RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Walter Hood on New Black Futures

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

When it comes to public space, Walter Hood is one of today’s preeminent thinkers and makers. A professor at the University of California, Berkeley and recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” he has run the Oakland, California-based Hood Design Studio since 1992, producing distinctive landscapes that reimagine how we relate to urban environments and developing masterplans that pay attention to history, ecology, art, and everyday use.

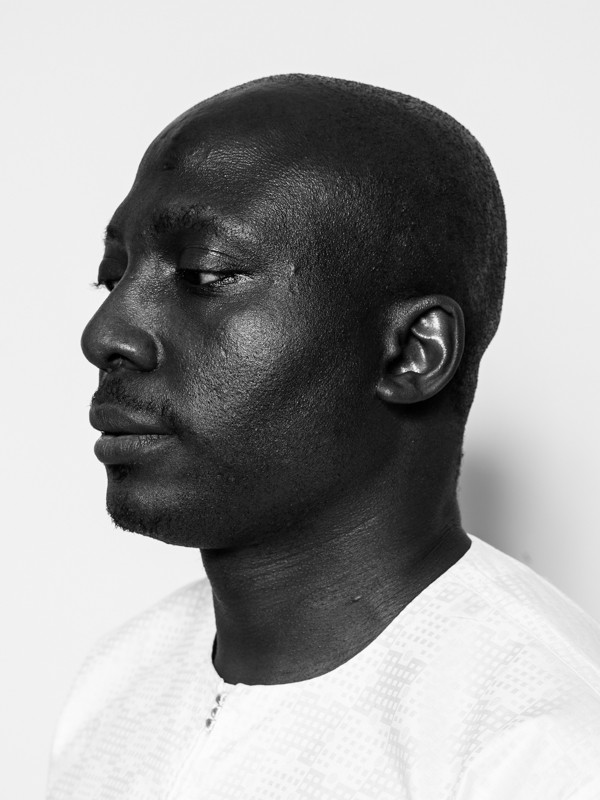

Walter Hood photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture and urban design?

Walter Hood: I’ve always liked making things. I always liked building. When I was in high school, I remember seeing people in a classroom with cloaks on, like white lab coats, standing over a desk. And there was no one in that room that looked like me. I was really, really inclined to go in. I asked the teacher what these people were doing. He said it was called drafting. And I was hooked after that. I really liked this notion that you had to dress up, that you had to prepare. It was during the first few years of integration. A lot of the white kids were being bussed into the city. And again, there were no Black kids in this class, and architecture was completely unknown to me as a profession. And once I walked through that door, it turned out the teacher was Black and he took me under his wing. I actually ended up going to the HBCU (historically Black university or college) that he graduated from. Walking through that door was the thing that changed my life.

How has your practice evolved?

I think going back to that kind of origin provides some insight for my practice today. I walked through this doorway into a world that didn’t look like me, that I was totally unfamiliar with. And it seems that really is part of my practice, in that we’re constantly trying to step through these doors and get people to see the world in a different way. I went on to get degrees in landscape architecture, urban design, and art. My practice is multi-dimensional, it’s much more complete insofar as there are no disciplinary boundaries for me. That goes back to this metaphor of stepping through these doors, stepping through these thresholds to allow me to participate and actually get people to sort of see the world.

It’s interesting that you’re using the metaphor of doors when so often your built projects, by their very nature, don’t have any.

The difference between buildings and landscapes is that with landscapes, you don’t see those thresholds or boundaries, though they do exist and people are impacted by them. I think in the public realm this is what makes it harder to design for difference, because it’s easy to design for sameness. But when you’re designing for differences, it’s a little bit more subtle. Space doesn’t always have an exclamation mark after it. You can be a little bit more gradual in how you take people from A to B and how you get people to actually begin to see things differently. I think landscape as a medium is really complex in that it’s organic and it’s alive. To me, that’s the power, because I can make things look one way today and totally different in 20 years.

