DREAM CITIES: Meditations On Urbanity and Architecture in The Sci-Fi Genre

-

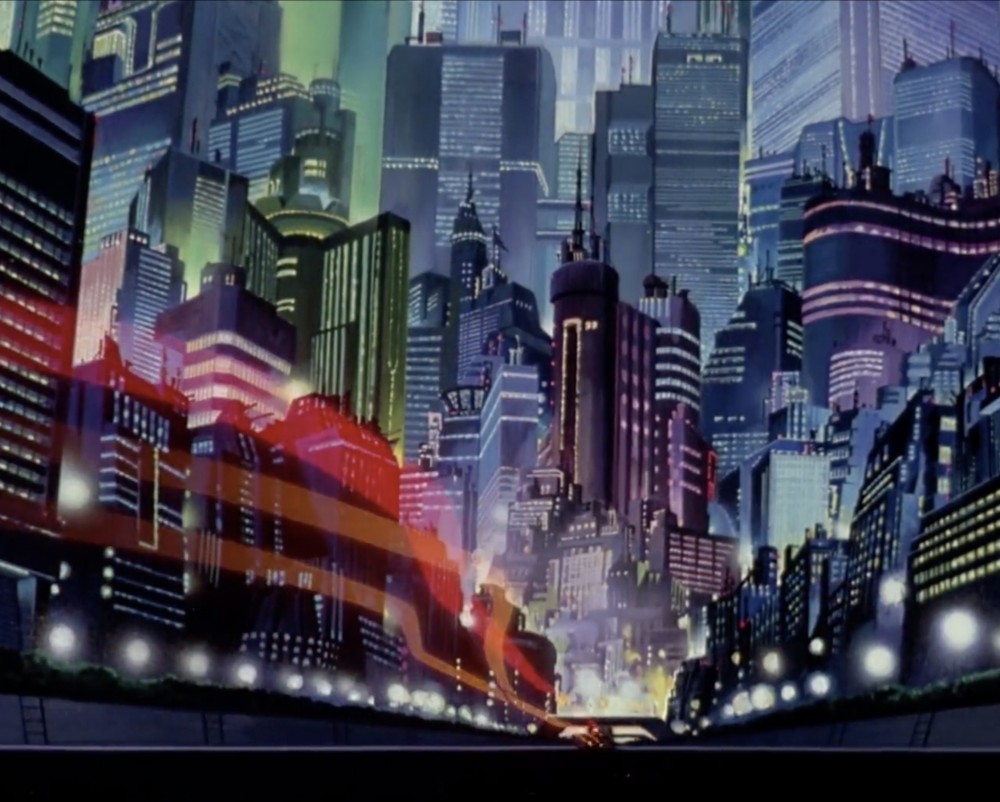

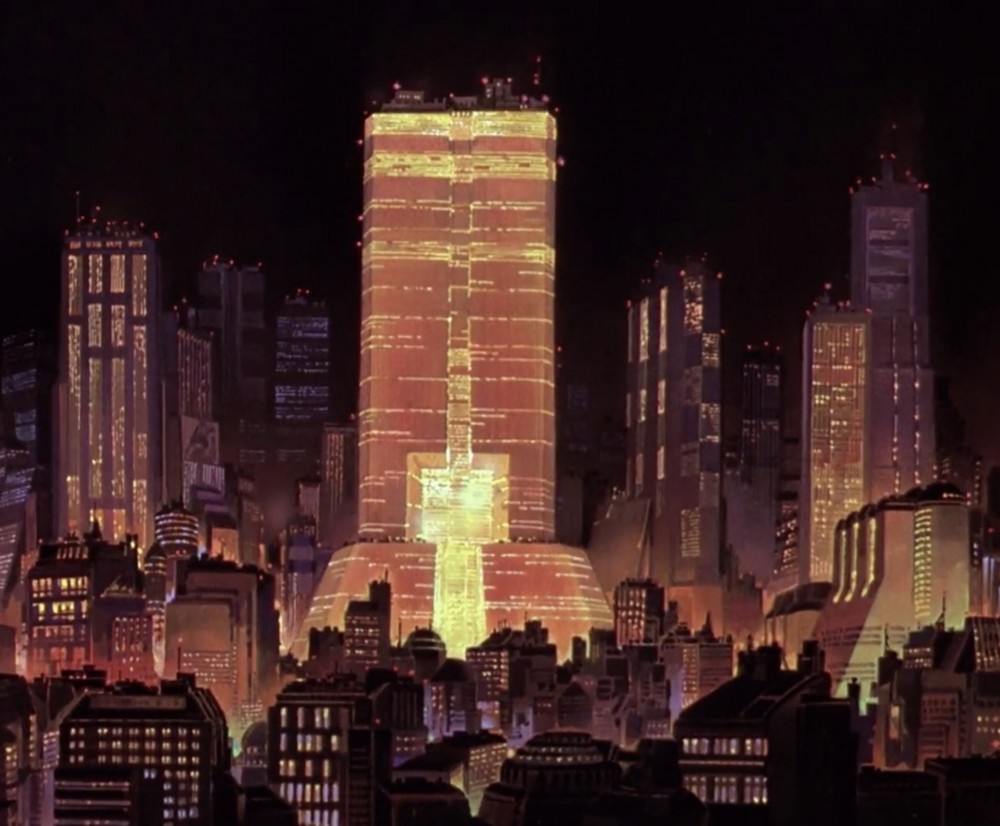

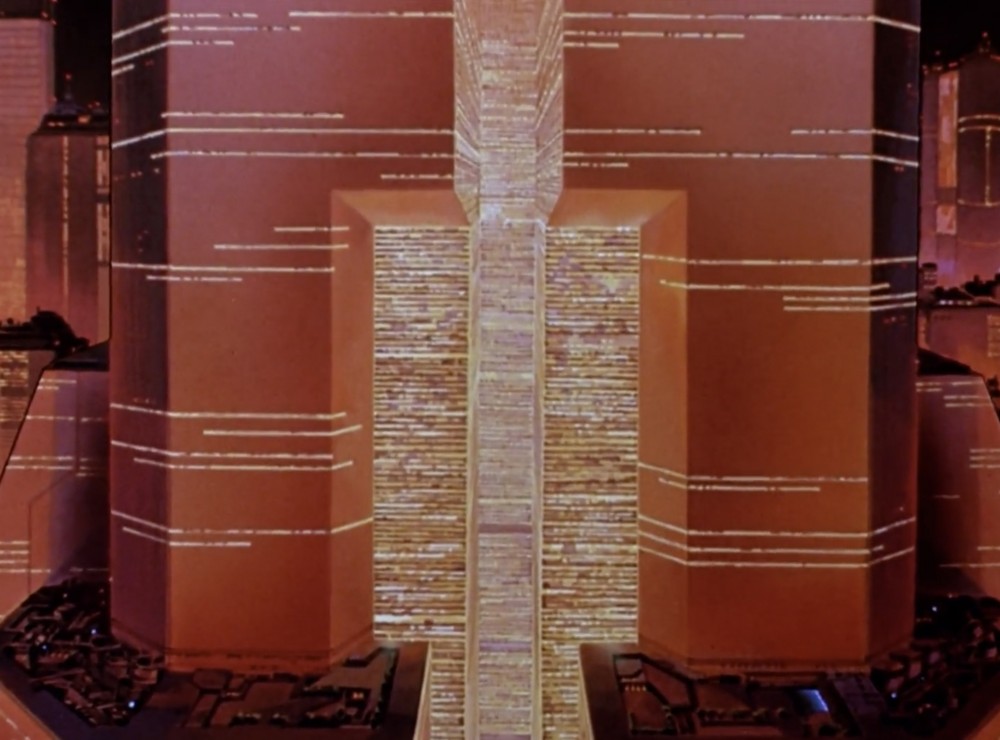

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

-

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

-

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

-

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

-

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

-

AKIRA (1988): Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo is a strange amalgamation of preceding cyberpunk and science-fiction cities: the comic strips of Moebius, the highly influential manga Tetsujin 28-gō (Mitsuteru Yokoyama, 1956), and the blinking holographic façades of Blade Runner (1982). William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer was so deeply embedded in the cyberpunk ether that one cannot help but also read his nightmare vision into Neo-Tokyo. As a city that has survived an apocalypse and is on the verge of another, it retains a certain bricolage effect — a sense that much of the city has been built atop the old. At a smaller scale, it still resembles everyday Tokyo with its paved walkways and shifting levels.

The dreamer dreams of a city that is the size of the entire world. She knows this to be true; in that way dreamers know things, because everything in the dream is already somewhere inside the dreamer. Dream and city overlap so seamlessly in her sleep that they are the same thing — the city is the dream and the dream is the city.

One night she dreams her name is Jean-Luc Godard and she is sitting alone at a mirrored café on the Boulevard des Capucines. A copy of Le Monde is open on the table in front of her. The date on the newspaper is blurred as they tend to be in dreams, but the dreamer knows it’s 1964. It’s the day Godard resolves to make a science-fiction film — a distillation of all the unreality of the world in that newspaper.

