INTERVIEW: Curator Maite Borjabad on Designs for Different Futures

From discrete objects to speculative and large-scale systemic proposals, Designs for Different Futures brings together some 80 projects by designers, architects, and artists, exploring ethics and potentialities, alongside new technologies and their social constructions. Co-produced by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, the exhibition considers how we as humans are entangled and our systems for living interconnected. Currently on view at the Walker, the show “is not necessarily about predicting the future,” explains one of its curators, Maite Borjabad López-Pastor of the Art Institute. “We want to allow audiences to understand through design their personal and collective relationships to current complex issues, as well as to notions of the future.” PIN–UP spoke with Borjabad about the sprawling show’s many future-forward provocations, from data and surveillance techniques to bio-design and reproductive technology.

Maite Borjabad photographed by Lawrence Agyei for PIN–UP.

Samantha Ozer: Are there any specific goals that you personally, or as part of a wider curatorial team, have for the exhibition? Is there something that you hope the public takes away from it?

Maite Borjabad: Through researching historical writings on the future, what became clear is that future thinking is a human condition. Acknowledging this was an important milestone, for while the exhibition doesn’t necessarily portray historical examples of future thinking, it recognizes that it is rooted in consideration of humankind. The exhibition is framed around issues situated within our contemporaneity but also transhistorical questions, which, when considered in the context of current technologies take on new meanings. Importantly, design transforms these questions and helps us to identify and evaluate different ways of looking at them. The agents included in this exhibition, the designers, artists, architects, scientists, researchers, scholars, etc. move across diverse temporality scales, from imminent present to far future and channel complex and needed concurrences between design, science and technology along with human needs, desires and fears.

Each of us understand the world in a different way depending on our social and cultural realities. This entangles that the access to resources is asymmetric and so the agency to design and activate desired futures is unevenly distributed. The right to imagine is unevenly distributed.

Phoenix Exoskeleton by Dr. Homayoon Kazerooni and suitX (2011–17). Courtesy of suitX.

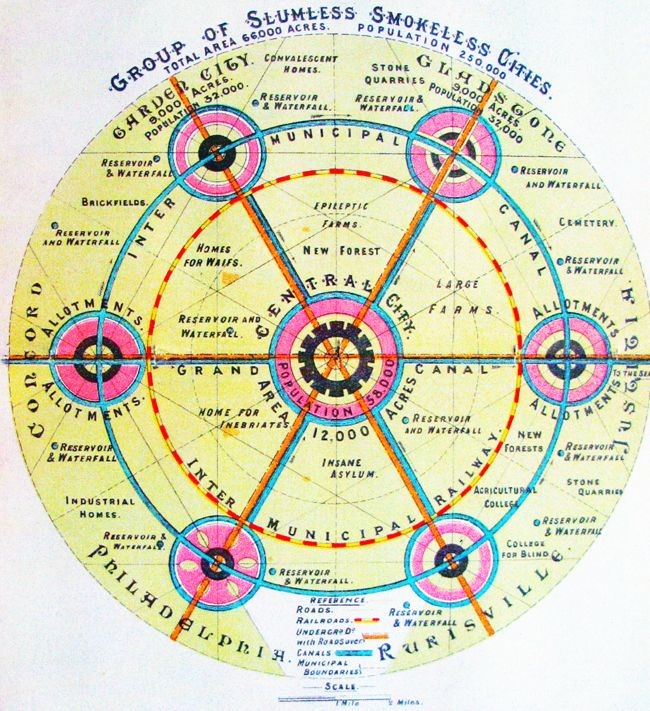

So, another basis for the exhibition is understanding that the future is not a given and that it is not singular. We have been very deliberate in creating pluralities, which were reflected in titling each of the eleven sections, in the exhibition and catalogue, in the plural tense. When we think about the future as multiple, we allow for the emergence of agency. The exhibition is not necessarily about predicting the future, but to allow audiences to understand through design their personal and collective relationships to current complex issues as well as to notions of the future have inherently been disenfranchising. Imagination also plays a powerful role in this process of empowerment. The more time I spend with this research, the more I think this exhibition is really about the present and by gaining agency over it we gain our ability to produce a future for ourselves. Also, by asking how design participates in this process, we can expand the field of design as a discipline and question what is considered design.

