TANNING: The Fluctuating Fashions of Indoor and Outdoor Bronzing

The world is on fire and I’m going to the tanning salon.

I walked past Future Tan Midtown on my first visit. The salon is positioned on the second floor of a commercial building far from the startup retail stores in Nolita. It’s easy to miss and, with its faded signs in bold font, it reads more like a relic of the past than a journey to the future. Inside, the salon smells of sour tanning lotion and burnt skin. Faux Grecian columns, off-white stucco, and chipping paint mirror the business’s outdated posters featuring buff, bronzed men and Dirrty-era Christina Aguilera lookalikes. The company claims to be “NYC’s premier tanning salon,” but the space, like the surrounding neighborhood, seems part of a crumbling empire.

Woman reclines in open tanning bed.

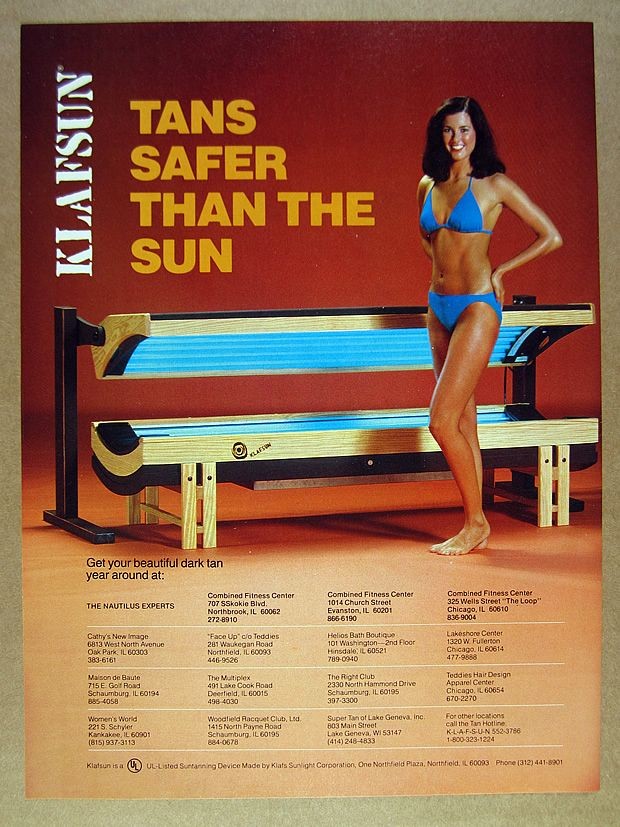

Like most relics of the 1980s, tanning salons no longer represent the futuristic excess they once promised. Today, bad perms and shiny pleather coats look cheap, as do pod-shaped tanning beds and the orange glow they leave on overcooked skin. But I’m not one to shy away from tacky aesthetics, so I sign the contract that warns me about the cancer-causing properties of UV rays, grab a pair of strapless goggles, and make my way to the back of the salon.

