IN TRANSIT: A VISIT TO THE OSLO ARCHITECTURE TRIENNALE

When economies slow down or crash, building is always the first sector to be hit. And when economies enter a prolonged recession, it’s a whole generation of architecture students who find themselves unable to do what they were supposedly trained to do — build buildings. But architecture graduates are a resourceful bunch, and many of them will channel their energies into related work. We saw it with 1970s Italy — all that paper architecture and avant-garde ideas à la Ugo La Pietra and co. And indeed Italy more recently has demonstrated architecture graduates’ lateral thinking: when asked by PIN–UP how he got his current role at OMA (see PIN–UP 19), Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli replied, “I think the crisis of architecture in Italy had a lot to do with it. A lot of people there use the tools from their architectural education to do other things: research, photography, installation, performing arts, writing, and so on. So in a way, the schools are really not that specific, which allows people to reinvent themselves in many different domains.” (Rem Koolhaas has described Pestellini Laparelli as “the partner at OMA who works on projects that are somewhere between being a building and not being a building.”) Another country whose architects have been deprived of construction work since the 2008 crash is Spain, and this perhaps accounts for the content of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale, which was overseen by a group of Spanish architects who are also scholars and curators: Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, Ignacio González Galán, Carlos Mínguez Carrasco, Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, and Marina Otero Verzier. The theme they chose was After Belonging, subtitled A Triennale In Residence, On Residence and the Ways We Stay in Transit — in other words the sharing economy, Airbnb, migration, refugees, transit camps and all those other hot topics that dominate not only the headlines but how we live today.

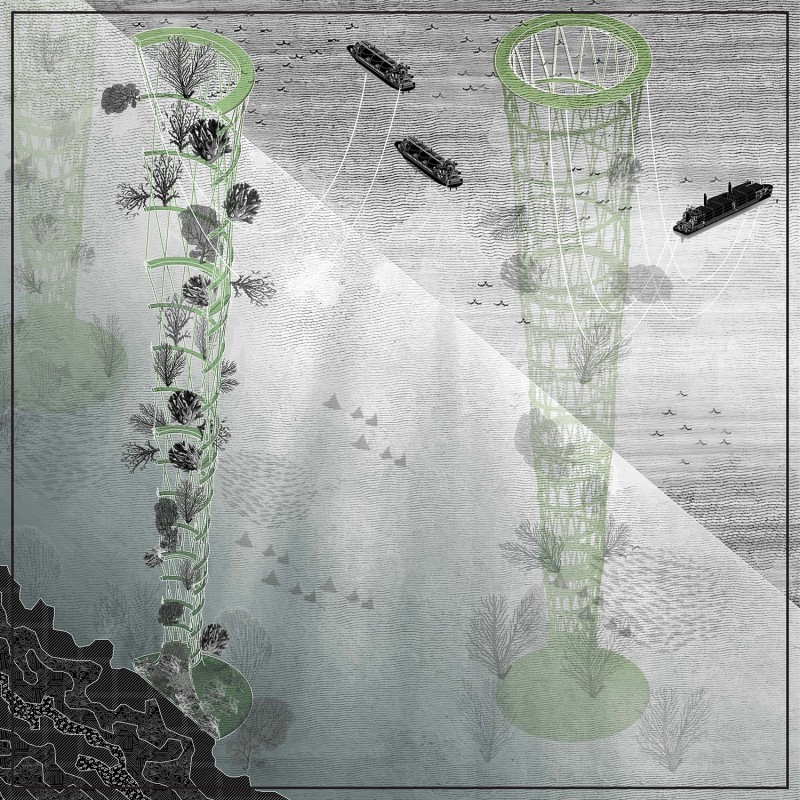

When she set up her private architecture school in Lyon a couple of years back, French architect Odile Decq spoke about how an architecture education, given the broadness of what an architect must know, prepares you to do all sorts of things in life. And the Oslo Triennale is a living demonstration of her theory. Here it is the architect as geographer, the architect as sociologist, the architect as historian, the architect as anthropologist, the architect as statistician, the architect as ethnologist, the architect as conceptual artist, and even the architect as web entrepreneur who are given the floor. Not that there isn’t any design in the classic sense, but you have to look hard for it. One design project that nicely illustrates the Spanish predicament is Home Back Home by Madrid-based firm Enorme. In response to the large number of young Spaniards who are forced not only to return to their parents’ homes after their studies, but to reinhabit their childhood bedrooms, Home Back Home proposes three case studies of old furniture that has been repurposed for returning occupants in a process of customization nicknamed “Ikea hacking” (and indeed the Swedish furniture giant sponsored the project). On quite another scale, Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy of U.S. firm Design Earth proposed nothing less than a series of design solutions to remedy man’s massacre of the oceans in a presentation entitled Pacific Aquarium. Tending towards science fiction and the utopian — a medusa maze to trap, cull, and farm jellyfish; a robot-fish colony to clean up deep-sea-mining plumes; an ocean Parliament of Refugees clearly inspired by Boullée — they were presented via seductive, hatching-rich drawings and rather less interesting Plexiglas models.

