BOOK CLUB: The Strange Drawn Worlds Of Claude Parent

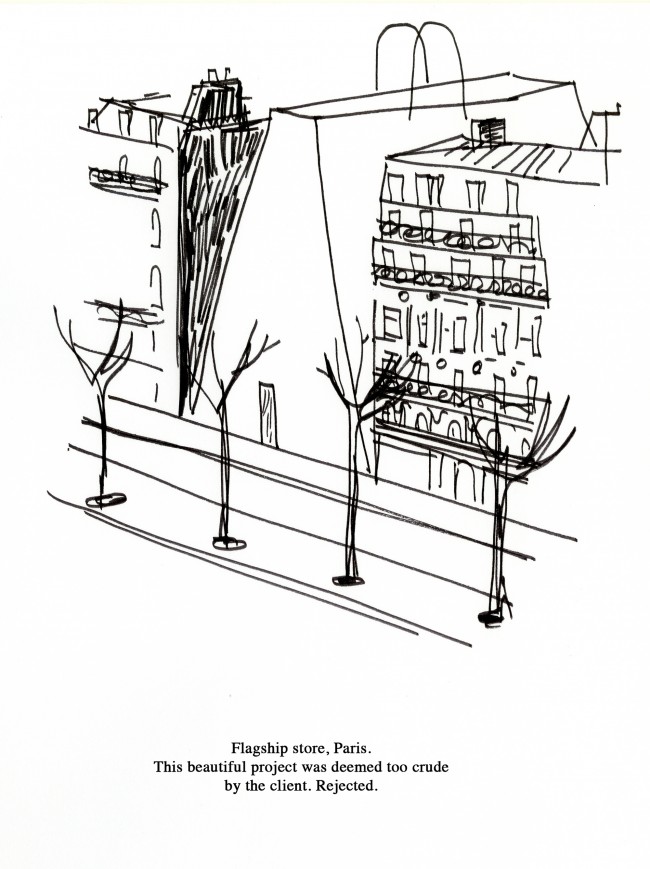

“My imagination is at work for the whole time of a drawing, which can sometimes take two weeks,” wrote the late Claude Parent, famed for the utopian fonction oblique he developed with Paul Virilio in the 60s, a rejection of the comfortable horizontal in favor of the stimulation of life on diagonal planes. “It’s a complex thing, a drawing: it transforms itself and is never as one imagined it to start with. Drawing is an adventure that fascinates and sustains me.” Now, thanks to his daughter and grandson, Chloé and Laszlo Parent, we too can join the adventure, from the nearly horizontal comfort of our very own armchairs: not only does their book Claude Parent: Visionary Architect (Rizzoli, 2019) present a selection of 160 or so of his strikingly graphic images, it also includes commentary from friends, disciples, and admirers such as Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Azzedine Alaïa, and Wolf D. Prix.