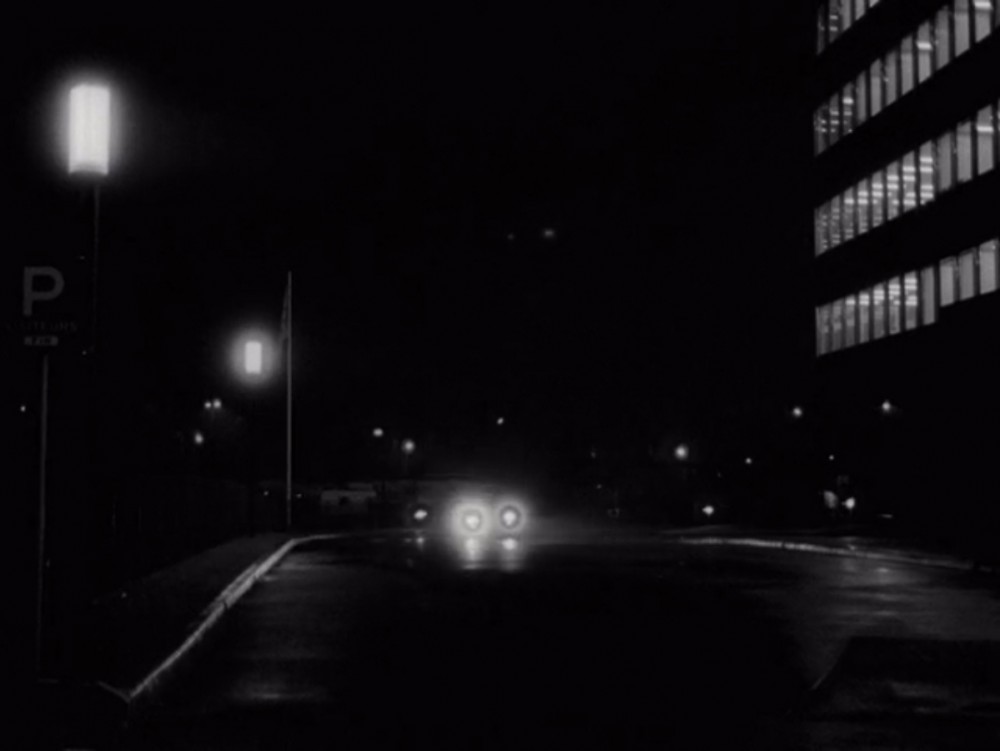

Godard names the film after the city it takes place in: Alphaville. The drama unfolds in the fluorescent corridors of sprawling bureaucratic labyrinths and the fly-by-night hotels of rapidly urbanizing Paris. There are no elaborate sets; no laser pistols or flying cars. The only recognizable sign of science fiction is the sentient computer Alpha 60 that controls every aspect of life in the city and that unmistakable, alienated Godardian dialogue for once at home in the mouths of robots — that is, if one is capable of believing that Anna Karina is a robot.

