BRAND SUPREMACY: How Supreme Turns Accessories Into Sought After Collectibles

During the peak of racial-justice protests in early June, the graffitied, boarded-up windows of the Supreme store in SoHo, New York’s “premier” shopping district, were breached. According to coverage in the New York Post, protesters entered the skater mecca at 190 Bowery (a converted Beaux-Arts bank building once owned by artist Jay Maisel) through the stockroom, gaining instant access to whatever was left of Supreme’s most recent, pre-lockdown drop. Like rappers doling out free swag at a concert, would-be hype beasts tossed T-shirts into the crowd. In video footage, the frenetic vibe appeared similar to any other Supreme drop — only this time the clothes were free, and no one had to camp out in a police-patrolled line to get their hands on a box logo.

Object Oriented: An Anthology of Supreme Accessories from 1994–2018, by Byron Hawes (powerHouse Books, 2020).

Since 1994, Supreme has created consumer hype from street culture, adorning skate decks, five-panel hats, and hoodies with their now-ubiquitous Barbra Kruger-borrowed logo (I shop, therefore I am, 1990). But it’s not only streetwear that the brand is known for. Over the past 25 years Supreme has sold everything from stickers, tool kits, and money guns to key knives and even blow-up chairs. These subcultural accessories (or objets d’art, depending on your perspective) are consistently bought, resold, and collected, but it’s only recently that almost every piece of Supreme paraphernalia has been catalogued in a new book by skater-adjacent writer and editor Byron Hawes — Object Oriented: An Anthology of Supreme Accessories from 1994–2018.

Supreme lighters and matches are some of the accessories in Yukio Takahashi’s 1,300-piece collection of Supreme design objects auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2019.