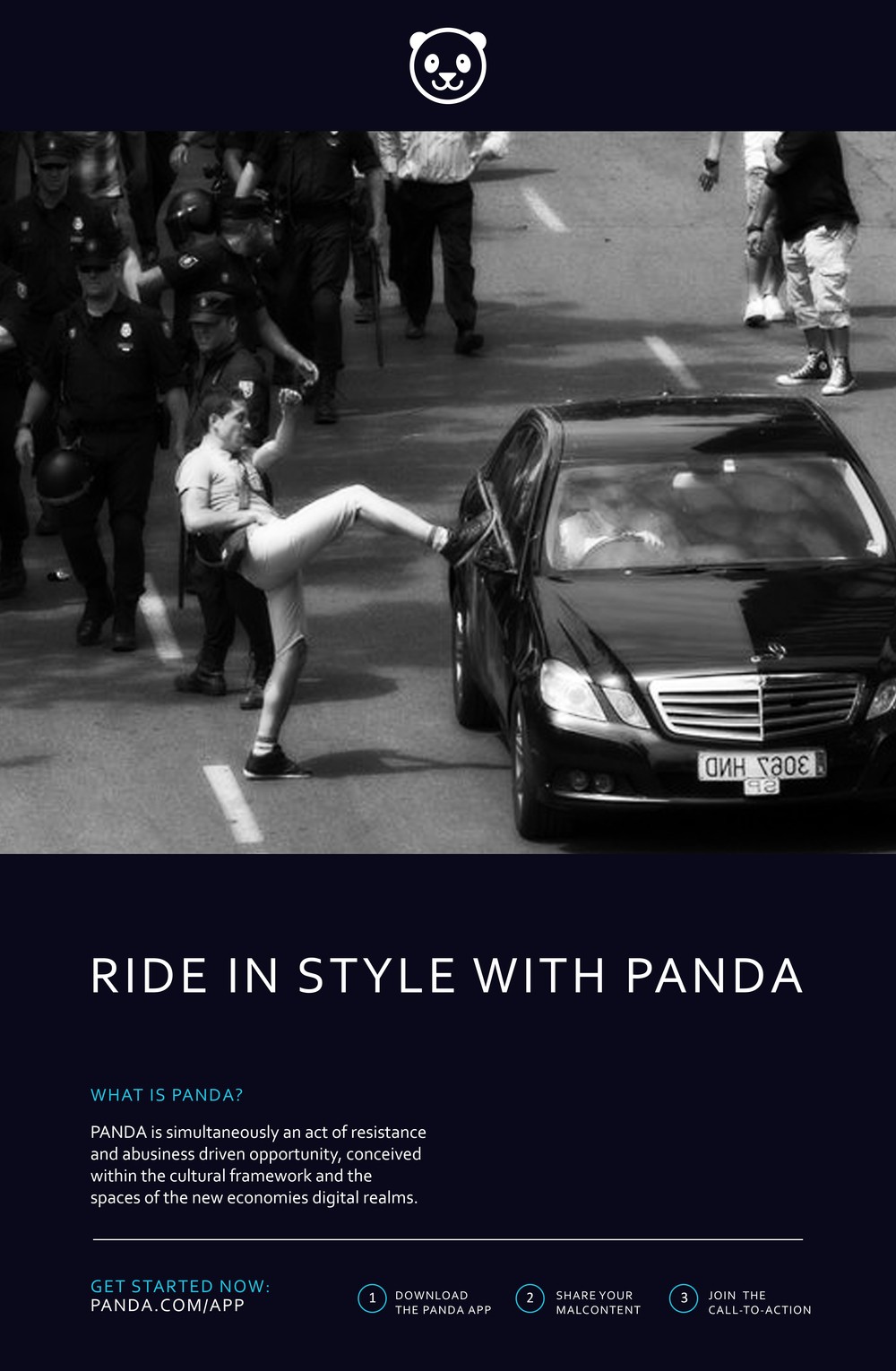

Design in the virtual sense was an obvious choice for the 2016 Triennale’s theme, and there were in fact two apps proposed specially for the event. One is called Cher, and was designed by Caitlin Blanchfield, Jaffer Kolb, Glen Cummings, Farzin Lotfi-Jam, and Leah Meisterlin. The idea is that you can photograph and share absolutely anything you like on the app — your handbag, yourself, or even a bench in the city at a specific time of day. When PINUP spoke to Jaffer Kolb, he wasn’t quite sure what the potential of their creation might lead to, but was pleased to see that it already had a couple-hundred subscribers who were offering everything from “a 32-year-old finger” (“Suggested Use: Being number one, making a point, your turn”; cost unspecified) to an “underwater bike” (“Bicycles are not that exciting on land. Why not try one underwater?”; free) (sign up at http://cher.city). The other app, Panda, is yet to come online, but if it ever does you’ll hear about it pretty fast. Nothing less than “a counter-organizational platform” to allow freelancers exploited by sharing-economy giants (Uber, Airbnb, etc.) to group together and fight back, it was dreamt up by OMA’s Pestellini Laparelli and by Even Westwang and Simen Svale Skogsrud of creative studio Bengler (who designed branding and advertising for the conceptual app). The project “recasts technologies of oppression into a machinery of individual empowerment,” say the team. “By providing tools to actively navigate the turmoils of new digital regimes, Panda fosters a new sense of belonging and purpose.” For Pestellini Laparelli, it’s “at once an act of resistance and a business opportunity,” the idea being that those running the platform could themselves make money from it.

