GIGER BAR: The alpine Netherworld of H.R. Giger

Since the Giger Bar opened its doors in 2004 it has become a fixture in Gruyères. Hardcore science-fiction fans and unsuspecting tourists alike regularly enjoy its menu’s culinary perks, including staples like “alien coffee” (a Schnappslaced coffee blend) or a Giger-branded absinthe produced by venerable Swiss distillery Matter-Luginbühl.

Twenty years ago, Swiss Surrealist and concept designer H.R. Giger (1940–2014) bought the Château St. Germain, part of a 13th-century castle complex perched at the summit of the quaint village of Gruyères. A year later, in 1998, the Academy Award winner quietly opened the Museum H.R. Giger, a newly renovated permanent home for the polymath’s best-known works. Outside is a backdrop of Swiss traditionalism: cobbled streets, conventional restaurants, and tourist-friendly chocolate and cheese stores; inside is a panoply of sculptures, paintings, furniture, and film memorabilia showcasing the artist’s dark, often terrifyingly necromantic vision, ridden with skulls, cyborg demonesses, robots, penises, vaginas, babies dressed as soldiers, babies shaped like penises dressed as soldiers, and Baphomet, the goat-headed occult deity.

Left: First conceived in the early 1980s, this side table and its matching candelabra consist of six figures of the holy Christ. It’s open to interpretation whether the inverted figures of Christ make reference to the cross of St. Peter or are drawn from satanic symbolism. This version from 1992, made of aluminum and glass, is part of the museum’s permanent collection. Right: Giger conceived some of the walls of the Giger Bar in homage to his painting Landschaft (1973), which depicts a dystopian landscape of dead embryos.

Born in 1940 in Chur to a family of pharmacists, Hans Rudolf Giger was initially trained in architecture and industrial design, but his fascination for the surreal and the occult guided his career. Though he is best known for designing the eponymous monster in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), as well as for the original version of Dune (1973), his distinct artwork and illustration, heavily influenced by anatomy, erotica, and the occult, has garnered him notoriety in the worlds of illustration, film, and production design (check out his video for Deborah Harry's 1981 single “Now I Know You Know,” which Giger directed). It was his collection of paintings, “The Necronomicon” (1977), which is filled with occult symbols and detailed renderings of human orifices, that originally inspired Scott’s nightmarish extra-terrestrial (for which Giger took home the Oscar for Best Visual Effects in 1980).

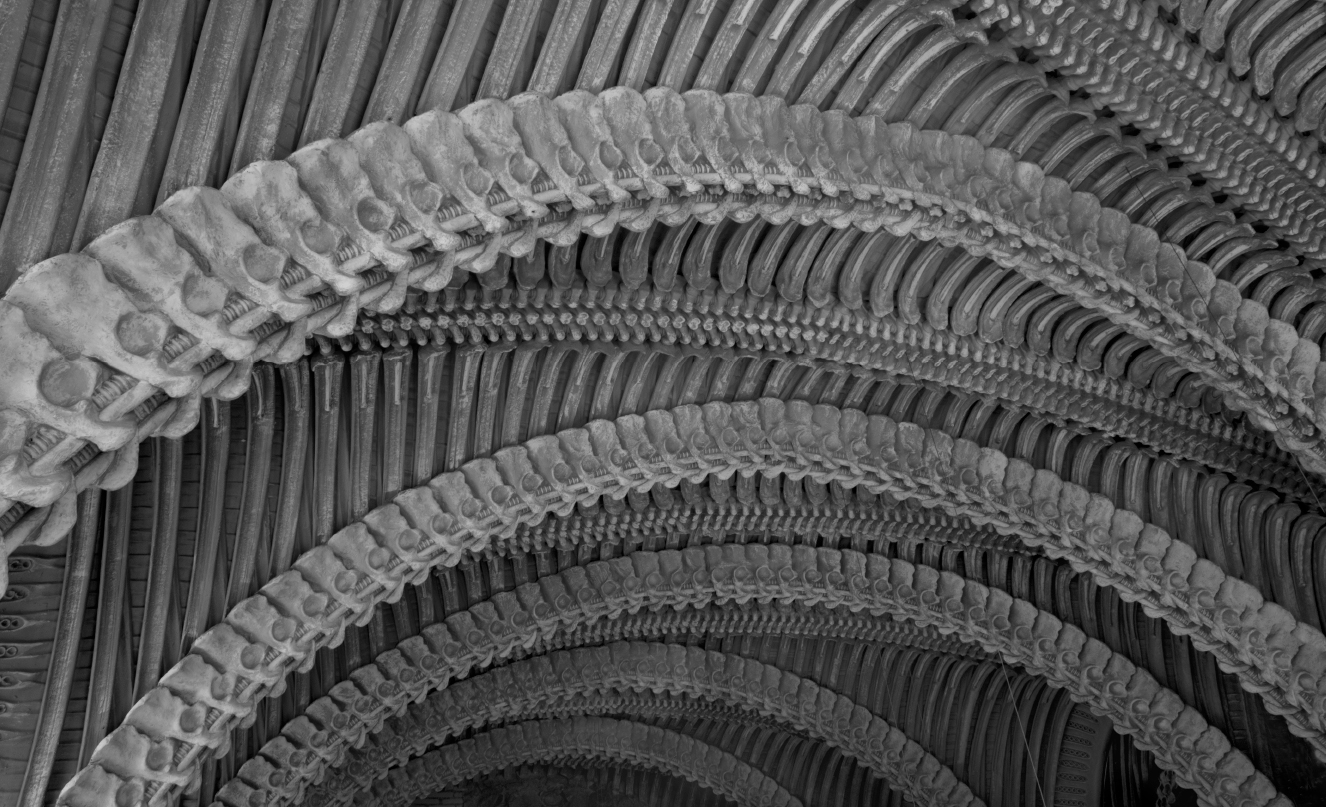

The vaulted ceiling of the Giger Bar is reminiscent of human ribs and vertebral columns. Rather than assembling the ceiling out of molded elements, Giger insisted on individually modeling the pieces in Jetcrete in his studio on the outskirts of Zürich and then having them transported to Gruyères, 115 miles south. The elaborate and costly procedure turned the construction of the 800-square-foot space into a two-year project.

