INTERVIEW: Raphael Sperry on Ethics, Design, and the Abolition of Prisons

Should the American Institute of Architects (AIA) explicitly condemn its members for building spaces designed to degrade, torture, or kill? San Francisco-based architect Raphael Sperry thinks so, and in 2013 spearheaded a campaign lobbying the AIA to update its code of ethics to prohibit designing supermax prisons and death-row execution facilities, among others. Together with his colleagues at Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), Sperry was successful in spurring a national conversation around ethics, design, and the prison industrial complex. In the wake of that conversation, the AIA opted not to update its code’s generic language on upholding human rights, but today, with new momentum around social-justice issues, Sperry believes the organization might be more receptive. For PIN–UP, the architect and activist offered insights into what other changes the profession can make to help promote a healthier and more equitable society.

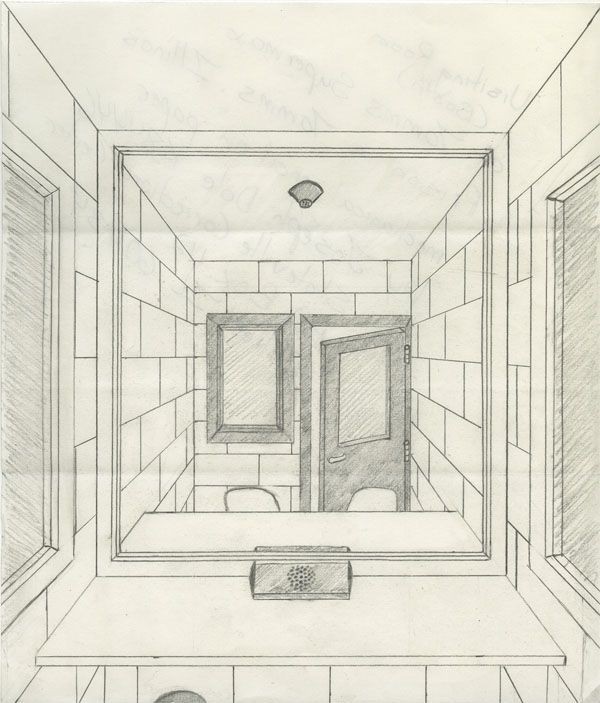

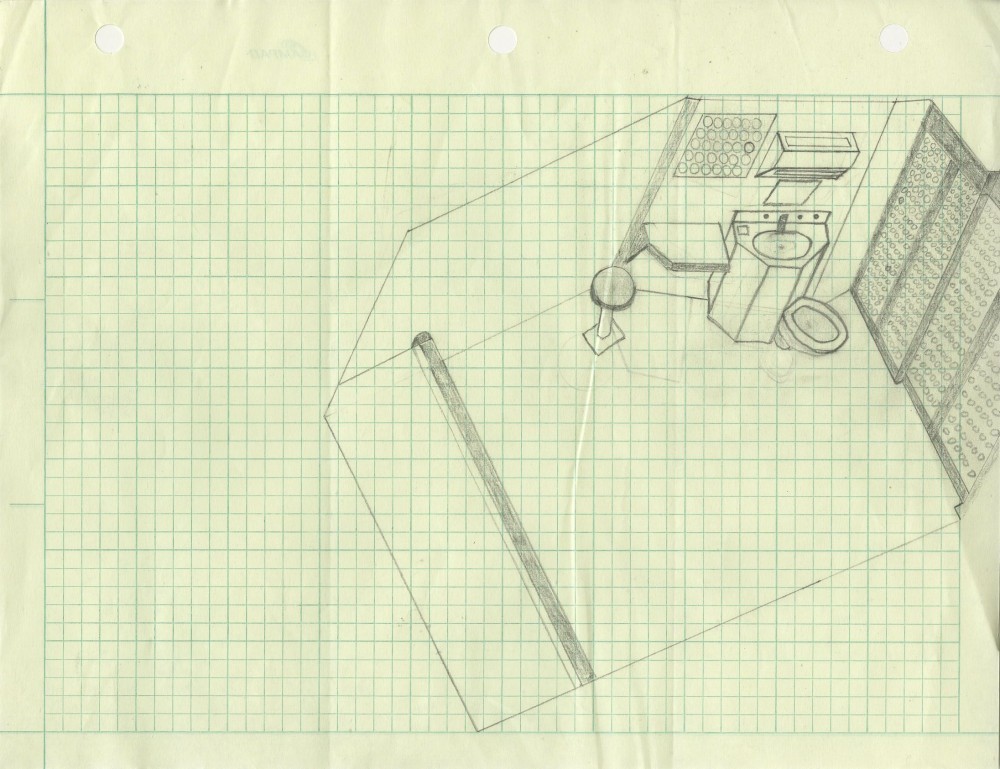

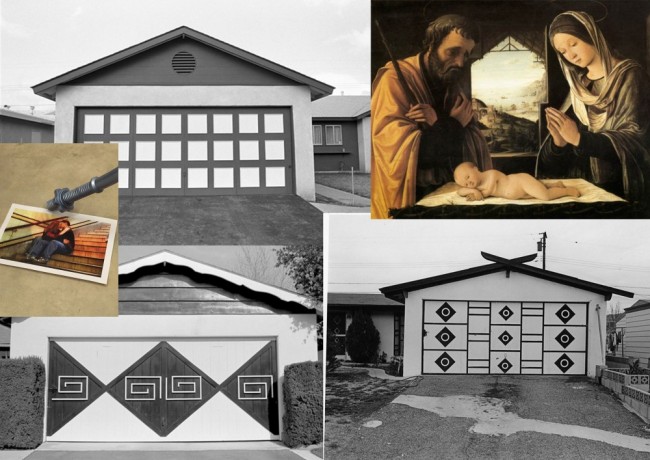

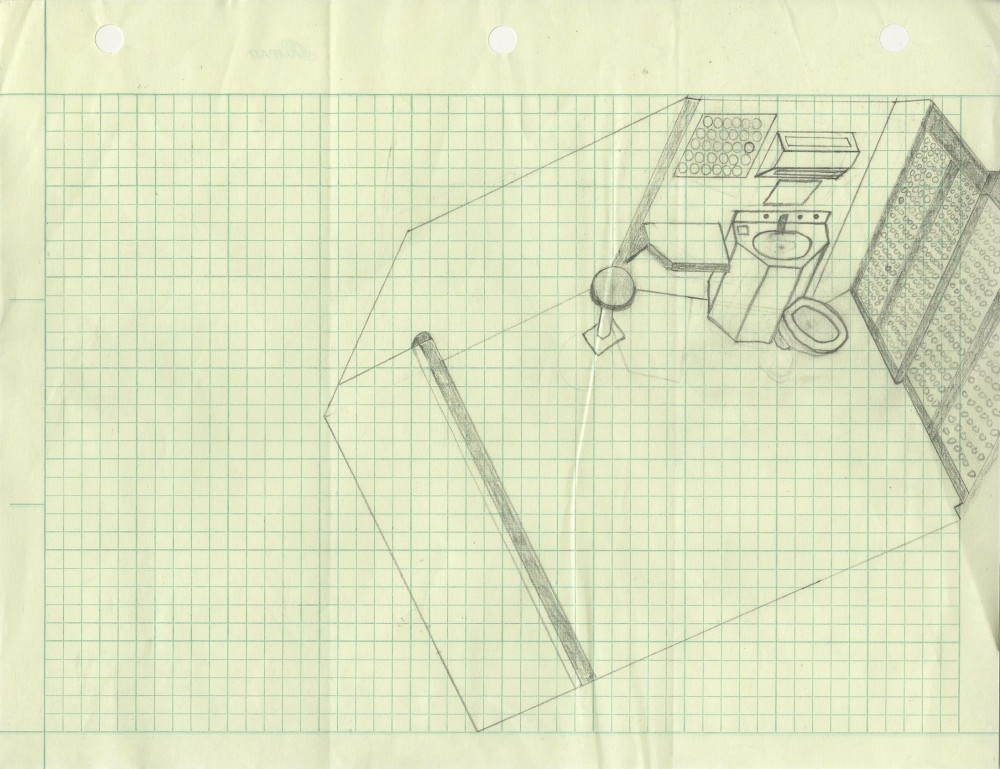

