Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

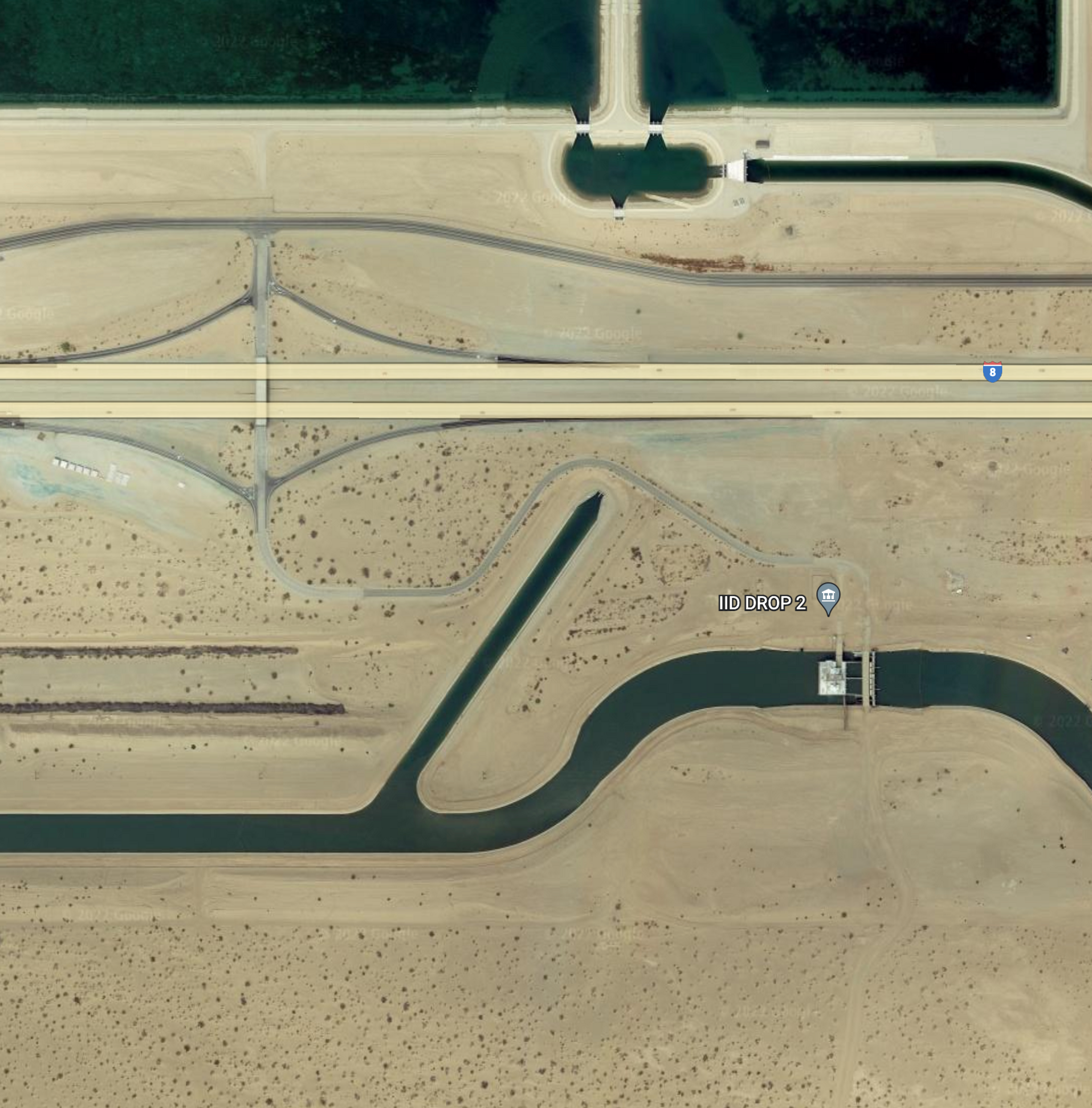

In the early decades of the 20th century, the U.S. government’s Bureau of Reclamation built over 53 miles of canals and 218 miles of laterals, levees, drains, diversion dams, and pumping plants in Yuma County, Arizona, on the Mexican border. Yuma County, the land of the Quechan Tribe since at least 1250 C.E., is part of a highly arid region within the Sonoran Desert, one of the driest in the world, and today produces the vast majority of romaine lettuce consumed in the United States. Every day, farm workers are bussed into the U.S. from their homes in San Luis Río Colorado, Mexico, to pick, chop, wash, and bag romaine lettuce in the fields where it’s grown.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