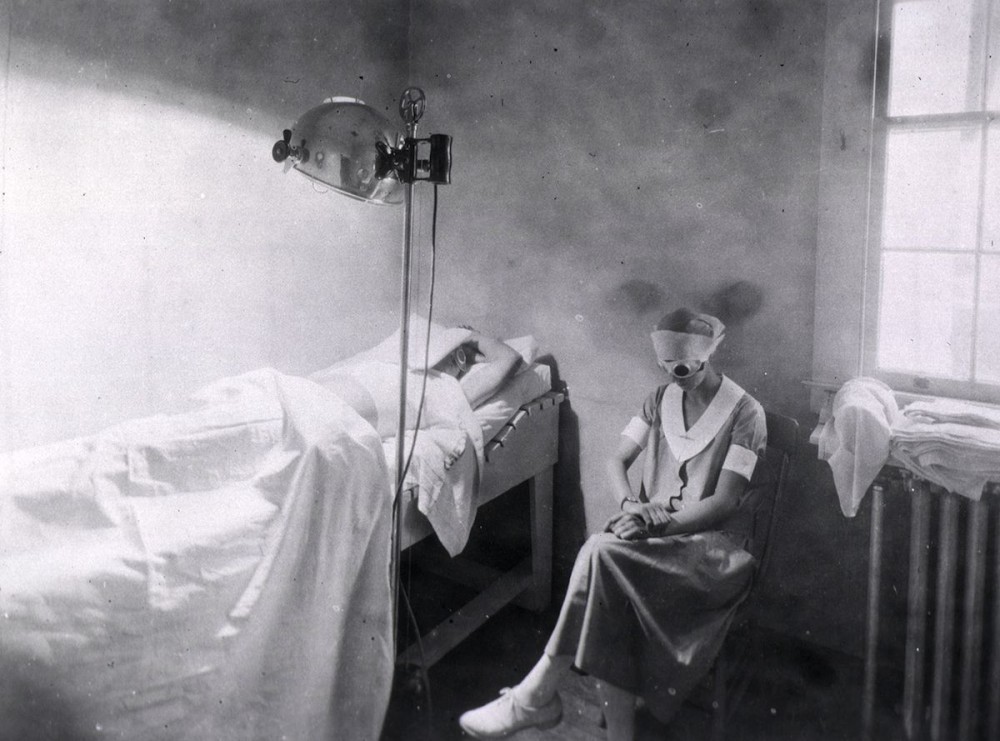

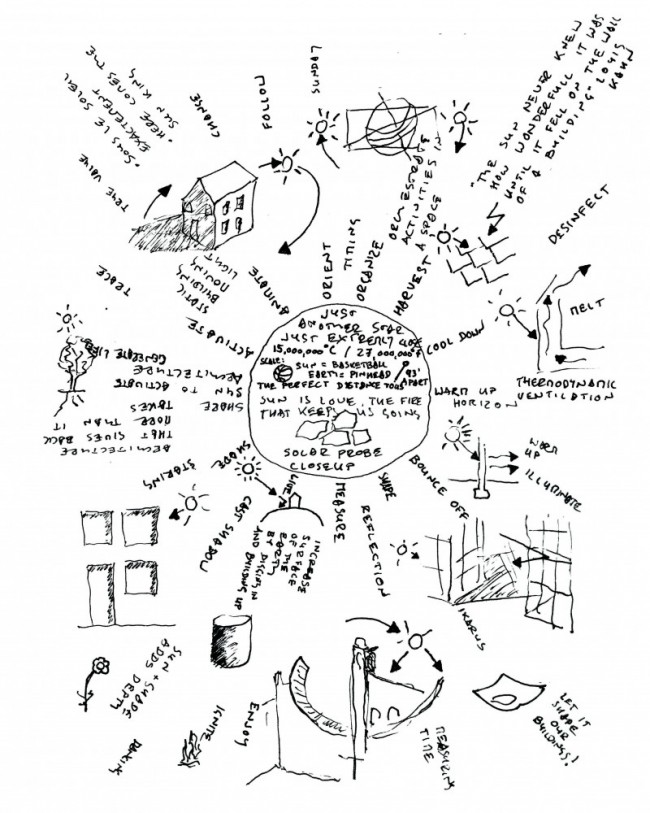

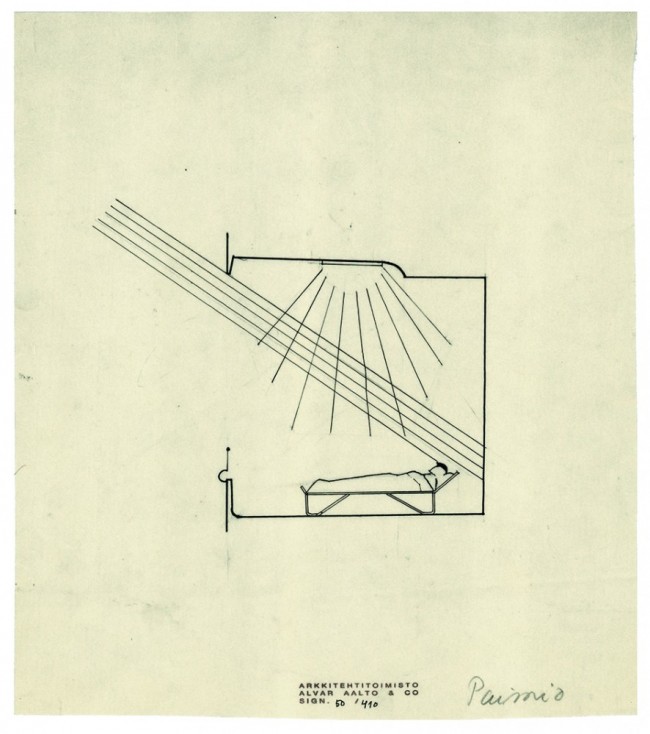

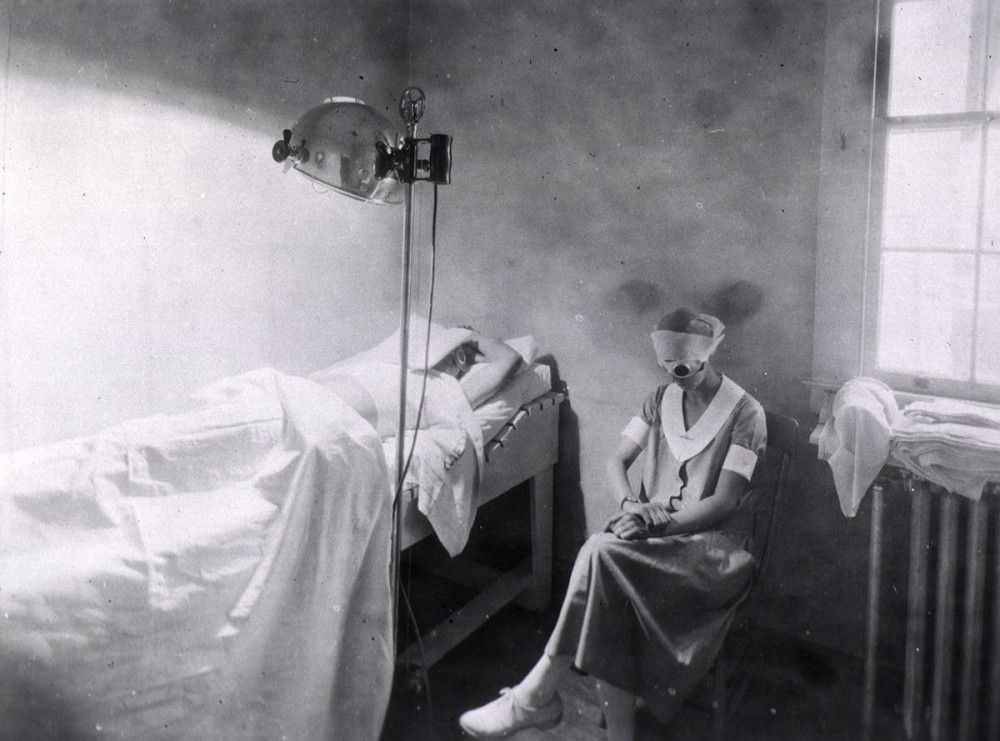

The first artificial UV rays were created by physician Niels Ryberg Finsen in the 1890s to treat cutaneous tuberculosis. By the 1920s people were installing UV “health lamps” in living rooms, children’s playrooms, and offices under the guise that sunbathing could prevent disease, improve moods, and even boost productivity in the workplace. The sun’s rays — and the UV lights that mimicked them — felt good, and while the sun’s role as a healer fell off with the rise of antibiotics in the 1950s, the idea that a bronzed glow looks healthy stuck.

Alpine light treatment in the Physiotherapy Department, U.S. Army, Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colorado, ca. 1930.