Can you describe the project you’re creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

It’s situated here in Oakland, California, and is located on a 1 mile stretch of roadway that pretty much runs north–south for 50 to 60 miles connecting different cities together along the bay. My office has been here the last 20 years, so it’s a site I’ve experienced over time. The project is called Black Tower Black Power, a play on words, but also a kind of exhumation of a cultural history. 10 towers, Black Tower Black Power kind of exhumes the Black Panthers and the Ten-Point Program they developed in Oakland. Watching this landscape transform over the last 20 years, I noticed a couple things. One is that it’s never gotten better — actually it has deteriorated. But I’ve also watched different nonprofits — particularly nonprofits that engage in low-income housing, a lot of social-reform work, some of them through religion — settle on this strip of roadway, and in their more altruistic sort of goals they’ve set out to make the place better. But still it doesn’t get better, so I’ve asked myself why. And the irony is that these nonprofits are there to do positive things, but they have this inability to think of a different future, because the future they know is tied to the past, which is poverty. My thesis is very simple: what if I armed these nonprofits with the Panthers’ Ten-Point Program, which might allow them to see a different future? These programs deal with education, with housing, incarceration, police brutality, militarism. All of these really powerful political actions, which 50 years ago enabled groups of young Black women and men to think of their future. And then if I zoom in on the history of redlining, which has plagued the area, and I look across the red line, which is a boundary, I now see 30-story housing towers going on. Can I empower these nonprofits to build their own 30-story towers? I’m proposing high-rise towers for each of the ten nonprofits and illuminating how they might think of the future in a completely different way. For each of the towers, there’s a narrative, almost like a novella. In order for me to be able dream anew, I had to create a fiction that would allow me to be more speculative.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

To me, it suggests future possibilities. I’ve always found troubling the notion of “reconstruct” as a do-over. The thing with Africans and then African-Americans and now Blacks in this country is that the starting-over point was never inclusive. It was always an additive thing. And I think one of the things I’m really intrigued by in the show is how I can dwell on and think of the future of Black people in this country. I was drawn to these social services and the inability of our politicians and designers to think about a future for groups of people. I look around the world every day and I think there is this kind of blockage and I don’t think we have the means to actually even dream that way. It’s so tied up in the construction of this country that has always been singular. I do think we have to be very prophetic on the one hand, but also we have to be very imaginative to actually get people to buy into this reconstruction. I don’t think it can look the same, smell the same, taste the same. I think we have to somehow reinvigorate the imagination of this country to think about ourselves as becoming something other than what we are.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

