REPARATION HARDWARE: ILANA HARRIS-BABOU’S TAKE ON THE AMERICAN DREAM

Reclaimed wood, heritage chairs, antique buffets — there’s an undoubtedly romantic impulse in decorating space with the resuscitated remnants of a “timeless” past. As a catalogue from upscale furniture showroom Restoration Hardware puts it: “salvaged wood is intrinsically better.” Better to buy brand-new family heirloom that feels like it could’ve been your grandmother’s, even if you can’t name a family member one or two generations back. After all, it’s through our stuff that we let others know who we are. Or who we wish we were.

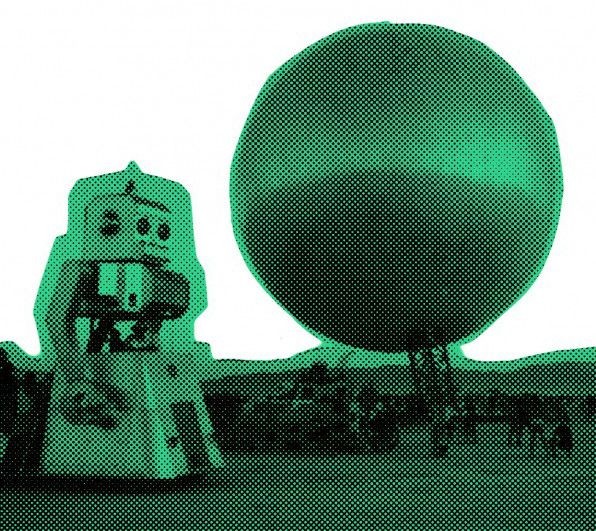

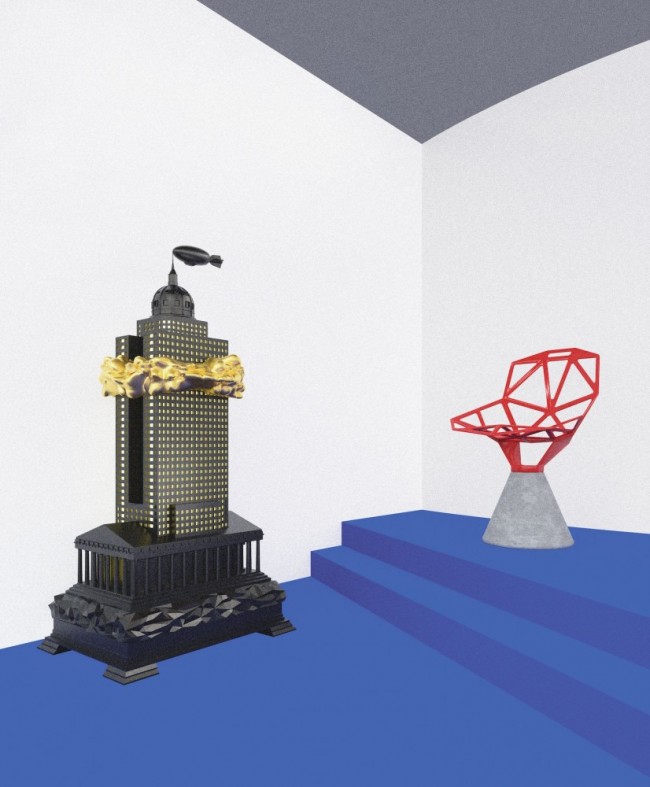

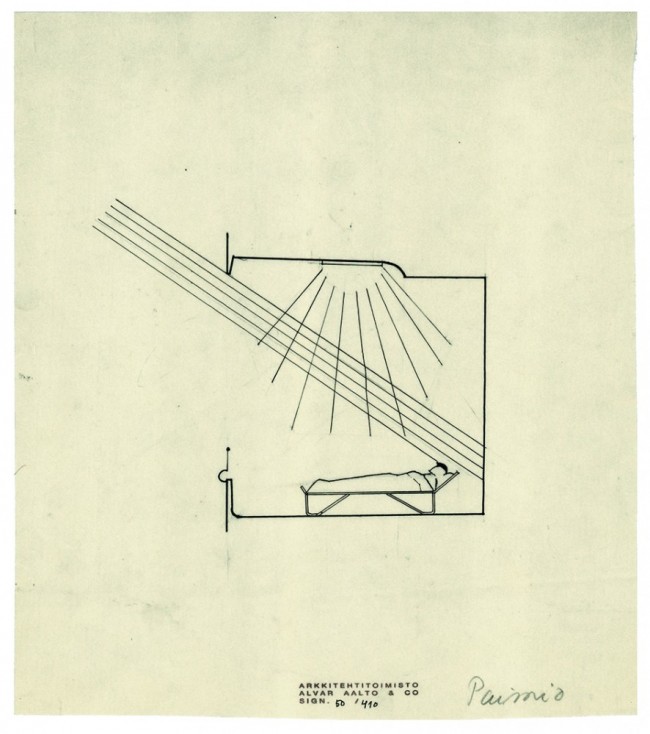

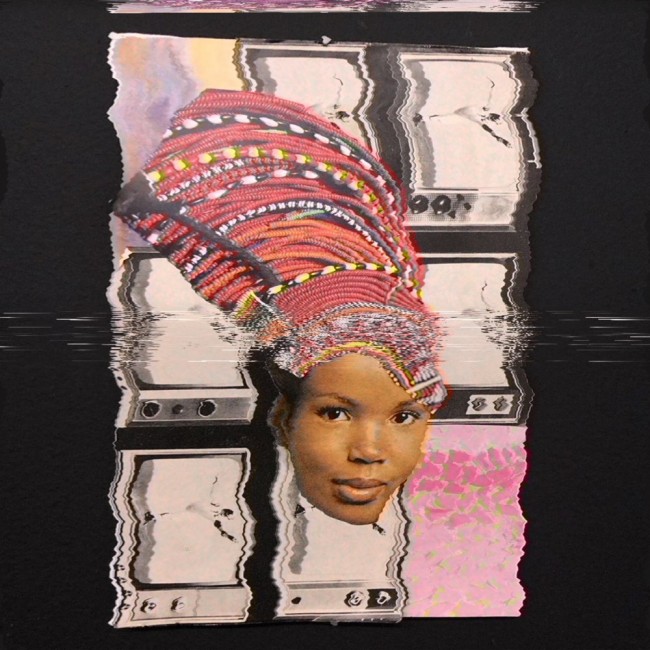

This is the proposal set forth on the screen you see immediately upon walking into the New York gallery Larrie. The video, which is part of artist Ilana Harris-Babou’s current show Reparation Hardware, promises to let you take the past into your own home, tastefully, of course. It promises to “corral time.” Most radically, it promises to make things right. Conceived as a wryly comic advertisement and designer profile (it originally appeared on DIS.art), this project is Ilana Harris-Babou’s answer to the nostalgic desires of aspirational design stores. Visible just beyond the flat-screen displaying the video which shares the exhibition’s title are what could be taken as Reparation Hardware’s various offerings: lamps, tools, coat hangers, and more, rendered in glazed ceramic. Even the wood tables and the gallery’s planter were made by Harris-Babou. “Their liberation was handcrafted,” chirps Harris-Babou in the style of a furniture maker turned cheerful marketing impresario. And handcrafted are also her works, which reveal their deft, intimate manufacture as much as they evince the deadpan satire and absurdity of the project as a whole. After all, what good is a ceramic rope? What nail can you hit with a clay hammer?