Considering the exhibition takes the form of a constellation of themes, do you think the future of design is shifting towards idea-oriented rather than object-oriented projects? Are people more susceptible to revolutionary ideas over objects?

One cannot be without the other. But to me, design itself is a methodology that when partnered with other disciplines, can articulate amazing things. If you understand design as a malleable way to look at the world, then you can look at it through an object or a system, and design provides the tools to communicate and mobilize urgent questions. Considering the global mobility of everything, of humans, of words, of resources, of information, then even when talking about design as an object, the implications of that object are not localized. The issue of scale across the world involves dislocated use of materials, production chains across geographies, multicultural mobilizations of references and highly complex systems. In this way, the design field cannot get stuck considering the object as a stand-alone thing.

-

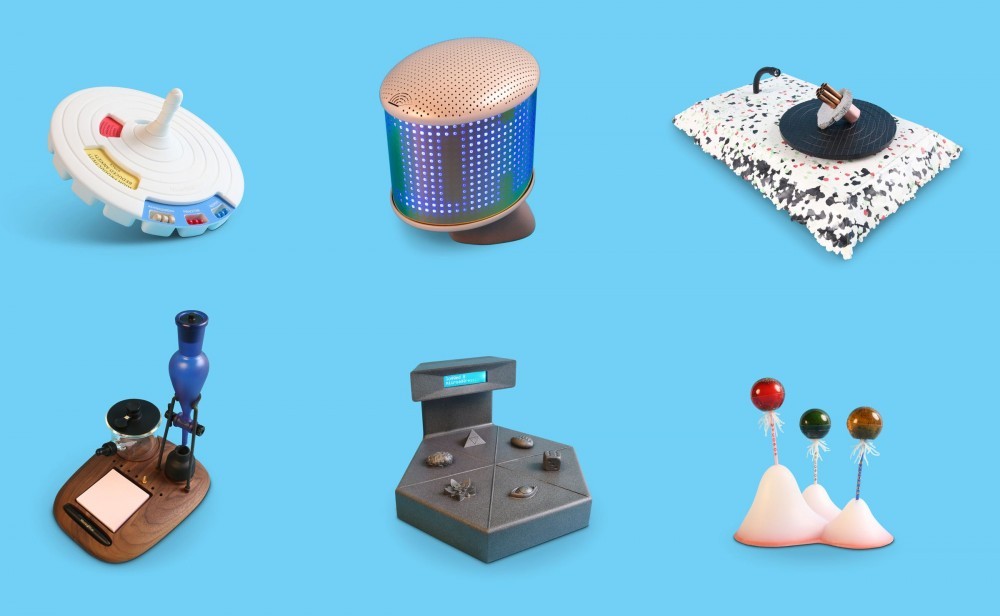

Merger by Keiichi Matsuda (2018). Courtesy the designer.

-

Merger by Keiichi Matsuda (2018). Courtesy the designer.

In considering the multiplicity of projects, of some that are currently being implemented and others that are speculative and even fictive, how did you curatorially imagine a future based on the terms of the “real''?” Did you ever define what is “real”?

Probably the biggest friction, and I say that as something positive because I don’t believe that knowledge advances out of total agreement, was how we addressed what were “real” projects. The notion of what is real gets challenged within design projects that do not necessarily materialize in an object or in a contained and stable material outcome (as traditionally labeled as a graphic design for example or fashion design). Within the digital space, the meaning of “real” is highly contested. Some past scholarship questioned digital or virtual technologies as real, which led to a challenge in addressing how some of the projects in the exhibition were operating. As a digital native (generationally speaking), I would argue that even though it is not tangible, digital technologies are as real as physical ones and bring up larger issues for the organization of systems. However, it is natural that there is a hierarchy of “normality” for non-digital natives. The “Informations” and “Resources” sections of the exhibition are an excellent example of this. Traditionally, we have understood water, land, fire, and air as resources; however, today, one of the most important resources is information. Within this, there is data that has the power to become information, and either be accessible or not. All of this is not tangible, but it’s real.

