LIFE CYCLE: A Coming of Age via Fashion

Leaving America for Europe at the age of 21, on the precipice of full adulthood, was a distinct rupture in my sheltered existence. Not only was I confronted with a variety of new and unusual phenomena — from universal healthcare and free education to income-tax levels over 50 percent — but I also had to question my assumptions, including about what one wears to go out at night. I was born in 1985, four years after Britney Spears, and, as a teenager growing up in the suburbs of Washington D.C., every Halloween, school dance, and underage club visit had essentially been conducted in homage to her, a series of rehearsals for my fruition as a young woman in a secular and liberal society.

Cycling shorts: the interlocking of art, fashion, and body culture.

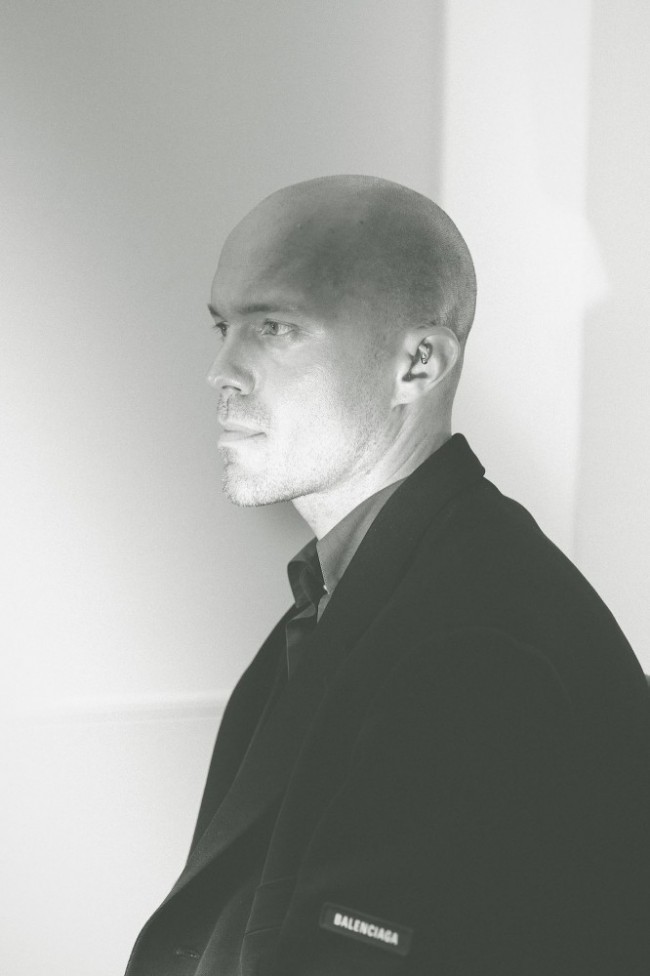

As I moved from college in Charlottesville, Virginia, to Zürich, then to east London, and finally to Copenhagen’s Vesterbro, I understood how unnatural my look would appear to my European peers and how inconvenient it would be to me. It was hardly sexy to look uncomfortable or out of place, which I would have been in high heels — especially when the night was spent sitting on the sidewalk, drinking supermarket beer, and walking home in the full morning sun. Eventually I developed a uniform that seemed to work reasonably well amidst all the various forces at play, something between “Can I bike in this?” and “Will anybody fancy me?”

