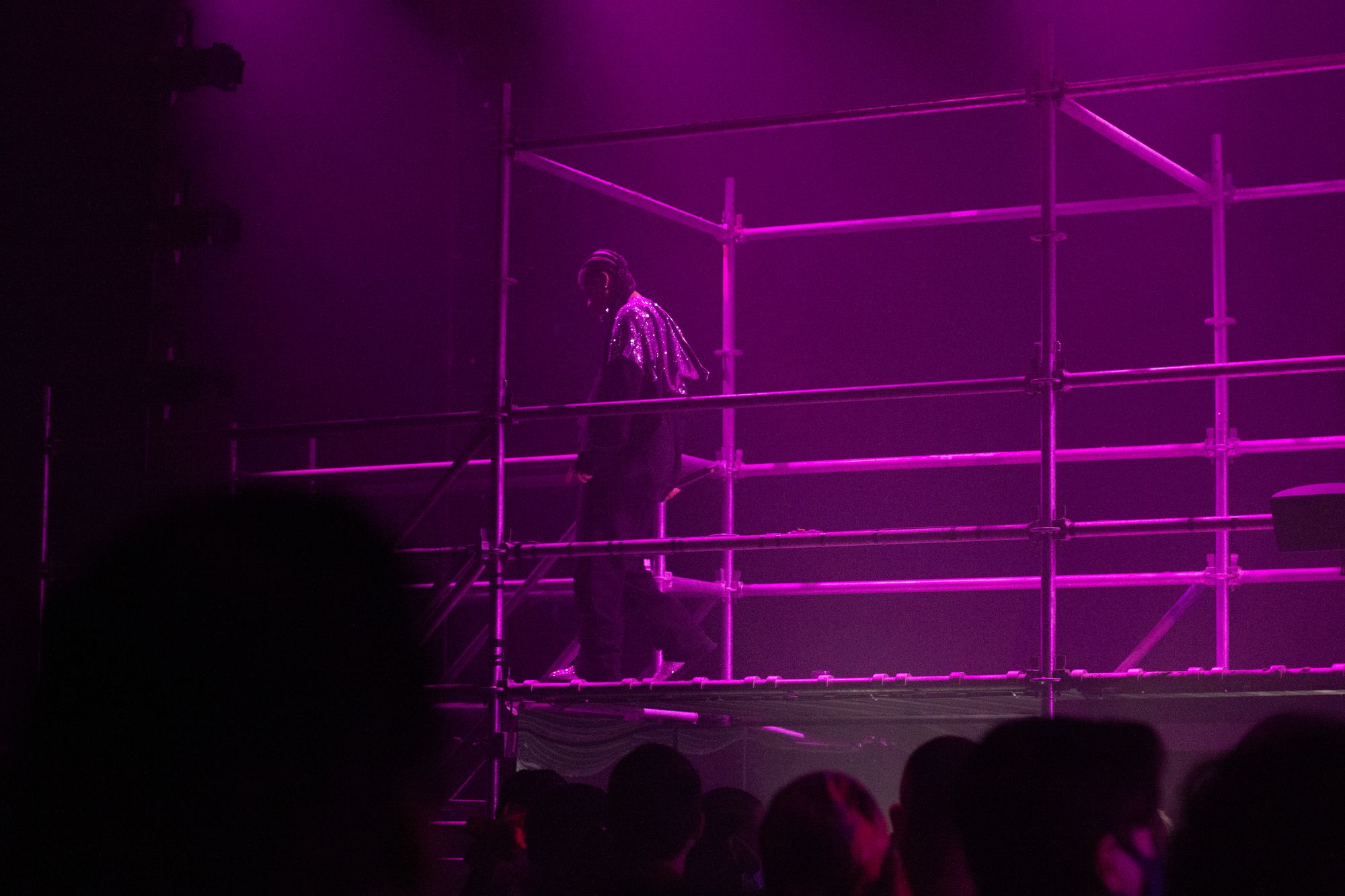

The fashion presentation at Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Oliver first started experimenting with these ideas in 2006 when he founded the provocative fashion label Hood By Air (HBA) with Raul Lopez. Anonymous Club throws even more intention behind the way HBA cross-pollinated scenes, bridging the art world, high fashion, and queer club culture with a certain strain of Black cynicism that Oliver remembers didn’t go down so easily 16 years ago. Some people thought HBA had lucked out, or were condescendingly surprised when they could identify references to, for example, post-capitalist decline. Looking back, Oliver uses the metaphor of a construction site to explain this initial reaction. “Construction is loud and tedious — building a house is gross, rambunctious, and annoying. But I don’t know if people understood that we knew that from the beginning.” HBA’s brand of steely cleverness should have fit right in with European anti-fashion history, but the greater cultural discourse churned out shallow buzzwords — urban streetwear, androgyny, avant-garde — with a lacquer of skepticism that glossed over how serious the ideas were that Oliver and his cohort wrapped up in HBA’s designs.