While his personal artwork as well as his instantly recognizable early character models fill the museum, across the street in the Giger Bar — a cavernous space resplendent with vaulting ribs and vertebrae — the artist’s macabre, hyper-sexual, and bio-mechanical world truly comes alive. Giger spaces have previously opened in Tokyo and Chur — not to mention a bar at the legendary New York club Limelight — but it is in the Gruyères space that his inclinations in architecture and interior design are fully realized: a grid of screaming infant heads lines one of its walls; meticulously detailed tables sit on rubber-paneled flooring engraved with his signature biomechanics patterns; paintings depicting an amalgam of body parts and dubious machines hang against black felt walls, backlit by yellow light; and a massive skeletal structure covers the vaulted ceiling. It’s like stepping into a fascinating and disturbingly tenebrous netherworld — which, in Giger’s book, feels like paradise.

The Giger Bar’s hours of operation are primly diurnal, from 10:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., but inside it always feels like deepest night. Several booths invite patrons to take a break from the more conventional Swiss tourist fare on offer in the streets of picturesque Gruyères, a community of barely 2,000 inhabitants. The chairs and side table are updated fiberglass versions of Giger’s original Harkonnen designs.

A small aluminum urn (converted into a flower vase) and the table it stands on are both decked out in Giger’s signature “biomechanoid” pattern. The bull’s eyes on the urn’s lid are inspired by the glasses worn by Giger’s “birth-machine babies.”

Giger made these chairs for the set design of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film version of Frank Herbert’s 1965 science-fiction novel Dune. Jodorowsky’s movie never made it to the screen, and Dune was later realized by David Lynch without Giger’s involvement, but the artist’s designs for chairs, tables, mirrors, and other furniture pieces for Dune’s Harkonnen Castle — all made of polyester, metal, and rubber — have become Giger staples, finding their way into a number of spaces he designed around the world. The Harkonnen Capo chair also appeared in the 1981 music video for “Now I Know You Know” by Deborah Harry.

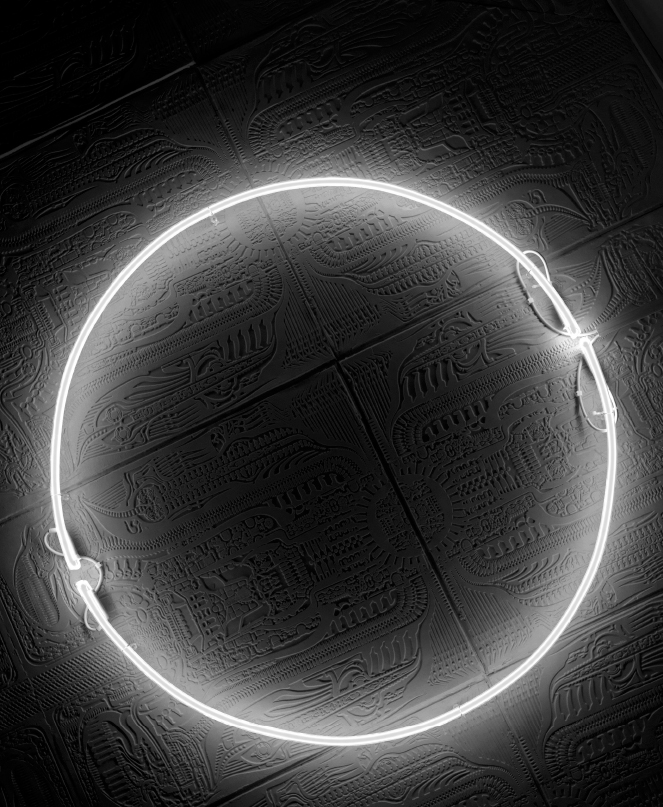

Inspired by the design of 19th-century cabinets érotiques, the space’s floors, ceilings, and walls are clad in aluminum plates engraved with Giger’s “biomech” patterns. Gnostic traditions were known to link the circular symbol to the “world serpent,” forming a circle as it eats its own tail. No word whether this is what also inspired the circular fluorescent light fixture that greets visitors as they enter one of the exhibition rooms at the H.R. Giger Museum.

A recurring theme in Giger’s work is the Earth’s overpopulation and the threat it poses to civilization. In 1977 he imagined the Todgebärmaschine III, a female cyborg that bears dead babies. Several depictions of it line the walls at the museum, including this 78 x 54 inches painting in acrylic on wood. Next to it stands an early wood and polyester model of Giger’s “biomechanoid” cyborg sculptures from 1969.

Text by Alex Moshakis.

Photography by Johnny Graf and Dominik Hodel.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 13, Fall Winter 2012/13.