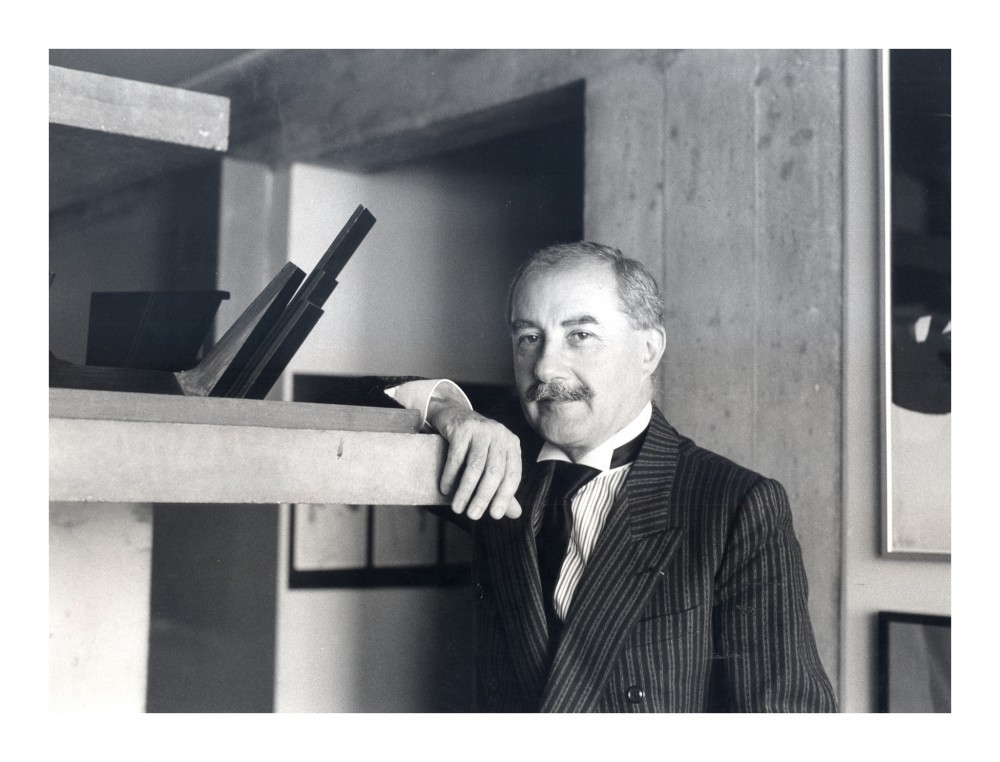

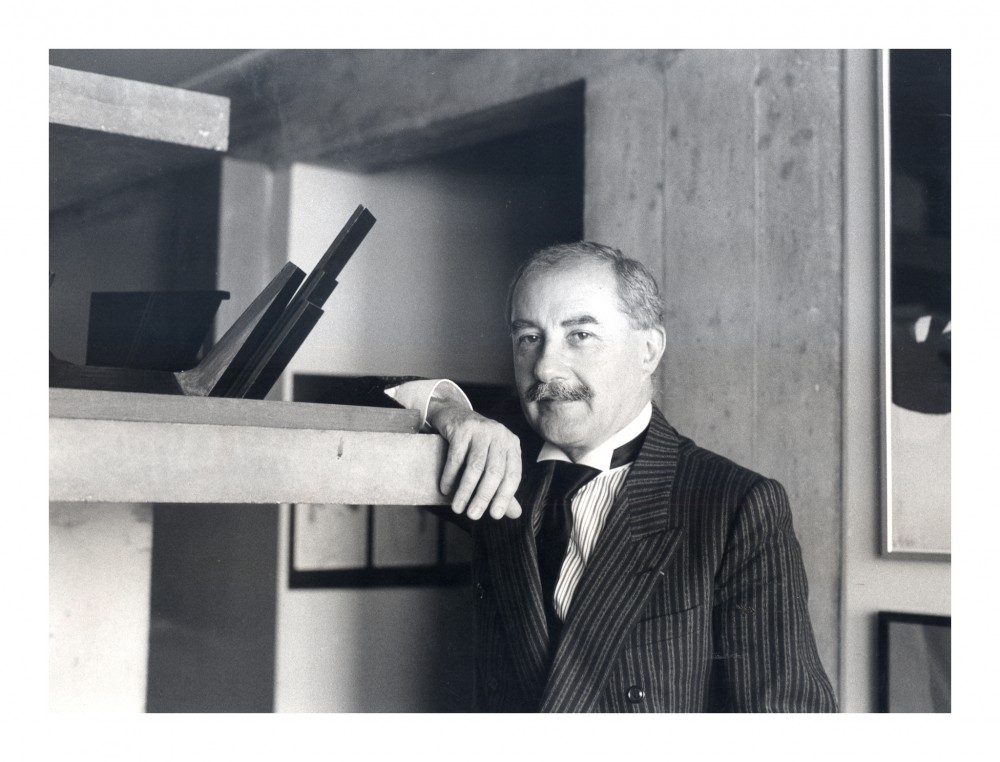

Claude Parent in the 1980s. © Chloe Parent.