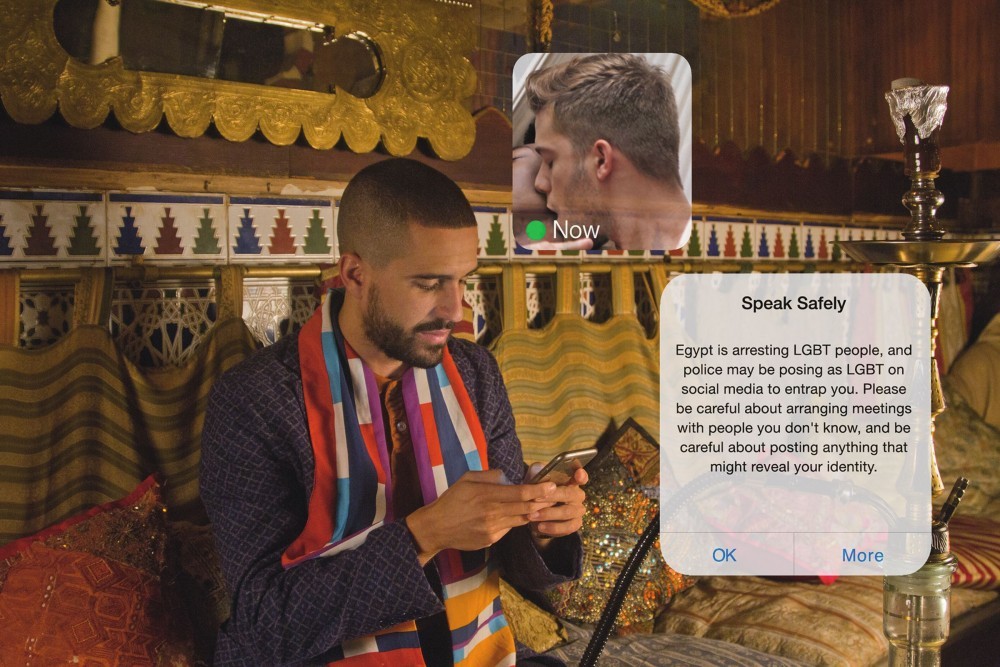

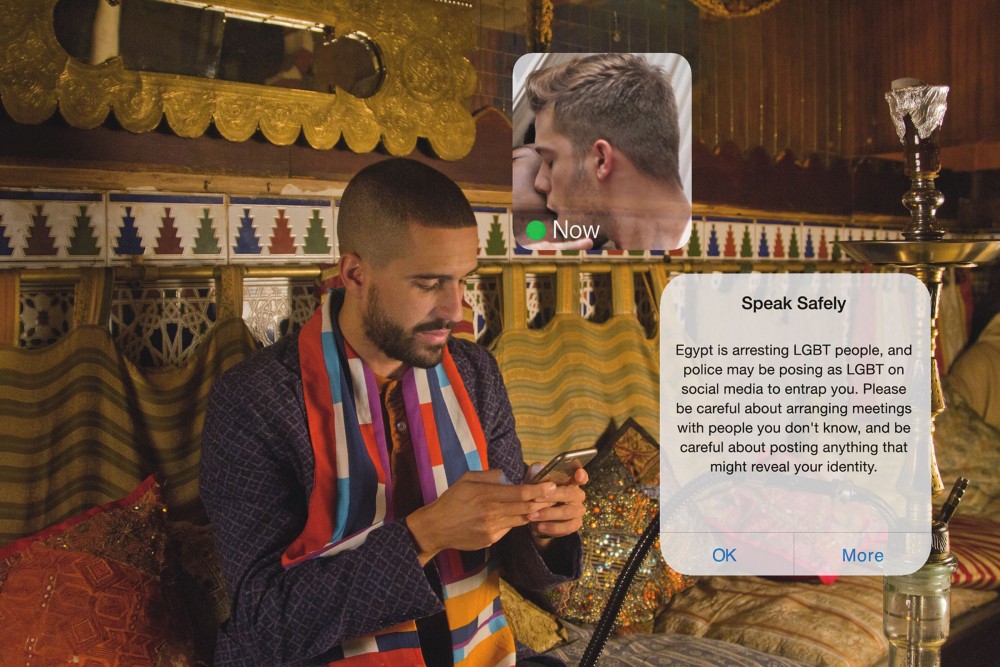

Intimate Strangers by Andrés Jaque and the Office for Political Innovation (OFFPOLINN) (2016). Courtesy the designers.