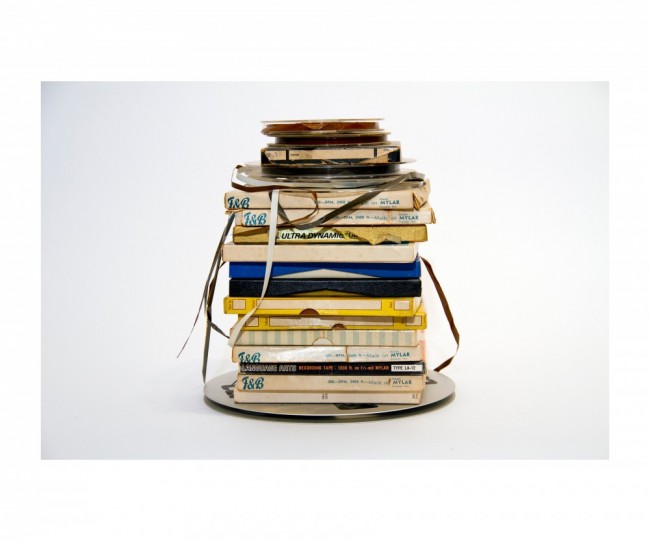

The tension between fragility and solidity, use and uselessness limns the parodic indeterminacy and historical muddiness that these “products” make their object. The hammers rendered in ceramic — either on their own or as stacked together making a lamp — are rendered entirely and ironically useless. Even with a real hammer in hand in the “Reparations Hardware” video, Harris-Babou misses, or doesn’t even try to hit, the nails placed haphazardly in decaying planks. Her notepad is just covered in illegible scribbles. The purpose promised in the products she’s manufactured is itself a hilarious impossibility. These tools go nowhere. Her untitled lamps, perched on tables made of cobbled-together planks of varying sizes and origins, are hodgepodges made whole — precarious layers of creams and pinks and ochres that seem to be melting into one another, barely and fantastically coalescing into recognizable products, “repared” rather than restored. The smoothed over clay rings wrap themselves about black plastic hardware, an elegant disjuncture. One particularly salient lamp is made of a mass squares upon squares of stoneware hammers. If, as the myth of consumer capitalism would have it, the objects we choose to surround ourselves with are our attempts at self-definition, if they are us trying to ensure others of our success, then what are the would-be purchasers of the “products” of Reparations Hardware trying to communicate? These are homewares that distill the inherent contradictions in attempting to reconcile and delineate a particular past by controlling the spaces of the present. They propose a new set of possibilities, even as they lay bare existing failures. They are a new way of rewriting ourselves in the present.

Throughout the show, discourse on sharecropping, land ownership, and other issues are delivered in the same bubbly, sanitized language borrowed from actual Restoration Hardware videos. Harris-Babou’s video Red Sourcebook for example culls upon a 1936 underwriting manual from the Federal Housing Administration that praises “naturally or artificially established barriers” to protect neighborhoods from “adverse influences” such as the “infiltration of…lower-class occupancy and inharmonious racial groups.” These quotes, with all their bureaucratic do-gooder euphemisms, appear on screen as Harris-Babou flips backwards through a Restoration Hardware Outdoor catalogue, dividing the picturesque landscapes with a ruler and a red Sharpie — literally redlining them. Using the same intellectual tools as the rest of Reparations Hardware, the racist rhetoric enshrined in U.S. housing law is read through people’s desires and aspirations, unearthing the violence and inequality built into the fundamental beliefs and cravings of American capitalism.

All of the show’s tongue-in-cheek-ness belies the dead seriousness of what Harris-Babou proposes: reparations of centuries of stolen wealth for the tens of millions of black Americans descended from those who were brought to the U.S. as slaves and who continue to be affected by systemic racism that has endured long after abolition. In her work Harris-Babou often relies on what she calls “aspirational media;” culling upon media and commercial language we’re used to she takes the “familiar formats and complicate(s) them, making space for failure.” The failure at hand in Reparation Hardware is the failure that is so-called American Dream, its mythic promise not only a promise built on the back of genocide and slavery, but by virtue of being a promise an act of perpetual deferral. It exists suspended between an ideal, a necessarily unattainable future, and a romantic never existing past that begs us to ask: what of the present?

In Reparation Hardware Harris-Babou highlights how reparations boldly acknowledge this intrinsic and sustained failure. In an inversion of the work of reclaiming furniture, reparations take the present and make it rusty again. This strange refurbishing is a “chance to make things right” by exposing the cracks and fissures and rot that were always already there. From these unresolved and undone surfaces Harris-Babou creates the space to propose a real, revolutionary future, a new hasn’t-happened-yet. Restoration, in Harris-Babou’s terms, makes sleek the reality of the past and the damages of time. Reparations take the worked-over and sanded down myth of the American Dream and make it again rusty and worn. Built on oppression and exploitation, the reality of the United States cannot continue to be smoothed and stained over; its legacy bears marks into the present that must be repaired and repaid to be reclaimed. Restoration Hardware promises you a chance to buy a new you. Reparation Hardware offers you a chance to buy a new dream.

Text by Drew Zeiba. Video courtesy of DIS.

All images are installation views of Ilana Harris-Babou: Reparation Hardware, 2018, at Larrie, New York. Photos courtesy of Jackie Furtado and Larrie.