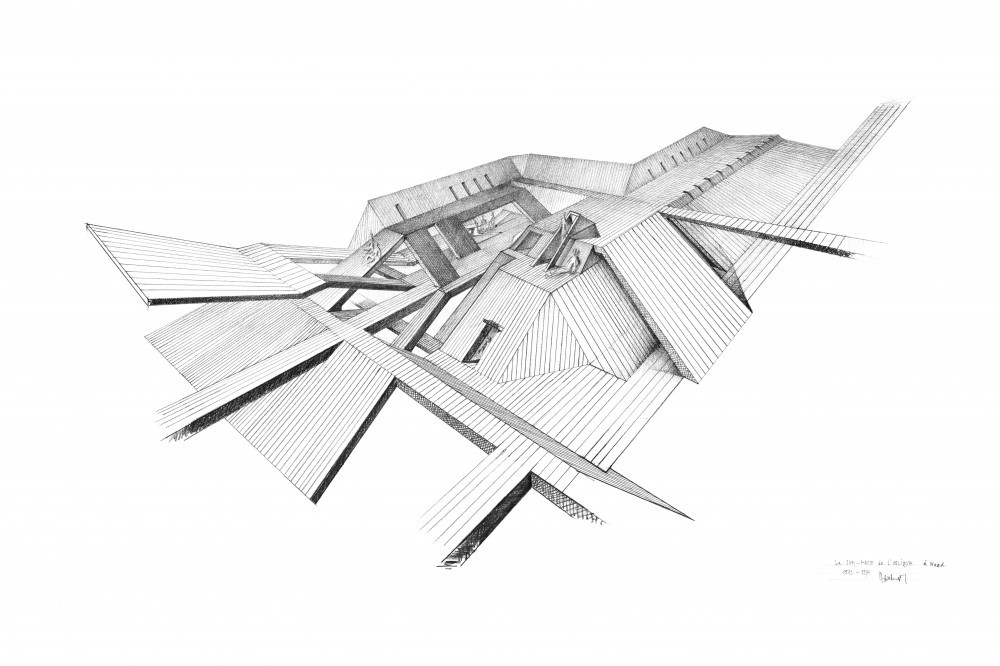

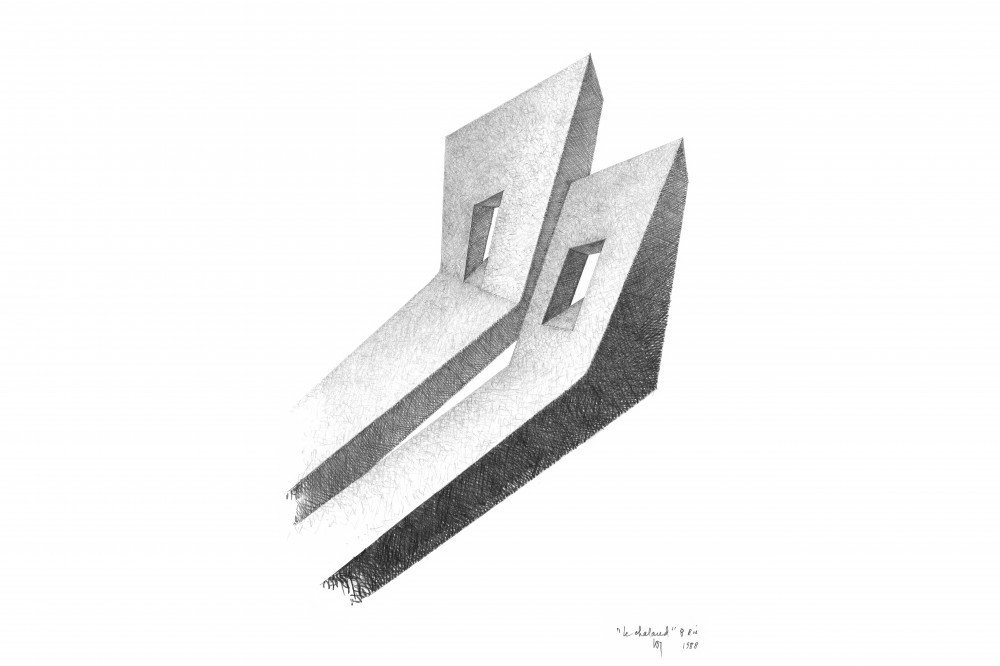

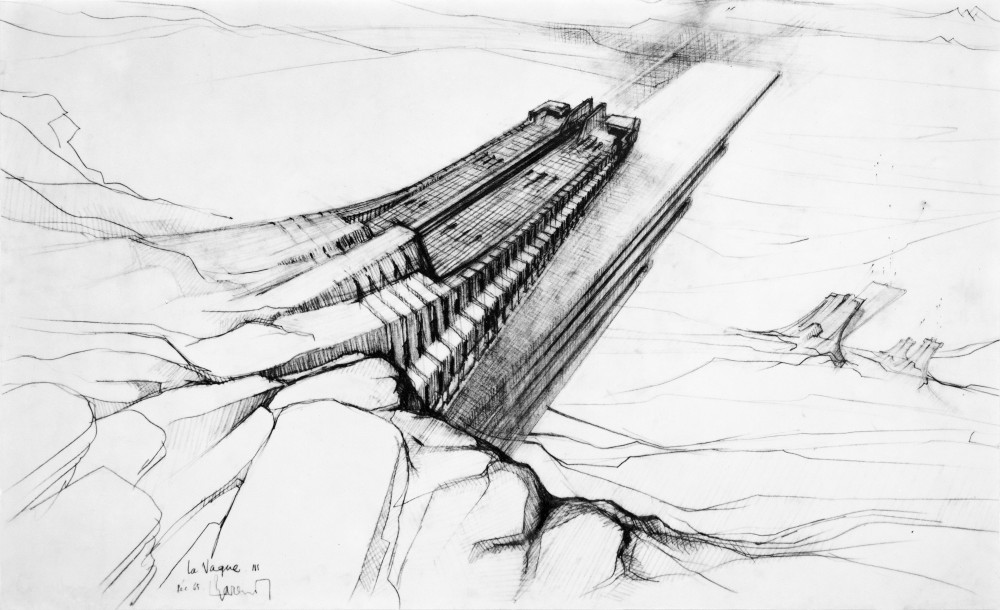

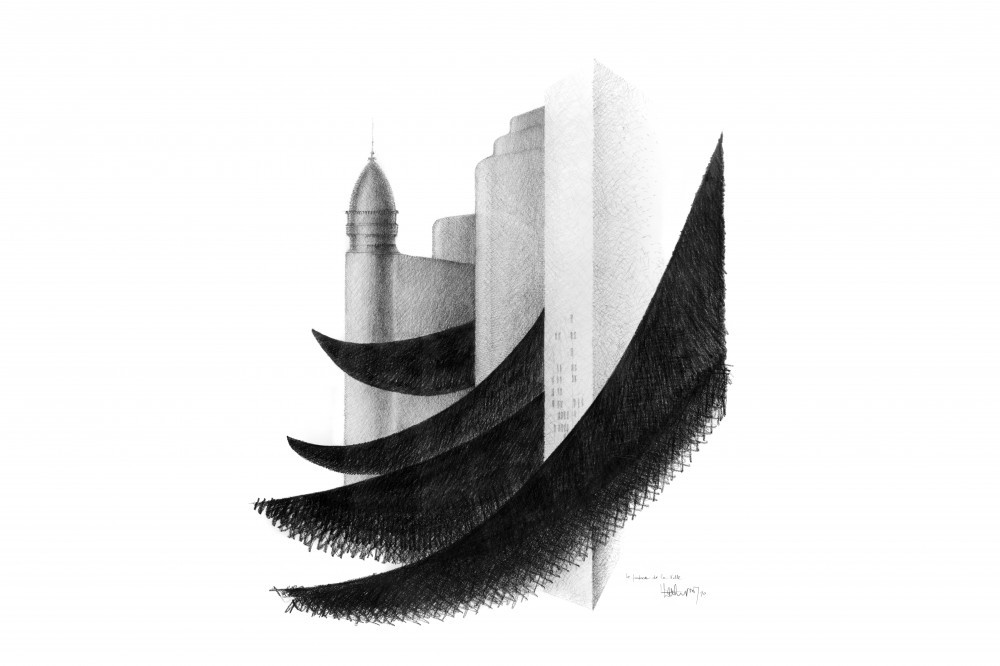

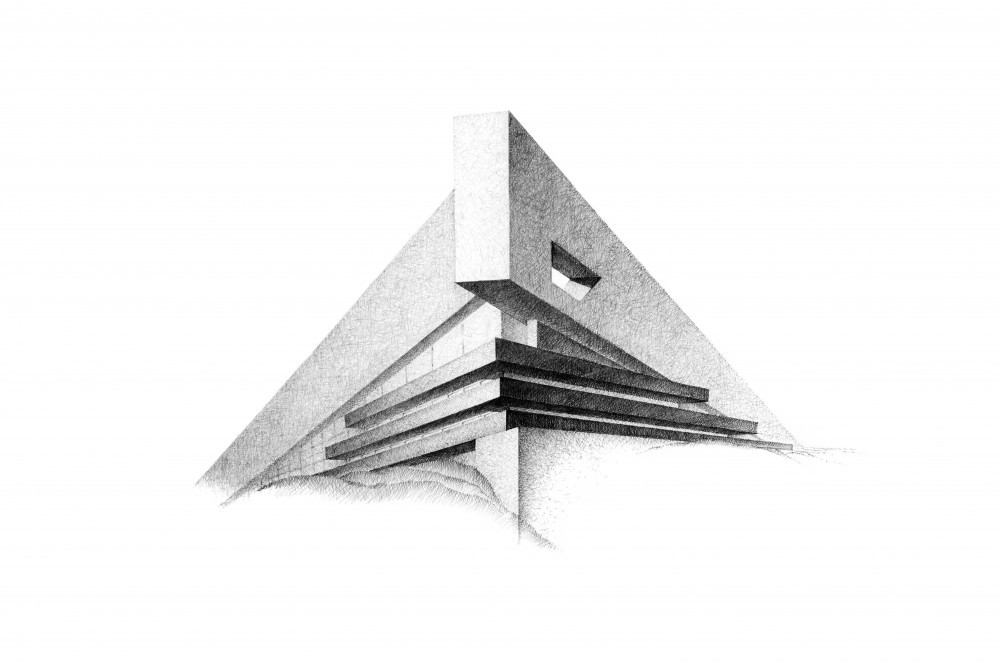

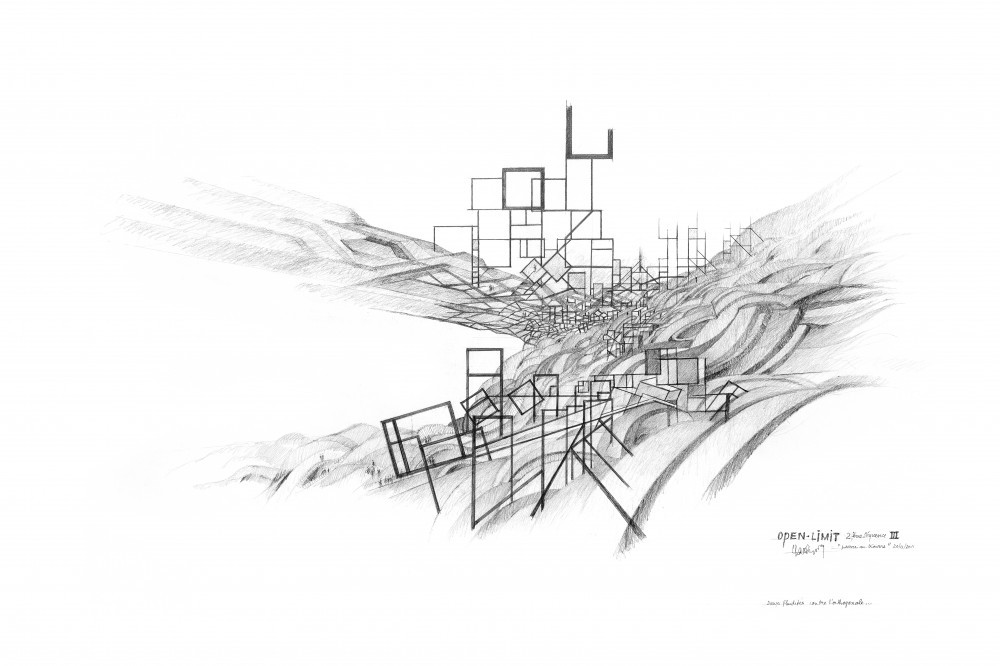

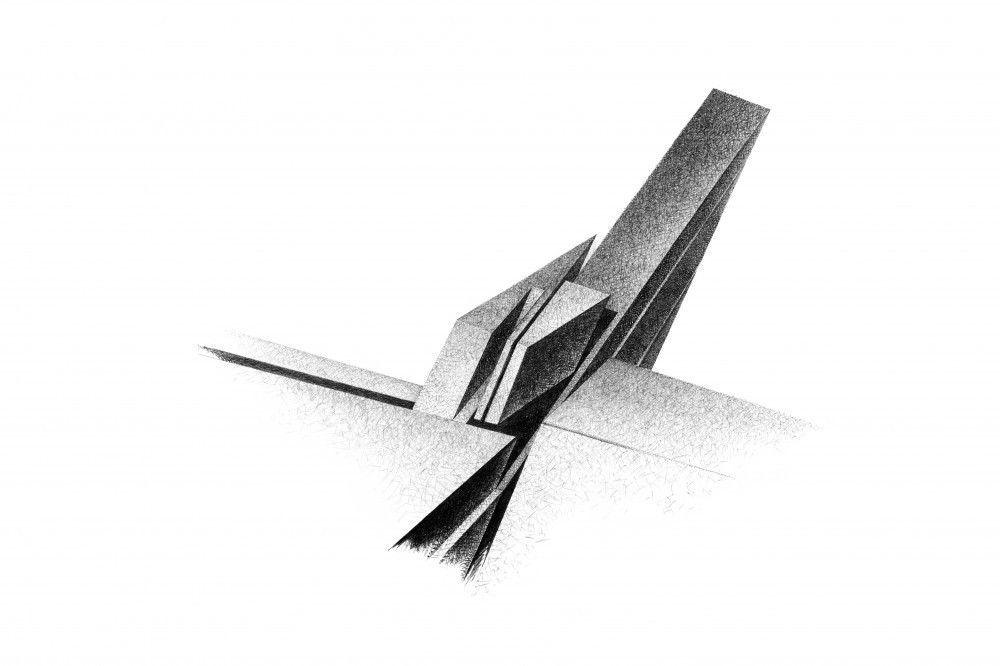

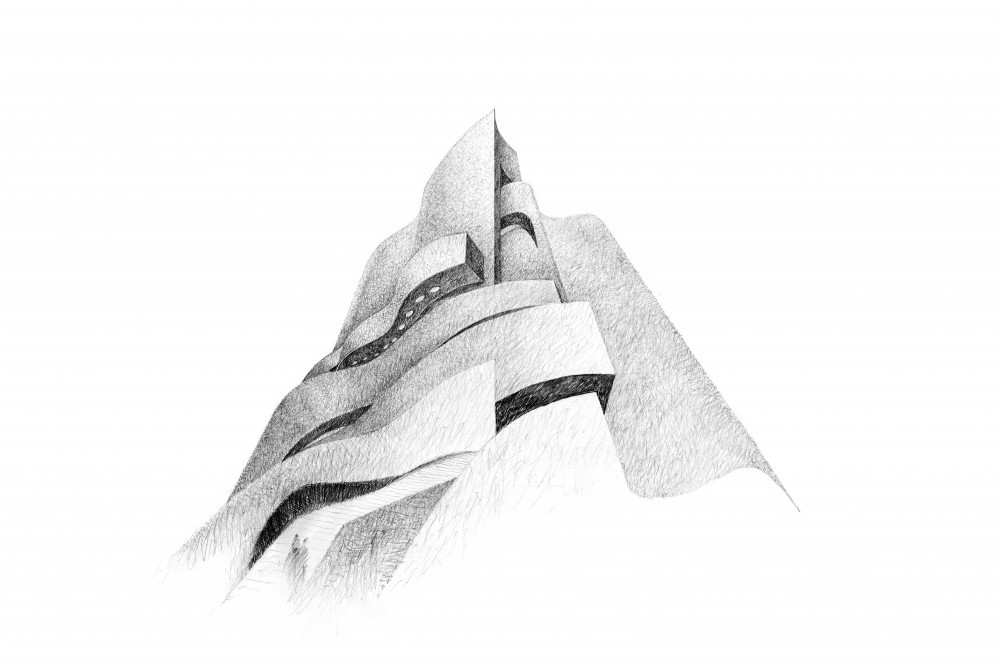

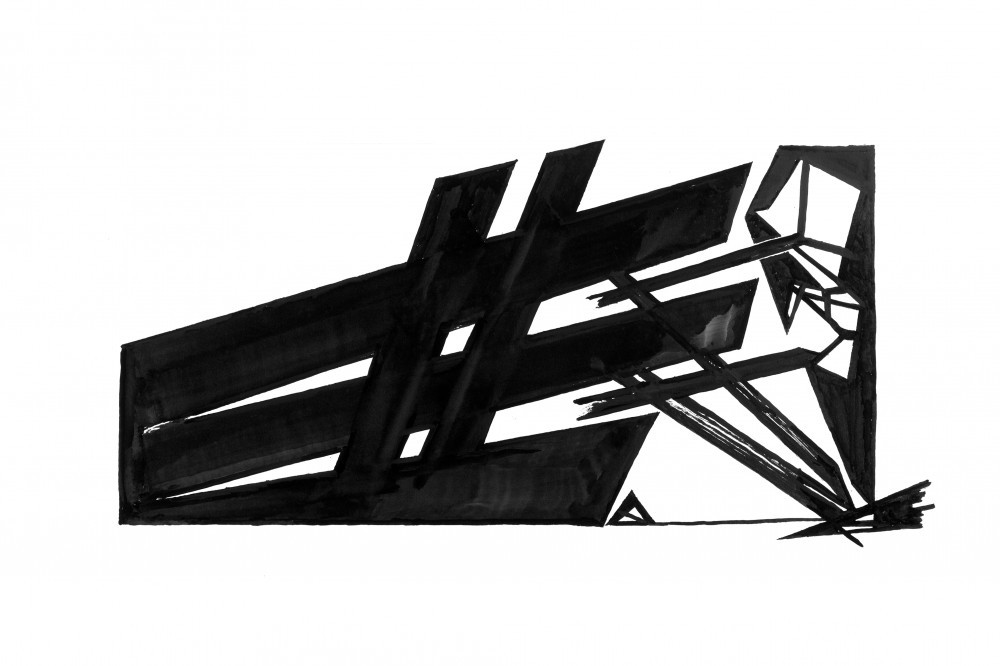

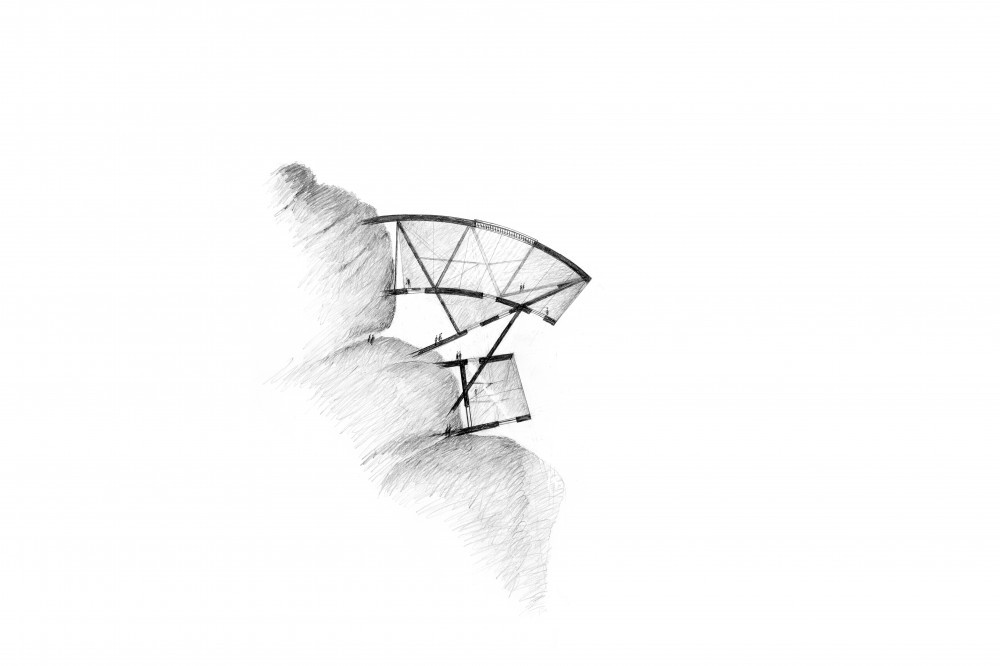

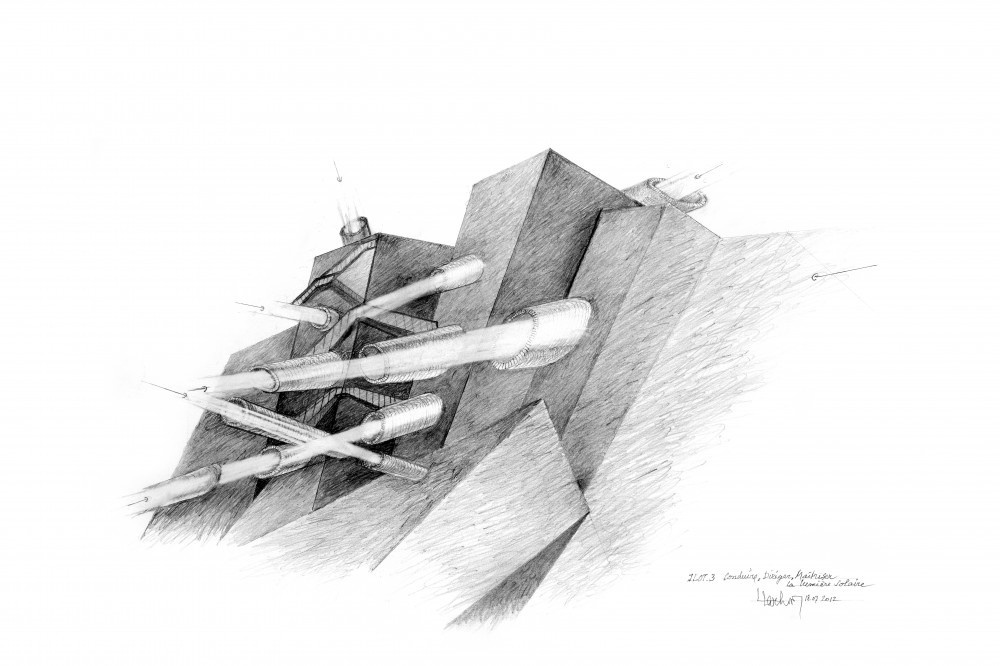

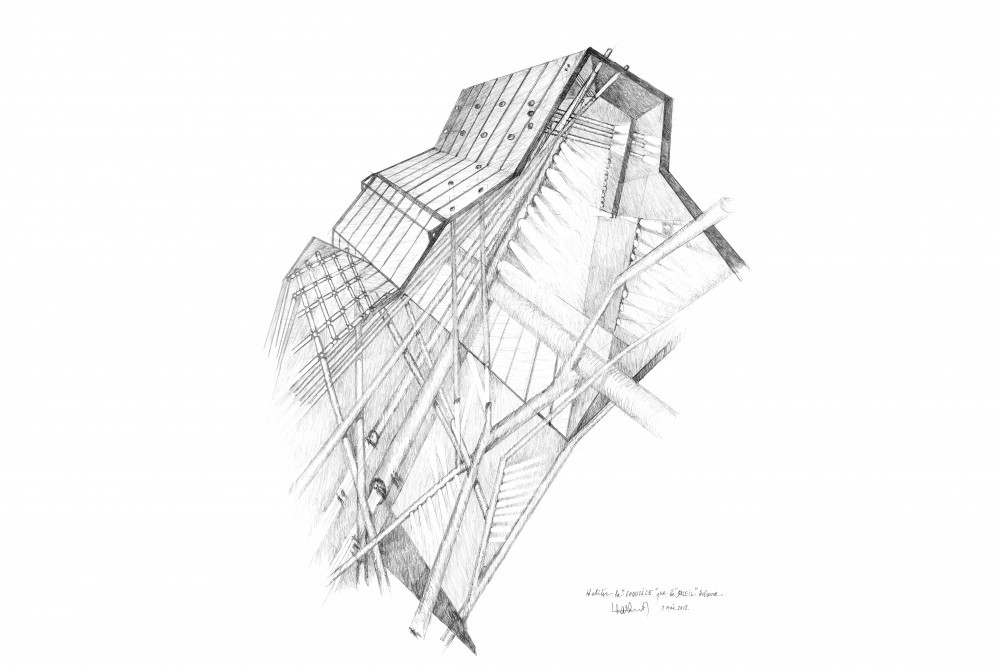

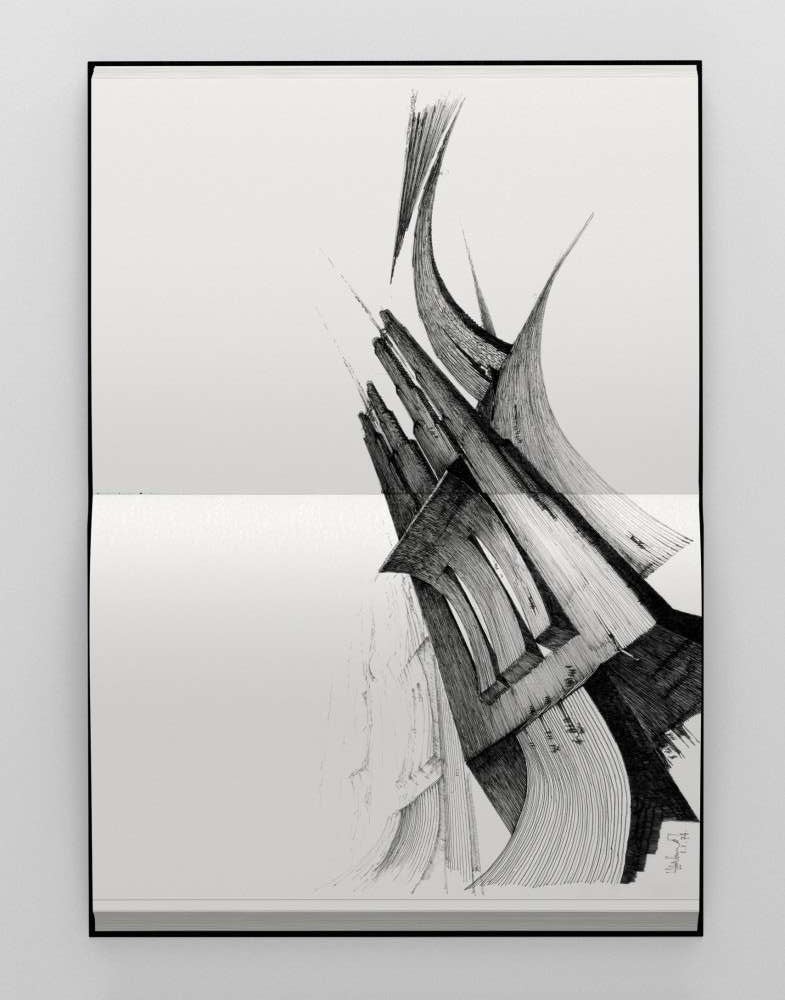

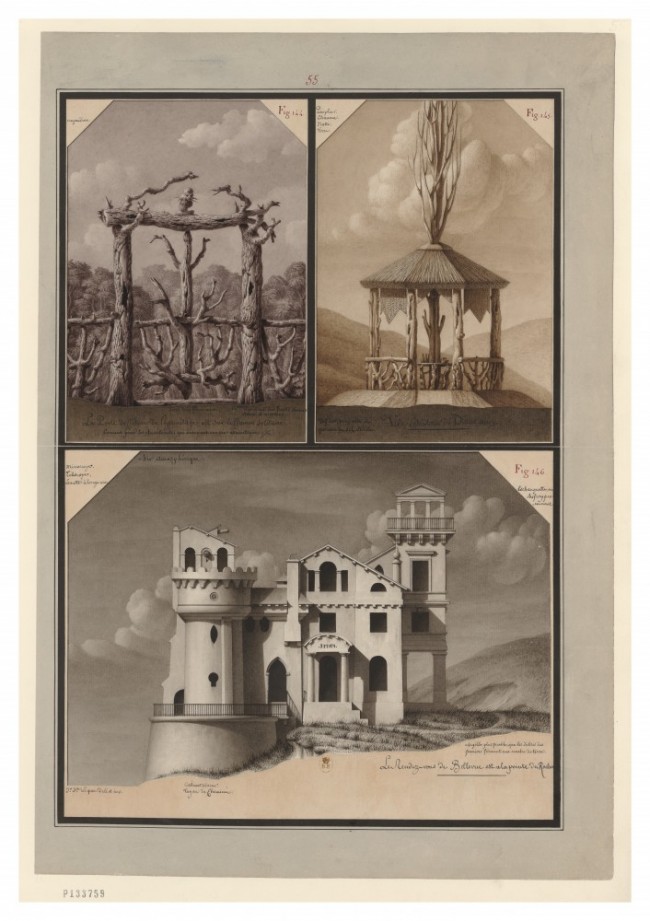

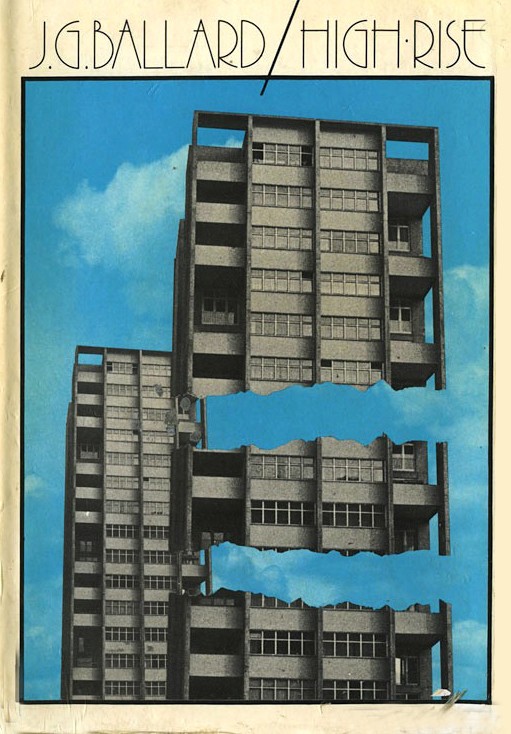

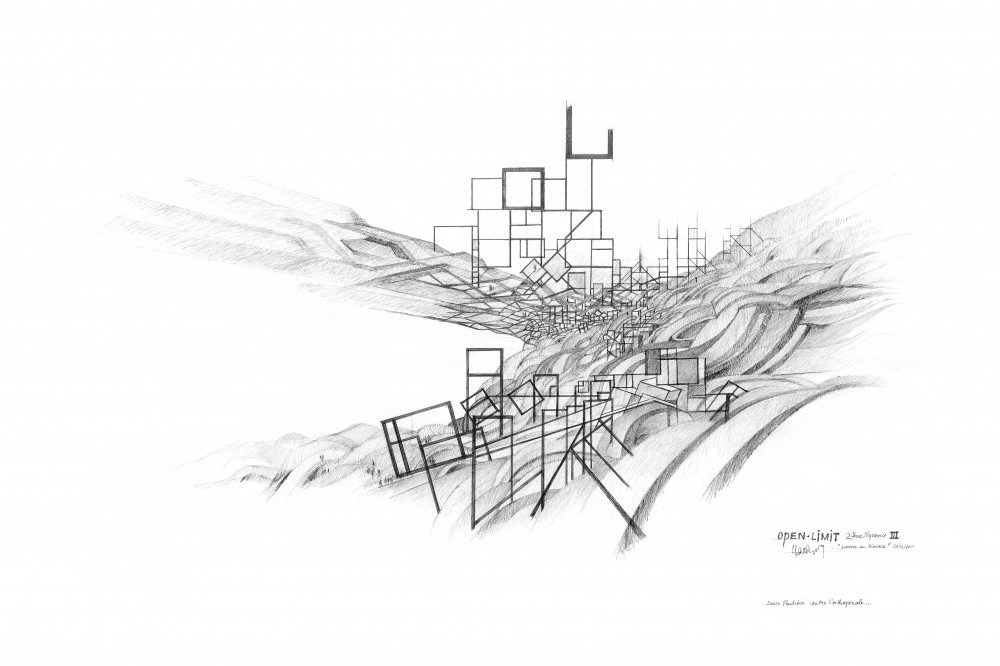

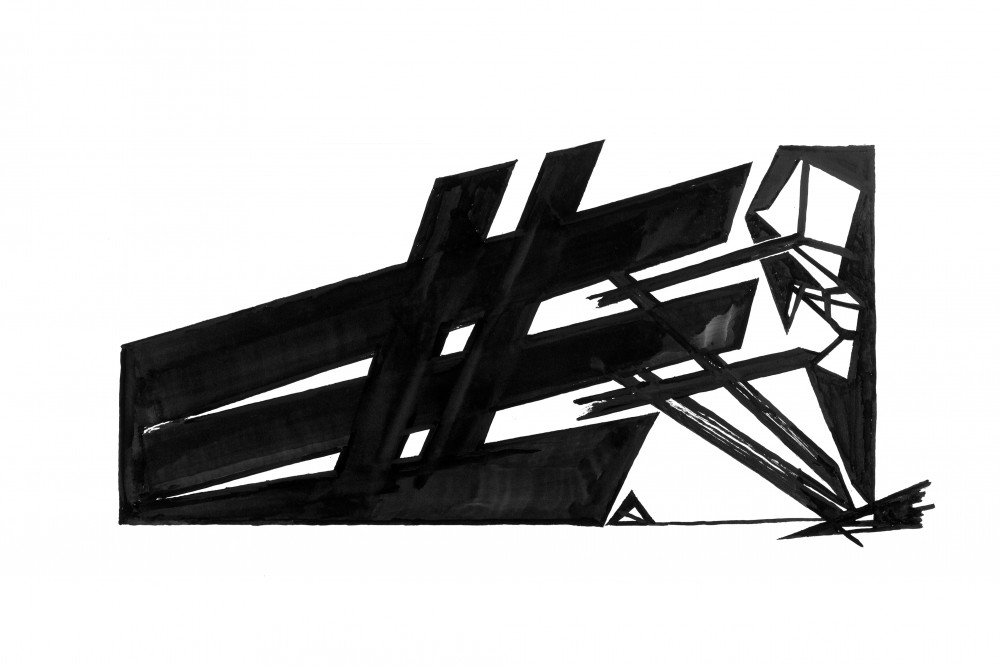

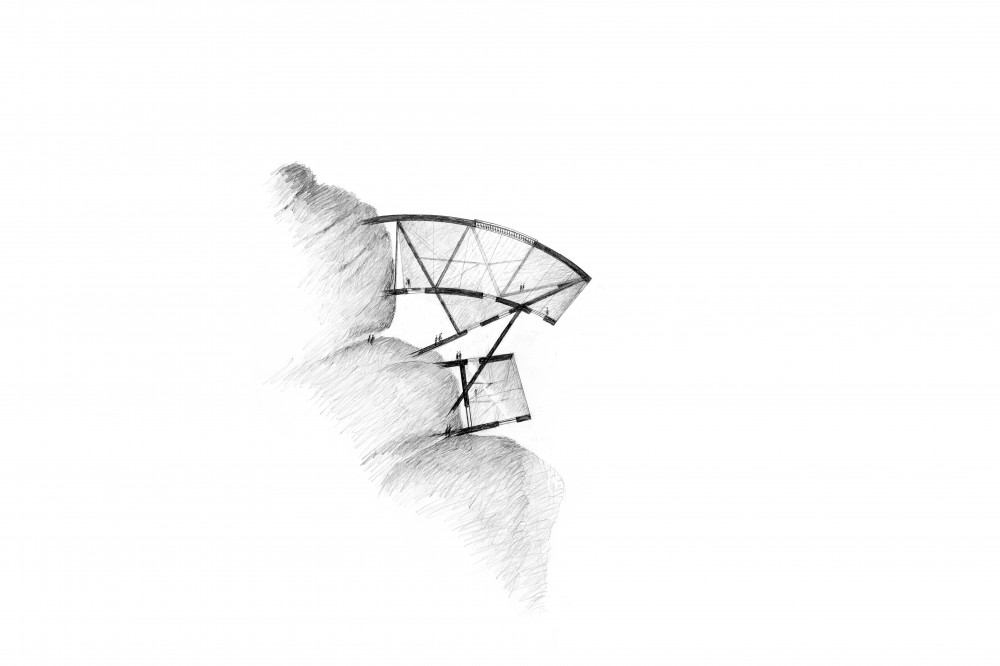