-

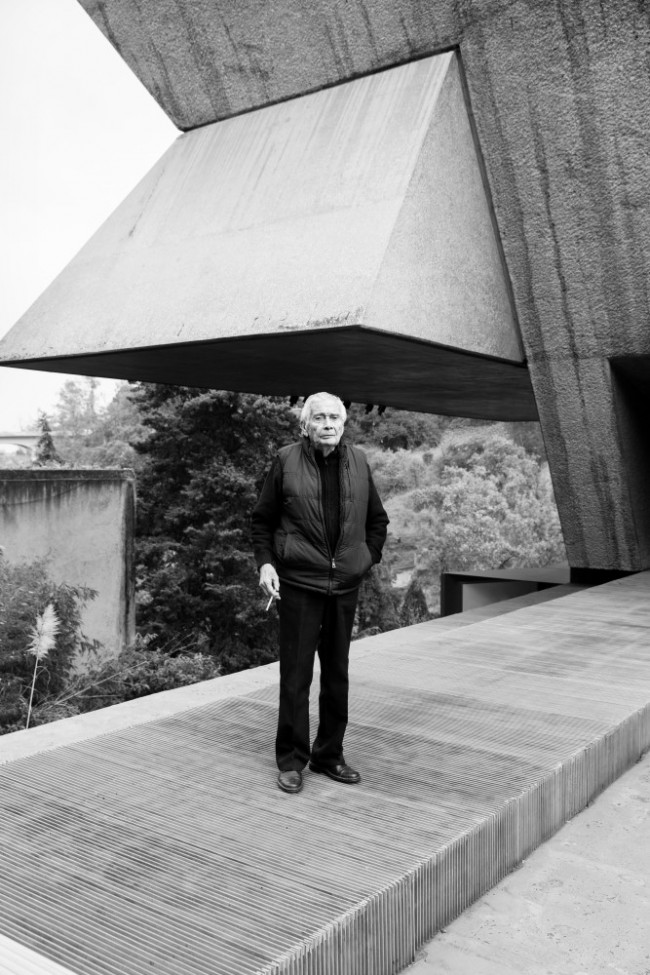

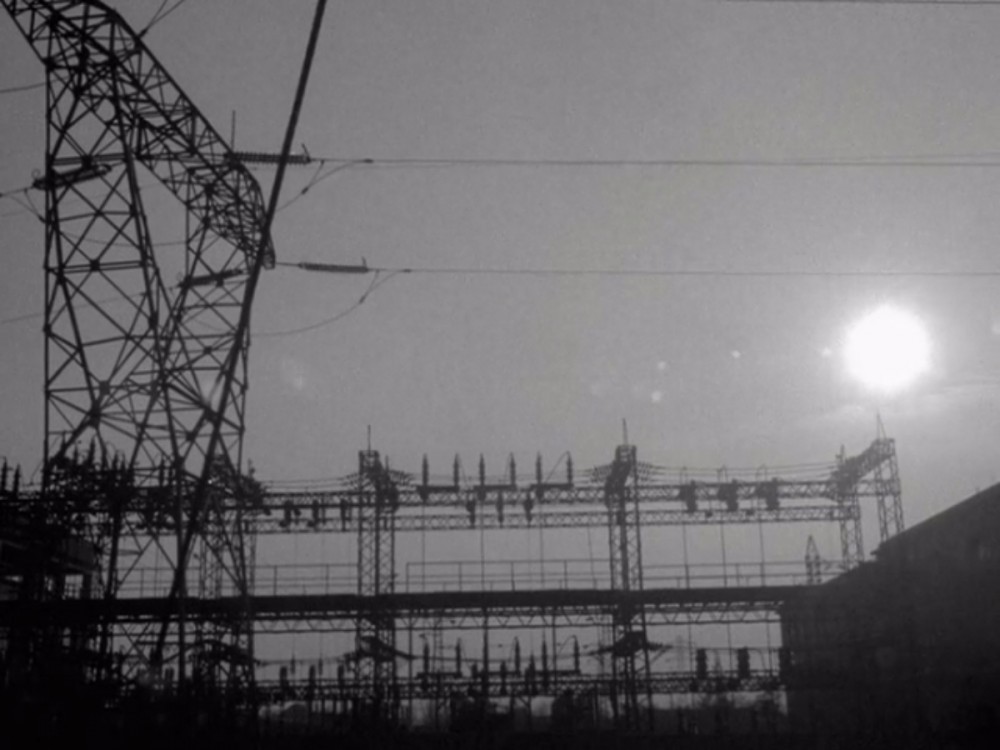

ALPHAVILLE (1965): Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal film was shot in Paris in the mid-1960s, a time of dramatic and forceful urban expansion. Godard emphasizes the uncanny qualities of a Modernist city suddenly bursting out of the Haussmannian past — a sea of neon signs and tall buildings with all the lights left on at night. Much of the film is set in the towers and coiling highways of a still-nascent La Défense and the elliptical spaces of the Maison de la Radio. These islands of Modernism were built far enough away from central Paris to placate emergent paranoia around technology, fears which the film takes to their most extreme conclusion.

-

ALPHAVILLE (1965): Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal film was shot in Paris in the mid-1960s, a time of dramatic and forceful urban expansion. Godard emphasizes the uncanny qualities of a Modernist city suddenly bursting out of the Haussmannian past — a sea of neon signs and tall buildings with all the lights left on at night. Much of the film is set in the towers and coiling highways of a still-nascent La Défense and the elliptical spaces of the Maison de la Radio. These islands of Modernism were built far enough away from central Paris to placate emergent paranoia around technology, fears which the film takes to their most extreme conclusion.

-

ALPHAVILLE (1965): Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal film was shot in Paris in the mid-1960s, a time of dramatic and forceful urban expansion. Godard emphasizes the uncanny qualities of a Modernist city suddenly bursting out of the Haussmannian past — a sea of neon signs and tall buildings with all the lights left on at night. Much of the film is set in the towers and coiling highways of a still-nascent La Défense and the elliptical spaces of the Maison de la Radio. These islands of Modernism were built far enough away from central Paris to placate emergent paranoia around technology, fears which the film takes to their most extreme conclusion.

-

ALPHAVILLE (1965): Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal film was shot in Paris in the mid-1960s, a time of dramatic and forceful urban expansion. Godard emphasizes the uncanny qualities of a Modernist city suddenly bursting out of the Haussmannian past — a sea of neon signs and tall buildings with all the lights left on at night. Much of the film is set in the towers and coiling highways of a still-nascent La Défense and the elliptical spaces of the Maison de la Radio. These islands of Modernism were built far enough away from central Paris to placate emergent paranoia around technology, fears which the film takes to their most extreme conclusion.