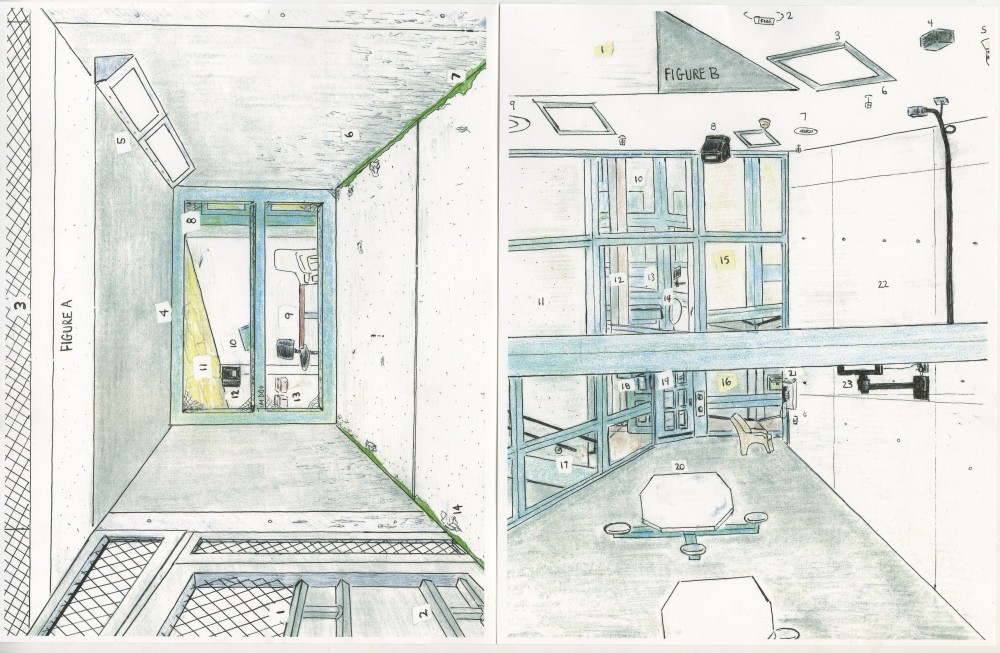

Illustration of a cell at the Arizona State Prison in Florence, Arizona by Patrick Bearup. Taken from the 2014 exhibition Sentenced: Architecture of Human Rights produced by the Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility.

Whitney Mallett: Do you feel we’re living in the midst of a revolutionary moment, and do you think architects and architectural institutions are more receptive right now to some of the structural changes that you’ve been working towards for a while?

Raphael Sperry: I think we’re definitely seeing a moment of opportunity to make major change. Is it a revolutionary moment? We probably won’t know until later, but I think it has that possibility. We at ADPSR have been petitioning the AIA for around six years for what we thought of as a very simple human-rights measure, and we’ve been stonewalled, but that seems like it’s about to change. So that’s a good thing. I think for architecture, when it comes to issues of racism and social justice, there’s an aspect that’s inward-facing — the composition of the profession regarding equity, diversity, and inclusion within the ranks of production —, which means changing the way firms manage themselves. And then there’s a part that’s outward-facing — what the buildings and spaces we design do for society. I’ve seen a lot of folks talking about the history of redlining (the systematic denial of services to residents of certain areas based on their race or ethnicity) as an example of how our profession has contributed to the racial problems we have today. And then the spark that lit the tinderbox this spring was police violence and the whole movement around the murder of George Floyd. Police have been oppressing Black communities ever since there have been police in the United States, as far as I understand it, for the past 150 years or so. Police and prisons are part of the same system of violence. Prisons are extremely violent places. And despite, in some cases, the best intentions of their designers, we have failed to make them safe, and in a sense those that build prisons are somewhat responsible for the violence that goes on in them. In the past you could argue maybe people didn’t realize what they were committing themselves to. But for at least the past 20 years, it’s been pretty apparent how the American prison system works.