Where most architects use drawing to work out the early stages of a project, record details or scenes that have interested or impressed them, or — rarely these days — for presentation purposes, Parent employed the medium to explore the far reaches of his imagination. Almost always in black and white — he would first use pencil on paper, after which he would sometimes work up drawings into larger-scale pen-and-ink renderings — his images belie the humanism that characterized his writings and built work, presenting scenarios that seem either alienatingly abstract (but hypnotically fascinating in their abstraction) or intimidatingly barren and gigantic. What world is this we see in Turbosite III — un cratère (1966), where ant-like figures scramble over colossal “craters” and inclined cantilevers? What is the desert setting of this over-scaled architecture? Another planet? Our Earth ravaged by apocalypse? Or take Inclisite I — la lame (1966; lame = blade), whose title says it all; or La Vague III (1965), whose sinister “wave” seems to grow from out of desolate rock; or Les grandes oreilles I — les conques (1966), whose fishy forms, seemingly writhing on sand, are straight out of an H.G. Wells horror bestiary.

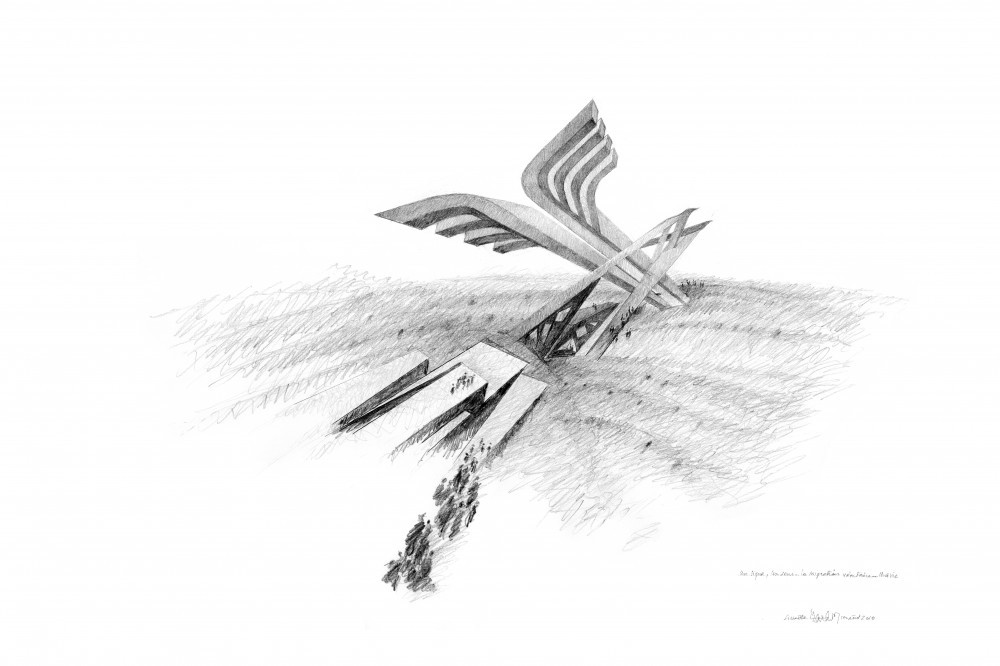

Even Parent’s late drawings, made as a utopian response to the migration crises of the early 21st-century, seem relentlessly bleak. “Let us unfold, on the surface of Planet Earth,” he wrote in the last years of his life, still true to the 60s idealism of the fonction