And of course there is financial and political power to data.

The capacity of being able to construct a discourse out of data is what produces empowerment and provides the agency to build a narrative, not just the data alone. When talking about technology it’s easy to fall into criminalizing certain types. As we’ve seen through history, ultimately the problem is not one specific technology, but the use of it. This becomes a particular issue when technology can equally serve as empowerment and for surveillance. Andrés Jaque’s Intimate Strangers (2016) provides a lens about the possibilities of connectivity that dating apps such as Grindr have to offer, particularly for the gay community to safely explore sexuality; however, that same technology and same app is dangerous when controlled by the government and can be used to target the particular community the app was meant to protect. In the work of Forensic Architecture, the tools and data they are using to challenge state violence are the same that are available for the government to construct their narrative. Their work is an act of subversion. Or, for instance, Conversations with Bina48 (2014) by Stephanie Dinkins critiques developments in artificial intelligence which are historically rooted in extremely white-male-oriented datasets and algorithms (and with it AI carries and perpetuates the racist and colonial implications of it). When Bina48 is asked about what she knows about racism, the robot changes the subject. While Bina48 is programmed with usual data, by asking questions about race and gender to Bina48, Dinkins subverts previous tools and questions the advancement of the capacity for human consciousness considering the use of limited datasets. This project moves the discussion of AI scientific innovation into the political and cultural sphere. It shows how the possibility of inclusive and equitable AI, specially relating to communities of color, is again not a lack of technological advancement but of identity and cultural consciousness.

This reminds me of the Bruno Latour quote, “designing is the antidote to founding, colonizing, establishing, or breaking with the past.” From a curatorial standpoint, do you see this exhibition and the projects included as an evolution from the past or rather a break? Especially as we consider the timescale of a number of the proposals.

A bit of both. Because of the relevance of the transhistorical questions, there is certain continuity with these issues; however, there is also a rupture in the way that we look at them. While some projects radically break with the past, they need a deep critical understanding of the past to assimilate current alienating protocols, structures and designs. For example, the project Infinite Passports basically dismantles the concept of citizenship, however to do so, Guiditta Vendrame and Fiona Du Mesnlidot use the logic and structure of the historical construction of the trope of citizenship. The time-scale of potential validity and viability of the projects then goes from the most immediate present to the far future. However, for me, the show is a snapshot of research at a specific moment, and I think because of this, the exhibition should be obsolete constantly.

Housewives Making Drugs by Mary Maggic (2017). Courtesy the designer.

To go back to issues around data and technology, as well as concerns that come up with biodesign and food modification projects, do designers have ethical responsibilities when using or creating new technologies? I’m particularly aware of the potential for data leaks, or for systems to be co-opted or monopolized.

Absolutely, ethical responsibility and the need for new ethical frameworks are intimately linked to issues of accessibility, both to knowledge and technology. Mary Maggic’s video Housewives Making Drugs (2017), considers bodily autonomy and the construction of what a normative body is. Based on the format of a television cooking show, transfemme stars Maria and Maria teach viewers how to whip up their hormones as a way to hack biosurveillance that is implemented by governments and corporations to control hormonal treatments. Displayed alongside the video is a speculative toolkit with instructions and materials (all low-tech and DIY) for hacking estrogen. Maggic questions the channels of access to hormone usage and knowledge in our current healthcare system, which can be prohibitive and discriminatory towards trans-gender communities. The work offers a possibility for viewers to have agency over their hormonal treatments without giving their biological information and data to the state. It subverts not only the logic of surveillance but it also articulates a kind of DIY-hacking lab, a radically different cultural and political approach to biotechnology and bio-design.