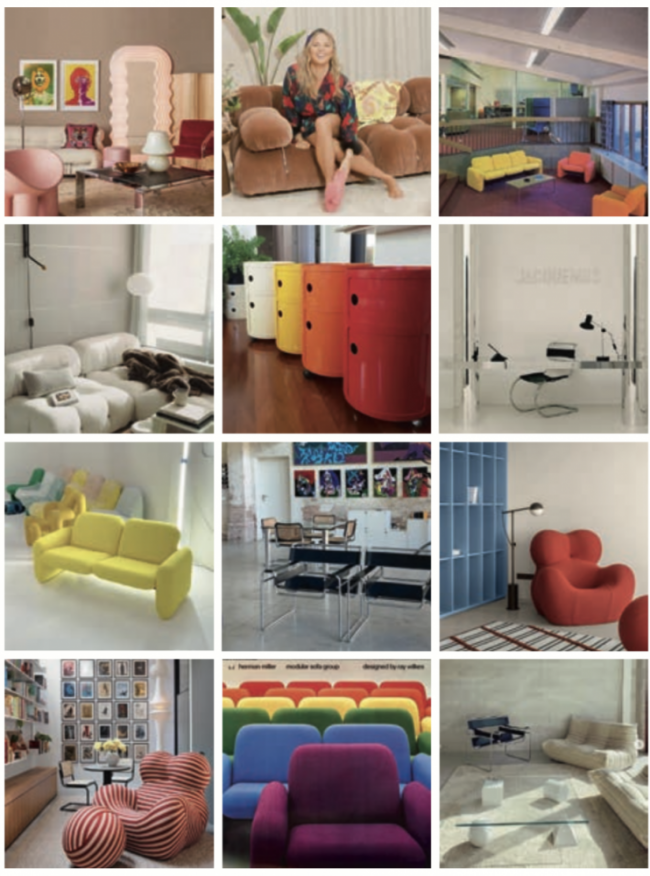

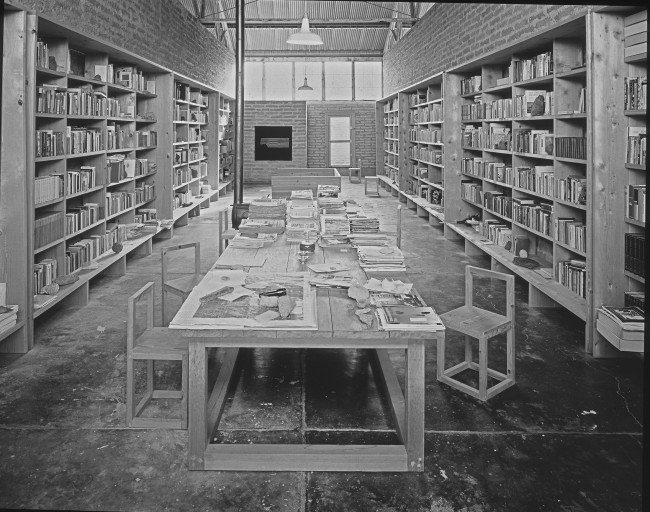

The book is entirely based on collector and professional Supreme reseller Yukio Takahashi’s 1,300-piece collection, which has since been auctioned at Sotheby’s. Takahashi is a dedicated Supreme fan, and sees value in both collecting and utilizing his objects of lust (he uses a Supreme-branded hammer and measuring tape for home improvements). Yet, despite Takahashi’s insight into the Supreme hype-machine, Hawes hardly references him. Instead he utilizes Takahashi’s collection to refute what he sees as a misconception of Supreme accessories as hoardable trinkets, referring to them as part of a pantheon of “design objects” that deserve recognition, like Philippe Starck’s Juicy Salif citrus squeezer, or a chair by Marcel Breuer (though he fails to mention Supreme’s collaboration with Artek in 2017).

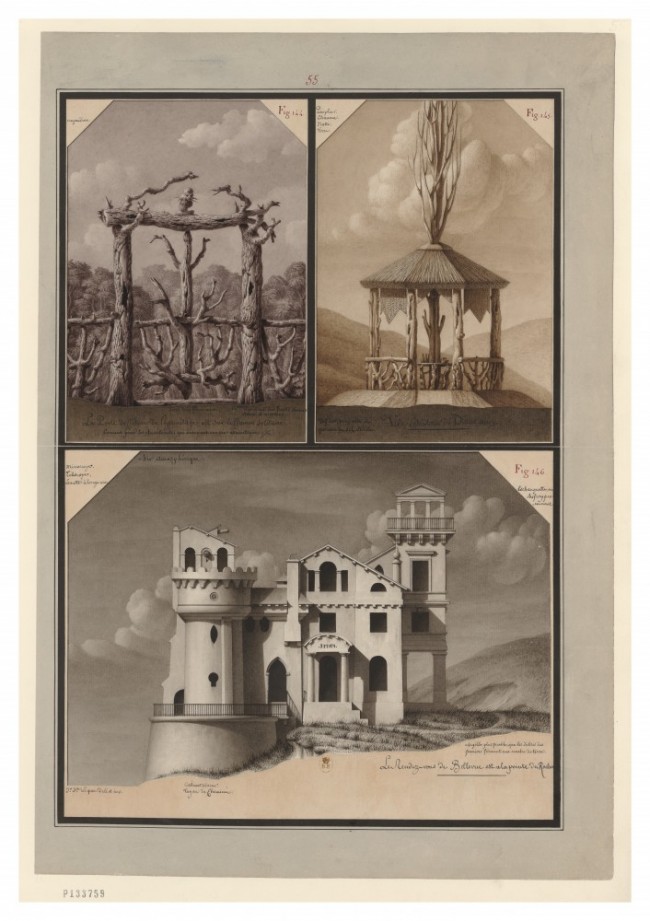

The checkered bench is a 2017 collaboration between Supreme and the Finnish design company Artek. Image courtesy Artek. (Object not included in Yukio Takahashi’s 1,300-piece Supreme collection.) Image courtesy of Artek.