-

ALPHAVILLE (1965): Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal film was shot in Paris in the mid-1960s, a time of dramatic and forceful urban expansion. Godard emphasizes the uncanny qualities of a Modernist city suddenly bursting out of the Haussmannian past — a sea of neon signs and tall buildings with all the lights left on at night. Much of the film is set in the towers and coiling highways of a still-nascent La Défense and the elliptical spaces of the Maison de la Radio. These islands of Modernism were built far enough away from central Paris to placate emergent paranoia around technology, fears which the film takes to their most extreme conclusion.

Godard dreams of a city the size of the entire world and that city is a film and that film is a city. Nowhere is this continuity between film and city more evident than in the moment when Alpha 60 transforms from a disembodied voice on the PA systems of offices and hotels into the voiceover narrator of the film itself. A voice in the dream becomes the voice of the dreamer. At that very moment, Alphaville becomes a film about a fantasy city narrating itself — a figure staring into a mirror and speaking its history aloud.

To be sure, cinema emerged at the same time as the modern metropolis. The movie theater was a screen in a dark room in the center of a city onto which dreams of other cities were projected. A machine for travel no different than an airport or a train station. Sitting in that café, Godard dreams of a protagonist for us to follow, a detective named Lemmy Caution. Detectives, sailors, thieves, streetwalkers — these are the protagonists of our novels and films, the characters that take us along on their endless ambulations through the city. Their narratives follow a Dickensian grammar showcasing the poverty of the city before revealing its splendors; the unfolding of plot becomes the unfolding of place.

-

INCEPTION (2010): In Christopher Nolan’s Inception, limbo is the lowest level of dream space — a city at the edge of an infinite sea. The metaphorical associations between the unconscious and bodies of water are as old as storytelling itself. This city is a sprawling grid of generic towers, ruins, and plazas punctuated at times by personal and idiosyncratic architecture from the main character’s memories, such as an apartment which is reconstructed from his mind down to the most granular detail. Another character lives in a house on a cliff replete with imaginary personal bodyguards and traditional Japanese interiors.

-

INCEPTION (2010): In Christopher Nolan’s Inception, limbo is the lowest level of dream space — a city at the edge of an infinite sea. The metaphorical associations between the unconscious and bodies of water are as old as storytelling itself. This city is a sprawling grid of generic towers, ruins, and plazas punctuated at times by personal and idiosyncratic architecture from the main character’s memories, such as an apartment which is reconstructed from his mind down to the most granular detail. Another character lives in a house on a cliff replete with imaginary personal bodyguards and traditional Japanese interiors.

-

INCEPTION (2010): In Christopher Nolan’s Inception, limbo is the lowest level of dream space — a city at the edge of an infinite sea. The metaphorical associations between the unconscious and bodies of water are as old as storytelling itself. This city is a sprawling grid of generic towers, ruins, and plazas punctuated at times by personal and idiosyncratic architecture from the main character’s memories, such as an apartment which is reconstructed from his mind down to the most granular detail. Another character lives in a house on a cliff replete with imaginary personal bodyguards and traditional Japanese interiors.

In Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Freder, the daydreaming son of a wealthy industrialist, is interrupted in his garden by the young and beautiful Maria. She is with a group of poor children on a mission to see how the wealthy in their city live. After her disappearance, Freder descends into the lower depths of the Art Deco metropolis and ends up siding with the workers against his own father. The tropes of son against father, prince in pursuit of lowly maid, and the clash between workers and power are all just devices for showcasing the city — its fire breathing machines, its smooth metallic surfaces that leapt fully-formed from the pages of Antonio Sant’Elia’s 1914 drawings for La Città Nuova.

-

BLACK PANTHER (2018): Wakanda’s Golden City needed to perform futurity at the level of an establishing shot and also at a more intimate scale, given director Ryan Coogler’s tendency toward tight framing. As a solution, production designer Hannah Beachler was attracted to the sinuous lines and continuous surfaces of Zaha Hadid’s architecture and the way they retain their space-age qualities even in the smallest of spaces. Golden City, which features traditional typologies like an open-air marketplace and a rail line, also bears striking similarities to the postcolonial architecture of places such as Abidjan and Dakar with their assimilation of space-age shapes in the fervor of post-independence.

-

-

BLACK PANTHER (2018): Wakanda’s Golden City needed to perform futurity at the level of an establishing shot and also at a more intimate scale, given director Ryan Coogler’s tendency toward tight framing. As a solution, production designer Hannah Beachler was attracted to the sinuous lines and continuous surfaces of Zaha Hadid’s architecture and the way they retain their space-age qualities even in the smallest of spaces. Golden City, which features traditional typologies like an open-air marketplace and a rail line, also bears striking similarities to the postcolonial architecture of places such as Abidjan and Dakar with their assimilation of space-age shapes in the fervor of post-independence.

-

Black Panther (2016) Ryan Coogler.