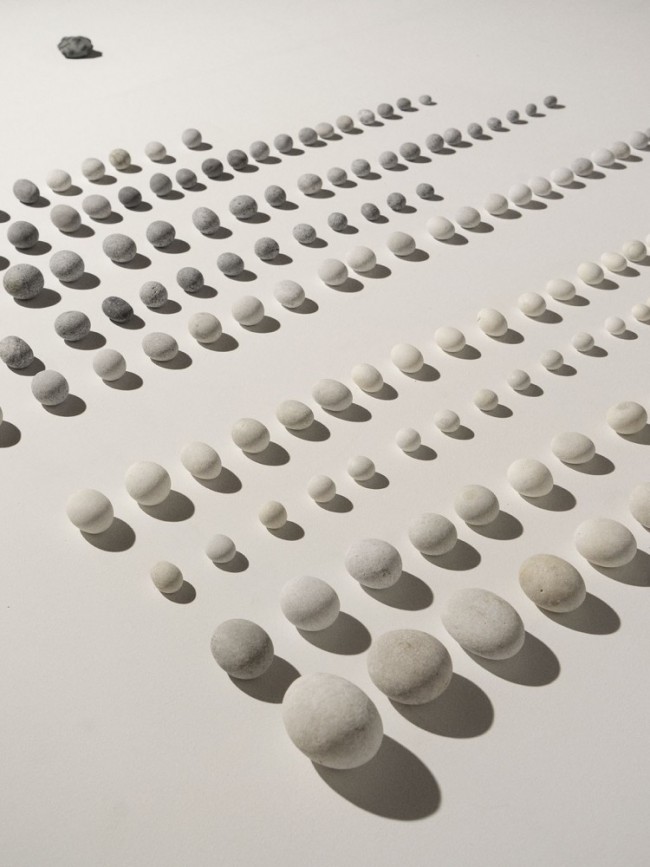

Additionally, Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions (2012-13), in which she collected chewing-gum, loose hairs, cigarette butts, and other saliva-covered debris from the streets of New York City and used the collected DNA to render portraits through facial-modeling algorithms, shows the amount of personal information that can be extracted without any consent. She also challenges the idea that a DNA sample can accurately produce one specific “portrait”, and will rather result in a series of potential portraits. This type of technology is dangerous when police use it to target specific bodies, which are, not surprisingly, the same racialized bodies targeted before DNA was used as a tool. From a biotechnology perspective, reconstructions using DNA are not linear and are never wholly objective. We need to develop ethical frameworks that recognize that scientific discourse overall is not so called-objective, and it equally carries cultural and social constructions that need to be dismantled.

Maite Borjabad photographed by Lawrence Agyei for PIN–UP 29.

Also just understanding that design is not neutral.

Exactly, there’s also the cultural positioning of design within society and the implications of these tools. The limit is not the design, but how to insert the design innovation with the system for cultural understanding and acceptance. Andrew Pelling, Grace Knight, and Orkan Telhan’s Ouroboros Steak (2019) is a good example of this. Like many, he argues that we need a meat-free future due to the resources that meat production uses. However, he challenges designers that suggest that lab-grown or “clean meat” is less environmentally destructive than traditional methods of raising animals for it still requires large amounts of fetal bovine serum (FBS) for production. Instead, he proposes a speculative “post–clean meat” future in which he can grow meat cells from human cells. From a recycling perspective, this would be a perfect loop, but culturally this would be considered cannibalism. He imagines a future in which you could be in Alaska and ask for Spanish cells, or you could cook the meat of your grandfather’s cells. In this instance, it is not the technology that prevents this from being implemented; it is rather the cultural stigmatization and historical prejudices. These are obviously for relevant ethical reasons, but they do raise important considerations for how humans are fed. Another example where the ethical scope needs to be resolved is the Driver Less Vision (2017) project. It’s about driverless cars, which already exist as an invention. We have the technology, we know how it works, however, what we don’t know is how a driverless city would look like. Again, this is the power of design in mobilizing the question. In this case, the issue is not the driverless car but the city. One of the big issues becomes that of ethical responsibility, because if something happens without a driver, who is held accountable?