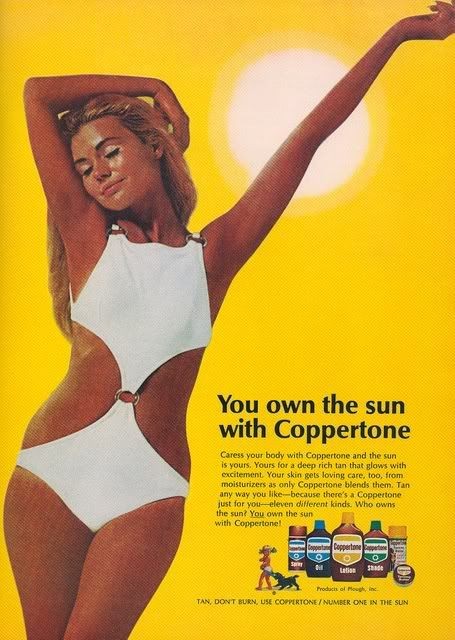

Outdoor tanning in the U.S. was popularized with the bikini in the 50s and 60s, but it wasn’t until 1978 that the first indoor tanning salon in America opened in the back of an old house in Searcy, Arkansas. Tantrific Sun was a ramshackle collection of fluorescent UV bulbs fashioned into standup 3-foot square booths fit with reflective surfaces to maximize their artificial rays. Franchises quickly spread across the country, each incorporating tropical-inspired thatched-roof huts, rattan furniture, and synthetic palm trees to match. The décor, a nod to the newly popular beach vacation, promised a transformational experience. Not just of the body, but of the mind. In a new kind of colonization of the Southern Hemisphere and the almighty star that heats it.