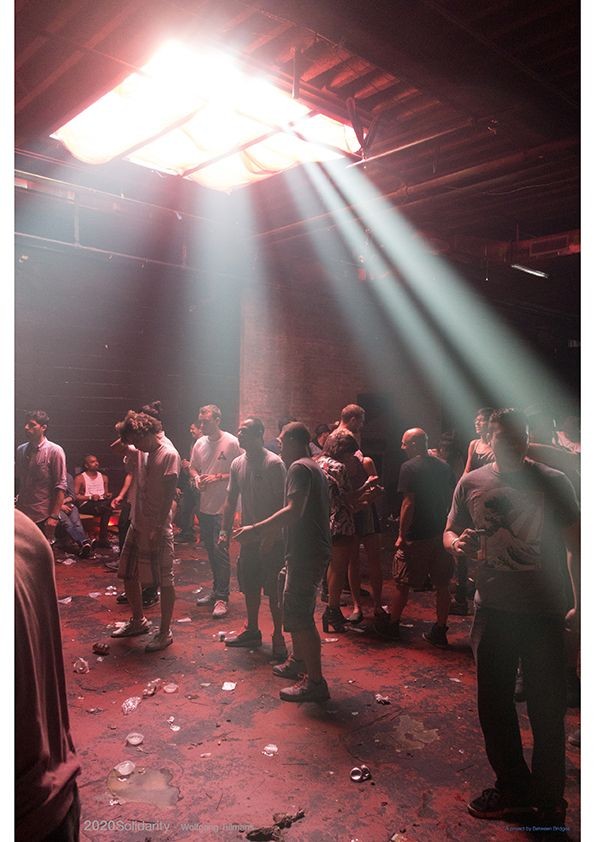

At some point in the past few years, however, a few seismic shifts took place. First, I turned 30. Second, skinny jeans and high-heeled boots became mom-wear. Third, sexual and gender fluidity went much more mainstream (caveat #1: in the places where I have been privileged to reside). Fourth, the nightlife landscape changed. Previously, after about 2:00 or 3:00 am, one had to resort to camp gay clubs to stay out, but now shadowy techno marathons à la Berghain, which once made Berlin famous among the easyJet set, can be found in most European cities. As a result, going to a club feels like wandering between the aisles of H&M basics, Foot Locker, and Fruit of the Loom — 100-percent cotton, as far as the eye can see. I understand people’s desire to be comfortable when dancing nonstop for eight hours or more. I also recognize the regressiveness in reifying the highly commodified stereotypes of exaggerated femininity as uniforms for going “out out.” It’s also pretty pointless: when our most intimate moments from “woke up like this” to the insomnia of the early hours are shared with thousands of followers on social media, the ritualistic self-transformation that used to mark the transition between day and night has lost its illusory potential.

Billy Bultheel and Franziska Aigner in Anne Imhof’s Faust, 2017. German Pavilion, 57th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia © Photo Nadine Fraczkowski, courtesy: German Pavilion 2017 and the artist.

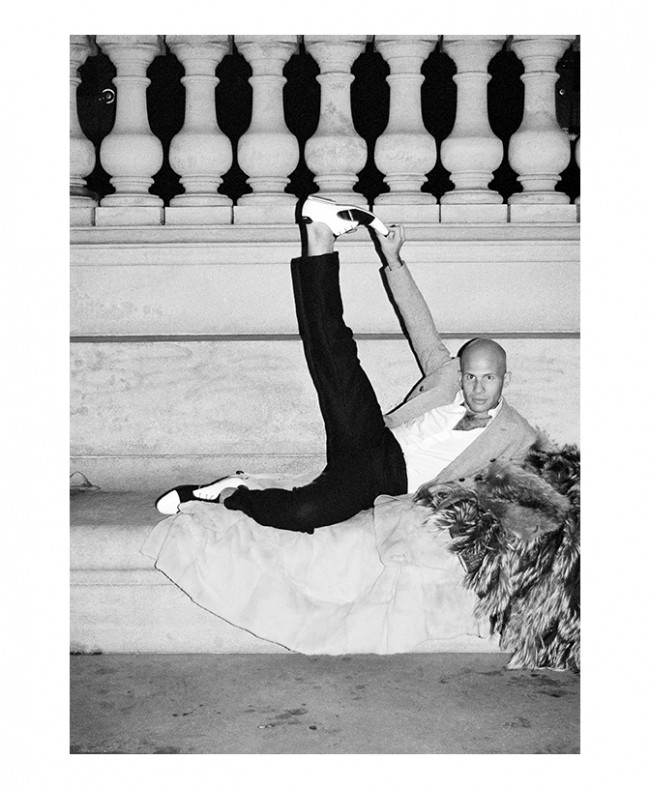

I've been trying to find my place within this new sartorial landscape, but I still can’t help feeling slightly uncomfortable dressing comfortably in a place that sells cocktails. Until a few years ago, you could only wear sweatpants to clubs if they were by Rick Owens or Damir Doma and you looked convincingly avant-garde. Now, athleisure has its own Wikipedia page, including detailed coverage of market shares. A version of athleisure also featured prominently at the 2017 Venice Art Biennale, where the artist Anne Imhof was awarded the Golden Lion for her operatic piece Faust in the German Pavilion. Amidst a forbidding installation complete with barking Rottweilers, her performers writhed around each other, sang, and stared moodily at spectators from their perches on chain-link fences and glass platforms (caveat #2: I didn’t actually see it in person). And yet, if this cast of attractive youths — dressed in sneakers and sports socks, Adidas track pants, and shorts embellished with the FC Bayern München logo — was supposed to inhabit a kind of dystopia, they made it look alarmingly desirable, healthy, and aesthetically fashionable.

Over the past few months, I have thought frequently about this performance and its precise interlocking of art, fashion, and body culture, but most importantly when I found myself putting on a pair of bike shorts for the first time in over 20 years, and to go out at that (caveat #3: I wouldn’t even wear bike shorts to the gym). My main dilemma: what bra to wear? I don’t have the “androgynous” body type of Imhof’s dancers, who can head-bang topless for hours on end with no qualms. Still, wearing a sports bra to go out was a step too far. Instead I sought a hybrid form of comfort as a psychological construct of underwire and lace on top, Lycra and Nikes below. Yet, at age 32, when my knees occasionally start to hurt if I pull some aggressive shapes, I know something isn’t quite right. This isn’t a style that goes with mascara and “foundation garments.” For a look based on the notion of comfort, it offers surprisingly little room to hide. It reminded me of Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris is Burning. In it, drag queen Pepper LaBeija reflects on the way the New York City ball scene had changed since the 1960s, as the paradigm of beauty shifted from the elaborate Las Vegas showgirls to the glamour of movie stars and eventually to the elegance and subtlety of runway models. Later, the legendary drag queen Dorian Corey notes the rise of the “femme realness queens,” meaning those “girls” who could pass without a shade of doubt as beautiful cisgender women in broad daylight without any elaborate costumes or makeup. “Usually, it’s a category for young queens,” she says knowingly.

Text by Tamar Shafrir.

Taken from PIN–UP 23, Fall/Winter 2017/18.