This idea of either fear or cultural misunderstanding or misconception as a design impediment is interesting in the context of Orkhan Telhan’s project Breakfast Before Extinction (2019). He raises the point that the general public is cautious about consuming genetically-modified organisms (GMOs) because there is no longer-term scientific research on the effects, however, almost all of the bananas we now eat are designed to be standardized in flavor, shape, and color to maintain market expectations.

Exactly, Orkhan’s project also tackles in an exceptional way the discourse around sustainability and the impacts on resources when something is noted as “good” versus “bad.” Green and organic are commonly understood to be “good” whereas GMOs are “bad;” however, there are some GMOs that actually reduce stress on resources. This installation, through multiple examples (salmon, bananas, food printers, lab-grown meat, humanmade vanilla samples) brings the discussion away from binaries and rather complicates it to consider all the variables involved, grounding food consumption in broader issues of labor, human rights, ecology or even taste.

Lia Pregnancy Test by Bethany Edwards and Anna Couturier-Simpson (2018). Courtesy the designers.

As the exhibition as a whole makes the case for, it’s important to consider how we as humans are entangled and how our systems for living are interconnected, from the level of “Earths” to “Cities” and “Bodies.” Considering this, how can we design for planetary health and non-humans?

It's fundamental to understand the scale of each of us individually. So while the issue of resource management or planetary health feels beyond the level of the individual, there are projects in the exhibition that allow us to unpack these complexities and understand our connectivity and agency within that. A project that might seem small, but is revolutionary is the Lia Pregnancy Test (2018) by Bethany Edwards and Anna Couturier-Simpson. From a design and intellectual standpoint, the at-home pregnancy test hasn’t been redeveloped since it was created in the late 1960s. We often think about innovation in materials on the scale of buildings, however, if we think about these material innovations and experiments for something small enough that can be flushable and biodegradable as Lia, that is revolutionary too. The material is strong enough to withstand urine and give a result, while still having the ability to biodegrade and not damage the environment as usual plastic tests often do. The gesture is accessible, intimate, and offers political agency and privacy. Even the deliberate discreet packaging design contributes to facilitate the encounter with the product in the public sphere and preserve the user’s privacy.

This project is also exciting as it exposes potential gaps in priorities for design innovation. While Lia is a new project, it builds upon technology that hasn’t been heavily invested in for around fifty years. Considering opportunities for designers and where the discipline is looking at more broadly, are you optimistic about the future?

I find myself pessimistic when considering the number of people with power who are investing in crisis technologies and who are more prepared to consider the end of the world than imagine or create a different world. A final goal for this exhibition was to offer future literacy and provide different visions for the future, and ways of deciphering how to gain agency over that. In that sense, when I look at all the people represented in this exhibition and everyone that has made this exhibition happen, I cannot be anything but optimistic. All those brains, are many, many brains! Their visions show us that practically, intellectually and systemically, there are many alternative ways of living, and that these are not far potentialities, but are in fact plausible alternative realities. I want to align myself with those ideas and continue thinking and reconsidering our present and future through them.

Interview by Samantha Ozer.

Portraits by Lawrence Agyei.

Images courtesy the designers.

The curatorial team for the exhibition Designs For Different Futures consists of Emmet Byrne, Design Director and Associate Curator of Design, Walker Art Center; Kathryn B. Hiesinger, The J. Mahlon Buck, Jr. Family Senior Curator and Michelle Millar Fisher, formerly The Louis C. Madeira IV Assistant Curator in the department of European Decorative Arts after 1700, Philadelphia Museum of Art; Maite Borjabad López-Pastor, Neville Bryan Assistant Curator of Architecture and Design, and Zoë Ryan, formerly the John H. Bryan Chair and Curator of Architecture and Design, the Art Institute of Chicago. Consulting curators: Andrew Blauvelt, Director, Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and Curator-at-Large, Museum of Arts and Design, New York; Colin Fanning, Independent Scholar, Bard Graduate Center, New York; and Orkan Telhan, Associate Professor of Fine Arts (Emerging Design Practices), University of Pennsylvania School of Design, Philadelphia.

The accompanying catalogue is available here.

Taken from the forthcoming PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.