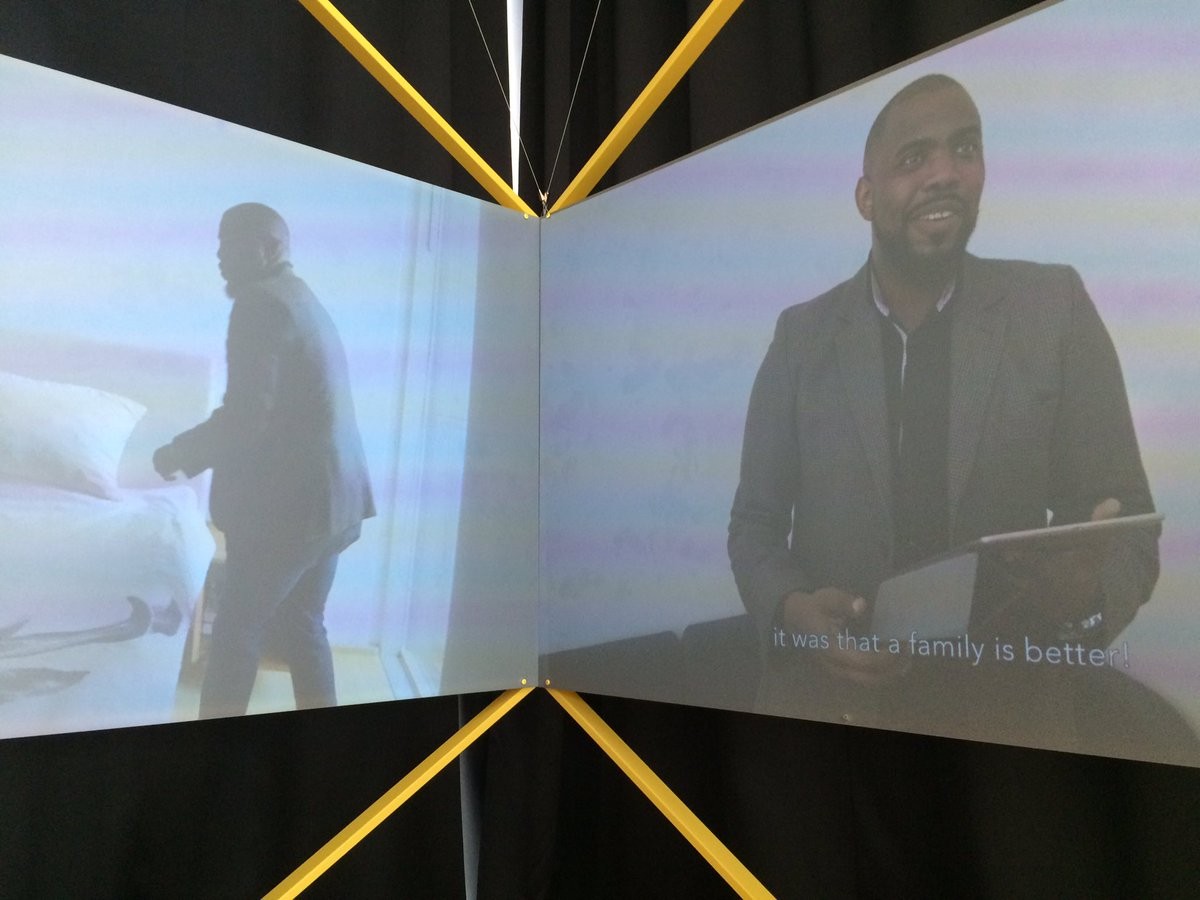

Making money is also the major theme in what are the two stand-out contributions to the Oslo Triennale. And both are films: Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine’s Selling Dreams, and Andrés Jaque’s Pornified Homes. Bêka and Lemoine’s short shows us Copenhagen resident Mark being interviewed in a hotel room that he’s just booked for the night. It turns out that Mark doesn’t have a home anymore, preferring to seek out last-minute deals in a city where the hotel-room offer is apparently such that hoteliers can never fill them all. But that doesn’t mean he’s lost all relationship to the notion of home, for Mark now rents out six apartments to short-term renters, stage managing the interiors with invented host inhabitants. Among his fictional landlords are a gay couple, a lonely artist, and a perfectly blond and white Danish family (Mark is black), and each property is carefully filled with the objects and photos they might possess. Selling Dreams is in fact a diptych, for as we watch Mark talking on the right, we also see a loop sequence of him on the left making an inspection tour of one of the properties, straightening up a picture here, rearranging a vase there, and so on. At the Oslo opening, a crowd gathered to watch this compelling fable — worthy of Georges Perec and combining elements of Elmgreen & Dragset, India Mahdavi’s APT nightclub (see PIN–UP 20), and Tom McCarthy’s novel Remainder — which opens with Mark’s lengthy prologue about how his wife’s displaced knickers gave rise to the whole thing. Some of those present at the opening wondered whether Bêka and Lemoine weren’t having the last laugh by using an actor performing a script…

Andrés Jaque, in contrast, is upfront about his narrative mechanisms, using a very elaborate scripted voiceover to weave together a tale of giant waterlilies and Brazilian rent boys. Pornified Homes begins with the biology of Victoria amazonica, which was brought to Britain from its native Brazil in the 1830s and