-

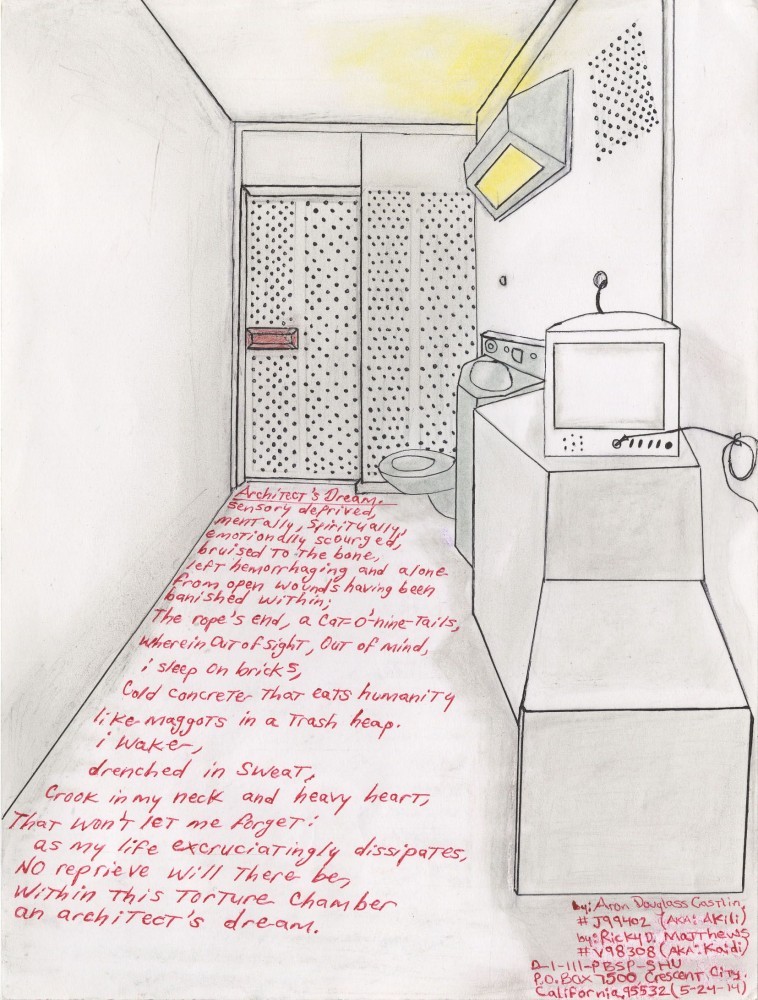

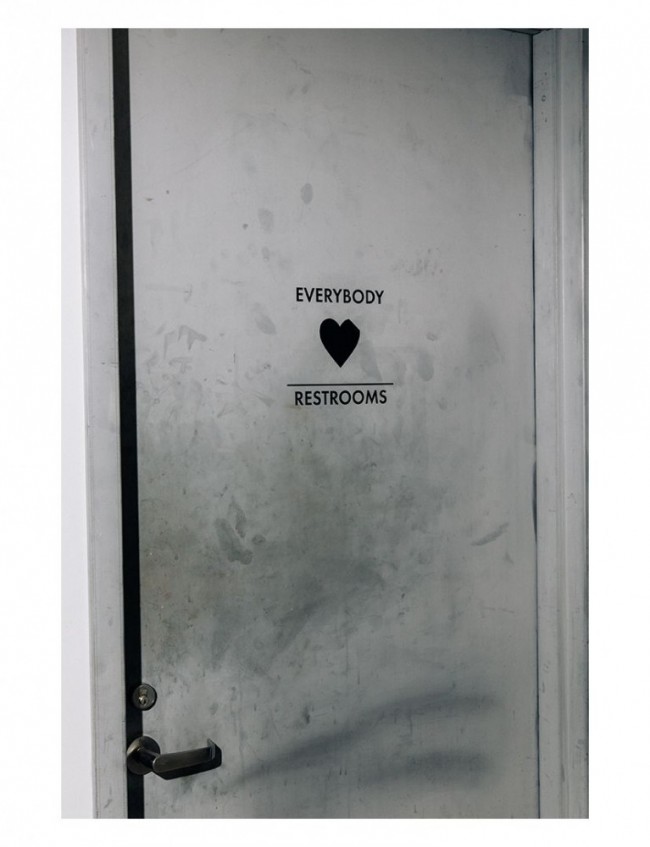

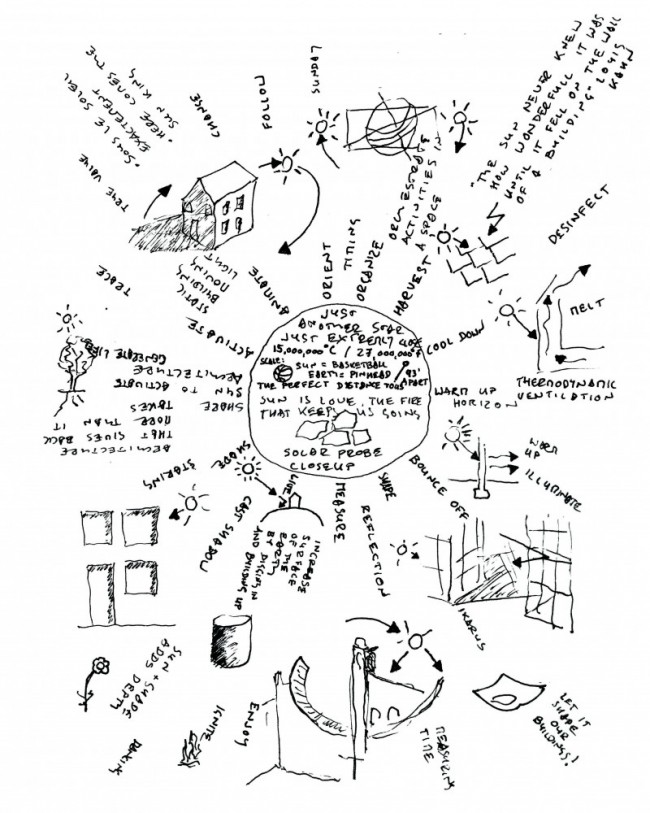

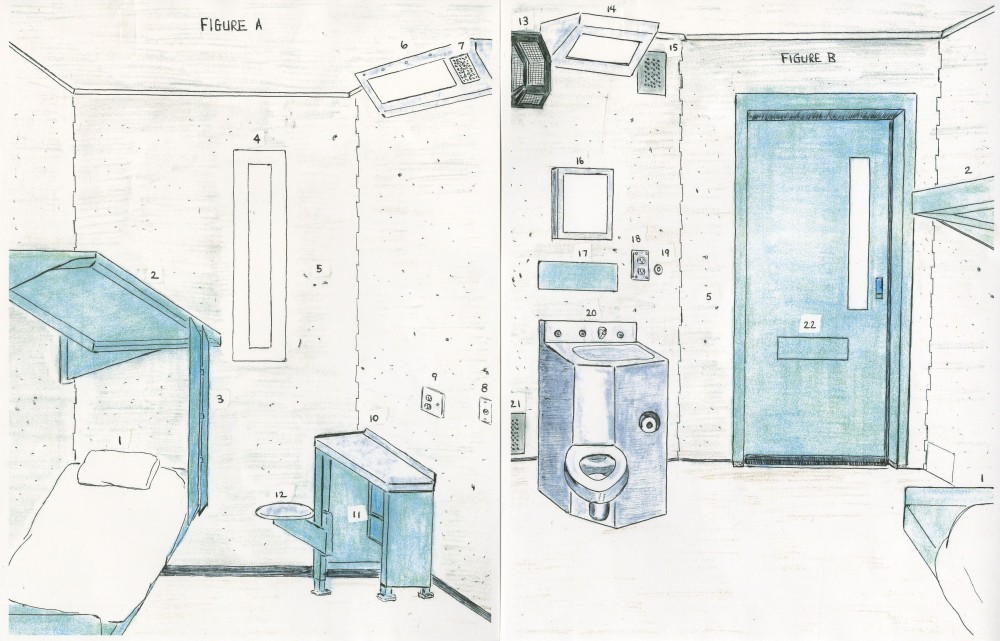

Drawing of a solitary confinement cell made by Carl Hunnicutt while incarcerated. Taken from the 2014 exhibition Sentenced: Architecture of Human Rights produced by the Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility.