Ergoline Open Sun 1050 tanning bed. © Ergoline

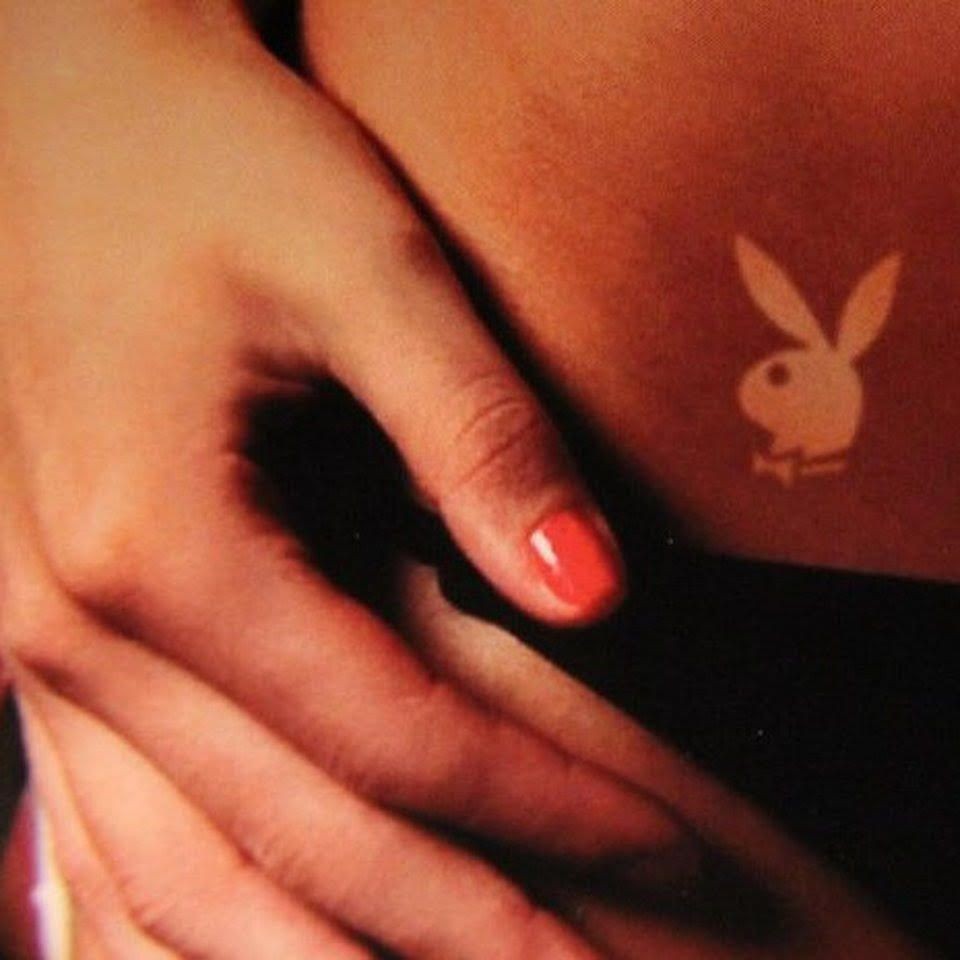

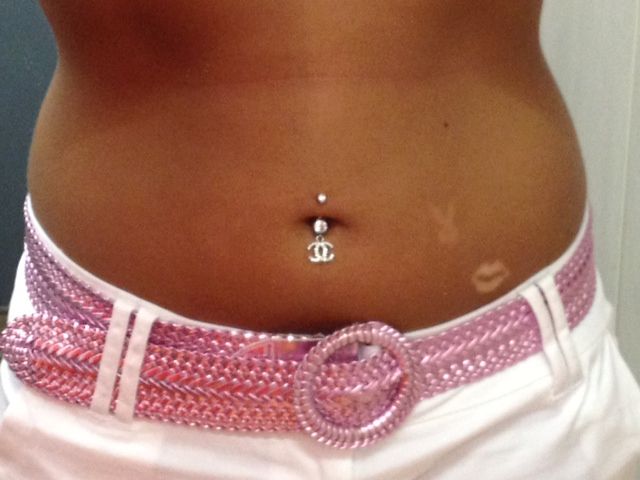

Humans have always looked for ways to circumvent nature and, with the advent of indoor tanning, it appeared that its most powerful force could be replicated without consequence. But, by the 1980s, it was becoming clear that increased exposure to UV rays, fake or real, could be damaging to the human body. There was a hole in the ozone layer, and the U.S. National Research Council had just declared that the Earth was beginning to warm. Yet indoor tanning was more popular than ever before. In gyms across America, tanning became a fashionable post-workout activity, particularly among bikini models and bodybuilders who believed that deepening their skin tone to an offensive shade made their muscles more defined. It was the era of big hair, big money, and big optimism. When the economy was good, it was easy to forget about the environment. The bronze age peaked in the early aughts, when “tanorexia” became a common ailment amongst tangerine-toned celebrities like Tara Reid and Lindsay Lohan. Famous people, like Hugh Hefner, even had their own beds, or what he called “blonde cloning machines,” at home. Monogram was big, vajazzling was a thing, and white celebrities had yet to be called out for appropriating darker skin tones.

Body art created via tanning stickers popular in the early 2000s.

This all changed after the financial crash, when the media could no longer pretend to be enamored by the expense and narcissism implied by a faux glow. In 2008, indoor tanning made national headlines when it was revealed that Sarah Palin, who had just recently changed her mind about global warming, had her own tanning bed installed in the Alaska Governor’s Mansion. This was ironic, not solely for the fact that she was following in the footsteps of hornier mansion dwellers south of her jurisdiction, but also because the man she was running with in the presidential campaign, John McCain, had suffered through skin cancer twice already. By the time the Jersey Shore characters popularized Gym, Tanning, Laundry (GTL) in 2009, indoor tanning was reserved for boardwalk rats and boisterous billionaires who didn’t mind being ridiculed for their Oompa Loompa-inspired glow. Excess in the age of financial collapse was gauche, and using real electricity to mimic the harmful rays of the sun while the Earth warmed seemed foolish.

Body Tan Salon and Spa in Riverside, California.

Today it’s hard to find a tanning salon that has UV booths. Instead we have places like Brazil Bronze and Gotham Glow that deliver spray tans so dark and true that influencers can achieve semi-permanent blackface in a matter of minutes. So, instead of encasing ourselves in the vitamin-D enriched booths of the past, we float in sensory deprivation tanks and freeze in cryogenic pods. There are light beds to alter your mood and metabolism, only they use LEDs and don’t require entombment. All of these things promise a new kind of healthy glow — but, like the tanning pods before them, they are little more than space-age cosplay, a moment spent in a Martian-like pod pretending that we might escape the future we’ve created for ourselves on Earth.

Back at Future Tan Midtown, I undress and slither into a vintage-looking Ergoline machine. The room barely fits the behemoth booth I’m about to submit to, and I begin to feel anxious thinking about the long contract full of spooky clauses I signed moments earlier. But, as the lights flicker on, a manly robotic voice begins to soothe me. I follow his instructions and start smashing buttons in search of the “aqua mist” feature. Something liquid dribbles out of somewhere, but it doesn’t feel like mist, and behind the cheap black goggles I’m having trouble seeing anything. “Relax,” I think as I close my eyes. “For the next 8 minutes, you are warm.”

Taylore Scarabelli is a writer and creative strategist based in New York City. She’s contributed to Artforum, Vestoj, and Vulture, amongst others.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.