-

BLACK PANTHER (2018): Wakanda’s Golden City needed to perform futurity at the level of an establishing shot and also at a more intimate scale, given director Ryan Coogler’s tendency toward tight framing. As a solution, production designer Hannah Beachler was attracted to the sinuous lines and continuous surfaces of Zaha Hadid’s architecture and the way they retain their space-age qualities even in the smallest of spaces. Golden City, which features traditional typologies like an open-air marketplace and a rail line, also bears striking similarities to the postcolonial architecture of places such as Abidjan and Dakar with their assimilation of space-age shapes in the fervor of post-independence.

Another night, our dreamer dreams in anime. She is flying over a city called Neo-Tokyo. She knows that the old city was destroyed by an extinction-level event. She can see the warring motorcycle gangs, the clashes between protestors and police, and the espers prodded by scientists in the military towers at its center. In Akira the dream city is set to fever pitch. Floating overhead, the dreamer witnesses the rebels at war with an empire as in the first Star Wars Trilogy and the multi-leveled city of Blade Runner with its blinking holographic façades and interminable rainy night. She sees the blend of techno-futurism and Gaia-driven mysticism from Dune and The Fifth Element. At certain moments, Neo-Tokyo threatens to become the film itself. As if set in the overlapping planes of an early Cubist painting, point of view remains fugitive and the dreamer is lost in the collision of light and surfaces that form the kaleidoscopic immensity of the city.

In Akira’s final scene, the dreamer watches as Neo-Tokyo is consumed whole by another nuclear event. The film has to end because it is the dream of a city that is no more. It is reduced to that smoldering vision of the real world that Morpheus shows Neo when they stand in the white space of a computer program. And suddenly the dreamer is in there with them too, in The Matrix, a place where humans and machines are at war. Asleep in liquid electrical pods and harnessed for their energy, humans spend their waking lives in a computer simulation created by the machines. A group freed from the pods lives in the subterranean city of Zion and wages war against the machines by leaping back and forth between the real world and the simulation. For these characters, to travel between the two cities is to become infrastructure; to slip into telephone lines and fiber-optic cables; to crawl through vents and sewers. At times they are waveforms sent up like smoke signals between towers. Neo is an actor gone totally rogue. In the simulation, he can fly and stop bullets, and even alter the geometry of the city. He can control the film camera, forcing it into slow motion and elaborate circular pan shots. The real world and its warren of tunnels and electrical cables is the interior of a film camera. To exit from the matrix into reality is to enter the medium of cinema itself.