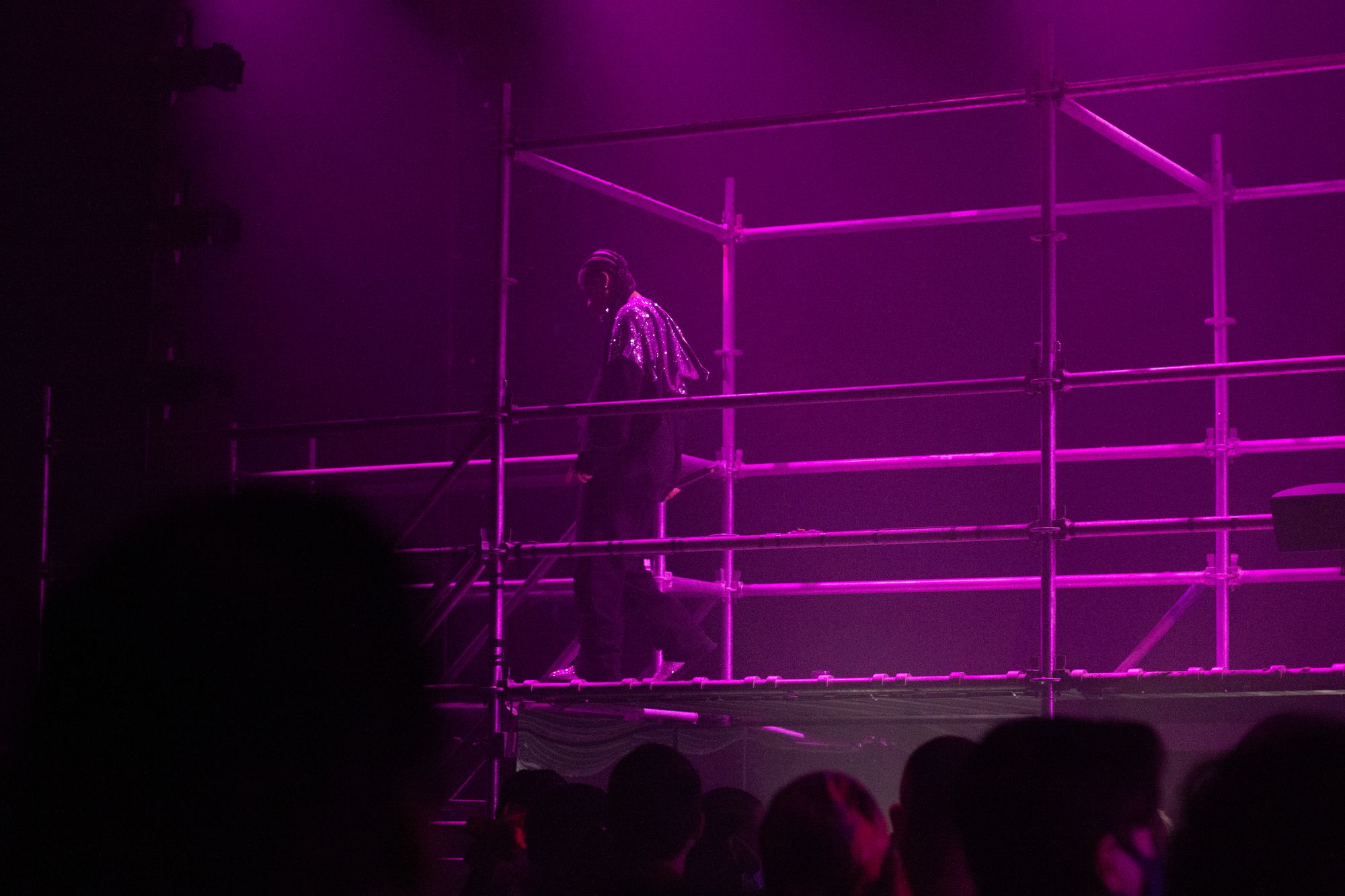

A close-up of the “monolith” at Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

With Anonymous Club, Oliver builds off these small moments in HBA’s history that may have been perceived as “fumbling” — runway shows where the music was too loud or the lights too dim — and creates an environment where this work can live and breathe without being held up to staid expectations. “We want to create a format for a kind of event that is all-encompassing — of sound, of installation — where people understand it’s not a mistake, without playing to the runway-stage rulebook,” he explains.