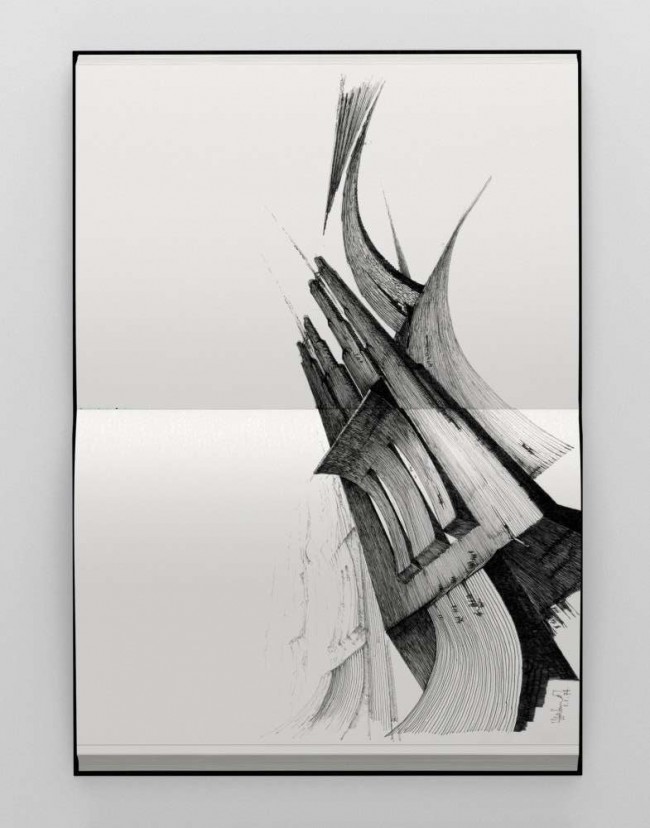

In a AAVE-filled all-caps essay (Hawes is white), the author posits the theory that Supreme’s design output is actually “a highly curated alt-design museum” that celebrates everyday objects, like Kryptonite bike locks, or Maglites, as well as accessories that define the brand’s “outlaw spirit” — like coffin-shaped pocket ashtrays and baseball bats for sports or smashing windows. Yet this sincere interpretation of the company’s intentions seems to miss the point: Supreme’s “outlaw” accessories were not created to institutionalize ashtrays and skate decks in the design oeuvre, but rather to poke fun at the near-religious commodification of everyday objects in late-capitalist culture. Of course, this is obvious when considering Supreme’s infamous 30-dollar branded brick (currently selling on StockX for approximately 200 dollars), but it also extends to the company’s origins as a snobby skate shop with a logo that riffs on another artist’s capitalist critique.

More significant is the way in which U.K.-born Supreme founder James Jebbia was able to harness the energy of the downtown New York skate scene into what many perceive to be a global luxury label, with collaborations ranging from skate decks designed by Damien Hirst to fanny packs created by Kim Jones for Louis Vuitton. It may be ironic to slap a Supreme logo on breathalyzers and handcuffs and see them resold for thousands of dollars on StockX. But when a brand is built on hype from skaters who view Maglites as police batons, not camping gear, one wonders why these items are being produced in the first place, and who exactly they benefit. Skaters may still rock Supreme, but the commodification of disobedience exemplified by the brand’s hard-to-come-by accessories suggests that they’re created for another, more suburban market.

Supreme branded Maglites are marketed at skaters who are likely to see the flashlights as police batons, not camping gear.

In an era of extreme inequality, mass protests, and a global pandemic, many brands are quick to capitalize on doomsday-inspired goods, and Supreme-branded sleeping bags, flasks, and pocket knives set a precedent. Like the go-bags of downtown creatives on six-figure salaries, Supreme’s overpriced accessories provide a superficial feeling of comfort. A backpack full of reflective blankets and astronaut ice cream prepares one for future war or natural disaster in the same way a Supreme-branded rolling tray in a penthouse apartment signals cultural clout for bachelors who don’t smoke. Objects, like religious totems, can offer solace — even when they’re not for us, or we don’t know how to use them.

Supreme coffin ashtray keychain engraved with “See You In Hell.”

In a viral video of the SoHo store looting, protesters are seen ripping graffiti-covered particle boards off of the 19th-century bank-turned-skate shop with bare hands. Later, someone smashes a window with a small hammer. It’s hard to tell whether or not there was a box logo on it, but I doubt there was.

Text by Taylore Scarabelli.

Object Oriented: An Anthology of Supreme Accessories from 1994–2018, by Byron Hawes (powerHouse Books, 2020).

Images from Object Oriented by Byron Hawes, published by powerHouse Books, unless otherwise noted.

A version of this review was originally published in PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.