-

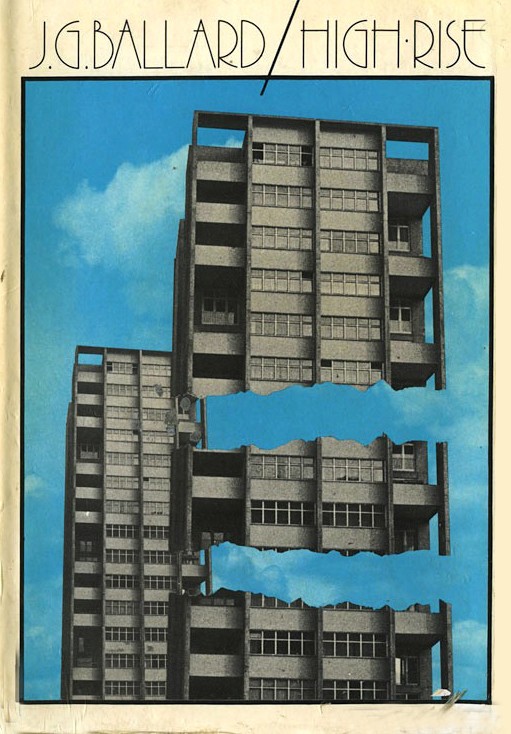

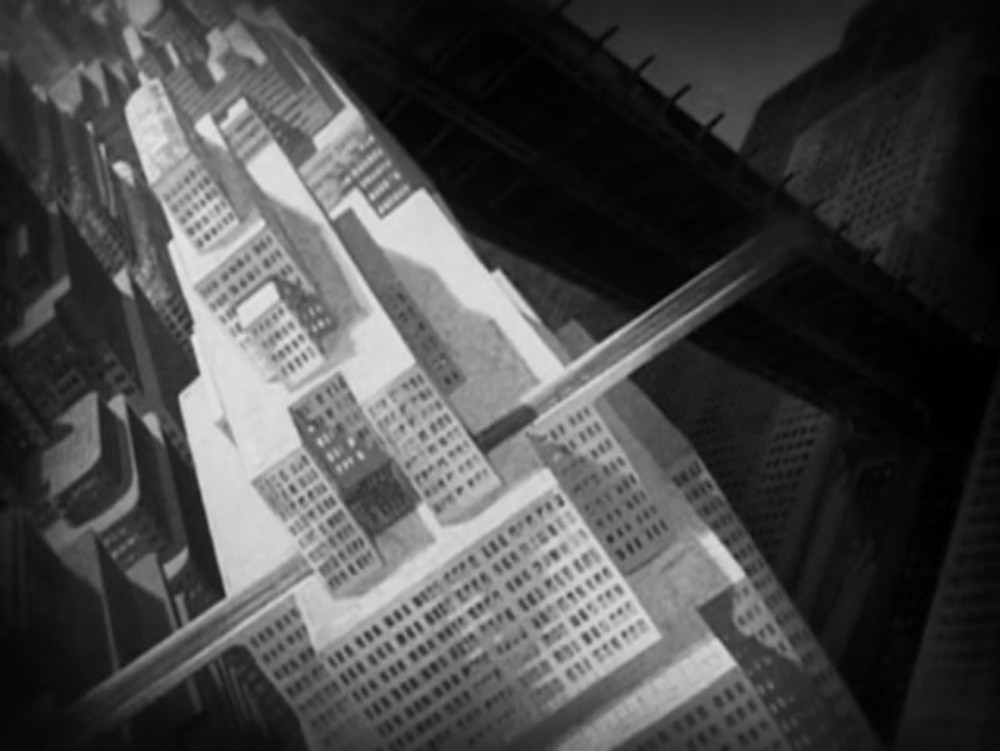

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

-

METROPOLIS (1927): Metropolis emerged from director Fritz Lang’s fantasy vision of a New York suspended in the skies, an almost abstract vision of modernity. It’s an eclectic vision too, at once a dystopian hyper-industrialized future as well as a stylized Art Deco city of automobile finishes. Lang’s influences include the writings of the futurist F.T. Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio, and the drawings of Antonia Sant’Elia. He also draws heavily on 19th-century literature like Gustave Flaubert’s terrifying vision of ancient Carthage in Salammbô (1862). Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel inspired the film’s now iconic tower.

Trapped with Neo in a subway station somewhere between two worlds, the dreamer experiences déjà vu. She has seen places like this before in dreams of other cities, but isn’t that what makes her dreams feel like dreams, that she’s already seen everything in them before? A brief dissolve, and then she’s outside staring up at a flash of neon from a bullet train. She’s in Golden City, the capital of Wakanda — the city of spiraling towers and curvilinear surfaces that emerge from small marketplaces and red-clay earth as if in an instant from a tribal village. Black Panther contains a city so meticulously detailed in its sets and aerial views, its costumes and imaginary machines, so complete in itself, that, once again, plot was merely an excuse to render it.

Now the dreamer is outside on a beach, the lowest level in the dream cosmology of Inception. Staring up into a painting of the heavens on the underside of a cupola, she sees the characters that fall asleep in one city, then dream of another, then again fall asleep and dream of another, all the way down to the beach where she stands. If Alphaville inserted a detective movie into a science-fiction imaginary, Inception does the same with the heist movie. The movie follows a team of thieves who enter their targets’ dreams to steal or plant information. The targets’ subconscious construct cities as defensive labyrinths designed to hide their secrets. The architect, the aptly named Ariadne, designs cities within cities that lure the target dreamer into a false sense of security. The rest of the team, like a troupe of actors, convinces the hapless targets that their dream is reality and to reveal the safe or lockbox lodged somewhere in its center. Sometimes the target has to be put to sleep in the real world, then to sleep again in the dream. To die in the dream is to fall into pure unconstructed dream space, landing on the beach of the subconscious, the very beach that our dreamer stands upon.