made to flower on the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth estate in a hothouse specially designed by Joseph Paxton. The flower changes sex, we learn, attracting a certain type of fly while white and female (the fly brings pollen from other flowers), trapping the flies overnight (the flower provides a warm, welcoming space where they can copulate), and then turning pink and male in the morning when it opens up so that the flies buzz off with new pollen on their wings. Jump cut to sleepyboy.com, Britain’s number-one gay-escort site, where we meet two Brazilian rent boys and learn all about their lives in London and what they’ve done to their bodies and their homes. Living in wealthy Kensington or Chelsea is essential, it turns out, to reassure clients. In the tiny flats they can barely afford, Bruno and Rafael have created “a secluded and sexualized backyard architecture of otherness,” as the voiceover has it, capitalizing on their Brazilian exoticism to hoist themselves out of poverty. This is one of the ways that “we stay in transit,” to quote the Triennale’s subtitle, and clearly the plan is that one day Bruno and Rafael will escape their hothouse for something better — just like the founder of sleepyboy.com himself, a former rent boy who is now a dotcom millionaire. The story is as old as London, and reminds one of historian Dan Cruikshank’s startling but compelling thesis that the British capital in the 18th century was not only largely driven economically by prostitution, but that the sex trade had a significant impact on building and on the social topography of the city (The Secret History of Georgian London, Random House, 2009). There were no architecture triennales back then to lay bare the mechanisms of vice, real-estate, and construction, but, thanks to Oslo and its ilk, future historians of our era should have an easier time of it.

The Oslo Architecture Triennale runs until November 27 with a whole host of events and talks programmed between now and its close.

Text by Andrew Ayers.