BOX CUT: THE GEOMETRIC GARDENS OF MARQUEYSSAC

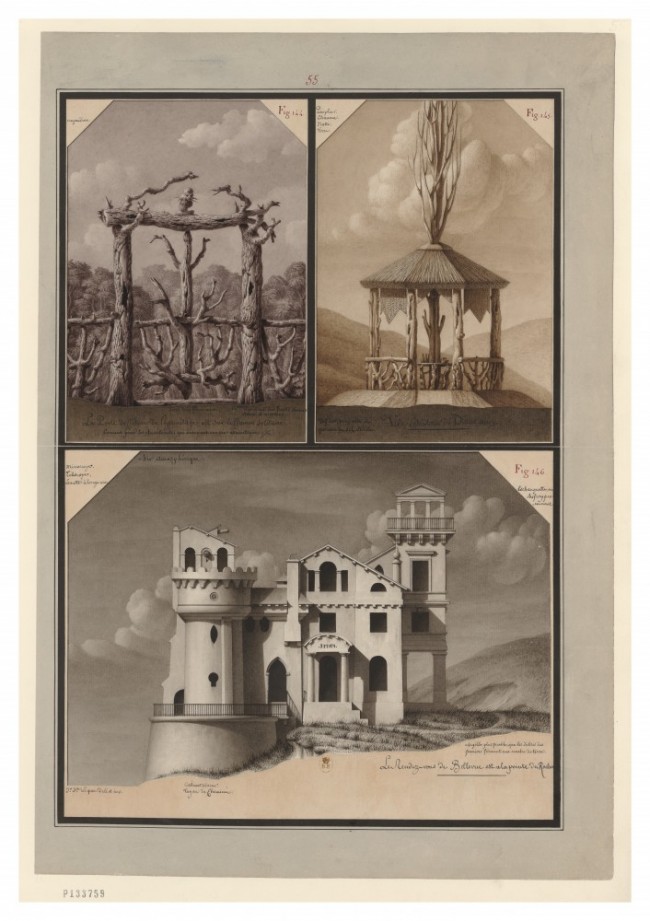

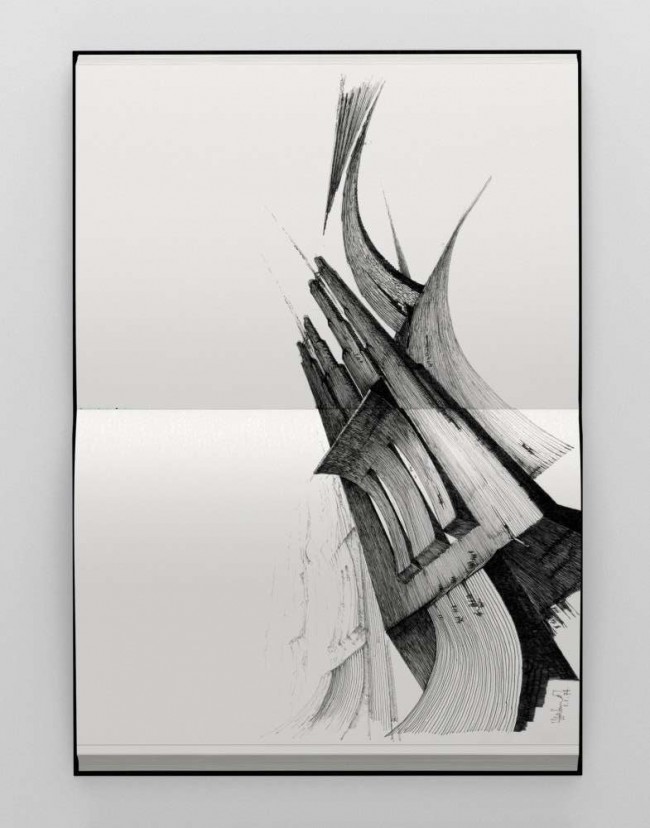

Buxus sempervirens, more commonly known as European box, has long been cultivated in gardens because of its propensity to be clipped into just about any shape the imagination might dream up. Pliny the Younger (61–c. 112 A.D.), for example, described the area around his villa in Tuscany as being “grounded with a box hedge” and “adorned with the representation of divers animals in box.” In countless classic gardens Buxus is indispensable. Where would the geometries of the jardin à la française be without the humble box? And how could the spatial and olfactory subtleties of Italian Mannerist giardini be expressed in its absence? But surely no one in the history of horticulture has ever used it as obsessively as Julien de Lavergne de Cerval in his gardens at Marqueyssac, near Sarlat, France. Suspended 130 meters over the Dordogne River in the heart of the Périgord Noir, the site was first developed in the late-17th century by Bertrand Vernet de Marqueyssac, who acquired the estate in 1692. It was he who built the massive terrace walls that allow for 22 hectares of cultivable land on this rocky spur. A century and a half later, in 1861, Cerval, his descendant, inherited the property. Inspired by gardens he saw in Italy while stationed there as a captain in the Papal Zouaves, he spent the next 30 years, until his death in 1893, completely transforming the grounds. The result is truly astonishing: a giant living architectural sculpture formed from no less than 150,000 individual box plants and accessed by 6 kilometers of meandering pathways.

While other are species present in the garden — notably pine, oak, and cypress which, in their untamed verticality, stand in expressive counterpoint — it is box that reigns supreme at Marqueyssac, cut into myriad walls, balls, boulders, blocks, cones, glacis, towers, and embankments. The contrast between the natural and the artificial, the clipped and the shaggy, the cultivated and the wild is heightened not only by the garden’s stone follies but also by its dramatic setting, which provides vertiginous views over fields, forests, hamlets, villages, and no less than three castles that seem to cling precariously to the steep valley sides. Nearly lost through neglect, Marqueyssac was saved by Kléber Rossillon, who acquired the property in 1996 and spent over a year restoring it. His investment no doubt paid off, for it is now the most visited garden in the region, attracting 200,000 people annually. But how many of them realize they are following in the footsteps of a saint? Giuseppe Sarto, Bishop of Mantua, loved to spend time here meditating on a stone bench placed at one end of the grande allée, where the views are particularly breathtaking. Elected pope in 1903, under the name Pius X, he was canonized in 1954. As another Catholic saint, Thomas More, wrote in his 1516 philosophical investigation of Utopia, “The soul cannot thrive in the absence of a garden. If you don’t want paradise, you’re not human; and if you’re not human, you don’t have a soul.”

Text by Andrew Ayers. Photography by Philippe Jarrigeon.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 20, Spring Summer 2016.