-

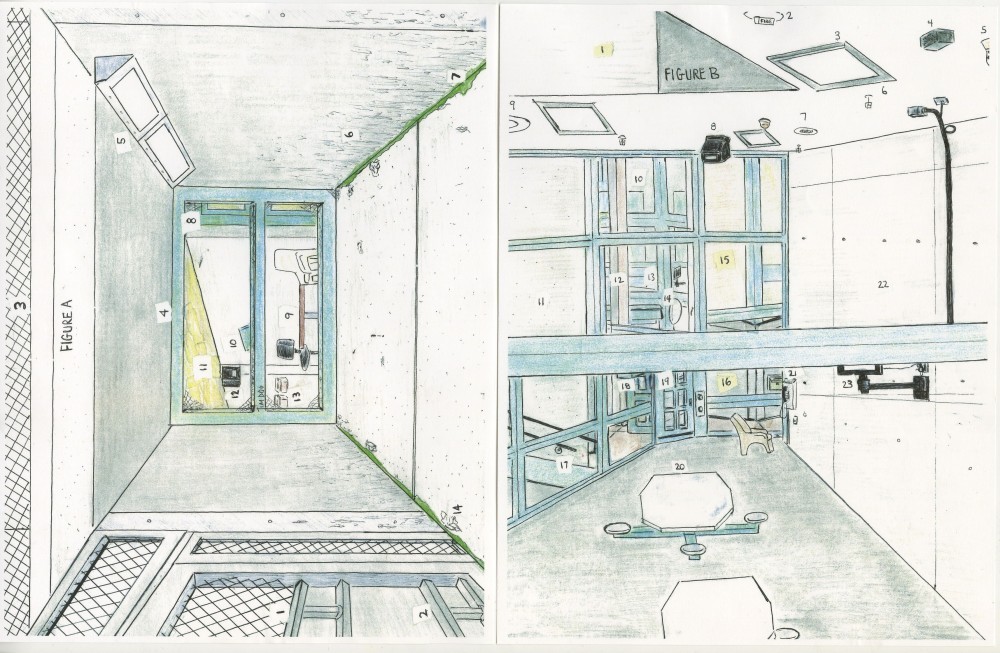

Drawing of a solitary confinement cell made by Carl Hunnicutt while incarcerated. Taken from the 2014 exhibition Sentenced: Architecture of Human Rights produced by the Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility.

You’ve been petitioning for professional organizations to prohibit or condemn the designing of spaces built with an intention to harm. Your writing also interrogates a whole spectrum of cases where design is in the service of oppressive social policy. Architects aren’t off the hook just because they’re not designing death chambers.

When you look overseas, it’s often clearer. You say, “Here’s a government that’s using their police force to oppress their population because they have secret police, or they do raids without warrants, or they jail people for ideological reasons.” If an American architect went to Saudi Arabia and designed a police station, it’d be like, “Why?” Few would dispute that it would further the oppression going on there. If you bring that way of thinking back home and realize that Black communities in the United States view the police in their neighborhoods as an oppressive occupying force, one should ask the same question: “Why build something that’s going to further this oppression?”