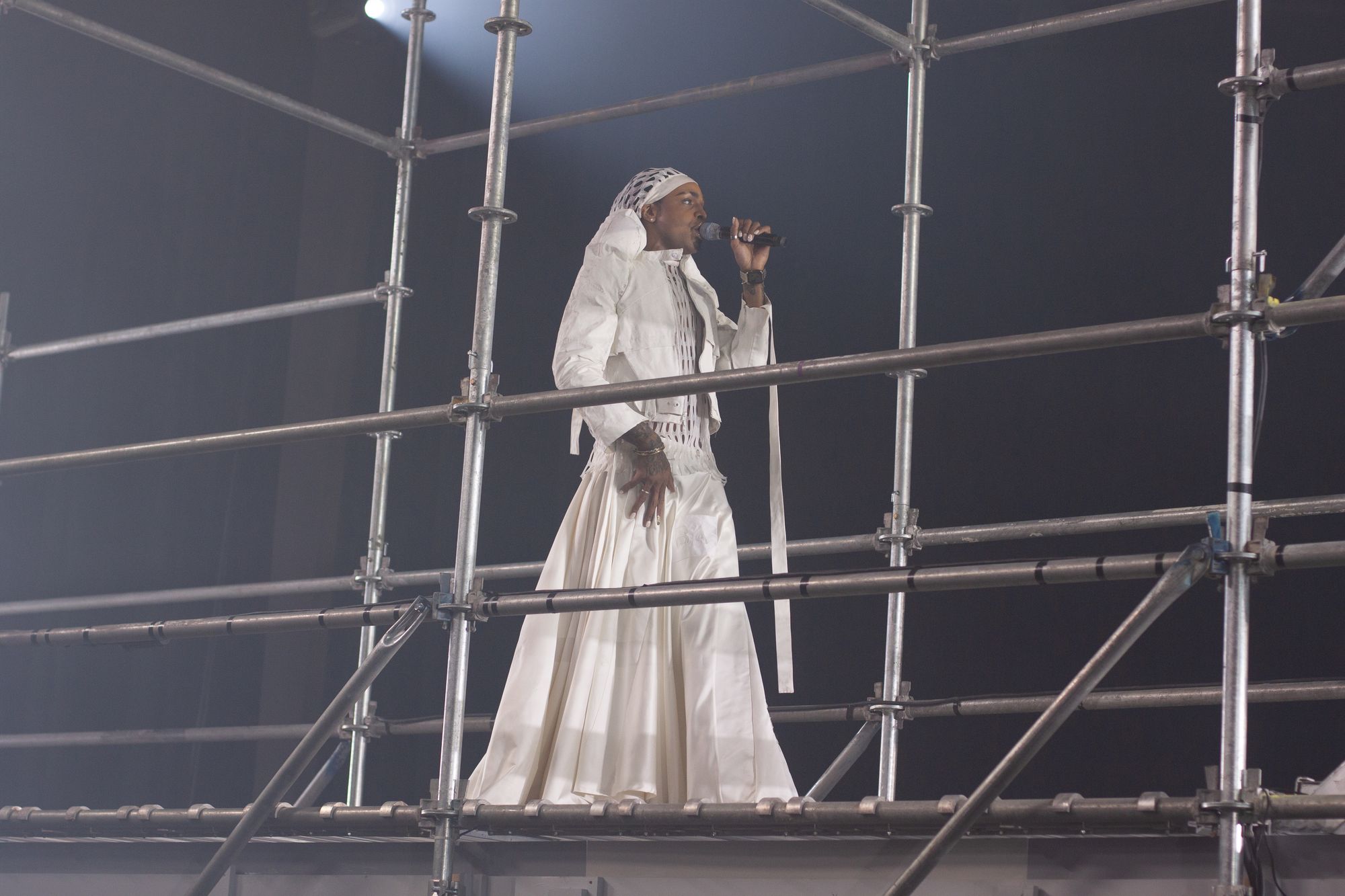

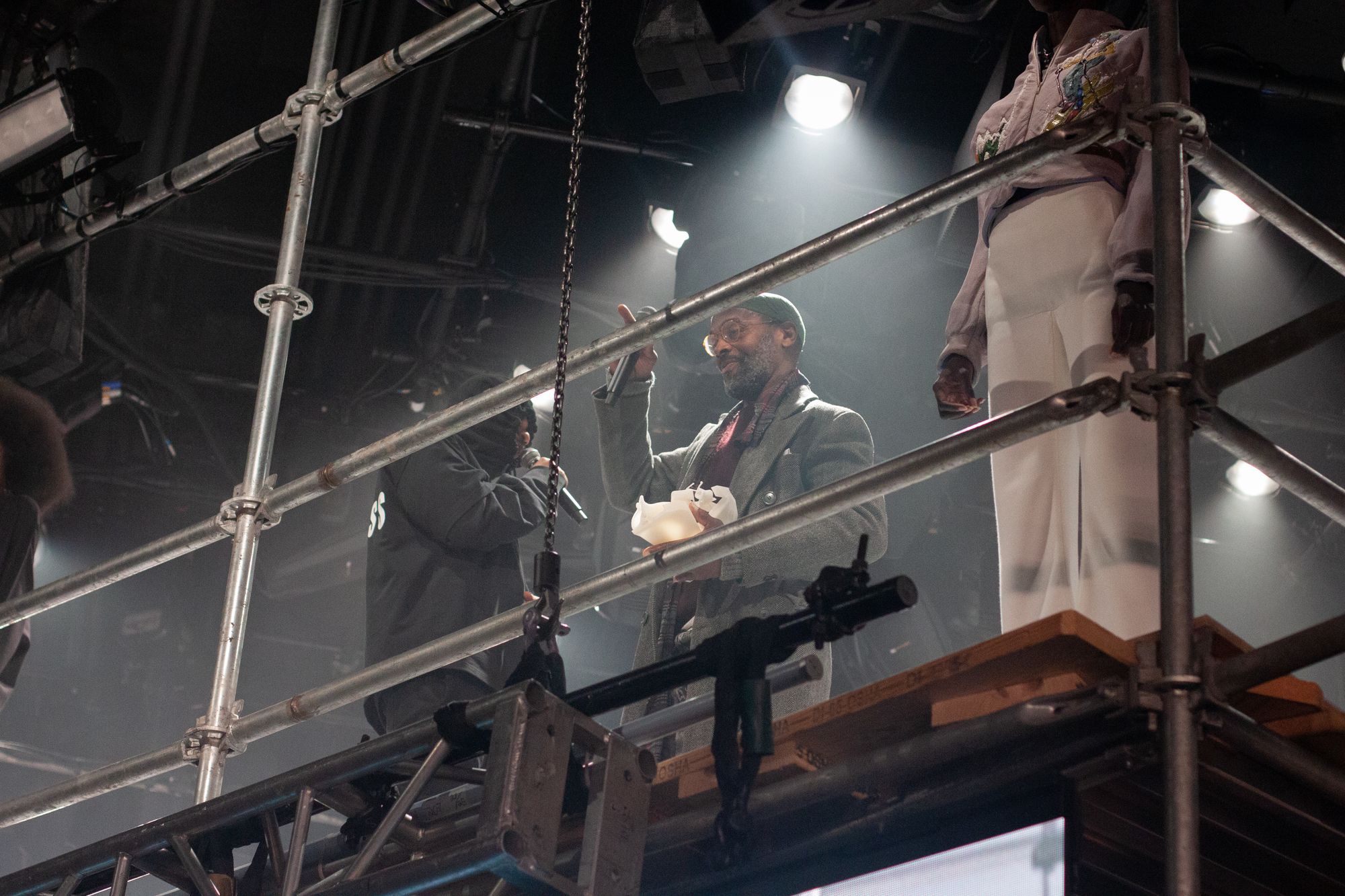

HEADLESS was the largest setting yet for Anonymous Club’s expansive ethos. Ian Isiah, Izzy Spears, Deli Girls, and Eartheater performed. Oliver staged a tribute to Andre Walker, the original fashion renegade who turned the lifeblood of 1980s New York City subculture into fashion fodder. Total Freedom, Omar S, and Yves Tumor deejayed, each one transforming The Shed into a different version of a nightclub. Even the fashion that Oliver debuted on the second night had a multimedia element — each crystal-studded, warped look will serve as the cover art to a different song from Wench, Oliver’s ongoing collaboration with Arca.

Ian Isiah performing at Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Shayne Oliver presenting Andre Walker with an award at Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Warmth and elevation aren’t necessarily two concepts that go hand-in-hand, but that’s how Oliver wanted to define the “monolith,” the main piece of set design for the event. In some ways, it was a location-specific update of the Zürich glass ceiling, swapping out the slick all-white platform with raw scaffolding, the perennial accessory of New York’s built environment. The sheer height of the monolith created a vast