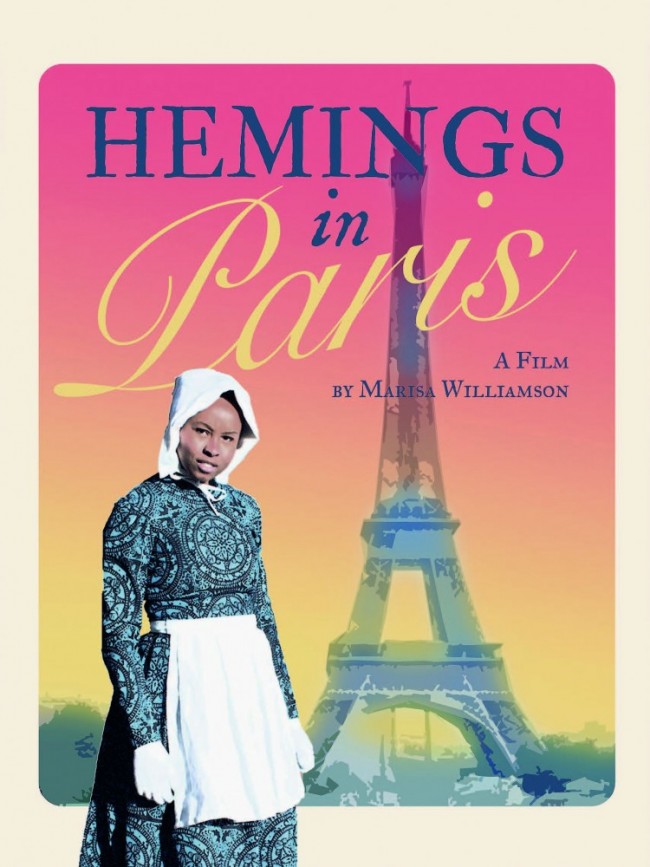

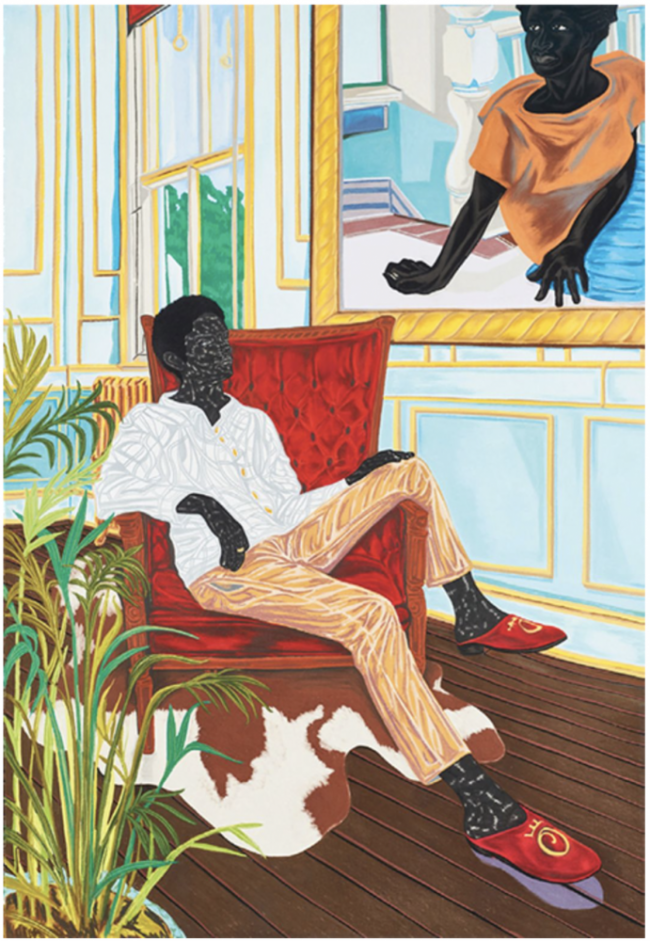

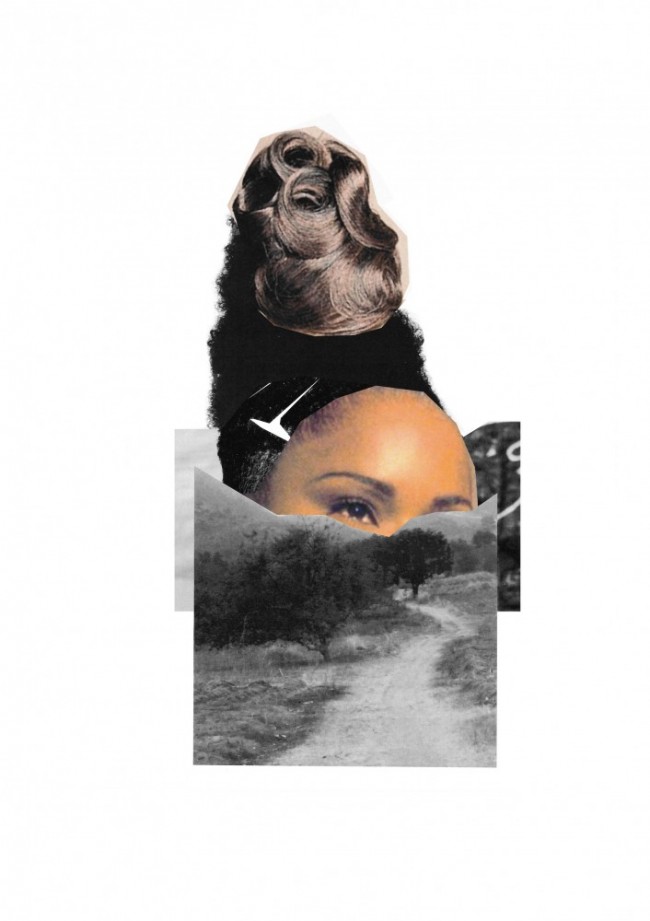

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.