oblique, “huge practicable paths shaped liked continuous ribbons which will ensure the never-ending displacement of humanity on the move.” But, despite the larger-scale, recognizably human figures in a drawing such as La Migration pacifique... (Peaceful Migration, 2010), the vision still appears thrillingly dystopian — in marked contrast to the humorous caricatures that also punctuate the book, and which seem, dare one say it, cheesily cozy in comparison.

While he never stopped drawing, from the moment he could hold a pencil until the day before he died, aged 93, in 2016, it wasn’t until fairly late in life that he began to take his graphic production seriously. It was the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied in the late 1940s, that made him wary of the medium: “in the architecture department,” he later wrote, drawing “was the trap, the lie, the alibi that masked the lack of true creativity… disgust with regard to these practices, to all these tricks, swept through me so hard that, for a long time, I considered drawing dangerous, harmful, and dubious, and systematically destroyed all documents — other than execution plans — that had allowed me to think out a project.” It was, he wrote, only in the 60s, when he began working on the fonction oblique, that he “really took up drawing again, and that a new adventure unfolded by way of this extraordinary medium of the imagination. (Drawings) then became the vehicle for unbridled dreams … (breaking) completely away from reality.”

-

Un signe un sens, 2010.

-

Villa spirales, 2006.

-

Open limit III, 2011.

-

Les Villes Boucliers (2009).

-

Villa bloc b, 2011.

Though he discussed his reasons for drawing, Parent never sought to explain the content of his images — interpretation was the job of the beholder. But perhaps we can get a glimpse into the psychology of his futuristic vision of the sublime from a short poem he wrote in 1990:

When God seems to turn away / Leaving you so alone in the whirlwind of souls / Then dreams / Then utopias / Then creatures of plenitude or nightmare / It depends / Stretch out their hand to you / The hand that draws / To give form to our anxieties / And, were it possible / To exorcise them.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Images courtesy Rizzoli.