distance between the crowd and the performers, a very different scale from the days when HBA and GHE20G0TH1K — the club night that Venus X launched back in 2009 — were synonymous with smoke-filled DIY spaces. Oliver wanted to literally put his collaborators up on a pedestal.

The design originally came from the sensory experience of seeing a building surrounded by fog, and slowly realizing that what you see isn’t the whole picture — there’s always more building behind the shroud. “We were in the fog space, and then the monolith is the actual peak of the building. That was the starting point for it, but afterwards it evolved more into what would make sense for the different kinds of performers we had, so it became more geared towards the clique and everyone’s needs.” Oliver says some people loved it while others hated it, even internally. The models had to scale the stairway leading up to the elevated stage before zig-zagging through the crowd, but some insisted they were just going to walk around the structure rather than make their way up the steep incline in heels so elongated and pointy they could double as door stoppers.

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Anonymous Club’s HEADLESS: The Demonstration at The Shed during New York Fashion Week Fall Winter 2022. Photographed by Elvin Tavarez for PIN–UP 32.

Oliver’s goal was to make HEADLESS feel like an open studio — they purposefully didn’t rehearse — and these rough-hewn edges clashed with the black-box art-world conventions of The Shed. “It was fun to play with the boundaries,” he says. “You can’t really escape how much of an institution it is.” This became abundantly clear when Oliver invited the crowd to climb up onto the scaffolding and dance: those who were brave enough to try received a swift dismissal from a towering Shed security guard. “It was kind of a prototype for a club in a way,” continues Oliver. “Hopefully in the future we’ll get to have our own club space.”

Collective space is on Oliver’s mind right now: on the lookout for a new headquarters, he’s considering moving Anonymous Club to a remote location in Brooklyn so as to accommodate high-production-value happenings. “I want to be able to shut the space down when we develop seasons and make it only for events,” he explains. “People keep saying it reminds them of the Factory.” Oliver hadn’t thought of that originally, but now he’s using the Warholian reference as a skeleton to help flesh out the space’s future, “though the Factory only became what it was because the work that came out of it defined it so well,” he concludes. “But it’s not a bad place to start.”