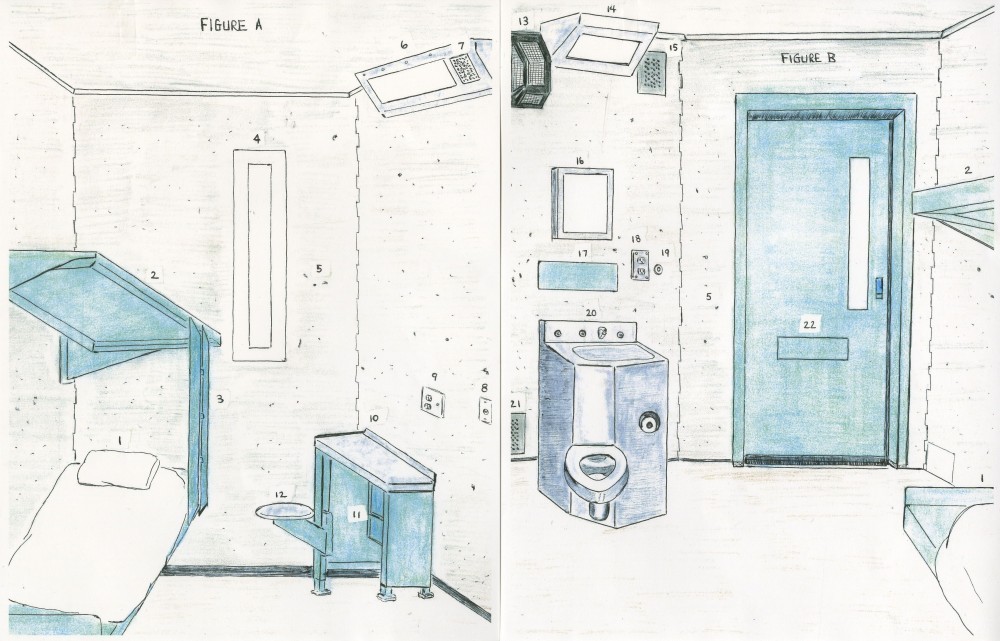

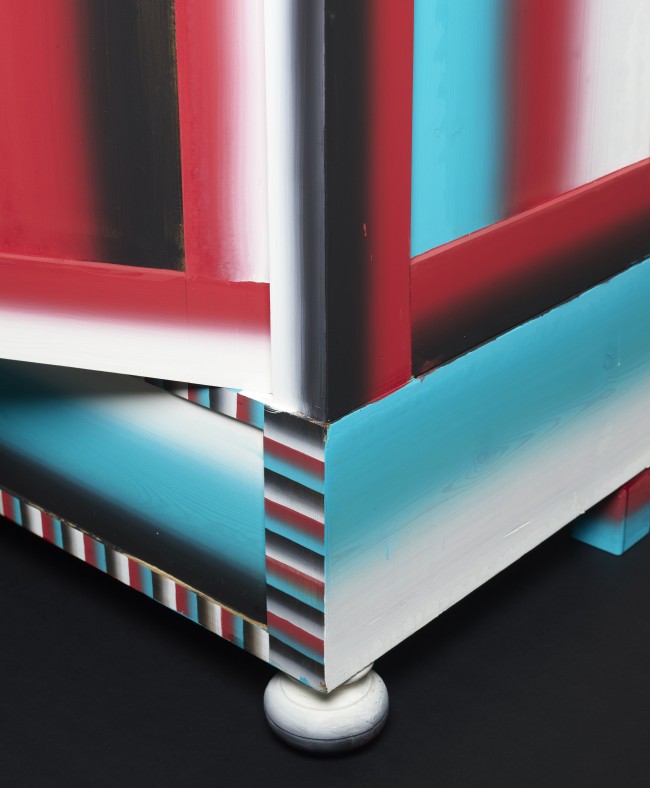

Drawing of a room at Tamms Correctional Center in Illinois by Joseph Dole. Taken from the 2014 exhibition Sentenced: Architecture of Human Rights produced by the Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility.

What about ethical responsibility more broadly, and other ways designers become complicit with the rich and powerful, furthering inequality through their work?

Furthering inequality is not quite the same as furthering direct tools of oppression, but they’re all parts of a society that’s really unjust, and racism has worked its way into everything in America. People realize that now. And conventional architectural practice is part of it. Architects are basically generating new assets. That’s what we do. And almost all of the wealth being generated by them is accruing to white people. It’s not our fault, but that’s how it is, and we’re helping push the wealth gap wider and wider. The wealth inequality between Black families and white families is well-documented. So unless you’re doing anti-racist work to try to end this disparity, you just perpetuate it.