This lettuce-growing hub only exists because of the All-American Canal (AAC), the crown jewel in the Bureau of Reclamation’s interventions. Tapping into “America’s Nile,” the Colorado River, the 80-mile-long AAC irrigates 630,000 acres of cropland running parallel to the Mexican border. According to NASA, it is the largest irrigation canal in the world, clearly visible in photos from outer space. It’s also “the most dangerous body of water in the U.S.,” according to aquatic expert John Fletemeyer: over 550 drownings have been recorded in its waters since its completion, mostly Mexican migrants attempting to cross the border. The steep concrete sides, the strong undercurrents from hydro pumps, and the absence of safety installations make the AAC extremely hazardous to traverse.

The canal is also the likely origin of another danger: E. coli outbreaks in romaine lettuce. Exploring this bacterial contamination shows us how food transforms, becoming news, trash, and corporate risk and allowing us to see the interconnectivity between one of the most mundane items of produce in the supermarket and the vast infrastructural systems that bring it into being.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration investigated the sources of a particularly widespread romaine recall that seemed to originate in an irrigation canal that was used not only by numerous lettuce farms in Yuma but also a nearby 100,000-head cattle farm. After testing water and soil samples, the FDA hypothesized that fecal matter from the cattle found its way via run-off into the canal’s waters, which in turn contaminated the lettuce fields.

In the public eye, however, it is the migrant workers who are often blamed for contamination: they don’t wash their hands after relieving themselves and/or relieve themselves directly in the field. These entirely baseless claims spread a false narrative to consumers that contamination is primarily an issue of migration, as well as conveniently overlooking the fact that the E. coli variants found in romaine did not originate from the human gut — public concern often favors the well-being of the food product over those whose toil helps to create it. This lays bare not only how disconnected consumers are from the production of even the most banal foods they eat, but also the repercussions of a society that attempts to differentiate itself from its laborers.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

Rarely eaten alone, lettuce exists as a scaffolding for other ingredients and flavors. At Hotel Caesar in Tijuana, the namesake and supposed birthplace of the world-famous Caesar salad, servers drag whole leaves of romaine lettuce through dressing at the bottom of a large serving bowl — undressed lettuce is anathema to the platonic ideal of a salad. Truly the banal of the banal, lettuce does not fill the same conceptual headspace as other foodstuffs, and is only seen in relation to them.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

But through its contamination and subsequent recalls, lettuce is coated not just with fishy salad dressing but with the artifacts of an entire agri-industrial chain of production. The tragic irony of Yuma’s irrigation canals is that Mexican day laborers who cross back and forth over the border work romaine fields fed by irrigation canals that simultaneously kill and prevent passage across that same border. The AAC and its associated infrastructure not only make this arid region capable of sustaining industrial levels of agricultural production, they also operate as devices of border control. Wedged against the U.S. frontier, San Luis Río Colorado occupies a space necessarily separated from the one which it serves, as the laborers in the lettuce fields must return to Mexico every day in buses that tow their own portable toilets, unable to benefit from the wealth of an economy they help grow.

E. coli comes from the gut biomes of animals, and when we consume contaminated romaine lettuce we are ingesting part of a living architecture. Embedded within the contiguous chains of canal to farm to truck to packing plant to supermarket to fridge is a secondary chain of biological makeup, tiny bacteria passing through the hands and bodies of multiple actors and species, before ending up in our own stomachs and intestines.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

Courtesy of Google Earth. Curated by Peter Halley.

We entered a symbiotic relationship with this family of bacteria millennia ago (we all have E. coli in our gut), but more virulent strains can enter our bodies through our mouths thanks to the biological consequences of agri-industrialization. Romaine lettuce recalls present an opportunity to understand how our own bodies have become re-territorialized by canals and farms in the rural Southwest. What is the real danger in consuming recalled romaine lettuce? Is it the possibility of getting sick? Or is it directly connecting our gut biome to the organic consequences of migrant worker exploitation, over-farming, and the infrastructures of mass-produced fresh produce?