-

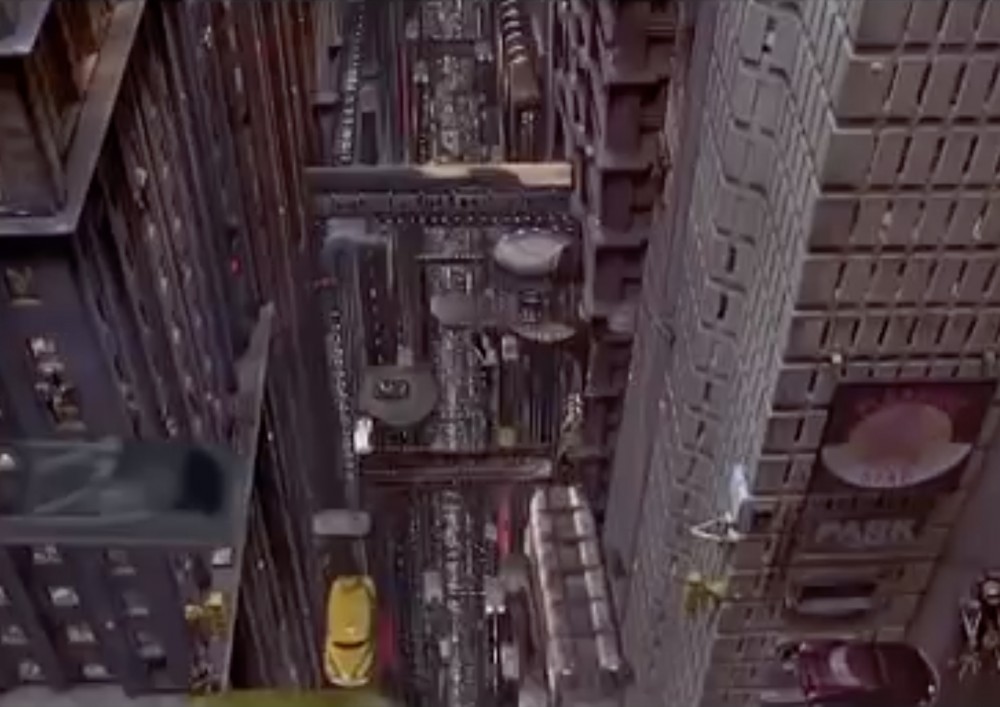

THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997): Antonio Sant’Elia’s drawings of La Città Nuova by way of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the hanging cities of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner are crucial references for Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element. The director also draws on Egyptology and astral desert mythology from the planet Hoth in Star Wars and Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, even enlisting author and cartoonist Jean “Moebius” Giraud who had worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-realized film adaptation of Dune. Besson also worked with legendary comic illustrator Jean-Claude Mézières, co-creator of Valérian and Laureline, whose planet Rubanis remains the single most significant influence on The Fifth Element’s chaotic city. (In 2017 Besson turned to Mézières again for his second sci-fi film, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.)

-

THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997): Antonio Sant’Elia’s drawings of La Città Nuova by way of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the hanging cities of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner are crucial references for Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element. The director also draws on Egyptology and astral desert mythology from the planet Hoth in Star Wars and Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, even enlisting author and cartoonist Jean “Moebius” Giraud who had worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-realized film adaptation of Dune. Besson also worked with legendary comic illustrator Jean-Claude Mézières, co-creator of Valérian and Laureline, whose planet Rubanis remains the single most significant influence on The Fifth Element’s chaotic city. (In 2017 Besson turned to Mézières again for his second sci-fi film, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.)

-

THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997): Antonio Sant’Elia’s drawings of La Città Nuova by way of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the hanging cities of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner are crucial references for Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element. The director also draws on Egyptology and astral desert mythology from the planet Hoth in Star Wars and Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, even enlisting author and cartoonist Jean “Moebius” Giraud who had worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-realized film adaptation of Dune. Besson also worked with legendary comic illustrator Jean-Claude Mézières, co-creator of Valérian and Laureline, whose planet Rubanis remains the single most significant influence on The Fifth Element’s chaotic city. (In 2017 Besson turned to Mézières again for his second sci-fi film, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.)

-

-

THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997): Antonio Sant’Elia’s drawings of La Città Nuova by way of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the hanging cities of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner are crucial references for Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element. The director also draws on Egyptology and astral desert mythology from the planet Hoth in Star Wars and Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, even enlisting author and cartoonist Jean “Moebius” Giraud who had worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-realized film adaptation of Dune. Besson also worked with legendary comic illustrator Jean-Claude Mézières, co-creator of Valérian and Laureline, whose planet Rubanis remains the single most significant influence on The Fifth Element’s chaotic city. (In 2017 Besson turned to Mézières again for his second sci-fi film, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.)

There, at the water’s edge, she steps in and drifts off into another film at a level even further below the beach. She slips beneath the current into Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death. In this city of formless and abstract architecture, of regulated collisions, palaces set like jewels in syncopated spaces, and towers that pulse then turn to sand, the dreamer is caught between the image of a smoldering planet and President Obama singing “Amazing Grace.” She lives in the cut, in the break as the bard would say. She is the sunglasses that fall from one stunned onlooker’s face; she’s the child that leaps from a top step into a YouTube clip. These are not representations of life in the city, but rather the city itself. The form of the city — the endless transformations of a black city in the rhythmic cutting and reassembly of images. An architecture born from the structure of black music, from the collision of seemingly disparate things that predate montage, predate film, that even predate cities. Born when a system of paths cut through the forest became a form of writing and that form of writing became an urban plan and that plan a film, seen, half-glimpsed if at all, in dreams…

The dreamer dreams of a city that is the size of the entire world. She knows this to be true, in that way that dreamers know things, because everything in the dream is already somewhere inside the dreamer. Dream and city overlap so seamlessly in her sleep that they are the same thing — the city is the dream and the dream is the city.

Text by Mahfuz Sultan.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.