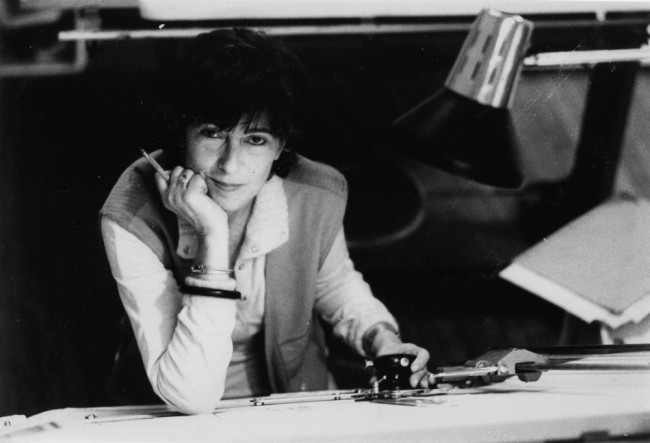

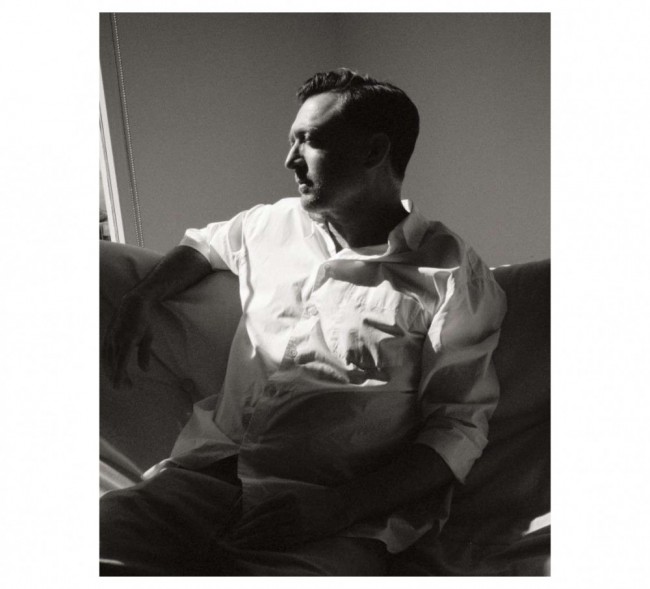

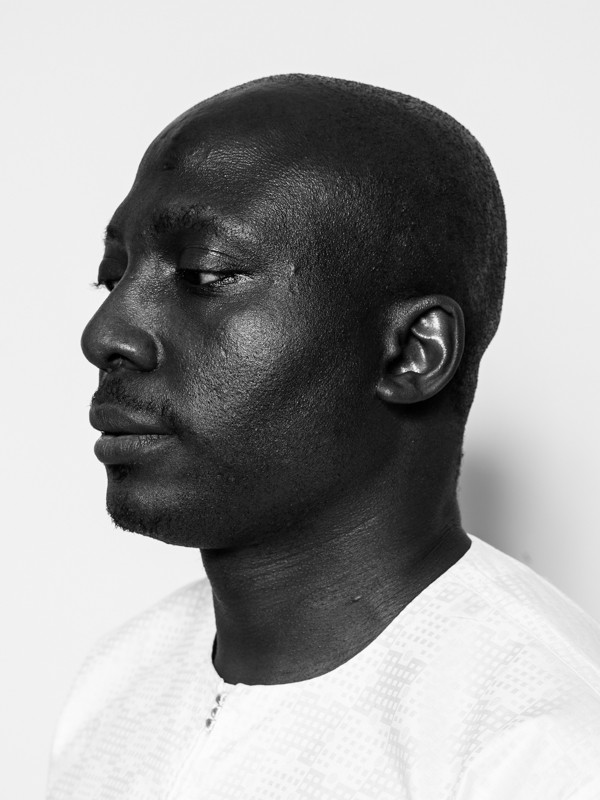

Raphael Sperry photographed in San Francisco by Carlos Chavarría for PIN–UP. Sperry wants the American Institute of Architects to condemn its members designing spaces designed to degrade, torture, or kill.

How can we work towards changing the inequality in the profession itself?

If we want more young talented Black and brown people to become architects, we have to think about what is going to make them want to stay in the profession. Is it going to be designing shopping malls in white neighborhoods? Or working somewhere where they have a say in projects they believe in? Because if you have the skills of an architect, you can make more money working for Hollywood doing CGI. The kind of workplace revolution that I’m interested in is one about the democratic control of companies. Instead of external shareholders or a small group of private partners owning a company, the ultimate level of governance would be an assembly of its workers. Sometimes they call this a worker-owned cooperative, although it doesn’t strictly have to be that, it could be more a worker self-directed enterprise. The key thing is that, in this kind of organization, each person gets one vote. I think under this model there would be more pay equity. If everyone had equal votes, there’d be more transparency around pay information. And I think we would see rapid improvement when it comes to the well-established pattern of women and people of color getting paid less. But I also think that this way of structuring a company would change the kinds of projects a firm takes on. Firms have to stay in business and so compromises might still be made. But right now, these decisions only get made by a small group, and it’s only their values that are reflected. If workers were empowered with more control, they might take on more projects that they believe better serve their communities. It’s not a guarantee, but right now most workers don’t even have that choice.

Interview by Whitney Mallett.

Portrait by Carlos Chavarría.

All drawings taken from the 2014 exhibition Sentenced: Architecture of Human Rights produced by the Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility.

Taken from PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.